5 The Troubled Nineteenth Century

The late eighteenth century reflected a world fractured by constant warfare. France, England, and Spain spent decades in intercontinental conflict over their respective North American colonies; the Seven Years’ War (referred to as the French and Indian War in the American colonies) encompassed battles fought between the First Nations of the Native Americans—and their French and British allies—with the latter envisioning themselves in a battle global domination. The majority of the conflicts were connected to empires using imperialistic practices to expand their coffers and their borders.

The British spent almost three decades attempting to suppress rebellious American colonists through punitive taxes, restrictive laws, and a growing militaristic presence. The British signing of the Treaty of Paris on September 3, 1783, signaled official recognition of the United States’ independence. France found itself in a disastrous state, facing bankruptcy at the close of the Revolutionary War. King Louis XIV exacerbated the financial strain upon the country by levying excessive taxes to fund his extravagant lifestyle. The Third Estate waged war upon the monarchy for the next ten years. The eighteenth century and the French Revolution ended with General Napoléon Bonaparte staging a coup d’état in 1799 and declaring himself First Consul of France.

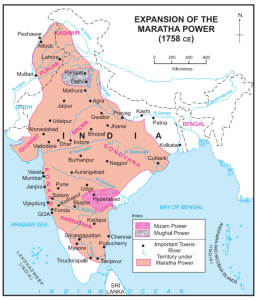

After being engaged in civil wars over leadership succession, Northern and Western India began battling English encroachment. The first of the Anglo-Maratha Wars began in 1775. The British East India Company’s victory at the Battle of Plessy (1757) over the Nawab of Bengal and his French allies became a watershed moment for British imperialism in South Asia. It led to more direct British contestations with Indian empires, including the Maratha Empire. Maratha, a peasant warrior class, was one of the last ruling groups that emerged near the decline of the Timurid Empire (also known as the Mughal Empire), an Islamic dynasty that ruled Northern India. Founded in 1526 by a warrior chieftain named Zahīr ud-Dīn Muhammad, Babur (a name given to him by his Turkic-Mongol populated military) seized power from the sultan of Delhi, Ibrahim Lodhi. Babur was supplied with weapons acquired during trade with the Ottoman and Safavid Empires. Maratha rulers were credited with developing centralized administrative practices. Levying agricultural taxes throughout their territories led to developing finance, trade, and banking networks, as well as a maritime navy on the western coast. Ruling for seven generations, internal battles for succession began weakening the Maratha stronghold. By the mid-1800s, civil warfare had become so disruptive that economic growth slowed.

The East India Company strategically used this turbulent period to their advantage, fighting the Maratha for control of much of early modern India and major parts of northern Pakistan. Subsequent wars were also fought in Burma (now Myanmar, 1824–1826, 1852–1853), Afghanistan (1839–1842, 1878–1880), and Baluchistan in southern Pakistan (1840, 1880, 1917), along with many other smaller wars, leading to the establishment of the British Raj in 1858. For the next 90 years, the British Raj would claim control of modern-day Pakistan, Nepal, India, Bhutan, and Myanmar. The company renegotiated exploitative and punitive terms to their trade agreements in exchange for political and militaristic support to the various warring factions.

By 1749, in attempts to stave off British control, the leading families—Sindhia, Holkar, Bhonsle, and Gaekwar—formed a confederacy to unite against British invasion and conquest. The Maratha Wars (1775–82, 1803–5, 1817–18) were the results of the British East India Company lending militaristic support to the warring factions within the Maratha Empire. The Second Anglo-Maratha War occurred in 1803, and the Third in 1817. By the conclusion of the Third, the British were able to claim victory and fully colonized India.

During this same period, Prussia was battling invasive attempts from Austria—Joseph II intended to reclaim ownership of Bavaria (1778–1789). In 1798, the Society of United Irishmen led an intense, yet brief, uprising against British rule in Ireland.

The eighteenth century witnessed the expansion of several European powers (Britain, France, Spain, and Portugal among them) throughout the western coast of Africa during the origins of the transatlantic slave trade. Enslaving and selling African people, spices, gold, and salt became so integral to the expansion of European empire that a meeting of European heads-of-state drafted an enforceable division of almost the entire African continent during the nineteenth century. During this same timeframe, Northern India was consumed by Britain, while China and Japan battled each other, and Britain, for dominance on the continent of Asia. While German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck’s Berlin Conference (1884–1885) can be considered the formal declaration regulating European domination on the continent of Africa, various European nations had established outposts and settlements almost two centuries prior.

The Portuguese had explored central, eastern, and southern regions in Africa seeking routes for the spice trade. Once Bartolomeu Dias passed the Cape of Good Hope (on South Africa’s Atlantic coastline), the Portuguese began setting up trade agreements and routes. By the 1460s, the Portuguese had feitorias off the coast of Mauritania, Aguin, Kongo, and (present-day) Namibia. For almost a century before the arrival of the French, English, German, and Dutch, the Portuguese monopolized the seaborne trade of gold, salt, and enslaved African peoples. By the mid-1500s, the Kongolese were seeking to terminate the trade agreement, as the Portuguese began to increase their demands for Africans to enslave and sell throughout Brazil and America. However, when the Kingdom of Kongo was under attack, the Portuguese lent military support to the Kongo. In a conciliatory gesture, Luanda Island was given to the Portuguese to colonize. Luanda became a thriving port through which the Portuguese began exporting many Akan to Brazil to work in the gold mines.

By the 1700s, the French were sending hundreds of ships to the coasts of Africa. French ports became epicenters for an immensely lucrative slave trade. Le Havre, Nates, and Bordeaux were way stations that housed the captives taken from Western and Central African regions until they could be transported to Saint-Domingue (formerly Haití), Guadalupé, Martiníque, French Guiana, and (present-day) Louisiana and the Mississippi Delta. By the 1800s, France had established a series of forts and townships along the Sénégal River. In 1854, Napoleon III appointed Louis Léon César Faidherbe governor of the region. He was charged with gaining control of the acacia gum trade and expanding colonial borders. Faidherbe built a port at Dakar and is credited with “modernizing” Sénégal by establishing schools and telegraph lines and building bridges and rail lines. He was able to accomplish this by creating the Senegalese Tirailleurs, an infantry unit used to quash resistance to the French, and indigenous rebellions in the regions. Faidherbe waged war with the Serer (a West African ethnoreligious group) and drafted a treaty with El Hadj Umar Tall that allowed him to gain control of the middle Niger region.

In the 1640s, the Dutch originally set up a small colony in what is now modern-day Ghana to engage in the trade of gold and salt and traffic enslaved Ghanaians. By 1652, the Dutch had moved farther south and established a colony of approximately 90 citizens in South Africa. By 1795, the Dutch population was estimated at almost 17,000. The Dutch used South Africa as the center of their slave-trading business. During the 17th and 18th centuries, the Dutch also invaded Portuguese colonies, while establishing their own colonies in Southern Chile, the Caribbean Islands, Sri Lanka, modern Indonesia, and North America. With the exception of South Africa and Indonesia, Dutch conquests were often short-lived.

In the case of each European colonialist and imperialist power, the objectives of colonialism included securing access to natural resources, establishing military outposts, and utilizing the indigenous population as a source of expendable labor. European empires often fought each other for control of resource-rich regions while seeking to simultaneously conquer the indigenous inhabitants. In each case, various trading companies, with rather benign names, were empowered with military authority to negotiate—or invade—on behalf of their respective mother countries. Entities such as the British East India Company, the French East India Company, the Dutch West India Company, and the Dutch East India Company were given the autonomy to wage acts of aggression on behalf of their monarchies.

The beginnings of the nineteenth century rang in with the false promise of peace—or at least the abatement of invasion.

Liberalism and the Revolutions of 1848

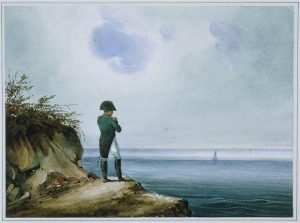

After the defeats of Napoleonic forces in Russia (1812), Leipzig (1813), the Iberian Peninsula (1814), and finally, Waterloo (1815), European monarchists breathed a sigh of relief as they restored the Bourbon dynasty in France. The British, who had led the defense against Napoleon’s final campaign, chose St. Helena in the South Atlantic as a permanent home for the exiled emperor. Napoleon was transported to the island, which was administered by the East India Company, in 1815 and lived there for the rest of his life. He died in 1821, at 51.

At the Congress of Vienna (November 1814 through June 1815), the old ruling families of Europe got together to try to restore what they thought of as peace and order. To a large extent, their priority was trying to restore the status quo ante: the borders that had existed before Napoleon’s conquests and the types of social organization that had prevailed before the French Revolution. The brother of the executed king, Louis XVI, took the French throne as Louis XVIII (the XVIIth Louis had been the dead king’s son, who had died in prison at the age of 10 in 1795); the restored king agreed to return the territories Napoleon had conquered to the empires and nations that had held them previously. As much as possible, the Congress of Vienna tried to turn back the clock and forget that the French Revolution and Napoleon had ever happened while setting up a balance of power to check the possibility of a French imperial resurgence. A European-wide peace would hold until World War One began in 1914.

