12 Globalization

The Era of Globalization

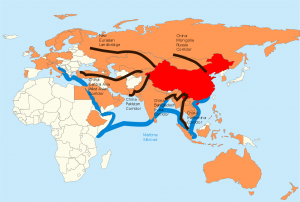

The era of world history from the late 1980s through the 2010s—in other terms, the end of the Cold War through contemporary history—is often called the “era of globalization.” Yet, what does this word, “globalization,” mean? To “globalize” or “to become global” implies that there are connections that are built that go beyond the boundaries of nation-states to form regional and supra-regional organizations. Historians often debate when globalization began. For example, the connections of the land-and-maritime Silk Road has sometimes been called “the first globalization” because the Silk Road connected East Asia to Southeast Asia, to South Asia and East Africa via sea-based trading networks, along with East Asia to South Asia, Central Asia, Western Asia, and the Mediterranean via land-based trading networks. These networks, after all, were travelled by the Chinese Muslim Ming dynasty–era admiral Zheng He in the 15th century as he sailed from China to Southeast Asia, to India, to East Africa and the Arabian Peninsula. The “second globalization” began in the 1980s and 1990s with a dramatic increase in the connectivity of global trade networks.

Maybe the contemporary era of globalization began in the 1940s through the 1950s, when the formulation of the United Nations created a new global governance structure that was headed by leaders from Brazil, Argentina, the Philippines, Iran, and Mexico and, in 1953, by Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit of India, who became not only the first female president of the U.N. General Assembly but also the first leader affiliated with a country that would become the Non-Aligned Movement. Indeed, Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit’s brother Jawaharlal Nehru was also the head of state in India, while her niece Indira Gandhi became the first female prime minister of that country. Maybe, however, communications technology is the key. While Welsh computer scientists Donald Davies and Polish American engineer Paul Baran both conceived of distributed communications networks that would send data across these networks in message blocks in the 1960s, the Soviet Union had reached a turning point as the Altai mobile telephone system—based on a radio-telephone model—became available in most major cities by 1965. Nonetheless, most historians would agree that by the end of the 1980s and the early 1990s, some combination of international economics, global governance structures, and rapid advances in communications technology combined to create a new era of globalization.

While the era of globalization is typically thought of as changes in economics, governance, and technology, we should be reminded that global structures can impact every aspect of our everyday lives, from the climate we live in to the health of our loved ones. An early reminder of this in the 20th century was the “Spanish flu of 1918,” which historians now think lasted from approximately 1916 to 1920 in various waves across the world. The evidence suggests that one factor in the prolonged pandemic was simply public failures, often concentrated in cities, to follow public health recommendations suggested by medical professionals. Yet, when the World Health Organization (WHO) was founded in 1948, based upon the ideas of Szeming Sze (Republic of China), along with his Norwegian and Brazilian colleagues, they were also building on the French precedent of the International Sanitary Conferences (ISC, 1851–1937) that had sought to mitigate the global spread of plague, cholera, and yellow fever. Enormously successful long-term campaigns to eradicate smallpox in major portions of the world using vaccines and the disease surveillance method began in 1967. In 1975, the WHO launched a Special Program for Research and Training in Tropic Diseases to combat tuberculosis (TB), onchocerciasis (river blindness), and malaria. By 1986, the WHO had launched a global program to combat the HIV/AIDS crisis during an era when most Americans were still in denial that there was even such a crisis.

By the 1990s, through these campaigns and related health programs, the WHO had dramatically reduced the spread of communicable diseases. The WHO had eradicated smallpox and rinderpest while dramatically reducing instances of polio, tetanus, hepatitis, rubella, measles, whooping cough, rotavirus, mumps, and diphtheria. They had also reduced child poverty. Nonetheless, as an organization, some of their efforts were limited by ongoing zones of conflict and refugee movements. As was mentioned in the previous chapter, there were ongoing liberation struggles during the Cold War era. As discussed in the last chapter, none of these struggles were proxy conflicts, as they were instead conflicts over the trajectories of new nations. Yet, the United States, the Soviet Union, and the People’s Republic of China often backed sides of the conflict, deepening divisions. Even after the dissolution of the Soviet Union, these trajectories continued. For example, Russia sought to re-expand influence through the Russo-Chechen Wars, the Five-Days War, the Syrian Civil War, and the Ukrainian War. In the case of the People’s Republic of China, a conflict that began in the 1960s in Xinjiang transformed throughout the decades but remains central to the claims of the genocide of the Muslim Turkic minority Uyghur population that have been levied against the government of the PRC in the 21st century. In the case of the United States, ongoing intervention in Latin American politics that started long before the Cold War continued into the 21st century, not to mention the wars in Libya, Somalia, Syria, Afghanistan, and Iraq. At the same time, the international community attempted to act as a peacekeeping force, eventually seeking a path to peacemaking, or ending conflicts, and peace building—that is, building the social institutions in post-conflict societies necessary to prevent future conflict.

Although the history of United Nations peacekeeping forces is routed in the Cold War era, the practicality of international governance prevented them from being used often. To explain, U.N.-backed peacekeeping missions must be approved by the Security Council, meaning that the five permanent members of the Security Council (Russia, the PRC, the United States, France, and the United Kingdom) would have to agree on a mission. After 1991, however, there was a substantial shift in U.N. peacekeeping missions. They became, for a time, much more common. Missions to El Salvador and Mozambique were viewed as widely successful. In Cambodia, peacekeeping forces backed the establishment of the United Nations Transitional Authority in Cambodia (UNTAC), which established a parallel system of governance in 1992 to 1993 that brought an end to the Cambodian Civil War. However, U.N. officials were not always informed of situations on the ground. For example, U.N. diplomat Benny Widyono (d. 2019) often recounted of his experience, arriving in Cambodia and being told he was to stand in as governor of a province, although the first person he met on the ground was a stand-in Cambodian governor of the same province. They had been intended to work as partners, but neither had been informed of this detail. Nonetheless, the role of the United Nations in bringing peace to Cambodia grew to be viewed as a success, as did the U.N. role in the negotiations to end the Eritrea-Ethiopia conflict and secure Eritrean independence in northern Africa in 1993.

