10 Decolonization

Steps toward Decolonization, 1945–1960

Decolonization began at a unique time in history, just when the U.S.-Soviet Cold War was heating up. The superpowers sought allies among the newly independent states, and this at times greatly impacted the process of self-determination, as the cases of India, Algeria, and Vietnam highlight. Still, the needs of the newly independent states will continue to exert themselves, as the Green Revolution, beginning in the 1960s, will show.

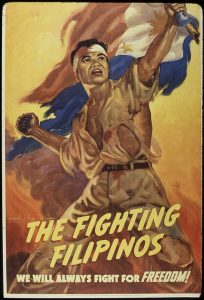

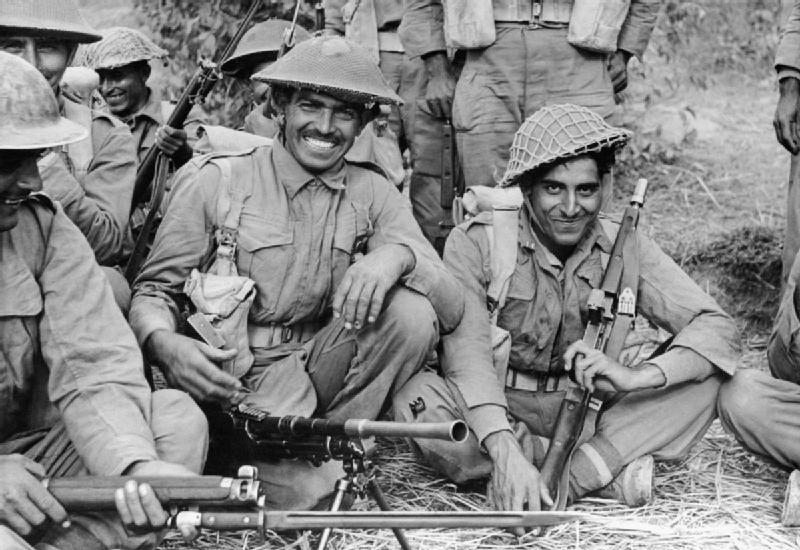

In many regions under imperial control, the struggle for independence had begun long before World War II. As you’ll recall from previous chapters, European and American justifications for empire included the claim that people such as Britain’s subjects in India and the America’s in the Philippines were unprepared to stand on their own as independent nations. This claim was undermined by the effectiveness of the Indians and Filipinos in World War II. Filipinos had proven their value as guerrilla fighters, while the British Indian Army fought valiantly in all theaters of the war. The defeat of Nazi Germany and the Japanese Empire freed the people of the nations these two would-be empires had conquered, but many people dominated by older empires had already questioned the legitimacy of imperialism for decades and were ready to seize the moment.

At the close of World War II, European imperialist powers like Britain, France, and the Netherlands assumed colonial populations would not object to their return. British imperialists like Winston Churchill hoped and expected to expand their empire, which they had renamed a commonwealth in 1931. But both the British and the French governments had made important promises of greater freedoms and self-determination during the war in return for help defeating the Nazis. In many cases, these promises inspired existing nationalist movements—such as those in Ghana, Algeria, and elsewhere—to grow, strengthening their cohesion, organization, and militancy. Many, if not most, British and French officials retained their sense of cultural superiority and convinced themselves that their help was still needed to “assist primitive peoples in their march to modernity.” Even among the political left in those countries, most remained committed to elements of imperial as a means to strengthen the labor movement in their countries.

The timing of national liberation was complicated by the growing conflict between the United States and the Soviet Union known as the “Cold War,” covered in the following chapter of this book.

Between 1945 and 1960, there were over three dozen colonies that won or regained their independence, primarily from Asia and Africa, establishing almost as many new nations. The United Nations offered the new countries a place to find friends and voice their interests. The United Nations established “trusts” over 11 former German and Italian colonies (including Tanganyika, Italian Somaliland, Cameroons, and Togoland) with the goal of bringing these colonies to independence. In all cases, the colonies’ economies remained tied to that of their colonizer, and it would be a gradual process to find ways to better diversify and spread out economic activity. Finally, in 1960, as a testament to the times, the United Nations adopted the Declaration on Granting Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples, although the organization would not admit the former Portuguese colonies of Angola and Mozambique until the middle of the 1970s, while the former Portuguese colony of East Timor only proclaimed independence in 1975, and Macau remained a Portuguese colony until 1999.

As so many countries across Asia and Africa were becoming independent, both the United States and the Soviet Union competed to expand their spheres of influence by claiming allies. The United States frequently nudged their European allies to grant it concessions to their colonies to ensure the colonies would continue to support Western Cold War goals and economic objectives. For its part, the Soviet Union offered attractive-sounding alternatives that referenced industrialization without exploitation and a better future for all people, not just for the few capitalists poised to profit. The communist victory establishing the People’s Republic of China in 1949 and advances in places like Egypt, Ghana, and Vietnam, where prominent nationalists were not afraid to reference socialism or communism, brought a growing fear in the United States that decolonizing states would become more closely aligned with the Soviet Union, threatening the potential of American economic power.

Despite the Cold War, at times the process of independence was occasionally achieved through mutual agreement. However, these mutual agreements did not represent independence granted for benevolent means. In the Philippines, for example, the U.S. government handed over power to a local Filipino government within a year of ending the war with Japan. In exchange, the American government gained political allies to help brutally repress one of the most successful anti-Japanese militia groups: the Hukbalahap. While many Americans appreciated the sacrifices made by the Filipinos under Japanese occupation, anti-Asian sentiment in the United States was still widespread, and transforming the Philippines from a territory into a commonwealth to be later granted independence had pandered to domestic anti-Asian sentiment in the 1930s. While some Americans questioned direct colonial acquisitions, most took it for granted that this was an American possession, if they had heard about it at all, and were ready to support a formal independence and revert to a more informal form of influence. President Truman recognized the independence of the Philippines on July 4, 1946. In the days leading up to the announcement, the American and Filipino governments worked out arrangements allowing the U.S. to retain dozens of military bases and for American businesses to have preferential access to the raw materials and markets of the newly independent nation.

The imbalance of power that these agreements set in place increased the popularity of the left-wing Hukbalahap rebels, who, backed by widespread support among the majority of tenant farmers in the largely agrarian society, frequently protested economic conditions. In response, American allies such as Manuel Roxas, Elpidio Quirino, and Ramon Magsaysay attempted to portray themselves as democratic reformers. However, each took an authoritarian approach to the Hukbalahap movement. Roxas expelled them from political participation. Quirono offered Hukbalahap leaders an amnesty agreement, but then stepped up persecution of political dissidents, using their supposed violation of the very same agreement as justification. Finally, after he won a landslide election in 1953—with the partial help of American and especially CIA backing—Magsaysay continued a brutal all-out military campaign against any form of dissent. While they had numbered 50,000 in 1950, there were just an estimated 2,000 remaining Hukbalahap forces by 1954. As a populist right-wing nationalist, Magsayay retained the support of the United States, and after he died in a plane crash in 1957, the state held a massive funeral with two million onlookers in an effort to emphasize his popularity among “the people.” This brand of right-wing nationalist populism paved the way for Ferdinand Marcos to rise to power by 1965, as the previously common practices of abuse of power became more prominent. Marcos’s authoritarianism would rule the Philippines for two decades, backed by American support in the name of anti-communism for the duration of that regime.