The empires would even collaborate in the suppression of revolutionary sentiments among their own peoples in the late 1840s. Indeed, although the Russian and Ottoman Empires contested with various European states on their borders to expand their influence in the 19th century, much of the history of 19th-century military conflict in Europe was instead the suppression of revolts, revolutions, and uprisings. These conflicts led to the mass migration of Europeans to the Americas, including Brazil and Argentina, but also Mexico, the United States, and Canada. Furthermore, anti-Jewish pogroms in 19th-century tsarist Russia in the 1820s (Odessa) and 1880s (some 200 or more pogroms across the empire), Eastern European Jews (Ashkenazim) also fled for the Americas.

Questions for Discussion

- Why do you think the trading companies were able to operate with such autonomy on behalf of the Crown?

European Immigration to the United States

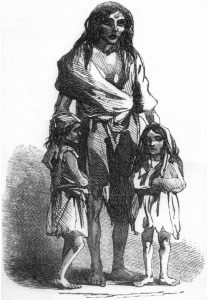

European immigration to the United States during the 19th and early 20th centuries was spurred by a combination of the repression of minority populations and revolutionaries coupled with environmental causes such as widespread famine. The Irish Famine, caused by a blight that rendered potatoes inedible, began in 1845. Potatoes had proved to be an ideal crop for Ireland, and it produced enough of the crop for itself and most of the rest of the British Isles—losing this important food source was disastrous for the Irish peasants. British government aid proved incompetent and ineffective, revealing a scandalous level of prejudice against the Catholic Irish, who, along with Gaelic peoples from Cornwall, the Welsh, and the Scots, were the first colonized peoples of the British Crown. Over a million people in Ireland died because of the Famine, and a million more emigrated to avoid starvation—mostly to the U.S. The population of Ireland, which had been more than 8 million in 1841, never recovered (and is still only about 4.7 million today). Food shortages spread to Scotland and across Central Europe, where the Czech potato harvest was also reduced by half because of the blight.

In addition to rural famines, much of Britain and parts of Europe had begun to industrialize, and poor urban workers were dissatisfied with their wages and living conditions, which will be described below. In 1848, rebels temporarily took control of Vienna and forced the Austro-Hungarian Empire to end serfdom. Southern Italians revolted against the French still occupying their homeland. And a revolution in France ended the monarchy once again and created the Second French Republic. Although revolutionary movements in the German states were unsuccessful in changing their governments, they paved the way for change and resulted in massive German immigration to the U.S.

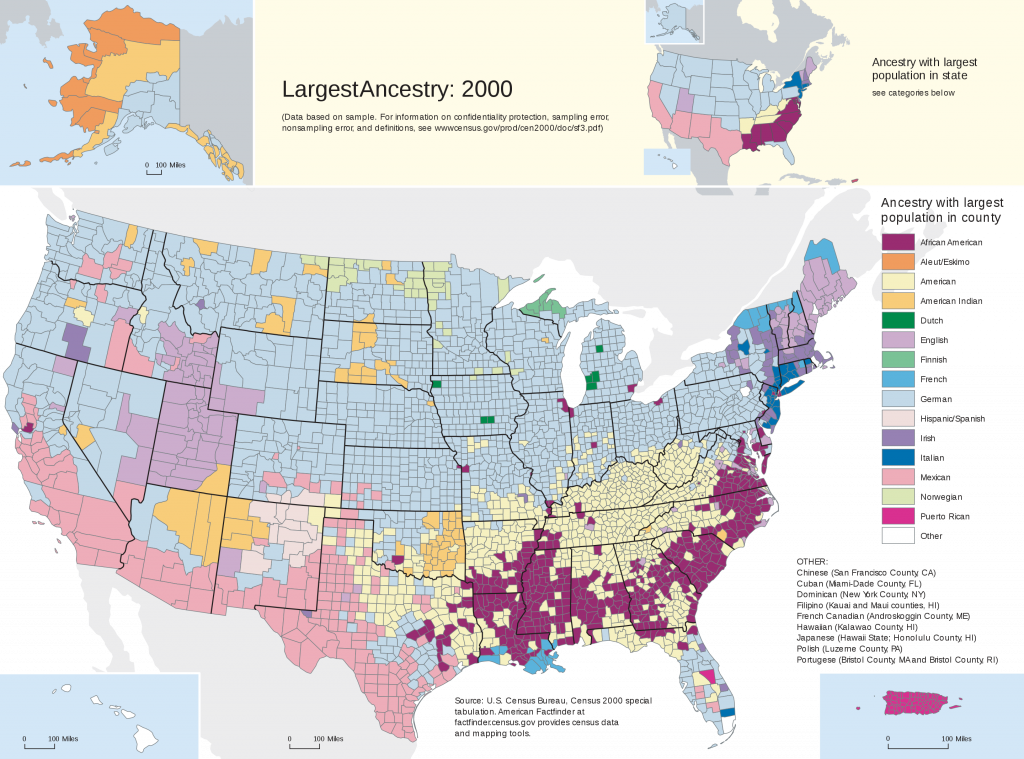

Migration to the U.S. had been slow between the end of the American Revolution and the War of 1812 due to ongoing tensions with Britain and the Napoleonic conflicts in Europe. But beginning in the 1830s and 1840s, immigration from Europe exploded, and the United States became a “safety valve” for the underemployed, politically marginalized, and persecuted of Europe. The Irish in the 1840s were followed by Germans after 1848, who remain the largest single immigrant group. Scandinavians began arriving after the Civil War, but by the 1890s, most new immigrants came from Southern Europe (especially southern Italians—in particular, Sicilians) and from Eastern Europe, including large numbers of persecuted Ashkenazim (Jews) from the Russian Empire and other parts of Eastern Europe.

By the end of the 19th century, the majority of Americans were of German ethnicity. Even today, 46 million Americans are of German descent (light blue on the map). The rest of the top five ancestry groups are Black or African American (38 million, magenta), Mexican (34 million, pink), Irish (33 million, dark purple), and English (24 million, light purple). This population count is complicated by the region in the southeast, stretching from the Appalachian Mountains to northern Texas, where the largest group calls itself “American” and people do not attribute their origin to any foreign nation. These 22 million people are probably mostly of English or Scotch-Irish descent, based on the history of the region. Statewide, the German pluralities range from 11% in Florida to 43% in North Dakota, which explains why the capital is named after Prussian chancellor Otto von Bismarck.

Questions for Discussion

- Why was the U.S. considered a “safety valve” for excess European population?

- Why were some voluntary immigrants welcomed to the U.S. and others excluded from entry?

The Industrial Revolution

Social changes in the 19th century were the direct result of the Industrial Revolution fueling the desire for the expansion of empire. Empires that were industrializing were not limited to Europe and the United States but also included Mexico, Brazil, and Japan. Yet industrialization was a catalyst for imperialist sentiments in the United States as well as in Europe, whose imperialist ambitions then had a direct impact on the rest of the world, as we will discuss in the following chapters of this book. So before we look at the rest of the world, let’s look more closely at industrialization.

The last two hundred years of human history are also the story of the Industrial Revolution, imperialism, colonialization, and its effects. The life of an agricultural worker living in France, Mexico, China, India, or Ethiopia in 1100 CE was not that different from that of a similar peasant living in the same place 200 years earlier or later. But because of technology, industrialization, and urbanization, today’s world is considerably different today than it was 200 years ago. In fact, the change has accelerated: we live much differently than our parents did when they were our age. Consider how many of you may be reading this on a handheld electronic device, which was not all that common even ten years ago. The acceleration of life in many aspects is just one of the results of the unprecedented worldwide technological innovations of the last two centuries.

Even today, there are five necessary inputs that are required for industrialization: capital, technology, an energy source, availability of labor, and consumers. By the late 1700s, Great Britain had all of these and is typically viewed as the birthplace of the Industrial Revolution. The story goes that continental Europe and the United States soon followed. Yet this view completely ignores that industrialization required the capital—including raw materials and finances together—of locations around the world. Thus, more contemporary views see the era of industrialization as a global process that began simultaneously in British colonies and Great Britain while also arguing that proto-industrialization had already occurred in Mughal India.

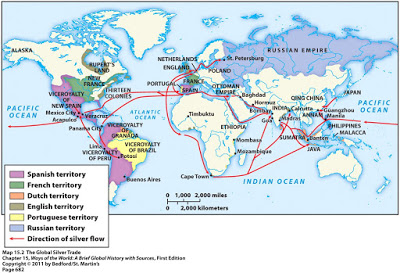

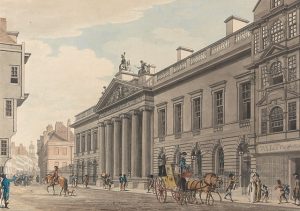

But why Great Britain? Capital—being a financial or other type of productive input in manufacturing processes—was available to merchants and others who benefitted from world trade. The British dominated the slave trade (the British source of free and exploited labor) and the corresponding cultivation of sugar during the 18th century, and those involved in the trade accumulated great wealth. Furthermore, the East India Company was also a source of capital through their trade with South Asia in tea and textiles. During the 1680s, trade with the Mughal Empire in India, and later the transatlantic slave trade, allowed the officers in the East India Company to enjoy unprecedented prosperity. The company set up trade agreements in India, the Persian Gulf region, and China to traffic spices, silk, indigo, saltpeter, tea, and African captives. By the 1800s, the company, fearful of profit loss, propagated an illegal triangular opium trade with India and China, which maintained the accumulation of wealth.