The 1990s also saw major international conflicts where the U.N. peacekeeping forces were not able to achieve an end to conflict, and conflicts have since re-emerged or deepened, such as with the case of Somalia. In part, these operations suffered from a lack of personnel and lacked necessary international backing (such as from the United States, Russia, or the PRC) to issue real mandates. Further examples tended, therefore, to be viewed as failures, especially in the context of the case of the 1994 Rwandan genocide and the 1995 massacre in Srebrenica and Bosnia and Herzegovina—areas formerly associated with Yugoslavia, which had broken up in 1992. As was the case of the militaries of major members of the Security Council, U.N. peacekeeping forces also came under criticism for incidents involving sexual abuse, murder, and extortion/theft, along with other crimes committed by U.N.-aligned soldiers. This was the case with the peacekeeping missions involved in the Second Congo War, the Somali Civil War, the Eritrean-Ethiopian War, along with cases in Burundi, Rwanda, Liberia, Sudan, Côte d’Ivoire, Haiti, and Kosovo. Hence, by the 2010s, the United Nations took very serious steps toward reforming its peacekeeping forces, following the trajectory of criticism brought forward by the Brahimi Report (released in 2000).

As of this writing, current significant peacekeeping missions are ongoing in the Western Sahara Conflict, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Sudan and South Sudan, the Northern Mali Conflict, the Kashmir Conflict (India and Pakistan), the Arab-Palestinian-Israeli Conflict (ongoing since 1948), the Cyprus dispute (involving Cyprus and Northern Cyprus), and the Kosovo War (involving Kosovo and Serbia). In many cases, the Security Council forces collaborate with regional governance structures, such as the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), most of which emerged through regional trade blocs that were organized during and after the Cold War. For example, in the case of ECOWAS, the original charter was established by the Treaty of Lagos (Nigeria) in 1975, but the current organization is primarily governed under a revised trade agreement that was negotiated in 1993. ECOWAS is also a bit of an outlier in the case of these regional trade organizations, as they have their own security forces, which parallel the U.N. peacekeeping forces. Yet, quite similar to other regional trade groups, they have formed various economic agreements across member nation-states. For example, within ECOWAS, the West African Economic and Monetary Union (UEMOA) is a group of countries that were predominantly colonized by France and thus retain certain cultural and economic commonalities as a legacy of that colonial experience. Within UEMOA, the CFA Franc was adopted as a common currency among the member states in 1994. Guinea-Bissau (a former Portuguese colony) would also join the UEMOA in 1997. A similar West African Monetary Zone (WAMZ) would be formed in 2000, which planned to introduce a common currency among Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Nigeria, and Sierra Leone, called the “Eco.” The Eco, by design, would rival the CFA Franc.

A significant part of the linchpin to the ECOWAS and WAMZ organizations is the role that oil plays in the Nigerian economy. Nigeria experienced an oil boom in the 1970s, and the country joined the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC, f. 1960, Baghdad) in 1971. During the same decade, attempts to restrict oil production spiked petroleum prices, with far-reaching crises for the global economies, yet also meaning that the wealth of OPEC states’ holdings crashed when they came back down. By the 1980s, OPEC set production targets, and thus the period between 1990 and 2003 is typically described as a period of ample supply with modest disruptions. However, the environmental consequences of major oil production from OPEC member states, along with Russia, the United States, and the PRC, and former colonial oil companies (Dutch-Shell, for example), had enormous consequences, as we shall explore in the next chapter. By 2003, the U.S. wars in the name of the “War on Terror”—although the U.S. invasion of Iraq had nothing to do with terrorism whatsoever—introduced increased volatility into the OPEC market. Although OPEC is famous for the inclusion of countries such as Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Libya, Nigeria, Saudi Arabia, Algeria, the United Arab Emirates, and Venezuela as member states, the organization has recently expanded through the inclusion of Angola (2007–), Equatorial Guinea (2017–), and the Republic of the Congo (2018–).

Oil economies—the United States, Russia, the People’s Republic of China, and OPEC member states included—became major drivers of global economic trends during the 1990s. As we saw in the previous chapter, in 1938, Mexican President Lázaro Cárdenas nationalized production in Mexico using the power of the 1917 constitution of the Mexican Revolution to do so. The key wording stated that the government had ownership rights to the subsoil assets of all of Mexico, which thus allowed President Cárdenas to form the government-owned oil company Pemex. American and Allied reliance on Mexican oil during WWII increased the profit margins for Pemex, a trend that would continue with the rebuilding of Germany and Japan, right through the Cold War, with the Brazilian company Petrobras becoming the only substantial regional competitor to not be based in the United States. Petrobras had been created under Getúlio Vargas in 1953, under the understanding that the government controlled all rights to oil production in the country. By 1994, Petrobras had put the world’s largest oil platform into service, the Petrobras 36. However, in 1997, the Brazilian government introduced new laws to create space for private companies to create private ownership over portions of Brazil’s oil fields. Such privatization of previously publicly owned resources was broadly characteristic of the neoliberal economic policies that had first been foisted upon the Chilean people under the dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet, but also more broadly across the region from the 1970s through the 1980s.

The privatization of economies across Asia, Eastern Europe, Africa, Latin America, and the Caribbean from the 1980s through the 1990s was broadly hailed as producing positive results. True believers argued privatization was part of an economic miracle of growth and production. However, they failed to ascertain the reality of growing economic inequality, environmental destruction, and political instability introduced as a direct result of these economic policies. Political consequences could be far reaching, such as in the wake of the Asian Financial Crisis of 1997, which crushed the economies of South Korea, Thailand, the Philippines, Malaysia, Singapore, and Indonesia. Most notably, the financial crisis resulted in the resignation of American-backed dictator Suharto in Indonesia, along with Prime Minister General Chavalit Yongchaiyudh in Thailand. In the OPEC member state of Venezuela, the presidency of Carlos Andrés Pérez resulted in the introduction of similar neoliberal privatization policies and austerity. When these economic policies failed and there were massive protests of the government, President Pérez brought the military in to repress the protesters. However, one officer did not participate, as he had a case of the chickenpox. His name: Hugo Rafael Chávez Frías.