For another case where the liberation of a country has been often considered “peaceful” but the reality was more complex, we turn from Southeast Asia to South Asia: specifically India. Many academics and political leaders have hailed the story of Indian independence as the prime example of how non-violent protest, boycotts, and moral suasion could result in freedom. However, there are also many more cases in which independence was only achieved through a more violent guerrilla struggle, as European imperialists were unwilling to let go of their colonies despite the desires of the colonized. Furthermore, in the case of India, to say that the decolonization process itself was without violence would simply be inaccurate. Indeed, the process of decolonization in the subcontinent is a long history, beginning with the founding of the nascent nationalist India National Congress (INC) in 1885. INC members were frequently violently repressed throughout their struggles. Nonetheless, there were many violent rebellions in a wide variety of Indian states in the early 20th century. The linkages between these violent rebellions and the later success of the INC’s non-violent movement is still a matter of debate among historians.

Questions for Discussion

- Why did leaders like Churchill believe they would be able to return to controlling their empires?

- Why did colonized people disagree?

Independence and Partition in British India

One of the earliest examples of decolonization in the post-war era and one that affected an extremely large portion of the world’s population was the British withdrawal from India. India’s long struggle for independence had been led by the aforementioned India National Congress party.

After 700,000 Indians fought for Britain in the Great War, over 2.5 million soldiers from India fought alongside the British in World War II. More than 87,000 of them were killed in action. The British field marshal in charge of the Indian Army from 1942 onward said Britain “couldn’t have come through both wars [World War I and World War II] if they hadn’t had the Indian Army.” When Britain called Indians to arms a second time, the Muslim League supported the British recruitment. However, the Indian National Congress demanded independence before it would agree to help Britain again. When the congress began a “Quit India” campaign in August 1942, the British imprisoned tens of thousands of leaders for the war’s duration until June 1945. Mohandas Gandhi was among those jailed; he was released in May 1944 due to health concerns.

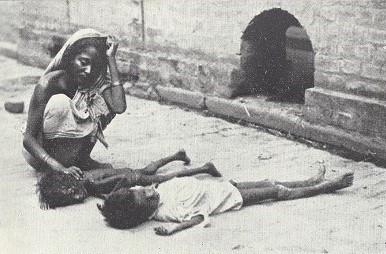

British war strategy led to a major famine in Bengal in 1943 (modern-day Bangladesh, at the mouth of the Ganges River), and about 3 million people died of starvation. The Japanese invasion of Burma (now Myanmar, then part of British India) caused about a half million Indian Hindu refugees to flee to neighboring Bengal. At the same time, the British decided to adopt a “scorched-earth” policy in southern Bengal, burning thousands of boats and destroying rice crops so they would not fall into the hands of the Japanese, who they assumed would soon extend their invasion. Poor harvests and wartime inflation in late 1942–early 1943 sent internal rural refugees into Calcutta, the Bengali capital, exacerbating the crisis. The British War Cabinet stalled in sending needed grain to the starving Bengalis. In effect, the British policies had decided that Bengali lives were not worth the potential strain on wartime shipping. When presented with evidence of the massive famine, Prime Minister Winston Churchill was incredulous, asking, “Why hasn’t Gandhi died yet?” His denial that there was even a problem was a response strikingly similar to Stalin’s treatment of the famine in Ukraine, Georgia, and southern Russia during the previous decade. However, Churchill’s record on Indian independence remains mixed.

Churchill was not only aware of Gandhi; he was aware of the importance of India to the British war effort. In addition to 2.5 million soldiers, the British government borrowed billions of pounds from India to finance the war. And India was no longer merely a site of famines; it was becoming a source of essential supplies. By the end of the war, India had become the world’s fourth-largest industrial power, and its increased economic and military influence paved the way for independence from the British Empire in 1947.

However, Indian independence was complicated by internal divisions—which eventually led to the partition of India and Pakistan—especially as religious and ethnic factionalism was exacerbated by the British themselves during many decades of imperial rule. In particular, the British had encouraged division between the majority Hindu and minority Muslim populations, sending Hindu troops to police the Muslims and vice versa. Gandhi sought to eliminate the Hindu caste (jati) system, which deprived the poorest Indians of hope, although he maintained that the ideas of a class (varna) system were a valuable part of the stability of Indian society. Caste was an integral part of Hinduism historically, but under British rule, the system had been expanded and the number of divisions had been increased because the foreign rulers found it useful in their divide-and-conquer strategy. In particular, in regions where ethnic or religious divisions were prominent, British law divided Muslims into castes as well, even though Muslims often rejected such class- and birth group–oriented distinctions, except by which means they might designate distinction from surrounding Hindu communities.

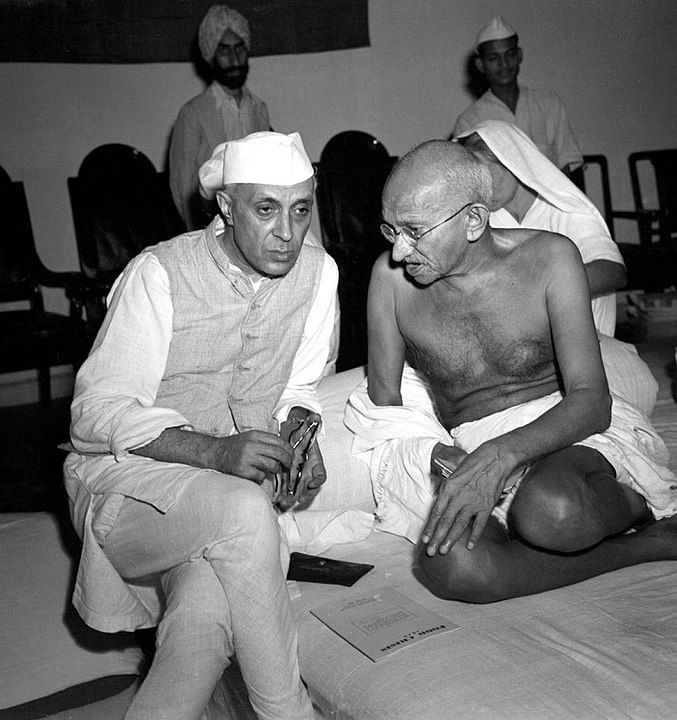

Religious divisions seeped into the independence movement as well. While Gandhi simply wished for an independent, united India after the end of British rule, Muhammad Ali Jinnah and the Muslim League lobbied for the establishment of two states in the territory. Earlier, far-right Hindu nationalists had proposed ridding India of the Muslim-minority population. Seeing no way to fight this idea, Mohammed Jinnah, a Muslim nationalist leader, leaned in and supported the creation of an Islamic state, to be called “Pakistan.” As independence was being negotiated after the war, escalating religious violence suggested that British withdrawal might result in an all-out bloody civil war, potentially costing tens of millions of lives. Hundreds upon hundreds of people had already died as Muslim and Hindu mobs attacked each other in different towns and cities. Congress Party leader Jawaharlal Nehru (who would become the first prime minister of India) met frequently with Mohammed Jinnah, and the two negotiated the partition of India from Pakistan. The new Muslim nation at the time included both the present territory of Pakistan in the west and the eastern region now called Bangladesh, over 2,000 kilometers away.