This wealth combined with the acquisition of large swaths of land, which led to political power. This power allowed the company’s officers to lobby Parliament to deregulate trade with India in 1694. The profits amassed allowed the trading company to become instrumental in the passage of laws. It served as a military presence, negotiated treaties on behalf of England, built towns, and enforced colonial law. The company’s establishment of a college and military seminary reflected the company’s influence in British politics. Students at the East India College were educated solely to work within the company, and students in the seminary were trained to serve at the military installations in India.

These factors contributed to the company becoming the foundational model for a successful joint-stock company, in which individual investors purchased shares, which spread ownership and limited financial liability, allowing for greater risk taking. Soon, factories would be following the same joint-stock model in order to accumulate the necessary capital for investment.

Gradually, capital became an economic category that was financialized. The term “capital” itself changed in connotation. It referred less and less to raw materials, while it increasingly referred to simply having a massive amount of money. “Capitalists” were people who had so much money that they could make more money without any labor at all. Capitalists made money simply through investment in profitable manufacturing models: i.e., those that made use of the greatest possible exploitation of labor.

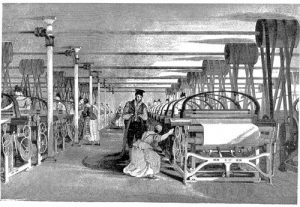

Capitalists were also the financiers of inventors. New technology also made mass production possible, which first occurred in the British textile industry. The spinning jenny and power looms increased the efficiency of spinning wool and cotton and then weaving the thread and yarn into cloth. From this beginning, inventors began seeing the possibilities of mechanical production in other areas such as processed foods, clothing, paper, and household items. Even today, countries usually begin on the path to industrialization through the textile and processed food industries.

Great Britain also had abundant energy sources to power the machines. Like flour mills, textile mills initially used the power of rivers to spin water wheels and turbines connected to spinning and weaving machines. Later, the development of an efficient coal-fired steam engine by Scottish engineer James Watt made it possible to locate factories closer to cities, transportation hubs, workers, and consumers. Both water and coal are still important sources of energy throughout the world. Agricultural improvements in the previous century and the introduction of new staple crops like the potato, imported from the Americas, produced more food using less labor. Improved nutrition allowed Britain’s population to grow, increasing the number of people available for work in the factories. With a larger population involved in a wage economy, producing goods for others and not for themselves, Great Britain also created consumers for the textiles, foods, and other products manufactured in new factories. Soon, British merchants were selling industrial products to Continental Europe and to an increasingly important market of consumers in Britain’s colonies. The ability to sell manufactured goods to a “captive” colonial market added to the rush for overseas empires by the European powers, the United States, and Japan in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Every European empire wanted consumers for the products of the “home country” and wanted to lock up the valuable natural resources needed by the industries of the empire.

Questions for Discussion

- Are there connections between the acquisition of capital, the emergence of the Industrial Revolution, and the transatlantic slave trade?

The Industrial Revolution saw a gradual transition from handicrafts made in the home or in small shops to manufactures produced in factories, which in itself caused social and economic disruption—and improvement—among ordinary workers and their families. In early America, for example, a regular part of women’s work was spinning thread and yarn from wool, flax, or cotton at home, then weaving cloth and making “homespun” clothing for their families. This was hard, slow work and took up a lot of women’s time. As soon as they were able to buy cloth from textile mills, women took advantage of the opportunity to devote much more of their time to other tasks around the farmstead. Often, they began market gardening or keeping an extra cow and churning butter to earn “pin money.”

Pins and other similar products were examples of manufactured products. These goods were usually supplied by peddlers who traveled by foot. Pins and other such necessities were usually supplied by peddlers who walked across the countryside in the days before easy access to general stores that sold dry goods.

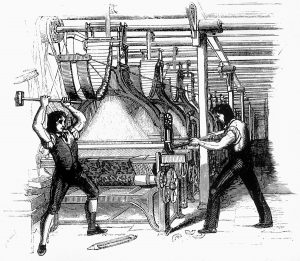

The other side of handicraft manufacture, though, was the type of work done by the Huguenot weavers—descendants of refugee French Protestants—in East London. This was a whole community of people who specialized in weaving using tools and techniques that were available before the advent of large-scale textile mills. They were put out of business by the more efficient manufacturing systems that went along with the new technology, but they did not give up without a fight. Many became “Luddites,” part of a movement of handicraft workers that secretly entered factories and destroyed machinery, blaming the fictional “Ned Ludd” for the acts of sabotage (“Ludd” refers to the wooden clogs workers wore in France, which they would throw into the machinery to break it). Governments were quick to crack down on Luddite labor organizers—a couple of executions quickly took the wind out of their sails.

Industrialization was possible because farms were producing high yields in the early 19th century, creating both an available workforce and a consumer market for many of the products of early industry. In addition, nations like Britain with colonies had another lucrative market for manufactures. Even after the American Revolution and the War of 1812, the United States remained a supplier of raw materials like grain, timber, cotton, and salted pork to the former “home country.” In return, Britain shipped its manufactured goods to ports like New York, where they were carried inland on the Erie Canal, and New Orleans, where they made their way up the Mississippi River to the interior. Britain also cultivated trade relationships with other new nations like those of Latin America. British representatives like the envoy sent to Simón Bolívar’s Congress of the Americas worked hard to convince the new nations to ship raw materials to Britain in exchange for industrial goods instead of developing their own industries. However, they were not universally successful, as industrialization in Brazil began in the 1860s as a result of surges in demand stemming from the American Civil War and the Paraguayan War. Indeed, the expansion of industry in Brazil from the 1870s onward was a constant. Industrialization in Mexico began even earlier, in the 1830s. Yet the British efforts were largely successful in Colombia, where industrialization would not take off until after World War I.

Questions for Discussion

- Why might “Luddites” or others oppose industrialization?

- What were the advantages of industrial production?

![By John Kay - This file was derived from: AdamSmith1790.jpg, which is from Library of Congress[1], Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=4680616 Side view of Adam Smith in three-cornered hat, long coat, and buckled shoes standing at table with cane in hand](https://louis.pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/sites/18/2022/05/727px-AdamSmith1790b-202x300.jpg)

The role of governments in industrialization should not be overlooked. Governments and monarchies sanctioned the roles of privately owned companies in negotiating trade agreements, scouting regions to settle colonies in possession of the raw resources, and influencing legislation.

Official British trade missions argued the benefits of “free trade” now that Britain’s manufacturers had gained the advantage in producing low-cost goods. But the devotion to free markets championed by Adam Smith and his disciples was newfound. When inexpensive cotton calicoes from India in the 1720s had begun to be preferred for making English clothing, the domestic wool industry had pressured Parliament into passing the Calico Acts to prohibit their import. But later, when the British textile industry began using technology that gave Britain an advantage in cotton cloth production, the government did not consider the complaints of the East London weavers and even took steps to protect trade secrets and prevent too rapid a technology transfer to help British industry profit on its innovations. Britain began producing cotton cloth even more inexpensively than India—and suddenly, the British began preaching about “free trade” and pushing to erase any tariffs or regulations that might prevent British textiles from dominating world markets.

The governments of Continental Europe and the United States quickly tired of simply being a source of raw materials for British factories and a market for British goods. To support economic development, these governments began taxing imports with tariffs to protect emerging industries from a flood of British-manufactured goods. Tariffs increased the price of imports to consumers, encouraging them to buy the now competitive domestically produced goods. Protection from foreign competition has helped many fledgling industries get off the ground in developing nations. However, if industries remain protected, they may have less incentive to become internationally competitive in price or quality. Governments that choose to constantly raise tariffs run the risk of subsidizing their industries’ inefficiencies and reducing the welfare of their consumers as industrial improvements in other countries lower the price of imported products.

You can view Every Year of Indian Colonialism by clicking this link: https://youtu.be/yD0dt_f8DIc or by watching the embedded video below:

Transportation, Steam Power, and Interchangeable Parts

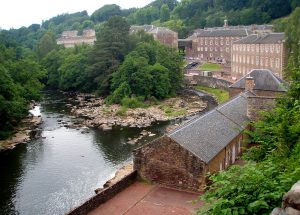

Most histories begin the Industrial Revolution with steam engines and many mention that by the 1820s, steam-powered looms had displaced the hand weavers in the cotton industry. This description actually misses a whole generation of innovation and growth when textile mills were powered by water. The Scottish textile factories of New Lanark, for example, were begun in 1786 by David Dale using water-power technology developed by Richard Arkwright in the 1770s. New Lanark was built on the Clyde River in Scotland, and all of its machines were powered by the river until the mills closed in 1968. The American textile mills in New England that dominated the world market in the second half of the 19th century also used water power. The men who started the Boston Manufacturing Company, which built the cities of Lowell and Lawrence in Massachusetts to take advantage of the water power of the Merrimack River, visited New Lanark in 1811 to learn the technology before they began their venture.