Although Hugo Chávez then went on to plot a failed golpe de estado against the government, he was later pardoned and gained political prominence from critiquing the failures of neoliberal economic policies. He formulated a socialist party based on a combination of Marxist-Leninism and revolutionary Latin American traditions that he called “Bolivarianism” in 1997. In the 1998 presidential election, the political party Movement for the Fifth Republic (MVR) gained enormous popularity and brought him to the presidency with 56% of the vote. Although always contested, he won elections again and again, with nearly 60% of the vote in 2000, 62.8% of the vote in 2006, and 55.1% of the vote in 2012, although he died from cancer in 2013. The so-called Bolivarian Revolution aimed to provide food, housing, healthcare, and education as basic rights to the people of Venezuela. From 2003 through 2007, financed in part by oil profits, there were clear indicators that poverty decreased, literacy increased, average quality of life increased, and income inequality in the country decreased. However, relations with the United States disintegrated throughout and after Chávez’s presidency, even as Chávez directed the Venezuelan government to give the United States tons of food, water, and a million barrels of oil to the victims of Hurricane Katrina in 2005. He would also give free oil to the poor in Europe and the United States, including First Nations of Indigenous Peoples living in Alaska, Montana, and South Dakota via Citgo-Petroleum, the Venezuelan government’s Houston, Texas–based oil subsidiary.

Chávez’s political rise toward the end of the 1990s occurred amid dramatic changes across the continent. Neoliberal economic policies had been heralded as an economic miracle. Yet, cuts to social welfare spending, foreign investment, and the privatization of formerly public-sector markets left the region with high inflation, unemployment, and dramatically ever-increasing wealth gaps. More and more people worked in the informal economy, suffered economic insecurity, and suffered from housing insecurity. Although they were mostly not Marxist-Leninists, a substantial portion of Latin American political parties were center-left democratic socialist parties that began to increase in popularity. Seeking to alleviate the social conditions, Cristina Fernández de Kirchner (Venezuela, 1999), Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (Brazil, 2003), and Evo Morales (Bolivia, 2006) became significant leaders in the so-called Pink Tide of Latin American left and center-left political leaders who controlled almost all of the heads of government in South America, with the notable exception of Colombia and Chile, by 2011. However, Chile had center-left heads of state from 2000 to 2010, 2014 to 2018, and again as of Gabriel Boric’s ascension to office on March 11, 2022. High prices for commodities fueled the social programs of the Pink Tide, lowering economic inequality and creating increased rights for LGBTQIA+ populations across the continent, along with increased recognition of the rights of Indigenous Peoples. The Pink Tide thus marks a significant Latin American political response to the neoliberal economic policies that were tested in Chile during the Cold War and heralded across the region as producing economic miracles in the 2000s. However, amid the rise of Gabriel Boric’s campaign, variations on the popular slogan “Neoliberalism was born and will die in Chile” (El neoliberalismo nace y muere en Chile) have become quite prominent.

Questions for Discussion

- What was Venezuela’s motivation for nationalizing its oil and then giving some away to poor people in the U.S.?

At the end of the Cold War, there was an assumption, especially in the United States, that capitalism had defeated communism. This view misrepresented the reality of the history of the Cold War, as we discussed in the last chapter. Yet, it also misrepresented the market forces of the post–Cold War era. Already in this chapter, we have seen how the market forces of neoliberalism in Latin America were contested by an emergence of popular economic answers to inequalities that were rooted in either socialism, democratic socialism, or social democracy. Similarly, within the former Soviet Republics, a political contestation emerged. Like Latin America or Germany, the right-wing, socially conservative political parties in Eastern Europe tended to refer to themselves as “Christian Democrats.” Initially, these parties tended to support classical liberal economics, advocating very strictly for privatization and free-market economies, coupled with increased political freedoms. However, they began to drift rightward quickly. First, corruption became widespread, and critics referred to them as kleptocracies—countries where political leadership appropriated the wealth of the state, either through misappropriation of funds or outright embezzlement. Next, they tended to adopt neoliberal economic policies, used increasingly anti-immigrant rhetoric, and clamped down on political freedoms. By the middle of the 2010s, these formerly center-right political parties were mostly led by right-wing ultraconservatives or, in many cases, far-right authoritarians who managed to be elected amid dubious circumstances.

For example, Alexander Lukashenko, president of Belarus since 1994, is indicative of this trend, although he was never a member of a center-right political coalition. President Vladimir Putin of Russia is another example, having been a member of the centrist to center-right “Our Home—Russia” Party from 1995 to 1999, which supported liberalism and fiscal conservativism. However, from 1999 to 2001, he was a member of Unity, which supported social conservativism, austerity, and Russian nationalism. His “United Russia” Party was similarly simply Russian nationalist, from 2008 to 2012, although this political front was replaced by the far-right nationalist and pseudo-populist “All Russia People’s Front” from 2011 onward. Within Eastern Europe, the dissolution of the Warsaw Pact and the Soviet Union accelerated these changes, especially with the introduction of “shock therapy” economics, which was predicated on the sudden release of price and commodity controls and large-scale privatization. As international corporations competed for investment opportunities to scoop up now available public-sector commodities, ranging from communications, to transportation, to even education, deregulation became a mantra. A wave of deregulation accompanied these changes as nations competed to attract businesses that were suddenly free to locate themselves anywhere resources, labor, and environmental costs were lowest. Thus, the climate of kleptocracy made it easier for authoritarians such as Victor Orban of Hungary to seize power.

Questions for Discussion

- Why might a leader such as Vladimir Putin wish to hide his wealth?

From a historical perspective, one of the most significant forces in the process of economic globalization has been the removal of trade barriers. Trade barriers can come in several forms. For example, quotas, import/export licenses, and tariffs are all common trade barriers. Outright embargoes, including from sanctions, and blockades are forms of trade barriers as well. Thus, when the United States imposed a naval blockade on Cuba in 1962, as mentioned in the previous chapter, this was a very severe form of trade barrier. Import and export tariffs are also technically a trade barrier. Yet, they are much less severe. In most cases, tariffs simply represent a means for federal governments to capture some of the wealth produced by products within their borders and exported—or those imported into their country—and then put that wealth toward government spending, such as social programs (health, education, poverty alleviation), infrastructure (such as transportation networks), or national defense.