After independence in August 1947, the partition created a central Hindu nation with two borders into Muslim Pakistan to the east and west. These new, arbitrarily drawn borders resulted in the displacement of 10 to 20 million people, as the former British subjects fled their homes to join the new nations that matched their religions. Millions died during the chaos of the migration and the refugee crises that followed. But even partition was not enough for some Hindu nationalists. Gandhi himself was assassinated by one such extremist from the far-right Hindutva extremist organization, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, shortly after he achieved his dream of independence in January 1948.

Not only was partition an imperfect solution to religious differences the British Empire had exacerbated, but the arbitrary borders were drawn hastily by a British official with little to no prior knowledge of the region. As a result, the states of Jammu and Kashmir in Northern India and Pakistan are still disputed territory. In 1947, a local Hindu prince convinced the British that the majority-Muslim region should stay with India. The government of Pakistan and many local Kashmiris continue to protest this, causing internal and external conflicts. Since both India and Pakistan are now nuclear nations, the ongoing Kashmir dispute is a legacy of imperialism that may still endanger regional or even global peace.

Questions for Discussion

- In what ways were the British responsible for the antagonism between India and Pakistan since independence?

Israel and Palestine

India was not the only region of the world from which Britain walked away soon after World War Two. Another was Palestine. After World War I, Britain had been given a “mandate” by the League of Nations to administer Palestine along with the oil-rich regions of Arabia and Iraq. Between the wars, the British continued to allow Jewish Zionists—who advocated the reestablishment of a Jewish homeland in Palestine to provide their people with a haven, protected from the anti-Semitism of Europe—to purchase land and move into the region. Migration of Zionists to the region had begun in the late nineteenth century. This “second wave” of Zionist settlers included numerous dedicated socialists, who created cooperative farms called kibbutzim, and urban Europeans, who built cities like Tel Aviv—one of the prime examples of the Bauhaus architectural style popular in Germany in the 1920s. However, accelerating Zionist immigration increased tensions with the Palestinians, who had lived in the region for millennia. Competition for land and water, as well as for political dominance, resulted in violent riots between Arabs and Zionists in 1921 and a longer Arab nationalist revolt in Palestine from 1936 to 1939.

As mentioned previously, the Nazi Holocaust, coupled with lingering anti-Semitism in Britain, France, and Spain, was evidence of the Zionist nationalist thesis: Jews would never be safe in Europe and needed to establish their own independent state. In fact, in 1933, Zionists had signed the Hekem Havarah agreement, which would guarantee the safe passage of Jews to Palestine, specifically on the premise that it also coalesced to the Nazi goal of ridding Germany of the Jewish population there. While the British considered a petition to allow 100,000 refugee survivors of the Nazi camps to resettle in Palestine, political support for the movement was split between anti-Semites who did not want Jews in Britain and humanitarians who believed in the rights of Jewish people. Nonetheless, the British government hesitated due to opposition from Palestinian Arabs and the nearby Arab states. Zionist settlers had already formed a mutual defense force, the Haganah, in the 1920s. After the war, the Haganah turned to sabotage against the British occupation and organizing illicit arms shipments.

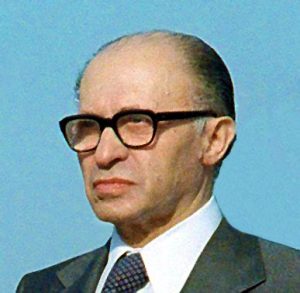

More radically militant organizations also formed, including the Irgun, which in 1946 bombed the British headquarters at the King David Hotel in Jerusalem, killing 91 people. The Irgun also led a terror attack on the Palestinian town of Deir Hassin in 1948, in which over a hundred perished, including women and children. Despite apologies from more mainstream Zionist groups (and later, an official apology from the government of Israel), the Deir Hassin massacre has served as a rallying cry for the Palestinian liberationist movement ever since.

In 1947, the British relinquished their “mandate” over Palestine to the new United Nations, which tried to develop a new map for a Jewish homeland—the new state of Israel—while taking into account the presence of the Arab Palestinians. Among Palestinians, the vast majority were Muslim, although a small minority were Christian. However, Jewish Zionists received more land than could be justified by their numbers at the time, as well as some of the more valuable agricultural and water resources, based on the argument of British officials that more Jews would assuredly arrive in Israel. As the British withdrew in May 1948, Israel declared its independence based on the U.N. borders, which both the local Palestinians and the neighboring Arab countries had rejected. Israel’s new neighbors immediately declared war, but the new nation had powerful allies, including the United States, and was willing to fight for its survival. Israel defended itself and actually extended its borders. Militant nationalists within the government of Israel claimed they needed to have a wider defensive perimeter and that the Arab Palestinians had abandoned many of their towns anyway, which many had because they thought the Arabs would win a decisive victory. Israel eventually destroyed over 500 Palestinian villages and cleared out Palestinian neighborhoods in major cities, causing the over 800,000 “temporary” Muslim and Christian war refugees to seek more permanent shelter in neighboring Arab nations. A series of wars in 1948, 1956, 1967, 1973, and 1982 continued the conflict.

With tenacity and insurmountable aid from the United States and Europe, the Israeli military held their own in these conflicts and embraced an ongoing expansion of the Israeli area of settlement in a policy of creating “facts on the ground.” Israel became the only nuclear armed power in the region. Many new states in the Muslim world, considering Israel an arbitrary creation of “Western powers”—by which they meant the members of the NATO block, especially France, and the United States—refused to recognize Israel as a legitimate state in their efforts to show solidarity with the repressed Palestinian population. Peace processes with individual Arab nations have brought agreements and diplomatic recognition from Egypt in 1979, to whom Israel returned the Sinai Peninsula, taken in the 1967 war, and Jordan in 1994, which relinquished its claim to the Palestinian West Bank of the Jordan River.

Weariness with war and a desire to qualify for U.S. military and economic aid led the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, and Sudan to recognize Israel in 2020. Indeed, 165 countries recognize the state of Israel today, including most countries with significant Muslim populations. However, Cuba, North Korea, and Venezuela still do not. Furthermore, many of the same countries recognize Palestine. Indeed, the vast majority of the countries in the United Nations—a total of 138, almost all of Asia, Africa, and South America—recognize the State of Palestine today, although the United States, Canada, and much of Western Europe do not.

But it is one thing to have recognition from a government and another thing to be accepted as a nation by the “Arab Street.” During the course of the Arab Spring in the early 21st century, it became clear that Arab people were tired of authoritarian rule in their own countries, and there is much popular sentiment that is more supportive of the Palestinian cause than the governments ruling them.

Questions for Discussion

- Is it surprising that Palestinians resent Israel’s existence?

- Do you think the major issue is anti-Semitism, when both Muslim and Christian Arabs have fought Israel?

- How might the extremely high level of financial and military aid Israel receives from the U.S. complicate Middle Eastern diplomacy for both the Israelis and the Americans?

“British” Kenya

Although Great Britain had retreated relatively peacefully from India and had given up its control over Palestine voluntarily, this was not the universal pattern. Reluctance to abandon colonies was especially a problem in Africa, where there were British settlers rather than administrators. By the early twentieth century, 30,000 British settlers occupied all the best farmland in Kenya, which they had bought or had been assigned by the colonial government, leaving 5 million Kenyans without. Some settlers nostalgically respected Kenyan culture, like the Danish woman Karen Blixen (under the pen name Isak Dinesen), who wrote about her experiences on a plantation in Kenya in her 1937 book Out of Africa. More often, settlers were like farmer Mike Blundell, a white man featured in a Life Magazine article who had arrived as an unskilled farm apprentice but because he was white had managed to get hold of 1,200 acres of “virgin bush.” Blundell despised the local Kikuyu tribes and believed the “Kukes,” as he called them, had only “come out of the trees” in the last 50 years, and probably as a result of contact with the whites.