Robert Owen and his partners had bought the mills in 1799 from David Dale, Owen’s father-in-law. Sensitive to the negative social changes that industrial growth had brought to other parts of Britain, Owen built schools for the children of his workers and social organizations for the families. He put an end to the long-standing custom of forcing workers to buy only from the company store and tried to make New Lanark a real, living town. Owen’s partners had objected to his philanthropy, claiming that healthy, happy, well-educated workers did not really boost the bottom line. Rather than fight with them, Owen simply bought his partners out.

Questions for Discussion

- What are the pros and cons of tariffs?

- Why would an industrialist like Robert Owen be concerned about his workers’ social welfare?

The initial expansion of transportation networks for mass-production industries was also water based. In industrializing countries, canal building became a craze from the 1820s through the 1840s. Many local canals connected newly established towns and villages to markets all over the United States, Great Britain, and Continental Europe. The Erie Canal in New York State, for instance, connected Buffalo, on Lake Erie, to Albany, where the canal met the Hudson River, navigable all the way to New York City. Over 350 miles (580 kilometers) long when completed in 1825, the Erie Canal included thirty-six locks to ease barges down a gradual decline of more than 550 feet (170 meters). As agricultural goods shipped down the canal eventually made their way to markets in industrializing East Coast cities, pioneers established farms all along the canal, and the Erie Canal was key to the western settlement and expansion of the United States, especially before 1865. Canal laborers were frequently Irish immigrants who often settled nearby once the canal was built.

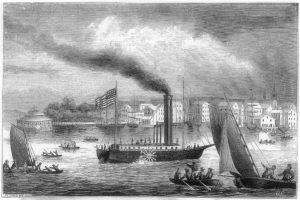

Steam power soon became extremely important to transportation as well. Until steam engines were put on riverboats, shipping had depended on either wind and river currents or human and animal power on canal towpaths. Goods could easily be floated south from farms on America’s rivers, for example, but it was much more difficult and expensive to ship products against the currents to the frontier. Flatboats and rafts accumulated at downstream ports such as New Orleans and were often broken down and burned as firewood. Steam engines made it possible to sail upstream as easily and quickly as down, causing an explosion of travel and shipping that radically changed frontier life. Oceangoing steamships made travel and shipping quicker and safer and allowed travelers and merchants to keep to regular schedules.

Steam engines were a product of early European industrialism. The first steam patent was granted to a Spanish inventor named Jerónimo Beaumont in 1606, whose engine drove a pump used to drain mines. The French scientist Papin built his steam piston in 1630 after visiting the Royal Society in London, and Englishman James Watt’s 1781 engine was the first to produce rotary power that could be adapted to drive mills, wheels, and propellers. Robert Fulton, an American inventor who had previously patented a canal-dredging machine, visited Paris and caught steam fever. Fulton sailed an experimental steamboat model on the Seine and then returned home and launched the first commercial American steamboat on the Hudson River in 1807. The Clermont was able to sail upriver 150 miles from New York City to Albany in 32 hours. In 1811, Fulton built the New Orleans in Pittsburgh and began regular steamboat service on the Mississippi.

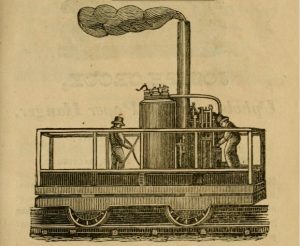

The other transportation technology enabled by steam power, of course, was the railroad, which was even more revolutionary than the steamboat. In spite of their power and speed, steam-powered riverboats depended on rivers or occasionally on canals to run, but a railroad could be built almost anywhere. Suddenly, the expansion of commerce was no longer limited by the routes nature had provided into the frontier.

Small railroads using horses were already common in mining operations in Great Britain and Europe before the advent of steam power. The first railroads in the United States had actually been built on the East Coast before a steam engine was available to power them. Trains of cars pulled by horses looked a lot like stagecoaches on rails. But after Englishman George Stephenson’s locomotives began pulling passengers and freight in northwestern England in the mid-1820s, Americans quickly switched to steam. The first locomotive used to pull cars in the United States was the Tom Thumb, built in 1830 for the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad. Although Tom Thumb lost its maiden race against a horse-drawn train, Baltimore and Ohio owners were convinced by the demonstration of steam technology and committed to developing steam locomotives. The B&O railroad, which had been established in 1827 to compete with the Erie Canal, already advertised itself as a faster way to move people and freight from the interior to the coast. Adding steam engines accelerated rail’s advantage over canal and river shipping.

Questions for Discussion

- Why were canals and steam power so transformative?

- What was the advantage of railroads over steamships?

Factories housed machinery that was too large or too expensive to be used in home production or that used power sources like steam or water power that weren’t available to small-scale producers. The machines themselves usually displaced workers, like when the water-powered looms of New Lanark destroyed the careers of hand-loom weavers by producing large quantities of cloth at a low cost that the weavers couldn’t match. However, the new industries also created new jobs. And often, although it took fewer people to weave a given amount of cloth using the new technology, the new industries were usually producing products for much larger (sometimes even global) markets. So much cloth was made in the new industrial textile centers like New Lanark in Scotland or Lowell in America that there were often a lot of new jobs—sometimes more than had previously been available in that region.

The new factory jobs required less skill than artisanal craftwork, especially when the worker was making a larger number of standardized products. Previously, a carpenter needed to be a skilled craftsman to design and assemble a custom-built chair, but with industrialization, a less-skilled lathe operator could turn large quantities of legs that could be assembled into any number of chairs of a standard pattern. Workers doing lower-skilled jobs became as standardized as the things they made and could be employed at a much lower cost. While more people might be working in a new factory compared to an old-fashioned craft workshop, each worker’s wages would almost always be lower.

And starting a factory was not the same as starting a craft workshop. It was no longer a slow, organic process where an apprentice became a master craftsman, developed a clientele, opened his own business, then hired a few workers or apprentices of his own. The people who started factories were often not even experts at the process they were going to do; they were capitalists and investors who had access to the large sums of money needed to erect a factory and fill it with technology and workers. A class of owners grew who had little or no connection to the workers they employed.

In places like Russia, manual labor was the predominant mode of production until almost the mid-eighteenth century. Members of the Russian Empire did not actively embrace industrialized factories until the 1840s. Russian entrepreneurs were not interested in investing in steam engine technologies, preferring to use the forced labor of serfdom (landless domestic workers contractually owned by the members of the noble class), causing Russia’s productivity to lag beyond Western European nations. Manual labor was employed for the production of leather, furniture, foods, and textiles.

By 1845, the importation of machinery and tools had doubled, leading to increased production of paper and glass. The system of serfdom was reformed, ultimately leading to abolition in 1861. While reform allowed serfs to work for wages, abolition did not necessarily improve the workers’ lives and contributed to exorbitant taxation and the creation of barshchina—obligatory work serfs were required to do for the landowners. An agrarian crisis followed by a recession during the 1880s were the catalysts prompting the Russian government to embrace technology. By the end of the century, Russia had increased its pig smelting from 4% to one-third of all that was produced in the world. By the beginning of the nineteenth century, Russia installed mechanization processes in its textile, sugar, metal, coal, and steel industries. Industrial output rose steadily, as did employment. Capitalist modes of production were critical to Russia’s modernization.

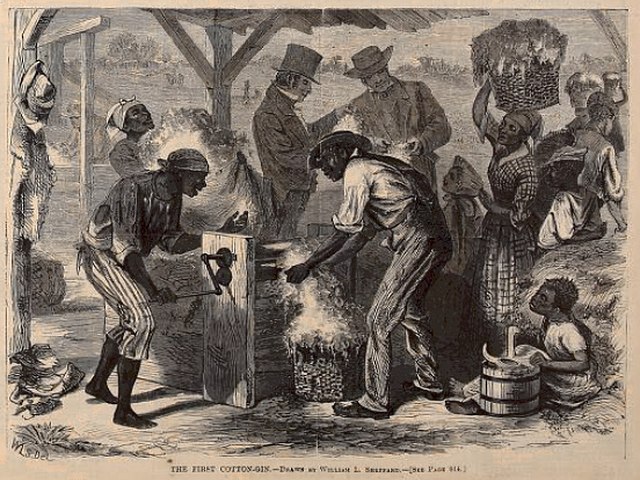

In the United States, industrialization revived a dying domestic slave trade. American inventor Eli Whitney (1765–1825) is remembered for the cotton gin, which removed the seeds from cotton fiber much more quickly than they could be picked out by hand. The cotton gin helped propel the American South into world leadership in raw cotton. By the 1850s, American plantations supplied 80% to 90% of the world cotton market. But Whitney’s most important contribution to industrialization was his technique for using machine tools to produce interchangeable parts for firearms. With Whitney’s standardized, machined parts, it no longer took a skilled gunsmith to build a weapon. Anybody with basic skills could assemble and also disassemble, repair, and maintain a rifle or handgun. Weapons became more reliable, and the technique was quickly applied to other industries. Of course, since most of the intelligence in the job had been moved into the machine, the machine gradually became more valuable and the machine operator less so. Whitney’s process made guns more reliable and less expensive, but he turned not only the gun parts into interchangeable parts but also the factory employees themselves. The process continues today: in the Tesla car factory, robots running sophisticated software do most of the skilled tasks like welding, while a smaller number of human workers spend most of their time moving assemblies from place to place and programming the robots.