From a historical perspective, one of the most significant forces in the process of economic globalization has been the removal of trade barriers. Trade barriers can come in several forms. For example, quotas, import/export licenses, and tariffs are all common trade barriers. Outright embargoes, including from sanctions, and blockades are forms of trade barriers as well. Thus, when the United States imposed a naval blockade on Cuba in 1962, as mentioned in the previous chapter, this was a very severe form of trade barrier. Import and export tariffs are also technically a trade barrier. Yet, they are much less severe. In most cases, tariffs simply represent a means for federal governments to capture some of the wealth produced by products within their borders and exported—or those imported into their country—and then put that wealth toward government spending, such as social programs (health, education, poverty alleviation), infrastructure (such as transportation networks), or national defense.

Also in the last chapter, we discussed policies such as import substitution industrialization, which introduced blocks on imports from industrialized countries to support the production of local industry in developing countries. Developmentalist economics, such as those of Raul Prebisch, advocated for slightly different policies, which promoted collaboration and free exchange among developing countries while imposing tariffs on industrialized countries. Within this context, it is easy to see why developed economies that previously relied on overseas territories acquired by imperialism, such as the United States, France, Germany, and the United Kingdom, would become staunch advocates “free trade,” as “free trade” for them meant the ability to for companies based in their countries to reap enormous profits while capitalizing on the raw materials and cheap labor of the Third World. Hence, the term “Third World” began to shift in its usage in the 1990s, especially in the United States, but also more broadly. Increasingly, the term became associated with the economic conditions of developing economies, meaning desperate poverty and exploitative labor practices driven by First World consumption, especially after the formulation of the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 1995.

The foundation of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) in 1947 was the direct predecessor to the WTO. Initially, the GATT aimed primarily to reduce tariffs and quotas on trade among states outside the sphere of influence of the Soviet Union. The organization met in nine “rounds” of negotiations across nearly five decades. In the first round, tariffs were reduced among core members, most notably the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada, and Australia. By the 1960s, trade taxes in the form of tariffs were reduced to an average of about 15%, which in turn were further reduced to 5% in 1986, during the Uruguay round. As technology was rapidly advancing, intellectual property rights were also discussed, as was dispute settlement. With 123 nation-states participating in the organization by 1986, a substantial portion of which were non-aligned, the structure of the organization had changed. The Uruguay round was the first round where Third World leadership had significantly impacted the outcomes, especially in agricultural trade. Seeking to retain power within the international trade order, GATT leaders proposed to formulate the World Trade Organization (WTO) under the auspices of the continued promotion of free trade. The WTO then grew enormously throughout the following decades. Currently, the only non-participants that are not micro-states are Eritrea, North Korea, Kosovo, and Palestine (recognized by 138 U.N. member states—the vast majority of the world, except for Western Europe, Canada, the United States, and Mexico). The rest of the world, including Iran and Algeria, which are the largest current non-member economies, have some form of membership in the works.

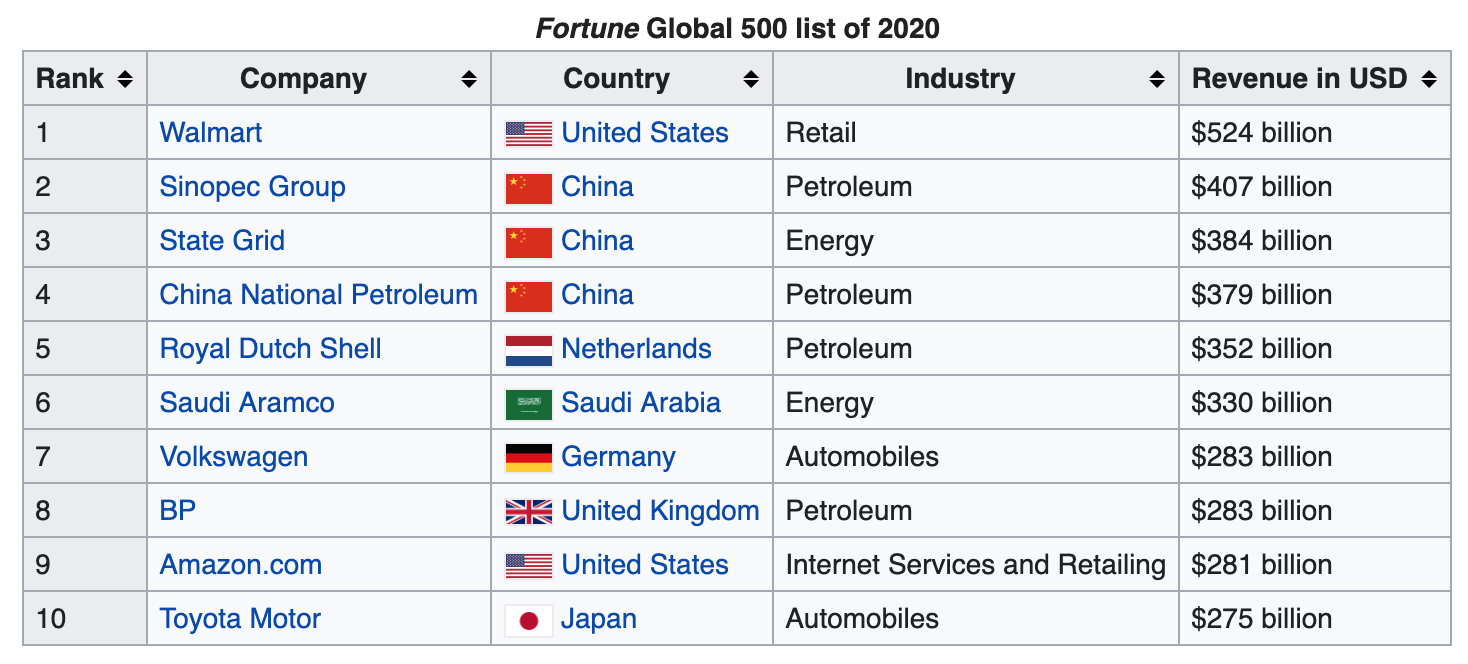

Even as the WTO is headquartered in Geneva, Switzerland, with 164 member states and 25 observer governments, including Liberia and Afghanistan, the historical legacy of GATT as a predecessor organization created an economic core that has been favored by WTO policies. Thus, when the People’s Republic of China proposed to join the WTO, there were 15 years of negotiations as these core members attempted to retain their positions of relative power before the PRC was finally allowed to join in 2001. The WTO’s charter calls on the organization to “ensure that trade flows as smoothly, predictably, and freely as possible”; the historical evidence of decisions from the binding arbitration process exhibits a pattern of favoritism toward wealthier and more-developed economies, especially the initial core economies of the United States, United Kingdom, Canada, and Australia. In essence, these decisions operate like an international trade court, as their decisions take precedence over local and national decisions. Additionally, almost paradoxically, they can be enforced by core countries binding together and threatening to restrict trade if the judgments are not followed. Furthermore, large multinational corporations, such as Walmart (USA), State Grid (PR China), and Amazon (USA), have had a disproportionate impact on the WTO. Such companies have deployed teams of lawyers to advocate for their interests in WTO arbitration.