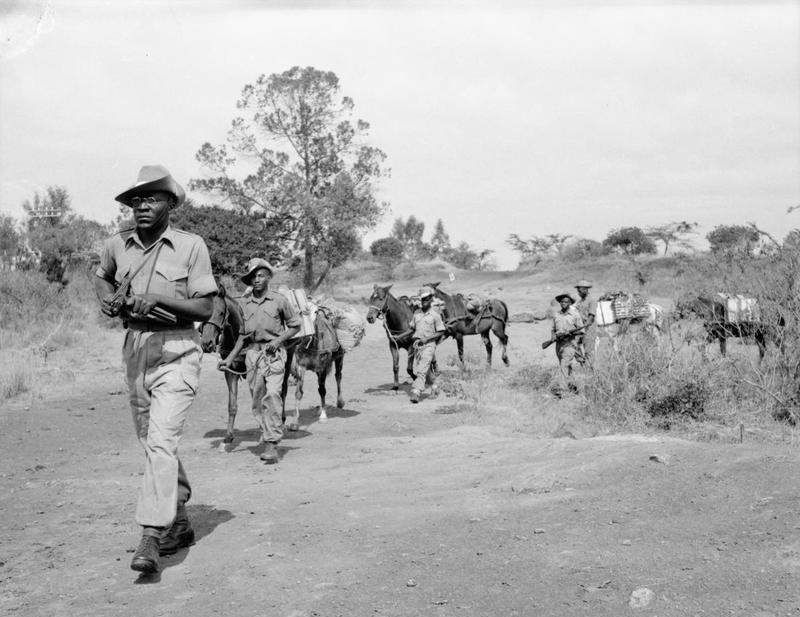

In Kenya, a resistance movement called Mau Mau began in 1952 when indigenous Black communities revolted after being restricted to reservations in their own country. After World War II, 1.25 million Kikuyu had 2,000 square miles of marginal farmland to feed themselves, while 30,000 British settlers had 12,000 square miles in the fertile hills of the Central and Rift Valleys, where they grew cash crops like coffee using native labor. The Mau Mau uprising protested this injustice, and the British colonial government responded. Declaring a state of emergency, the British moved about 450,000 Kikuyu to concentration camps, and another million were restricted to “enclosed villages.” Prisoners suspected of being Mau Mau fighters were often tortured by British troops (typically they were flogged to death, burned alive, or castrated). In June 1957, the British attorney general of the colony wrote to the governor that the mistreatment of captives was “distressingly reminiscent of conditions in Nazi Germany or Communist Russia.” He reminded the governor, “If we are going to sin, we must sin quietly.”

The uprising lasted until 1963, partly because white settlers could not easily abandon their property and go back to Britain. Power in Kenya eventually shifted from the British colonial government to a black African government, initially made up of many members of the Kenyan African National Union (KANU) that had led the resistance. Its leader, Jomo Kenyatta, became Kenya’s first indigenous prime minister from 1963 to 1964 and was president of Kenya and led the KANU party until his death in 1978. Kenyatta, like other anti-colonialist nationalist leaders—such as Gandhi and Ho Chi Minh—had traveled and studied internationally. He attended the Communist University of the Toilers of the East in Moscow as well as University College in London and the London School of Economics, although when the press mentioned him, they typically observed he had “studied in Russia.” Kenyatta was imprisoned from 1954 to 1961 for allegedly leading the rebellion and became the leader of the party and the nation when released. President Kenyatta (1964–1978) initially tried to heal the country by downplaying the atrocities of the recent war while continuing to welcome the multinational corporations that dominated the Kenyan economy during the late colonial period. However, the government also helped Black farmers buy out white landowners as part of its land reform program to return the possession of African land to Africans. He also dramatically expanded education and social support programs.

Because of Jomo Kenyata’s support of social welfare, European and American officials often accused Kenyatta of being either socialist or communist. Indeed, his ideas about land possession and social welfare were common policies of socialist and communist leaders in Africa, Asia, and Latin America during his life. However, Kenyatta himself was explicitly anti-communist and socially conservative. As a result of the perception that he favored Kikuyu over other Kenyan ethnic groups, coupled with his view that Kenya should become a right-wing single-party state and his predilections for repressing left-wing dissent, he was criticized by leftists in Kenya as dictatorial. Furthermore, he often attempted to portray socialism as a foreign idea and frequently had difficulties with other Pan-Africanist leaders because of this view. Nonetheless, his land reform policies, history of anti-imperialism, and social welfare policies convinced Pan-Africanists of his intentions. Thus, he was accepted among the Pan-Africanist leadership internationally. Furthermore, domestically, he was hailed as the Hero of the Kikuyu, the Father of the Nation of Kenya, and his son, Uhuru Kenyatta, benefitted from the historical memory of his father when he became president of Kenya in 2013.

Questions for Discussion

- Why might it be significant that revolutionaries like Kenyatta, Ho, and Gandhi were world travelers?

“French” Algeria

The British were not the only Europeans to lose their colonial empires. Although France had been conquered and occupied by Germany, after the war, the French fully expected to regain their colonial possessions in Africa and Asia and resume where they had left off. Their subject peoples in the colonies had different ideas. In Algeria, revolutionaries had been organizing to resist French imperialism since before the war. An Algerian People’s Manifesto was published in 1943. On the morning of May 8, 1945 (the day that Nazi Germany surrendered, or VE Day), a parade of about 5,000 Muslim Algerians celebrating the war’s end was met by armed French police. The police fired on the crowd, and they were met with reprisal fire from protesters. A few days later, a smaller peaceful protest by the Algerian People’s Party was violently repressed by police. Disorder broke out, and Algerian revolutionaries killed around 100 colonialists. However, the violence Algerians faced on the same day and the following days was disproportional, as between 6,000 to 30,000 were massacred at the hands of the French.

Explore More:

Watch a news reel from 1956, “France Digs in for Total War in Algeria“

The Algerians did not forget this massacre, and nearly a decade later, on November 1, 1954, Algerian guerrilla forces attacked civilian and military targets throughout the country. The National Liberation Front (FLN), encouraged by the fact that France had just lost their colony of French Indochina, called on Muslims in Algeria to join in the struggle for independence. The FLN applied guerrilla “hit and run” tactics as well as terrorism and torture of both French colonialists and Africans suspected of supporting the regime. The French were even more brutal, systemically introducing torture as a method to repress anti-imperialist protest. Furthermore, by 1956, there were more than 400,000 French troops in Algeria, who continued a long-standing French policy of committing crimes against humanity in the name of protecting imperialist interests in Algeria.

The war lasted eight years and killed over a million people. The French military lost 25,000 troops, and about 3,000 European civilians were killed. French officials estimated the Algerian death toll at 350,000, but other French and Algerian estimates range from 960,000 to 1.5 million. The United States recognized Algeria’s independence in September 1962, and the country became the 109th member of the United Nations in October. The leader of the Marxist faction of the FLN, Ahmed Ben Bella, became Algeria’s first president and nationalized much of the property in an effort to return resources back to Algerians.

Questions for Discussion

- How might the scope of European retaliation, killing about ten Africans for every European killed, have effected world public opinion?