Questions for Discussion

- How does technology affect workers and their jobs?

Socialism: Addressing the Negative Effects of Industrialization

Although it produced quality products at low prices for a growing consumer market, industrialization disrupted the lives of workers. Since jobs were in factory towns and cities, people moved from rural areas to growing metropolitan areas. The change was often very abrupt for those who migrated: they lost the slower rhythms of agricultural life to the time clock and subway schedules of the accelerated industrialized world.

Additionally, people were cut off from communities in which they had lived for generations and forced to find new social relations—or fall into lonely and desperate lives. Although jobs were the attraction for the new migrants, there was no guarantee of permanent positions in the new economy. Financial cycles of boom and bust affected urban workers the most. Families were disrupted by unemployment.

Men, women, and often children worked in factories to contribute to the family income. Only upper-class families could afford to educate their children. In urban settings, most boys typically began working around the age of 12. Women worked in textile factories and in mills as a way to be freed from parental oversight, as an alternative to domestic service, and as a way to supplement the family coffers. As the demand for mass goods increased, so did trade. The populations in, and near, industrial cities and towns doubled.

At the beginning of the nineteenth century, Europe controlled approximately one-third of the world’s industrialized and nonindustrialized nations. By the twentieth century, Europe claimed sovereign dominion of over 80%. Industrial output led to higher profits, whetting the appetites of European nations to continually seek raw materials, resources, and free labor.

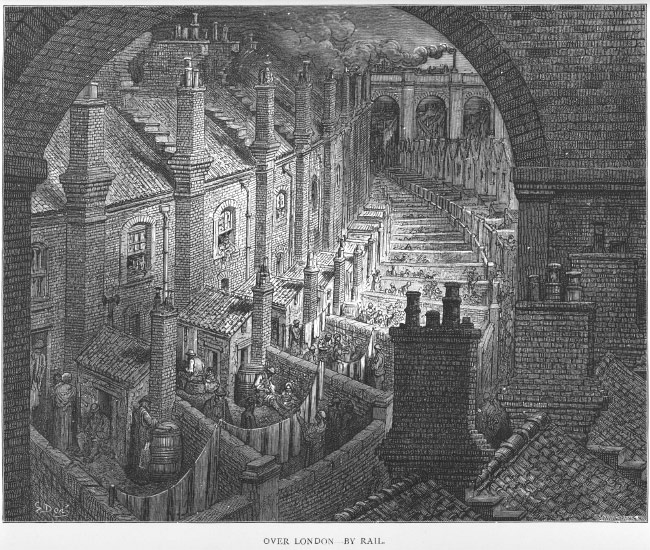

Cities were often unprepared to receive so many people so quickly. Inadequate housing, sanitation, and transportation contributed to environment degradation and psychological stress. In the following illustration of London in the 1840s, consider life for people who grew up on farms now living under these conditions, with no sign of plant life to be seen.

Many intellectuals took up the challenge of rethinking how to make society more just for industrial workers. While the U.S. War of Independence had inspired discussion of governments formed by “We the People,” and the French Revolution had spread the idea of legal equality of all citizens under law, a new understanding of capital and labor seemed to be needed. Workers in the new industries provided all of the labor at low wages and in dangerous conditions, while often absentee owners and investors reaped the profits. A number of industrialists such as Robert Owen tried to make their factories more humane, embracing the cooperative movement and even improving workers’ welfare with schools for their children and social gatherings. However, many business owners did not see their responsibility to workers extending beyond providing a wage for the work they performed.

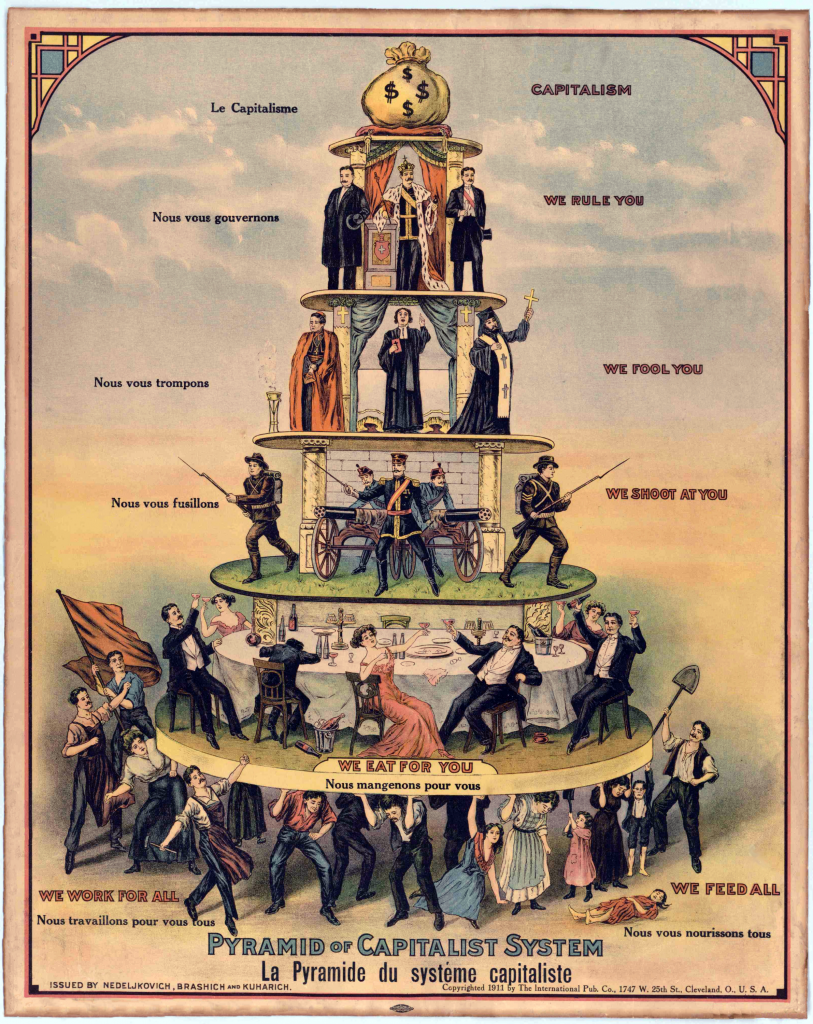

Karl Marx, a German philosopher, criticized the growth of capitalism and industrialization and brought a new analysis to economic thinking. Marx saw industrialization as the last stage of human development, a final struggle between two opposites that would create something new. According to Marx, this last struggle was between the more numerous workers, whom he called the proletariat, and the capitalists, the people with enormous financial resources who were also commonly called the “bourgeoisie” in French language at the time. Marx believed the proletariat would eventually inevitably defeat the bourgeoisie and seize the factories and other means of economic production, leading to the creation of a socialist state where the profit produced by labor was distributed evenly among workers. Over time, this socialist society would divide resources so that each individual would work “according to their ability” and each individual would receive resources “according to their needs,” resulting in the formulation of a communist utopia.

After the final battle, Marx predicted a world where the workers or their government controlled the “means of production,” the factories and farms. His views on religion are complex. Yes, he believed that religion was “the opiate of the people,” yet many have not examined the full quote. We need to remember that opium at this time was viewed as a reliable medical treatment for pain. In that context, “Religion is the sigh of the oppressed creature, the heart of a heartless world, and the soul of soulless conditions. It is the opium of the people” has a different meaning than it has been often ascribed. In essence, Marx distinguished between religion for individuals and the religious institutions of empires and nations. In his view, after the development of class consciousness and a worldwide series of proletarian revolutions, the workers would remain religious (or “spiritual,” to use contemporary terms), but the repressive institutions of the past would become inherently irrelevant. Marx imagined an unexploited and united global working class.

Karl Marx and his associate Friedrich Engels published their ideas in the Communist Manifesto in February 1848, just as Europe entered a year of numerous revolutions that were brutally suppressed. The work would go on to become the second most cited work in the social sciences. Since these upheavals did not bring the predicted dictatorship of the proletariat as expected, Marx and other revolutionary socialists continued to publish and organize the first Marxist socialist parties. He died in 1883, by which time various socialist and social democratic parties had participated in elections, but he did not live to see an actual “socialist” revolution, which would finally occur in Russia in 1917. Even so, by the time of Marx’s death, his ideas and other forms of socialism were motivating labor organizers to form unions in which workers could negotiate for better wages and working conditions with owners under threat of striking—stopping work at a factory and preventing others from replacing them at the machines. Socialism and communism, and their influence in governments and labor relations, will be examined more fully in later chapters.

Questions for Discussion

- Why did many workers find industrial cities challenging to live in?

- Consider socialism’s criticism of capitalism. Is it justified? Are Marx’s expectations realistic?

Agriculture and Industrialization

As mentioned previously, industrialization depends on a stable foundation of agriculture to provide enough food for workers to increase the population and provide enough food for people to eat. As farming becomes more efficient, not everyone needs to focus on subsistence, and workers are available to move to cities and take jobs in factories. The remaining farms become bigger and take on the responsibility of feeding the growing urban populations.