Up until the year 2000, most of the largest multinational corporations working with the WTO were American, German, and Japanese, meaning that even in the case of German and Japanese corporations, they were essentially “trade allies” of the United States. British Petroleum (2002–4, 2006–9) and Royal Dutch/Shell (2002, 2004, 2006–9) made it into the top 10, although again, both were closely aligned with the American oil industry and so closely aligned that the American backing of the coup in Iran during the Cold War was not the only time the American government intervened on behalf of these corporations, although it was perhaps the most dramatic. The structure of the WTO began to change in about 2009–2010, however, as the first contemporary state-owned enterprise based in the People’s Republic of China (PRC) broke into the top 10 largest corporations in the world by revenue 2009. These state-owned enterprises are not, however, 100% state owned. Instead, they have at least 50% shares held by the government of the PRC, with the remaining shares privately held. Nonetheless, the increase in the prominence of multinational corporations based in the PRC helps to explain the increasing complaints about “unfair trade practices” from the American government regarding the PRC to WTO officials. The distinction was only that large American multinationals were losing ground, while large multinationals based in the PRC were gaining ground, particularly amid the failed policies of the Trump administration.

The more significant global picture of the history of corporations from the 1990s through the 2010s is that enormous transnational corporations have been uniquely suited to capitalize on the increasingly interconnected world. The WTO binding arbitration process takes over a year (15 months, including possible appeals). Over 500 disputes have been heard by the organization, and over 350 rulings have been issued. Yet, most rulings have weighed on the side of large corporations, most often, therefore, at the expense of workers and the environment. Although the rulings have often argued they are in favor of consumers, the evidence does not seem to suggest this is the case. Instead, a decision-making process that favors corporations allows the corporations to set prices, rather than drive them down, while also incentivizing driving down quality, especially by producing products that are cheaper and more hazardous. With about 500,000 such corporations in the world, the impact is significant, especially as the top 10 corporations are often larger than most of the world’s governments if we compare their revenue to the revenue of states. For example, in the 2020 assessment of the largest corporations in the world, the number 10 slot, Toyota (Japan), compares to countries around the top 40 as measured by GDP, such as Colombia, Finland, and Vietnam. If we were to compare the number 1 slot, Walmart (USA), only 23 countries had a larger GDP in 2020 according to World Bank estimates.

Although there was a bit of a shakeup in 2021, resulting from policies attempting to drive economic recovery from the pandemic, Walmart would still rank at the top of the Global Fortune 500 and would be the 26th world’s largest economy, if we were to compare the corporation to a GDP, such as those of Belgium and Thailand. With the number two slots shared by Amazon and State Grid (PRC, electricity), these would still rank as the 36th and 37th world’s largest economies if we compared them to GDP. Finally, even as many corporations, such as Volkswagen (2021, number 10), experienced enormous losses in projected revenue in 2021, the company’s revenue still outpaced significant economies such as Portugal, New Zealand, and Peru. Let’s also keep in mind that Walmart only has 2 million or so employees. Yet, with the history of the inequities in mind, the idea that the governments of countries with 2 million or so people—such as Slovenia, Guinea-Bissau, and Botswana—would exert as much influence in the WTO is almost inconceivable at present. The heads of state of significant economies of much larger countries, such as Israel, Vietnam, and the Philippines, still do not seem to exert as much influence on global trade patterns as Walmart’s CEO and board.

Questions for Discussion

- What are the implications of the top global corporations being larger than all but the largest nations?

- How might a greater shift toward China in the “Top 500” list affect the world balance of political power?

Throughout much of the 20th century, liberal (center-left to center-right) and conservative (center-right to right-wing) parties alike tended to support “free trade” under the auspices that supporting free trade was to support the value of a capitalist-based economy. In the context of the Cold War, especially in the United States, this economic system was juxtaposed against those systems that supported communism or socialism. However, no world economies have ever been entirely “laissez-faire” capitalist economies, just as they have never been entirely communist. Instead, most economies in the 20th and 21st centuries—especially those of the Non-Aligned Movement—have been mixed economies. Mixed economies trend toward the formation of governmental structures that represent forms of either social democracy or democratic socialism. The distinction here is that those economies based on democratic socialism tended to trend toward taking privately held enterprises—especially oil, large parcels of land, minerals, transportation, education, healthcare, and housing, but usually never all of these—and incorporating them as public investments so their governments could more easily mount the profits toward social welfare. In a social democratic system, there is still quite a lot of private enterprise, and large corporations may still make up the bulk of the economy; however, there are government interventions (usually in the form of taxes or regulations) that are intended to promote the welfare of the general public. Both social democracies and democratic socialist economic systems can still be dominated by social conservatives or social liberals.

In the middle of the 1960s, for example, although politicians in the United States’ government frequently issued proclamations of support for capitalists (large business owners whose primary source of income is to make money on investment alone, with no labor input), in practicality, the United States was a form of social democracy, whose politics were dominated by centrist liberal Democrats and center-right conservative Republicans. Both parties claimed to support “free trade,” although doing so, as a matter of practicality, meant asserting American dominance over global trade patterns, meaning “free trade for me, but not for thee,” as it were. By the 1980s, the Reagan administration—misinterpreting principles argued by financial advisor Milton Friedman—made a radical turn toward extreme support of deregulation. Since Reagan’s administration pushed austerity-driven economics first tested in Chile, these neoliberal economic principles came to dominate the political positions of both major parties in the United States from the 1980s onward. While taxes and regulations were lifted, debt as a proportion of the GDP steadily increased, as did wealth inequality. Furthermore, by comparison to similar economies, the measure of life expectancy to healthcare spending in the United States flatlined. Nonetheless, rather than shift domestic policy to address these issues, American administrations adopted a principle that if there was enough trade flowing into and out of the country, this wealth would, in Reagan’s words, “trickle down.” Reagan, hence, often campaigned on establishing a “North American Free Trade Zone,” which would include the United States, Canada, and Mexico.