“French” Indochina

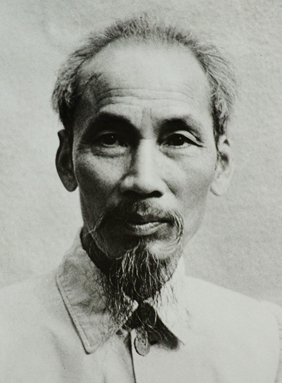

France had also expected to return to power in its colonies in French Indochina (after the Japanese retreat from Southeast Asia in 1945), but the people living there also had other ideas. Revolutionaries were led by Ho Chi Minh (1890–1969), who as a young man had studied in the Confucian tradition with his father and other major Confucian scholars, before attending a French high school and receiving a political education in France, the United States, and the Soviet Union. He worked as a kitchen helper aboard steamships in 1911 and for the next five years traveled around the world.

He visited the U.S. several times, primarily to New York City, where attended lectures by Black nationalist Marcus Garvey. He also worked in England and France between 1913 and 1919. In France, he joined a group of Vietnamese communists and nationalists in Paris. At the end of World War I, the group petitioned at the Versailles peace talks for recognition of the civil rights of Vietnamese people, citing Woodrow Wilson’s statements about self-determination in the famous “14 Points” speech. Ho Chi Minh even wrote a letter to Wilson asking for American support, but Wilson ignored him.

Rebuffed, Ho Chi Minh continued living in France in the early 1920s, meeting socialists and becoming a founding member of the French Communist Party. He then began to write articles that were noticed by intellectuals and government officials in Moscow, and he was officially invited to visit the Soviet Union. In 1923, he studied at the Communist University of the Toilers of the East in Moscow before moving to Guangzhou, China, in 1924. When Chiang Kai-shek led a brutal crackdown on communists in the Republic of China, Ho Chi Minh returned to Moscow and then moved on briefly to Thailand (then the Kingdom of Siam). In late 1929, he moved through British India to Shanghai and Hong Kong. By this time, he was becoming well known in revolutionary circles. Ho Chi Minh was arrested in Hong Kong in 1931 but escaped and returned to the Soviet Union.

In 1938, he returned to China as an advisor to the communist People’s Liberation Army. In 1941, he returned to Vietnam to lead the independence movement there. The Japanese Empire’s invasion of Southeast Asia created another opportunity for the patriots, who were aided in their resistance of the Japanese by the U.S. Office of Strategic Services (OSS), the predecessor of the CIA. At the end of World War II, Ho Chi Minh proclaimed independence for Vietnam, drawing on lines that were striking similar to the American declaration (1776). He also repeatedly petitioned President Harry S. Truman to recognize Vietnam, citing the Atlantic Charter, but Truman never responded, and British and Republic of China troops occupied the country in support of France. Vietnamese continued their decades-long anti-imperialist resistance. They organized strikes, protests, and small armed rebellions. In most cases, when violence broke out, Vietnamese revolutionaries only killed French police or troops. However, they occasionally killed French colonialists as well. In the Haiphong Massacre (November 23, 1946), the French even used a cruiser (the Suffren) to bombard the port city of Haiphong, killing 6,000 Vietnamese, the vast majority of whom were civilians, even though retaliatory fire from the Vietnamese revolutionary army, known as the Viet Minh, managed to kill 20 to 30 French troops. It was the same pattern of asymmetrical force used by empires against their subjects throughout the colonial period. For the next eight years, the Viet Minh fought campaign after campaign for independence in the First Indochina War, until the general Vo Nguyen Giap led the Viet Minh to victory at the battle of Dien Bien Phu in 1954. However, the story of Vietnamese decolonization was not even half complete; we will return to it in the next chapter when we discuss the Cold War.

Kenya, Algeria, and Vietnam were far from the only places where the imperial powers and their international allies responded violently to movements of national liberation among the colonized. In most cases, decolonization and liberation were only brought about through violent conflict, and in most cases, the empires of Britain, France, the Netherlands, Belgium, and Portugal—often backed by the United States government, along with American intelligence and weapons’ supplies—responded brutally to aims to secure independence. Why did the U.S. support such violence? As we shall see, it was part of the emergence of the aim to “contain communism” as part of Cold War policy. On the island of Madagascar in 1947, 80,000 locals were killed simply because nationalist leaders on the island clamored for self-rule. Upon the retreat of the Japanese Imperial Army from Indonesia, the Indonesian nationalists proclaimed independence in 1945 and fought four years of bloody conflict with the Dutch in a conflict that took the lives of just 8,000 Dutch troops and their allies compared to 100,000 Indonesians. Furthermore, because of the nature of the Cold War, independence did not guarantee stability—or even freedom from the economically exploitative practices of companies based in Europe and North America. In this context, the new nations of Africa and Asia sought to charter their own paths to economic stability for the majority of their population.

Questions for Discussion

- Is it significant that Ho Chi Minh worked with the OSS during World War II when he was opposing Japan?

- How many chances were there in Ho’s story where history could have turned out differently?

New Nations and Development

As part of the process of decolonization, the newly founded countries of Africa and Asia all faced the challenges of establishing borders, forming new governments, building economic self-reliance, controlling natural resources, and working toward a more just and equitable society. In previous chapters, we have seen how the new nations in Latin America had confronted similar issues since the early nineteenth century. Other older but less-industrialized countries, like the Imperial State of Iran (founded in 1925), also addressed questions of development and national sovereignty, especially as companies in Europe and North America continued to seek out “new” supplies of raw materials.

One of the major challenges faced by these new nations was the problem of borders. The administrative boundaries drawn by the European imperial powers most often did not follow the traditional boundaries established by indigenous societies, which very often more closely adhered to the natural geographical features of the landscape. We have seen that disagreements over Kashmir continue to cause tensions between India and its neighbor Pakistan, which became further complicated when India gained access to nuclear weapons in 1974 and Pakistan gained access to nuclear weapons in 1999. Furthermore, India supported the independence of East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) in the early 1970s. During the conflict, droughts coupled with the destruction of the war resulted in a famine in the very same region where British policies had worsened a famine just a generation before (during World War II).

Sub-Saharan Africa’s division by the European powers had also haphazardly thrown together peoples who wanted separate nations or who had historically not been united, while the borders had also been drawn to intentionally break up preexisting African kingdoms and empires, dividing ethnic groups across future national boundaries. As a direct consequence, two or more ethnic groups were also often pitted against one another as empires sought to secure power. Often, these conflicts between ethnic groups continued through the era of independence. Consequentially, the post-colonial violent conflicts based on ethnic loyalties have caused civil wars, and political instability oftentimes has much deeper roots. For instance, Igbo people rapidly converted to Christianity during the colonial era and often were drawn upon to support British imperialism, and tensions between Igbo, Hausa, and Yoruba communities increased. In the post-colonial period, the Yoruba people were the ethnic majority in Nigeria, and when the Igbo people tried to form a separate nation in Nigeria in 1965, the three-year civil war that followed killed thousands before Biafra was defeated. Notably, the disputed region is petroleum-rich (Nigeria leads Africa in oil production) so that even today, Igbo separatists pressure the Nigerian government, resentful that their oil wealth seems to benefit the rest of the country more than it serves them.

Such conflicts do not only result in separatist civil wars. Although no ethnic group advocates establishing their own independent state in Kenya, conflicting loyalties often spill over into political competition. As previously mentioned, Kenyan leader Jomo Kenyatta tended to favor his Kikuyu people, who were a plurality but not the ethnic majority in Kenya, during his long presidency. Resentment by the Luo and Kalenjin people led to realignments of political parties, which caused widespread violence after a contested election in 2008, with the deaths of hundreds.