Earlier agricultural societies in Europe had depended on crop rotation to rebuild soils after periods of intensive planting. But as farmers saw an opportunity to earn money in the market, feeding urban industrial workers, some were unwilling to accept the idea that a significant portion of their farms would be fallow each year. They preferred to amend their soils rather than waiting for fertility to regenerate naturally. But few farmers had access to enough manure to supplement all their soil. Luckily, there was an alternative.

The first commercial fertilizers were made from guano, the droppings of seabirds living on islands off the western shores of South America. Guano comes from the Quechua Indian word wanu, which means any excrement used as a soil additive. Guano was dry, light, and highly concentrated. Natives of the Andes have mined guano on the coast and islands for at least 1,500 years, and Spanish colonial records noted that Inca rulers had considered protecting the cormorants that were the main source of guano so important that disturbing the birds’ nesting areas was a capital offense. Guano was carried from the coast up into the Andes on the backs of llamas for use on the terraced farms surrounding highland cities like Machu Picchu.

Although surrounded by ocean, the islands off the western coast of South America are arid. Like the deserts they face on the mainland, some experience no annual rainfall at all. Seabirds such as cormorants and pelicans have lived on these islands in the millions for thousands of years. Over that time, they’ve left literal mountains of droppings, which, due to the lack of rain, have simply piled up. The guano contains the ideal percentages of nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium to make it an excellent fertilizer without any mixing. It simply needs to be chopped off the mountain, ground up, and spread on fields.

The Prussian explorer Alexander von Humboldt visited the islands around 1802 and publicized guano’s value as a fertilizer throughout Europe. Seeing a lucrative business opportunity, Europeans and Americans fell on the area in a guano rush, and by the middle of the century, several nations had enlisted the work of Chinese peasants in a Pacific labor system that has been compared with the slavery of the Atlantic world. Although the Chinese workers were technically free, many were debtors who had been tricked into labor contracts promising work in California. Once they reached the guano islands and realized they had been duped, there was no way off. Over a hundred thousand Chinese workers were imported to the islands in the second half of the nineteenth century.

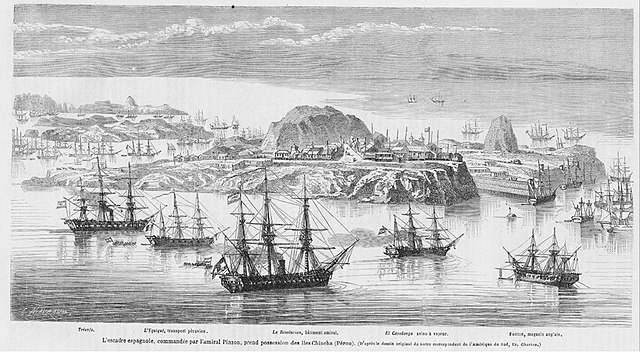

Guano was so profitable that the U.S. Congress passed a Guano Islands Act in 1856. The law provided an incentive for American sailors to find and claim undefended islands for America by giving the discoverer exclusive rights to the guano recovered. Islands claimed under the Guano Islands Act include parts of the Hawaiian chain, Midway Atoll, part of American Samoa, and several islands still disputed with Colombia. The guano islands off the western coast of South America were so valuable that two wars were fought over them. Chile and Peru fought Spain in the Chincha Islands War, 1864–66, and defeated the Spanish Empire. Then, once Spain’s claim had been successfully set aside, Chile took many of the guano islands from Peru, along with the nitrate fields of the Atacama Desert, in the War of the Pacific, 1879–83.

Defeating its northern neighbors in the War of the Pacific made Chile the undisputed power on the west coast of the Americas and generated an economic boom. The nitrate Chile monopolized was valuable both as a fertilizer and as a key ingredient in explosives and munitions. But mining and processing nitrate from Chile’s desert soil required much more capital than digging guano. Chile attracted British investors, and soon joint ventures began shipping a million tons of nitrate per year out of the South American desert. Production grew steadily until 1914, when World War I created new incentives for Britain’s enemies to find an alternative to Caliche nitrate. We will discuss this shift to an economic form of imperialism by European nations, Britain, and even the United States in the next chapter.

Industrialism and imperialism were often unpleasant bedfellows. Countries that were rich in resources but ungoverned by European monarchs were considered “fair game.” The largest unified attempt to control an entire continent is known as the Scramble for Africa. The Scramble for Africa (also known as the Partition of Africa or the Conquest of Africa) took place between 1881 and 1914, when European powers assigned territories to various European nations to colonize during the Berlin Conference. Germany, Italy, France, and Belgium were given permission to invade, annex, and colonize all but two countries, Liberia and Ethiopia. The small portion of Africa under European control prior to this meeting increased to almost 90 percent by 1914. Informal imperialism (imperialism masked as trade and treaty agreements) gave way to the outright militaristic ruling of African countries.

While Britain, France, and Spain were busy maintaining their established colonies all over the world, the king of Belgium was making a plan to stake his claim. Leopold II, née Léopold-Louis-Philippe-Marie-Victor, king of the Belgians (1865–1909), led the first European efforts to develop the Congo River basin. Leopold has been credited as being the sovereign founder and ruler of the Congo Free State. In colonizing the Kongo (now known as the Democratic Republic of Congo), Leopold is considered to have ordered the torture, sexual assault, and murder of millions of Congolese people while forcing them to plant, harvest, and process rubber trees, ivory, and minerals for exportation and sale to European and American corporations.

Leopold promised the other European heads of state that his establishment of the Congo Free State was a humanitarian mission that would bring infrastructure, access to education, and “civilization” to Central Africa. Instead, Leopold led a violent regime and employed the Belgian army to ensure the Congolese citizens were compliant. Those who did not produce their quotas were disciplined in the most inhumane ways—soldiers would cut off a hand or foot. Children were stolen from their families and transported to work in colonies processing the materials. Leopold’s reign was so violent that once American newspapers began publishing stories about the atrocities occurring, a great public outcry forced other European heads of state to condemn both Leopold and the Belgian government. The Belgian government ordered Leopold to step down but did not grant the Congolese their independence.

Questions for Discussion

- Why do you think Leopold II was able to get away with establishing a state on the continent of Africa?

19th-Century China and Japan

As described in Chapter 1, by 1500, under the Ming dynasty, the Chinese Empire was flourishing. There was rapid population growth, which in turn spurred on technological development, while a booming economy supported far-reaching international trade that in turn supported cultural development. Imperial officials were trained under a Confucian system that required them to pass difficult exams to achieve rank, meaning scholar-officials were adept and innovative. However, after tremendous successes, including the voyages of Zheng He, a degree of corruption and misrule crept into the Ming court by the next century, allowing the armies of the Manchu, from north of the Great Wall, to install the Qing dynasty in 1648.

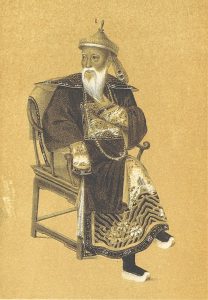

The new Qing emperors reinvigorated the Confucian ruling class, and China once again enjoyed a high degree of social stability, economic prosperity, and international trade. However, Qing society rested on the laurels of previous accomplishments, regarded foreigners as ignorant barbarians, and was not receptive to expanding European influence in the region, led by the British.

By the mid-1700s, the British East India Company was one of the most dominant organizations controlling the overseas trade of South Asia. British ships carried Indian cloth and other products to the rest of the world; the tea dumped in Boston Harbor in 1773 came from India. The East India Company was very interested in opening up Chinese markets to trade, but China was self-sufficient and uninterested in anything the British had to offer, especially since Spanish silver was already traveling from Bolivia and Mexico, through Manila—in the Spanish colony of the Philippines—to China. Chinese teas, jade, silks, and porcelain were in high demand in Europe, the eastern Americas, major cities in Central and South America, and throughout Southeast Asia. Trade tribute to various Chinese dynasties from Southeast Asia came in the form of luxury items, such as ivory and tortoise shells. Yet the only currency payment the Qing would accept from Europeans was silver, and the British East India Company’s supply of silver was limited.

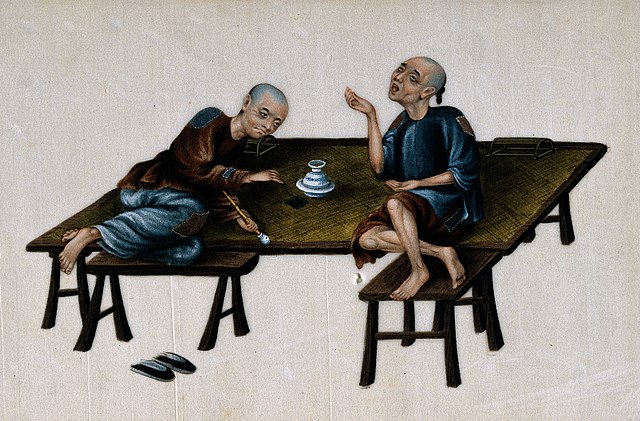

South Asia, especially Northern India, Bangladesh, and even Myanmar (then the Third Burmese Empire in Southeast Asia) provided the company with an alternative: opium harvested from poppies. Opium smoking had dramatically increased in the Qing Empire in the early 18th century, and the Yongzheng Emperor (r. 1722–35) had banned both the smoking and the sale of the drug. However, bans of a similar severity had not been enacted in the Burmese Empire and various South Asian states. The British East India Company learned the lesson of basic economic principles that moonshine bootleggers and international cartels would learn in later centuries: strict bans and criminalization only increase demand, and those who supply that demand can become wealthy beyond imagine. The company focused on importing opium into China, where users were willing to pay in silver. At the beginning of the 19th century, an annual average of 4,500 trunks of opium were reaching smugglers on the South China coast. By 1839, over 40,000 133-pound chests of opium were bought by Chinese drug dealers. More than 1% of China’s 400 million people became regular opium smokers, many of them rich bureaucrats. Qing China shifted from being a magnet for silver with a huge trade surplus to a net importer whose treasuries were rapidly dwindling.