Following Reagan’s presidency, his vice president and a former director of the CIA, George H. W. Bush, was elected to the presidency. It was G. H. W. Bush who signed the NAFTA agreement in 1988. There were some members of the Democratic Party who were critical of the initial NAFTA agreement, based on the principles of their allegiance to large unions. However, these criticisms did not articulate their concerns for Mexican or Canadian workers. Such international solidarity would have been read as socialist or communist, and any hint of international worker solidarity had resulted in purges from the leadership of American unions during and after the Second Red Scare from the 1950s through the 1980s. Instead, they articulated their concerns as worrying about “American workers” who would “see their jobs shipped overseas.” In 1993, the United States’ only significant center-left democratic socialist politician was an Independent congressman from the small northeastern state of Vermont: Bernie Sanders.

Congressman Sander’s criticism of NAFTA, published in the Vermont Times in October 1993, was rooted in his recent trip to Mexico. He argued, contrary to Republican positions that NAFTA would help everyone and American union organizers who argued that NAFTA would hurt American workers, that NAFTA would hurt both American workers and Mexican workers. He also levied substantial criticism at the Mexican government’s PRI party for, since historically proven, authoritarian practices and closed with the statement, “American corporations must reinvest in America, and not exploit desperate third world workers.” Little known and with little impact, Sanders was virtually the only voice in the American government to criticize NAFTA out of concern for all the workers of the world. This is a position he retained in later criticism of CAFTA, G. W. Bush–era bilateral trade agreements, and the Obama-era Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), although in criticism of later agreements, he also often levied environmental concerns. However, Bernie Sanders has often been misquoted and his ideas misrepresented, as American right-wing conservatives and centrist liberals alike were not interested in the views of the little-known congressman at first. When they became interested, it was only because of his significant increase in political visibility after he stepped late into the 2016 Democratic Primary to challenge the presumed victor—and to that date, unchallenged candidate—former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton.

Secretary and former Senator Hillary Clinton was also the former First Lady during the Clinton administration, the same administration that had signed a ratified NAFTA agreement after it had passed a Republican-dominated congress. Thus, debates over NAFTA and free trade were frequently centered in the 2016 Democratic Primary and 2016 Presidential Election, although in the case of the Republican candidate, the interests of the many-times-bankrupted real estate tycoon Donald Trump were not to criticize NAFTA out of the interest of workers. Instead, members of his campaign argued from a right-wing to a far-right position of big business elites that NAFTA was a boon to American businesses and thus the American economy. Although the short-term negotiation process was viewed internationally as broadly damaging to foreign relations, tumultuous, and sometimes an unnecessary headache to simply re-brand Obama-era and prior agreements with a Trump administration stamp of approval, long term, the formulation of trade agreements from Republican administrations has barely changed.

The Reagan and G. H. W. Bush administrations supported NAFTA, with NAFTA being ratified by a Republican congress and a Democratic (Bill Clinton) president. The G. W. Bush administration formed more than 10 bilateral trade agreements based on the same principles as NAFTA and formulated the similar Dominican Republic–Central American Free Trade Agreement, commonly known as CAFTA, in 2004. Furthermore, the Obama administration began the process of negotiating the Trans-Pacific Partnership, which, despite bluster from the Trump administration, resulted in the formulation of the rebranded Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership—although, ironically, the U.S.’s potential position in that or any future similar deal has been substantially weakened.

Free trade agreements, along with their counterpart political and economic unions, such as the European Union, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), and the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC), attempt to create trade zones with certain types of lower trade barriers between signatory and member nations. For example, by eliminating agricultural tariffs, Mexico became the second-largest market for U.S. agricultural products, especially meat and corn. However, since the U.S. government kept in place the trade barrier of enormous corn subsidies, this prevented Mexican farmers from importing corn into the U.S., and U.S. producers undercut their production in Mexico. Mexican farmers lost their farms and biodiversity declined, especially as wind-pollinated American corn varieties have begun to endanger local varieties. Resulting monocultures are, furthermore, vulnerable to disease and pests, and in the worst circumstances, a single blight damaging a monocrop could result in a transnational famine, let alone economic ruin. Indeed, 11 months after NAFTA was ratified in 1994, while the Canadian and American economies continued to grow, the Mexican economy collapsed. Mexican investors had poured their capital into the U.S., and the tax income of the Mexican government crashed. When they approached the International Monetary Fund (IMF) for funds, the IMF imposed austerity programs and a deflation of the Mexican currency as a condition of the bailout. In the U.S., the press, pundits, and experts tended to ignore or misrepresent the 1994 Mexican peso crisis (nicknamed the “tequila crisis”).

Another significant impact of NAFTA for Mexico has been the rise of largely duty-free or tariff-free factories, especially in close proximity to the U.S.-Mexico border. Known as maquiladoras, there are also similar factories that opened in Paraguay, Nicaragua, and El Salvador under similar trade negotiations. Although maquiladoras date to 1964, when the Mexican government introduced its “frontier industrialization program” to build industrial zones in the U.S.-Mexico borderlands, maquiladoras dramatically grew after 1994. By 1999, their employment numbers had doubled, and by 2004, they accounted for 54% of Mexico’s exports to the U.S., while exports to the U.S. had grown to a 90% share of all exports for the Mexican economy. U.S. companies tapped into this labor market because the wages were much lower, averaging just $0.55/hr in 2015. Similarly, wages in factories in Indonesia, Vietnam, Cambodia, and Bangladesh were very low, as were those in the CAFTA countries. Americans came to know these centers of production as “sweat shops” and would especially associate them with the garment industry, although maquiladoras and factories more broadly in such “free trade zones” produced everything from computer parts to refined agricultural products. They also had fewer environmental regulations, and workers suffered enormously because of the lack of worker-safety protections. Some countries like Mexico would increase worker protections but would exempt maquiladoras from those protections.