Nearly all the new nations in Africa and Asia embraced various forms of democratic constitutions. But it is one thing to write a constitution and quite another to actually follow it. For instance, many new leaders critiqued the United States for failing to follow its values, arguing that the U.S. could not be called a democracy until the Voting Rights Act was passed in 1965, and that the very existence of continued discriminatory treatment of Black and Indigenous Americans after 1965 called into question the legitimacy of American claims about democracy. Some African states also argued in favor of having single-party states under their new constitutions. In Tanzania, when Pan-Africanist and anti-colonial revolutionary Julius Nyerere was critiqued for establishing a single-party state, he responded, “The United States is also a one-party state but, with typical American extravagance, they have two of them.”

Like older republics in North, Central, and South America—as well as Europe—new nations in Africa and Asia often saw periods of authoritarian rule. The cause for the frequency of this occurrence has been located by political scientists in the fact that many new political leaders had been military commanders in revolutionary armies. Thus, they were more likely to attempt to regulate their societies in keeping with the military culture they were previously familiar with—that is, in an authoritarian fashion. However, in the new African and Asian nations, the record of these leaders was also substantially mixed. For example, while Thomas Sankara of Burkina Faso was criticized by Amnesty International for his treatment of corrupt public officials and execution of political rivals through swift trials conducted by Popular Revolutionary Tribunals, he also led the unprecedented expansion of women’s rights in the country.

Thomas Sankara’s government in Burkina Faso banned female genital mutilation, forced marriages, and polygamy. They also appointed women to high positions in government for the first time, expanded access to education, and encouraged women to become financially independent. All of Sankara’s policies supporting women’s rights were in keeping with his revolutionary socialist platform, the very same platform that led the government of France to back the coup d’etat that led to Sankara’s assassination. In the context of the Cold War, the coup led to anti-socialist stances in Burkina Faso that were quite like Fascist positions in interwar Europe, following a pattern that was unfolding elsewhere in Africa and Asia, as well as across Latin America. However, the pattern was not universal. There were some countries, such as India, where the politics of new societies attempted to take a course of center-left democratic socialism in the context of decolonization.

As previously mentioned, the new nations of India and Pakistan (Pakistan and Bangladesh) continued to struggle with stability as conflicts exasperated by colonial policies continued. India’s head of state, Jawaharlal Nehru, embraced a center-left position as a democratic socialist, meaning that he supported the socialist policies of economic reforms and promoted the establishment of social welfare programs, as well as the democratic reforms of establishing a multi-party parliamentary democracy. As a result of Nehru’s leadership, the Congress Party was a major force in Indian politics until the 1990s, and India was often heralded at the end of the 20th century as the world’s largest democracy, although it was also the world’s second-largest officially socialist state. However, far-right elements of Indian politics, advocates of the Hindutva (“Hindu nationalism” or “Hindu fascism”) ideology, consistently threatened the stability of the state in the 20th century. As those very same elements came to control the right wing of Indian politics during the early 20th century, the erosion of the judiciary and transformation of many individual states within India into de facto single-party states, coupled with outbreaks of state-sanctioned anti-Muslim violence, was part of a broader pattern of democratic backsliding worldwide.

The prominence of Nehru’s leadership in India also established a political family that might remind students familiar with American history of the Kennedys or the Bush family. After Prime Minster Jawaharlal Nehru died of natural causes in 1964, his daughter, Indira Gandhi (of no relation to Mahatma Gandhi’s family), rose to prominence. She became prime minister twice (1966–1977 and 1980–1984) and her son, Rajiv Gandhi, was prime minister from 1984 to 1989. Their dedication to the principles of democratic socialism brought a degree of stability to the country, although India was not free from problems resulting from colonial-era divisions.

The Sikh population of South Asia had been divided by the partition of India and Pakistan. As they practiced a religion that blended elements of both Islam and Hinduism, one might suspect they would be welcome in both new states. However, Sikhs had also frequently been recruited to serve in the British Imperial Army, and were, in effect, welcome in neither. Sikh revolutionary sentiments spread during Indira Gandhi’s second term as prime minister, and elements of her cabinet advocated for a strong hand in response. In direct reprisal for the repressive treatment of Sikhs, Indira Gandhi was assassinated by two of her own guard, who were also members of the Sikh community. In Southern India, an ethnic Tamil insurgency movement, popularly known as the Tamil Tigers, were founded in 1976, toward the end of Indira Gandhi’s first term as prime minister. In 1991, the Tamil separatists assassinated her son, Rajiv Gandhi.

Despite these political crises and others—including an ongoing border conflict with the People’s Republic of China and the annexation of the Himalayan Kingdom of Sikkim (1975)—elections continued. Opposition coalitions formed and reformed, often including odd alliances of right- and left-wing parties. In the south of India, the Communist Party established a decades-long successful electoral platform in the state of Kerala. Meanwhile, in the central and northern portions of the country, social conservativism and Hindu nationalism re-emerged in popularity during the early years of the 21st century.

Did you know?

Hindu nationalism, or Hindutva, is a political ideology advocating for national identity based on Hindu identity. It typically excludes minority religious groups, especially Muslims, from inclusion in Indian society. Manifestations of Hindutva ideology range from right wing to far right wing and militant extremist. Hindutva has also been called “Hindu fascism,” as the leaders of the Hindutva movement were indeed close allies of European fascists in the middle of the 20th century. The RSS is a key Hindutva organization, and members of the RSS assassinated Mahatma Gandhi. The Hindutva far-right nationalist politicians of the Bharatiya Janata Party (f. 1980) had their first term in government as part of the National Democratic Alliance (NDA) from 1998 to 2004. However, although the NDA was led by the BJP, the inclusion of a big tent of opposition parties—including Tamil nationalists, center-left socialists, and some smaller center-right parties—effectively prevented them from enacting the more radical Hindu nationalist platform of the far-right politicians in the BJP. The trend would change as the BJP won a resounding electoral victory with Prime Minister Narendra Modi securing a 10% lead over the fourth generation of Jawaharlal Nehru’s political dynasty (and Rajiv’s son): Harvard and Cambridge educated Rahul Gandhi. Unable to stave off the growth of Hindutva nationalism in India, he resigned from head of the INC in 2019, and his mother, Sonia Gandhi, is now head of the party.

Unlike in Nehru’s India, Pakistan did not benefit from an initial long premiership by its founding father, Muhammad Ali Jinnah, who died barely a year after independence of tuberculosis and lung cancer. Internal and international crises led to repeated interventions by the Pakistani military into national government. The military rose to prominence in part due to the role that Pakistan played as a military ally of the United States in Asia. Although the Oxford-educated socialist reformer Zulfikar Ali Bhutto attempted to decrease the power of the military in the late 1970s, he was deposed in a military coup led by General Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq. Zulfikar Ali Bhutto was then tried and sentenced to death by hanging by the supreme court of Pakistan, while the general ruled as president of the country for the next decade, ushering in a period of right-wing religious and military rule and an even closer relationship with the United States in the context of the Cold War.