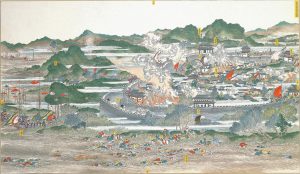

Some Qing officials wanted to legalize opium so the empire could tax it, but Confucian moralists won the policy debate. In 1839, the emperor sent one of China’s most distinguished officials, Lin Zexu, to the trading settlement of Canton to stamp out the opium trade. Lin blockaded the European trading district, raided and searched the foreigners’ warehouses, confiscated 20,000 chests containing 1,200 tons of opium, and dumped it all into the ocean. The East India Company complained about its losses in London, and Queen Victoria sent a fleet including four battleships. Lightly armored Chinese war junks, designed to fight river and bay pirates, were severely outgunned. The limited range of Qing cannons compared to British artillery allowed the invaders to pummel Chinese defenses from a safe distance.

The Treaty of Nanking (often called the “Unequal Treaty” in the Chinese language) opened five Chinese ports to European traders, gave the British the island of Hong Kong, and required the Qing Empire to establish diplomatic relations with Great Britain as an equal power rather than continuing to treat all foreigners as barbarians unworthy of official notice. The Qing were also compelled to pay Britain for the opium Lin had destroyed. Qing China’s embarrassing defeat by the British was followed by another defeat in the Second Opium War (1856–60) that resulted in another unequal treaty, giving access to French and Russian merchants. By the 1890s, 90 ports of call were available to more than 300,000 European and American traders, diplomats, and missionaries.

The weakness of the Qing Empire against foreign aggression was exacerbated by the ongoing opium crisis and by crumbling infrastructure and famine in the countryside. Magistrates and officials addicted to opium were ineffective and often diverted money that should have been spent maintaining dams and irrigation canals to their own uses. A series of peasant revolts swept through South China in the 1850s and 1860s, most notably the Taiping Rebellion, which killed 30 million people over a fifteen-year period. The leader of the rebellion was Hong Xiuquan, a young man who had become unhinged after failing the grueling civil service exam four times. Hong had a vision and declared he was the little brother of Christ who had been sent to China to rid the land of the Manchu foreigners and their Confucianist culture. When Hong captured Nanjing and in 1853 made it the capital of the Taiping, he first killed all the Manchu men and then marched the women outside the city and burned them to death.

Hong’s brutality and his strange interpretation of Christianity may have alienated some Europeans, but his ban on opium use antagonized more. Europe and Britain threw their support behind the Qing dynasty they had just defeated in the Opium Wars. Hong and his allies were unable to avoid the temptation to quarrel and plot against each other, which weakened their leadership. Two Taiping attempts to take Shanghai in 1860 and 1862 were repelled with British and French assistance. In 1864, the Qing and their European allies retook Nanjing and ended the regime, but the resistance continued until 1871, when the last Taiping army was completely wiped out by government forces.

The Taiping Rebellion was not the first rebellion Qing imperial officials had faced, nor was it the last. The previous White Lotus Rebellion (1796–1804) was a millenarian Buddhist rebellion in northern China that predicted the coming of the Buddha of the future: Maitreya. They also advocated for the restoration of the Ming dynasty. Even after they were brutally repressed, a subgroup of the White Lotus school of Buddhism supported another rebellion in provinces in the central-northeast of China in 1813, called the “Eight Trigrams” rebellion. After the Taiping Rebellion emerged out of the south, a virtually simultaneous anti-Qing rebellion broke out in northern China called the Nian Rebellion (1851–1868). Then Hui Muslim separatists revolted in Yunnan province in southern China under the leadership of Sulayman ibn ‘Abd ar-Rahman, known as Du Wenxiu in Chinese, from 1856 to 1872, in an uprising frequently called the “Pathan Rebellion” in British sources from the time. The suppression of the Chinese Hui Muslims led to their migration to what is now Laos, Thailand, and Myanmar (Burma), where there are still significant populations of Hui Muslims today. Hui Muslims also revolted in northern China from 1862 to 1877. Although this was separate from the revolt of Hui Muslims in the south, it is notable that one of the Qing commanders, Zuo Zongtang, was involved with suppressing the Taiping, Nian, and the so-called First Dungan Revolt of northern Hui Muslims. However, Hui Muslims were not always antagonistic to the Qing dynasty. Indeed, during the 18th-century Jahriyya revolt, the Qing dynasty employed Khafiyya Sufi Muslims to put down the revolting Jahriyya Sufi school. Furthermore, during the Second Dungan Revolt (1895–1896) Hui Muslims ended up on both sides of the fighting. Finally, a revolt against European and Japanese influence would round off the troubled 19th century in Qing China.

In the mid-1880s, a group called the Yihetuan (League for Harmony and Justice) was formed in the northern provinces of Shandong and Zhili. Sometime around 1898–1899, they changed their name to the “Plum Blossom Fists” (Meihuaquan), or alternatively, the “Fists of Harmony and Justice” (Yihequan). They were clearly influenced by previous rebellious secret societies, like the White Lotus school, although Yi-he martial arts—often misnamed “Chinese boxing” in English—came to be popular sometime in the late 18th century. An initial Qing investigation in 1898 found some 10,000 trained soldiers in the north, composed mostly of people who were peasants and not literate in Mandarin Chinese. Initially, they did not appear to be a treat, but in March 1898, they took to the streets with the slogan “Uphold the Qing, destroy the foreigners!”

The “Fists of Harmony and Justice” first battled with Qing troops in 1899 and began to attack Christian missionaries who they considered to be “polluting” Chinese culture. Hardliners in the court, such as Prince Duan, joined their cause, and Prince Duan arranged for a meeting between the so-called Boxer leadership and the Empress Dowager Ci Xi. They would thus amass a force of nearly 300,000 “Boxers” and some 100,000 Qing troops. However, the intervention of foreign armies of the Eight Nation Alliance worked with a significant force of the Mutual Protection of Southeast Asia, who were mostly composed of Han (ethnic Chinese and anti-Qing) provincial leaders, to put down the so-called rebellion in 1901. Although the Eight Nation Alliance was mostly made up of a force of some 2,000 British marines, with smaller numbers from France, the United States, the German Empire, the Kingdom of Italy, and Austria-Hungary, the most significant contributions to the Eight Nation Alliance came from the Russian Empire and Japan. While the Russian Empire added a standing army of 12,400 (some 2,000 more infantrymen than the British), 750 marines, and 10 warships, the Empire of Japan provided almost half of the infantry and almost a third of the warships to the alliance, adding 20,300 men to the fighting forces and 18 warships to the allies.

By comparison to the Japanese forces, the “contributions” of France, the United States, the German Empire, the Kingdom of Italy, and Austria-Hungary were symbolic, amounting to between 10% and 25% of those of the Japanese Empire. However, at the signing of the Boxer Protocol, war reparations as indemnity were mostly paid from the Qing Empire to Russia (29%), Germany (20%), France (15%), and Britain (11%). Japan only received 7% under the indemnity clause, virtually the same as the United States and Italy. Relations in the Pacific region thus remained troubled and unequal into the 20th century, as the Qing Empire struggled to retain control over increasingly dissatisfied ethnic Han (ethnic Chinese) and peasants.

Elsewhere in Asia, Japan’s insular self-confidence was also challenged in the 19th century. The Japanese home islands have been united under the same imperial dynasty since the 5th century CE; the current emperor comes from the longest line of any monarch in the world. As an independent island nation, the Japanese were able to selectively accept or reject ideas and innovations from China, the powerful empire to the west. Often they would modify and incorporate aspects of Chinese culture, like writing and Buddhism, to their own circumstances; indigenous Japanese Shinto religion, for instance, embraces the teachings of Buddha.

Beginning in the late 1100s, the emperor ruled indirectly, ceding power to Shoguns, who commanded an army of lesser nobles known as samurai. The Shoguns held back invasions by Mongol armies in the 1200s and maintained a large degree of separation for the empire from outside religions and cultures, although they maintained connections through the independent Ryukyu Kingdom (Okinawa Islands, 1429–1879), and by the 17th century, significant Japanese overseas communities called “Nihonmanchi” became prominent in Southeast Asia. These Nihonmanchi established trading connections across Southeast Asia, as sugar, spices, precious woods, and silk were sent to Japan. However, during the Tokugawa period, new trade restrictions were put in place, and trade became more mediated, with the aforementioned Ryukyu Kingdom becoming an important intermediary. Additionally, the Japanese Empire was wary of European influence and kept most European nations, along with the United States, at an arms’ distance. However, refusing to accept the empire’s right to self-determine its own trade policies, the United States—which had also been virtually shut out of the profitable ports of Qing China—began to look toward the Japanese Empire for opportunities for expansion.