Despite the low pay relative to American and European standards, Third World workers, including those in Mexico, shifted to manufacturing jobs in the 1990s through the 2000s. These positions were much higher paying than agricultural worker positions. For example, even in the 2010s, factory workers in Vietnam were making several times the compensation of their counterparts in agricultural sectors. However, worldwide gains in manufacturing jobs in the Global South have been matched by relative decreases among manufacturing-sector in jobs in the Global North. Furthermore, the growing industries in the Global North were predominantly in the service sector, in high-tech jobs (such as computer engineering), and in the financial sector. They were not positions that factory workers could easily move into if their employers closed shop and opened competing factories in, say, Bangladesh. Despite even lower wages in the Asia Pacific and Central American countries, along with the Great Recession of the late 2000s, there remain some 3,000 or more maquiladoras in Mexico close to the U.S. border today.

Questions for Discussion

- Why did NAFTA receive so much bipartisan support in the U.S. before its passage?

- Were the overall effects of NAFTA positive or negative for the U.S.?

- Who benefitted the most? Who suffered the most?

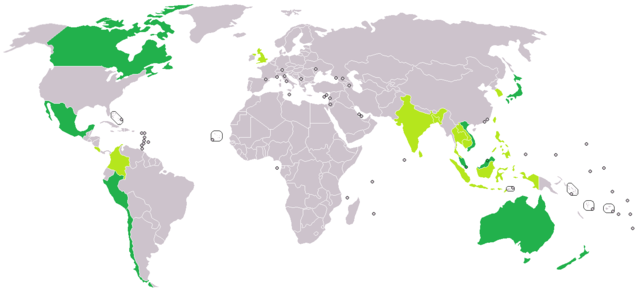

Initially, like the NAFTA trade bloc, the Trans-Pacific Partnership was designed to create a trans-national trade association. However, unlike NAFTA, the TPP was not initiated by the United States. Instead, it was initiated by the oil-rich Sultanate of Brunei (on the island of Borneo), Chile, New Zealand, and Singapore in 2005. Beginning in 2008, multilateral negotiations resulted in countries in the Americas (the United States, Mexico, Peru, and Canada), along with countries in Asia (Japan, Malaysia, and Vietnam) and Australia, joining the agreement. Under the Obama administration, American advisors specifically sought to join the agreement as a means of staving off the influence of the People’s Republic of China, especially in Southeast Asia. The aim was not just to remove trade barriers among partners but also to introduce standards of environmental protection, human rights, intellectual property, and labor protections among signatories. However, some critics argued that these protections were not enough and that corporations would have too much power in the arbitration process the TPP was going to establish. Other critics, typically within the right to far-right wing of American, Japanese, Australian, or Canadian politics, argued that American companies would be the target of arbitration processes and lose millions.

Based on the premise that the TPP was a “bad deal” for American corporations, the Trump administration withdrew from the agreement in 2018. However, the key member states of the agreement reformulated and expanded, less the 22 provisions that the United States pushed for. Additionally, South Korea, Ecuador, Taiwan, and the United Kingdom—which has been in the process of withdrawing from the European Union—have all submitted applications to join the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for the Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), which is essentially the TPP, but larger, and minus the influence of the United States. As of this writing, the Biden administration does not plan to join the CPTPP but instead hopes to formulate a larger multinational organization, under American leadership, which would supplant it.

Questions for Discussion

- In what ways might TPP be more challenging for the U.S. than NAFTA?

- How would you characterize the positions of the United States on trade agreements within the context of the international community?

An important historical context is recent centrist-liberal Democratic and right-wing conservative Republican attempts have been made to re-assert the United States as a major global trading power has been a perceived—and real—increase in East, South, and Southeast manufacturing. Japan had industrialized in the late 19th century, like the United States and Brazil. Yet, $2 billion USD in direct investment after WWII jump-started the recovery of the country’s economy, as did letting the Japanese government off the hook for war reparations, which might have been used for growing the economies of the Koreas, the then Republic of China, Vietnam, Myanmar, the Philippines, or Indonesia—had they been paid to those countries that suffered under Japanese imperialism. Initially, low-wage industries produced in Japan for American consumer markets. As most profits were redirected toward the growth of manufacturing centers and technological innovation, the production economy quickly shifted. Japanese manufacturers began producing cameras, film, TVs, audio equipment, and cars. By the 1980s and 1990s, Japanese companies were strong competitors in markets across North America and Europe, along with East and Southeast Asia. Singapore, South Korea, and Taiwan all adopted Japanese models of development from the 1960s through the 1970s, while being bolstered by Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) from the United States that was intended to work as soft diplomacy in the context of the Cold War. For example, USAID and Japanese development firms both worked to build bridges and roads in Cambodia between the 1950s and the 1960s. Although American military and development forces pulled back from Southeast Asia in the 1970s, negotiations between the Nixon administration and Mao Zedong of the People’s Republic of China introduced new dynamics into the region in the middle of the decade.

The death of Mao Zedong in 1976 is typically portrayed as a monumental shift in the history of the People’s Republic of China. Although the changes brought by the leadership of Deng Xiaoping were indeed substantial, they were also continuations of already existing trends within the Communist Party. Deng Xiaoping had been a veteran of the Long March, the Second Sino-Japanese War, and the Chinese Civil War. He had worked in Tibet to consolidate PRC control there before returning to Beijing. He was instrumental in putting in place economic policies during the Great Leap Forward, and he was active in the anti-rightest campaign that purged a number of critical intellectuals, although he would later come to criticize not only aspects of even his own policies but also the Great Leap Forward broadly. Thus, he had been purged, not just once, but twice during the Cultural Revolution for his criticisms of the Communist Party’s conservatives. Nonetheless, because of his dedication to the party, the revolution, and his years of loyalty, he was restored on both occasions, and the adept politician outmaneuvered Mao Zedong’s immediate successor, Hua Guofeng, to become the de facto leader of China from 1978, although he was technically the vice chairman of the Communist Party under Hua Guofeng.