After General Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq died in a plane crash, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto’s daughter was elected to her first term as prime minister of Pakistan in 1988. She would serve twice as head of state, leading attempts at substantial political reforms, although her progress was stifled by the military and she went into self-imposed exile from 1998 to 2007. Upon return, she faced an almost immediate assassination attempt in a bombing that killed 149 people. She may have faced additional assassination attempts, but a second known assassination attempt resulted in her death, although the direct cause of death (either from gunshot wounds or from the shrapnel of a bomb that exploded shortly thereafter) is not known. As a direct result of this tumultuous history, the 2013 Pakistani elections were the first time one democratically elected government peacefully replaced another, when Benazir Bhutto’s husband, Asif Ali Zardari of the left wing Pakistan People’s Party, handed over the reins of government to center-right leader of the Pakistan Muslim League Party, Mamnoon Hussain. But even today, the military plays an independent, often secretive role in Pakistan, especially in foreign policy, in part because of the long-standing and close relations with the U.S. military, which continued to provide the Pakistani military with hundreds of millions of dollars of military aid per year in the 21st century, totaling $5.4 billion of arms sales alone between 2002 and 2014.

The Question of Development

In the process of decolonization, the new nations were faced with the question of how to develop their economies. Many governments were inspired by the rapid growth of the Soviet Union achieved by the Central Planning Committee’s “Five Year Plans,” which first began in 1921—during the era when Lenin was the founding leader of the Soviet Union. Whether or not new nations aligned themselves with the Soviet Union (and officially, most did not), new governments tended to view central planning of at least a few key sectors of their economies as necessary to achieve self-reliance. Others were more readily coerced by capital investment and simply attempted to reformulate the balance of their economies while still providing the governments of Western Europe and the North Atlantic with substantial imports of raw materials. However, there were not simply two models of development. Most states attempted to adopt some methods of centralized planning with a certain amount of privatization and the acceptance that the principles of supply and demand should drive industrial production. These economies would be called “mixed economies.”

One of the primary thinkers of non-aligned economics in the middle of the 20th century was the Argentinian economist Raúl Prebisch. Prebisch criticized the American and European economists, such as Talcott Parsons, for creating policies that left new nations, but especially those in Latin America, essentially bankrupt and intentionally debt burdened. Based on his observations of the structure of global economics after the Second World War, he developed a theory called “dependency theory.” According to Prebisch’s theory, the world was essentially divided into industrialized “core” and an underdeveloped “periphery.” After the Second World War, the purchasing power of the “core” nations (such as France, England, and the United States) was accelerating. They were able to purchase more and more raw materials for a cheaper and cheaper relative price. On the other hand, the ability of “periphery” countries to import industrial products was decelerating. In response, the idea was to replace these imports with locally produced industrial products while also reducing the amount of exports available to former imperial powers, driving up their cost—and therefore revenue-earning potential—in the international marketplace.

By 1964, Prebisch was so renowned internationally that he became the founding secretary general of the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). His theories were taught in many international schools and remained the dominant economic theories of Chilean institutions up through the 1970s (at which point a coup d’etat ushered in a neo-authoritarian order in Chile). The position of UNCTAD was, officially, that the World Bank and the U.S.-dominated International Monetary Fund (IMF) were ill-conceived and not capable of acting in the interests of developing nations. Typical UNCTAD agreements aimed to stabilize international economic policies, thus preventing recessions, depressions, and other economic woes such as famines. For instance, the 1968 conference held in New Delhi established an agreement to stabilize global sugar prices. Efforts to improve the stability of commodities pricing were additionally bolstered by the Green Revolution.

Did you know?

The IMF & World Bank

In recent decades, a leader in the political push for privatization has been the International Monetary Fund (IMF), first established at the July 1944 conference at the Mount Washington Hotel in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire, mentioned earlier. Even before the war ended, forty-four allied nations sent 730 delegates to establish what would become a global system for regulating international balances of commercial payments and securing what they hoped would be financial stability for the post-war world. Initially, they were mainly thinking of creating institutions and policies that would both rebuild war-torn Europe and Asia and prevent the hyperinflation and Great Depression that led to so much instability between the wars.

There were two architects of the meeting and the global financial plan that came from it. John Maynard Keynes was the British economist who had pioneered the “demand-side” economic theory that people like U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt had adopted to confront the Great Depression. Keynes’s claim was that by spending money, the federal government could jump-start the economy, create jobs, and put the money in people’s pockets that would enable them to buy consumer products. This plan was temporarily derailed by war production and rationing, so it is unclear to many economists that Keynes was right and that deficit spending and government borrowing was the key to ending the Depression. At the time of the Bretton Woods Conference, Keynes was the chief advisor to the chancellor of the exchequer in Britain. The American, Harry Dexter White, worked closely with Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau Jr. White dominated the conference, and although he considered himself a Keynesian, he vetoed Keynes’s proposal for the International Clearing Union (ICU), a central bank with its own currency, the “bancor.” White opposed the ICU and instead proposed an International Stabilization Fund that would help debtor nations maintain their balance of trade. This grew into the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD), which became the World Bank. The U.S.’s goal was to promote international development but also to help establish markets for American manufactures now that the war effort had greatly increased U.S. manufacturing capacity.

Another reason the U.S. rejected the ICU and the “bancor” was to protect the leading position of the dollar in the world economy. Since the U.S. had the strongest economy in the world at the end of World War II, they also dictated the trade provisions agreed to at the conference. The major provisions of the agreement were a foreign exchange system with the U.S. dollar as its base currency, along with a pledge by members to convert their currency to gold for trade-related demands. Countries were required to adopt the gold standard and were not allowed to alter their currency’s exchange rate by more than 10%. This would prevent debtor nations from escaping their obligations to creditors by simply inflating their currencies. Finally, all members had to pitch in to the new bank’s assets, although the U.S. put up most of the money.

Bretton Woods also drafted a set of trade-related recommendations, and an International Trade Organization (ITO) was proposed with a goal of reducing tariffs. The United States Senate, however, was not interested in ceding its authority over tariffs to a new international organization and did not ratify the ITO’s charter. The less aggressive General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) was adopted in its place. We will discuss it when we cover globalization.

Bretton Woods created the International Monetary Fund (IMF), which lends money to distressed economies suffering from hyperinflation or other financial chaos and, as a condition for credit, stipulates how a borrower country should reorganize government spending and finance. The IMF was designed to oversee the international monetary and financial systems and to monitor member nations. The U.S. undermined this mission when it went off the gold standard in 1971. Inflationary government spending on both the war in Viet Nam and the War on Poverty begun by Lyndon Johnson and a worsening balance of trade led the Nixon administration to fear that foreign holders of dollars would demand conversion to gold, which would rapidly wipe out the U.S. gold reserves, held in federal bullion depositories such as Fort Knox. Nixon’s unilateral decision was ratified by Congress in 1978. By the end of the 1970s, no major currency was convertible for gold. Although the dollar is no longer redeemable in gold, the United States continues to maintain a gold reserve of over 8.1 metric tons, more than half of it stored at Fort Knox in Kentucky. The next largest national gold reserve, roughly 3.3 metric tons, belongs to Germany.

Losing their original reasons for existence, the IMF and World Bank were forced to adapt. Rather than enforcing convertibility, the IMF began using its ability to loan interest-free development money to debtor nations as a way to intervene in and direct the economic policies of the borrowers. The IMF’s stated aim was to avoid or mitigate financial crises using the “conditionality” of their loans. The IMF now analyses nations’ economic policies and offers “advice” that must be taken in order to receive IMF loans.