American Commodore Matthew Perry sailed into Tokyo Bay in July 1853 with a squadron of four warships and threatened to open fire on the capital if the Japanese imperial officials refused to negotiate. To demonstrate the capability of the squadron, Perry destroyed several buildings around the harbor without provocation. The American fleet withdrew to allow the Japanese officials time to consider their options, and when they returned a year later, the Japanese agreed to a “Treaty of Peace and Amity.” Three years later, a “Treaty of Amity and Commerce” was signed, offered to the Japanese by American diplomats as a less-invasive alternative to the aggressive colonialism of Britain and France in Qing China following the Opium War.

The words of Shimazu Nariakira are often cited as evidence of the Japanese position: “If we take the initiative, we can dominate; if we do not, we will be dominated.” But Shimazu Nariakira was actually a feudal lord (daimyo) who had died in 1858. Nonetheless, he is often viewed in retrospect as a quintessential “modernist,” as he held the position that the Japanese Empire to adopt new ways of learning and technology, whether they were from Asia, the Americas, or Europe. Modernization and the embrace of new technology went hand in hand with reorganization of the national government in what became known as the Meiji Restoration. The 15th Tokugawa shogun resigned in November 1867, and direct control of government was restored to the Emperor Meiji. The samurai class (which numbered nearly 2 million) was slowly disbanded, and a nationwide universal military draft was instituted in 1873. Disgruntled samurai rebelled in 1876; the Satsuma Rebellion grew into a short civil war in which the newly formed Imperial Japanese Army won a decisive victory. The industrialization of Japan accelerated, building the strong nation we will see taking its place on the world stage in the next chapter.

Furthermore, in 1895, China lost its control of its tribute state Korea to Japan in the First Sino-Japanese War (1894 to 1895). As part of the treaty negotiations, the Qing Empire ceded Taiwan and Penghu—an archipelago of 90 islands and islets in the Taiwan Strait—to the Empire of Japan. Taiwan would thus become a staging ground for the expansion of Japanese influence in Southeast Asia over the coming decades. The humiliating defeat of the Qing Empire showed that their efforts to modernize China’s military had failed and was a catalyst for a series of political actions led by revolutionaries, including the nationalist Sun Yat-sen.

Questions for Discussion

- Compare the Taiping Rebellion to the U.S. Civil War, which happened about the same time. How were the two conflicts similar and different?

- Why do you think Japan was more able to rapidly respond to the challenge of Western culture?

Primary Sources

LIN ZEXU, LETTER TO QUEEN VICTORIA (1839)

Looking over the public documents accompanying the tribute sent (by your predecessors) on various occasions, we find the following: “All the people of my country, arriving at the Central Land for purposes of trade, have to feel grateful to the great emperor for the most perfect justice, for the kindest treatment,” and other words to that effect. Delighted did we feel that the kings of your honorable nation so clearly understood the great principles of propriety, and were so deeply grateful for the heavenly goodness (of our emperor):—therefore, it was that we of the heavenly dynasty nourished and cherished your people from afar, and bestowed upon them redoubled proofs of our urbanity and kindness. It is merely from these circumstances, that your country—deriving immense advantage from its commercial intercourse with us, which has endured now two hundred years—has become the rich and flourishing kingdom that it is said to be!

But, during the commercial intercourse which has existed so long, among the numerous foreign merchants resorting hither, are wheat and tares, good and bad; and of these latter are some, who, by means of introducing opium by stealth, have seduced our Chinese people, and caused every province of the land to overflow with that poison. These then know merely to advantage themselves, they care not about injuring others! This is a principle which heaven’s Providence repugnates; and which mankind conjointly look upon with abhorrence! Moreover, the great emperor hearing of it, actually quivered with indignation, and especially dispatched me, the commissioner, to Canton, that in conjunction with the viceroy and lieut.-governor of the province, means might be taken for its suppression!

Every native of the Inner Land who sells opium, as also all who smoke it, are alike adjudged to death. Were we then to go back and take up the crimes of the foreigners, who, by selling it for many years have induced dreadful calamity and robbed us of enormous wealth, and punish them with equal severity, our laws could not but award to them absolute annihilation! But, considering that these said foreigners did yet repent of their crime, and with a sincere heart beg for mercy; that they took 20,283 chests of opium piled up in their store-ships, and through Elliot, the superintendent of the trade of your said country, petitioned that they might be delivered up to us, when the same were all utterly destroyed, of which we, the imperial commissioner and colleagues, made a duly prepared memorial to his majesty;—considering these circumstances, we have happily received a fresh proof of the extraordinary goodness of the great emperor, inasmuch as he who voluntarily comes forward, may yet be deemed a fit subject for mercy, and his crimes be graciously remitted him. But as for him who again knowingly violates the laws, difficult indeed will it be thus to go on repeatedly pardoning! He or they shall alike be doomed to the penalties of the new statute. We presume that you, the sovereign of your honorable nation, on pouring out your heart before the altar of eternal justice, cannot but command all foreigners with the deepest respect to reverence our laws! If we only lay clearly before your eyes, what is profitable and what is destructive, you will then know that the statutes of the heavenly dynasty cannot but be obeyed with fear and trembling!

…

Your honorable nation takes away the products of our central land, and not only do you thereby obtain food and support for yourselves, but moreover, by re-selling these products to other countries you reap a threefold profit. Now if you would only not sell opium, this threefold profit would be secured to you: how can you possibly consent to forgo it for a drug that is hurtful to men, and an unbridled craving after gain that seems to know no bounds! Let us suppose that foreigners came from another country, and brought opium into England, and seduced the people of your country to smoke it, would not you, the sovereign of the said country, look upon such a procedure with anger, and in your just indignation endeavor to get rid of it? Now we have always heard that your highness possesses a most kind and benevolent heart, surely then you are incapable of doing or causing to be done unto another, that which you should not wish another to do unto you!

…

Our celestial empire rules over ten thousand kingdoms! Most surely do we possess a measure of godlike majesty which ye cannot fathom! Still we cannot bear to slay or exterminate without previous warning, and it is for this reason that we now clearly make known to you the fixed laws of our land. If the foreign merchants of your said honorable nation desire to continue their commercial intercourse, they then must tremblingly obey our recorded statutes, they must cut off for ever the source from which the opium flows, and on no account make an experiment of our laws in their own persons! Let then your highness punish those of your subjects who may be criminal, do not endeavor to screen or conceal them, and thus you will secure peace and quietness to your possessions, thus will you more than ever display a proper sense of respect and obedience, and thus may we unitedly enjoy the common blessings of peace and happiness. What greater joy! What more complete felicity than this!

Let your highness immediately, upon the receipt of this communication, inform us promptly of the state of matters, and of the measure you are pursuing utterly to put a stop to the opium evil. Please let your reply be speedy. Do not on any account make excuses or procrastinate. A most important communication.

QUOTES FROM ROBERT OWEN

“To preserve permanent good health, the state of mind must be taken into consideration.” (The Book of the New Moral World)

“Eight hours daily labour is enough for any human being, and under proper arrangements sufficient to afford an ample supply of food, raiment and shelter, or the necessaries and comforts of life, and for the remainder of his time, every person is entitled to education, recreation and sleep.” (“Foundation Axioms of Society for Promoting National Regeneration,” 1833)

“Is it not the interest of the human race, that everyone should be so taught and placed, that he would find his highest enjoyment to arise from the continued practice of doing all in his power to promote the well-being, and happiness, of every man, woman, and child, without regard to their class, sect, party, country or color?” (17th of “20 Questions to the Human Race,” 1841)

“As there are a very great variety of religious sects in the world (and which are probably adapted to different constitutions under different circumstances, seeing there are many good and conscientious characters in each), it is particularly recommended, as a means of uniting the inhabitants of the village into one family, that while each faithfully adheres to the principles which he most approves, at the same time all shall think charitably of their neighbors respecting their religious opinions, and not presumptuously suppose that theirs alone are right.” (Rules and Regulations for the Inhabitants of New Lanark)

“The working classes may be injuriously degraded and oppressed in three ways:

1st—When they are neglected in infancy

2nd—When they are overworked by their employer, and are thus rendered incompetent from ignorance to make a good use of high wages when they can procure them.

3rd—When they are paid low wages for their labour (Two Memorials on Behalf of the Working Classes)

“To train and educate the rising generation will at all times be the first object of society, to which every other will be subordinate.” (The Social System)

“To preserve permanent good health, the state of mind must be taken into consideration.” (The Book of the New Moral World)

MANIFESTO OF THE COMMUNIST PARTY, MARX & ENGELS, 1848

In proportion as the bourgeoisie, i.e., capital, is developed, in the same proportion is the proletariat, the modern working class, developed—a class of laborers, who live only so long as they find work, and who find work only so long as their labour increases capital. These laborers, who must sell themselves piecemeal, are a commodity, like every other article of commerce, and are consequently exposed to all the vicissitudes of competition, to all the fluctuations of the market.