The changes the IMF and the World Bank require are called structural adjustment programs. They typically include deregulation, privatization, and removal of trade barriers. All of these measures have been criticized by debtor nations as being more beneficial for the lenders in developed industrialized nations than for borrowers in the developing world. Other structural adjustments can include reducing trade deficits through currency devaluation, austerity programs to decrease budget deficits, eliminating social welfare programs, cutting public services, focusing economic output on resource extraction, and attracting foreign direct investment. This current bundle of structural adjustment programs is known as the Washington Consensus and is associated with neoliberalism or market fundamentalism, which we will discuss in a later chapter. Even in its more modest formulation, IMF policy is designed to liberalize trade, deregulate and privatize industries, and protect property rights above all other concerns.

Questions for Discussion

- How did Stalin’s lies about the success of the Five Year Plans affect the decisions of newly decolonized nations?

- In what ways did the problems of borders and religious differences continue to plague the new nations?

The Green Revolution

The explosive improvement of agricultural yields throughout the world known as the Green Revolution began in the 1960s in a research station on the edge of the Mexican desert. The scientist most associated with these advances is Norman Borlaug, an agronomist who developed a disease-resistant strain or dwarf wheat that increased yields of the grain worldwide, especially in developing nations facing high population growth and threat of famine. Borlaug (1914–2009) grew up on a 106-acre Iowa farm and attended the University of Minnesota in the 1930s. Borlaug’s education included a stint in the Civilian Conservation Corps during the Great Depression. He later remembered that seeing the effect of hunger on people in America “left scars” on him and motivated him to try to solve the problems of supplying food to a growing world population. Borlaug continued at the U of M after graduation, eventually earning a Ph.D. in plant pathology and genetics in 1942. Borlaug then went to work as a microbiologist at DuPont. After a couple of years with DuPont, he joined the Cooperative Wheat Research Production Program, a joint venture of the Rockefeller Foundation and the Mexican Ministry of Agriculture.

Borlaug found that local Mexican farmers resisted planting wheat because a fungus called stem rust reduced their yields so much, they couldn’t make a living. A related problem with wheat farming in Mexico was that the plants grew too tall when heavily fertilized and then “lodged,” or fell over, prior to harvest. Borlaug and his team bred a new strain of dwarf wheat that would not grow too tall when fertilized and that also resisted rust. The process took ten years and over 6,000 cross-breeding experiments between different types of wheat. The new wheat had the additional advantage of being able to be planted twice per year. Although it took Borlaug a while to convince local farmers to try his new hybrid, they could see his fields and were finally convinced. Between 1950 and 2000, Mexican wheat yields increased between 400% and 500%.

In the 1960s, as the program was becoming successful in Mexico, it was exported to India, which was facing famine. American farmers shipped a fifth of their wheat production to India in 1966 and 1967. The Indian situation seemed dire, especially since India’s population crossed the 500-million mark in 1966 and was expected to grow by another 200 million by 1980. The prediction was accurate: India crossed 700 million in the early months of 1981, on its way to a current level of 1.38 billion. India imported 18,000 tons of Borlaug’s seed wheat in 1966. Wheat yields increased from 12.3 million tons in 1965 to 20.1 million tons in 1970. By 1974, India was self-sufficient in all cereal grains, and the USAID (U.S. Agency for International Development) began calling Borlaug’s work a Green Revolution. Since the 1960s, India’s food production has increased faster than population growth. By 2000, India was producing 76.4 million tons of wheat.

India’s improved crop yields, driven by Borlaug’s improved wheat, have made it a net exporter of wheat. India began exporting wheat regularly in the 1970s and since 1980 has exported wheat every year except three. The nation’s exceptional agricultural turnaround was made possible by Borlaug’s new wheat, but also by the extensive use of fertilizer, irrigation, and machinery. The improved crop and techniques have prevented up to 100 million acres of virgin land from being converted to farmland. This savings amounts to 13.6% of India’s land, or about the area of California. Borlaug predicted that as world population continued to rise, only new crops and improved farming techniques would save the world’s remaining forests and uncultivated lands.

Although the Green Revolution has undoubtedly saved lives and allowed populations in India to increase dramatically, Borlaug and the Green Revolution have been criticized for bringing capital- and energy-intensive American and Canadian agricultural techniques to regions of the world that had once relied on subsistence farming. American- and Canadian-style farming tends to reward large-scale operators and often provides even greater rewards to manufacturers of agrochemicals and machinery. Widening social inequality and expanding farmer debt has led to issues like the suicide crisis of India. Public intellectuals like Dr. Vandana Shiva have argued that 80% of the world’s population is actually fed by the produce of subsistence farmers rather than the industrialized agriculture highlighted in the Green Revolution. She supports biodiversity, organic farming, and farmer’s rights.

Dr. Shiva has also been an influential critic of genetically modified organisms (GMOs) as well as the use of chemical fertilizers and pesticides. Although Borlaug’s dwarf wheat was not produced by the very advanced forms of genetic manipulations currently available to produce GMO crops—and similar interventions are precisely how broccoli, Brussel sprouts, kale, and cabbage were all derived from wild mustard—some still resent it as a human intrusion on nature’s processes. Dr. Shiva has also highlighted the impacts of pollution and the loss of indigenous ways of farming. Her goal is to point out that humans and the earth are one, and solutions need to work in harmony, a notion that integrally involves a better understanding of climate change and the pending Anthropocene, as we discuss in the next two chapters.

Question for Discussion

- What were the pros and cons of the Green Revolution?

Media Attributions

- American_military_personnel_gather_in_Paris_to_celebrate_the_Japanese_surrender © Office of the Chief Signal Officer is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Winston_Churchill_waves_to_crowds_in_Whitehall_i n_London_as_they_celebrate_VE_Day,_8_May_1945._H41849 © Major W. G. Horton is licensed under a Public Domain license

- The_Fighting_Filipinos_-_NARA_-_534127 © National Archives and Records Administration is licensed under a Public Domain license

- INDIAN_TROOPS_IN_BURMA,_1944 © No 9 Army Film & Photographic Unit is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Dead_or_dying_children_on_a_Calcutta_street_(The_Statesman_22_August_1943) © Statesman is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Gandhi_and_Nehru_in_1946 © Dave Davis is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Partition_of_India © McMullen is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Zina_Dizengoff_Circle_in_the_1940s © בישראל ובניה תכנון is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Menachem_Begin_2 © MSGT DENHAM is licensed under a Public Domain license

- 2c0ee9f4f58a2d9232f737498250c8e3 © Visualizing Palestine is licensed under a CC BY-NC-ND (Attribution NonCommercial NoDerivatives) license

- Jomo_Kenyatta_1966-06-15 © Government Press Office is licensed under a Public Domain license

- KAR_Mau_Mau © Ministry of Defence is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Semaine_des_barricades_Alger_1960_Haute_Qualité © Christophe Marcheux is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Ho_Chi_Minh_1946 © Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Ho_Chi_Minh_(third_from_left_standing)_and_the_ OSS_in_1945 © U.S. Army is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Pahalgam_Valley © KennyOMG is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- A woman in Burkina Faso © Anton Osberg is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Indira_Gandhi,_Jawaharlal_Nehru,_Rajiv_Gandhi_an d_Sanjay_Gandhi © Royroydeb is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Wheat-haHula-ISRAEL2 © CarolSpears is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Wheat_yields_in_Least_Developed_Countries.svg © Grendelkhan is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Dr. Vandana Shiva © Augustus Binu is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license