In the 1980s, the leadership of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) desired to prevent the rise of a single leader who would reign for decades, like Mao Zedong had. Thus, in a move to democratize party leadership, they abolished the office of chairman in 1982 and divided the duties of the office, although most of the duties were passed to the post of general secretary. Hu Yaobang then stepped down as chairman of the Communist Party and was appointed to the revived post of general secretary. However, there was a Central Advisory Commission that, in effect, dictated the actions of the rest of the government offices. As chairman of the Central Advisory Commission, Deng Xiaoping was, in essence, the paramount leader of the country from 1982 through 1987. In 1987, Chen Yun took over the post and was instrumental in the so-called opening of the economy of the PRC during the late 1980s and early 1990s. However, after the 1989 Tiananmen Protests, Jiang Zemin steadily increased in power and would become the general secretary of the Communist Party, eclipsing the power of Chen Yun, and remaining in that position from 1989 through 2002. It was Jiang Zemin who introduced the term “socialist market economy,” which has become the guiding understanding of the economy of the People’s Republic of China from the early 1990s through the present.

The term “socialist market economy” and the “opening of China” have often been conflated with the re-introduction of capitalism into the country. However, this interpretation is imprecise at best—and outright misleading at worst. A socialist market economy is not a capitalist economy. Instead, it is a form of socialist economy wherein there is state enterprise and public ownership of many industries. However, the measurement of the success of production is not guided by the forces of absolute production—or even consistent production—in a socialist market economy. Instead, market measures, such as whether a production center meets demand with its supply, are the measures of success. There is some private enterprise in a socialist market economy model, although historically, there had always been some form of private enterprise in the PRC. Thus, in this sense, the socialist market economy was simply accepting that some private enterprises existed and state enterprises might move in accordance with market forces of supply and demand. Nonetheless, the understanding of a socialist market economy is still that it is an early phase of socialism and that there is a goal to move toward greater elements of the economy being held in the public trust or controlled by state-run enterprises. Furthermore, there was a push toward very significant and, arguably, successful means of wealth redistribution.

Coupled with the socialist market economy, the People’s Republic of China in the 1980s had a competitive advantage that continued through the 21st century. Simply put: there was a ready supply of cheap labor. Furthermore, leaders, including Deng Xiaoping, made a semi-frequent practice of devaluating the Chinese yuan. Consequentially, when the currency was devalued, the cost of exports lowered and the number of purchasers seeking to buy those exported goods at a discounted rate increased. Additionally, as government surpluses of funds increased, savings could be invested in the government bonds of other countries. This allowed the government of the PRC to purchase significant portions of the “debt” owed by various nations. Although there has been quite a lot of clambering about the portion of the U.S. debt the PRC holds, the number is quite small. Instead, a significant majority of the American debt is publicly held by Americans (22.3 trillion USD in 2021). Of the foreign governments that own U.S. debt, Japan is the largest (1.3 trillion USD), while the PRC ranks second (approximately 1.05 trillion USD in 2021). In other words, no foreign country owns more than a 5% share of the U.S. debt. That said, the PRC does own significant shares of the debt of other governments. For example, there are at least a dozen countries that owe 20% of their GDP to the PRC, including Djibouti, the Republic of the Congo, Cambodia, Laos, Niger, Zambia, Mongolia, and Kyrgyzstan. These markets guarantee that a rising middle class in the PRC has been supported through import and export exchange, along with primary and secondary manufacturing sites. For example, clothing that used to come from the PRC is now manufactured by Chinese companies in Cambodia.

The enormous economic success of the PRC’s adoption of a socialist market economy is typically illustrated by pointing toward a few basic points. From 2000 to 2010, the poverty rate dropped from 49.8% to 17.2%. In nearly the same decade, the middle class increased from 7% to 54%. While only 2% were upper-middle class in 2012, 54% are expected to be upper-middle class by the end of 2022. The poverty rate dropped again from 17.2% in 2010 to .6% by 2019. In other words, more than a billion people improved their standards of living in one of the most significant shifts in living conditions in the history of the world. Nearly 850 million were lifted out of extreme poverty. The dramatic shift is even more impressive when compared to the United States, where the poverty rate has hovered between 10% and 15% for decades and the extreme poverty rate has essentially sat at 5% since the 1980s, although, admittedly, pandemic relief temporarily massively cut child poverty in the United States in 2021. Nonetheless, the picture that poverty alleviation coupled with economic success has created for the contemporary global community is one of a “rising Chinese power,” a perception that contemporary leaders, including Jiang Zemin and Xi Jinping, have leaned into. Indeed, demand from the economy of the PRC has a significant impact on the markets of Southeast Asia, South Asia, Southwest Asia, Central Asia, and Africa. Massive tech giants like Huawei, JD.com, China Mobile, Alibaba, and Tencent have had a significant impact on tech markets. Furthermore, companies that are not based in the PRC, such as Apple, Lenovo (from Hong Kong), and IBM all came to be assembled in the PRC, with much of the raw materials for these goods being manufactured in Africa or Southeast Asia through Chinese-partnered companies.

A feature of the dramatic increase in the production of the contemporary economy of the PRC has been a matched increase in pollution. In the 21st century, the PRC became the world’s number one polluting country and the greatest emitter of carbon dioxide. However, when we weigh these measures by population, especially CO2 emissions, the PRC falls down the list of concerns. Nevertheless, it is fair to say that the challenge of producing a massive amount of consumer goods without destroying the environment is a challenge that faces both the PRC and the United States, along with the European Union, Brazil, and other major global economic producers, such as oil-rich Venezuela and the Gulf States. In the last chapter of this book, we will consider these issues in more detail; however, it is pertinent to note that the government of the PRC has taken a much stronger stance on pollution in recent years, and the general social climate of the PRC has become less tolerant of environmental destruction in the name of development, which is commonly viewed as a welcome change. The contemporary “Belt and Road Initiative” (BRI) seeks to connect the PRC to the rest of Asia, Europe, and Africa by drawing upon the trade networks of a “New Silk Road” across Asia and a “New Maritime Silk Road” across the Indian Ocean. In particular, the natural environments of Southeast Asia, East Africa, and South Asia will be important areas of future study in this context. The approach of the PRC here would thus contrast with, say, American approaches to Latin America throughout most of the 20th century—which is to say, those American approaches viewed Latin America as very much “out of sight, out of mind.”

Questions for Discussion

- In what ways was the U.S. instrumental in creating the “Asian Tiger” economies? Asian Tigers is a term given to the economies of four countries – Singapore, Hong Kong, South Korea, and Taiwan.

- How did Mao Zedung’s death change Chinese economic and trade policy?

The European Union grew out of a 1957 trade agreement that expanded on GATT to form the European Economic Community (EEC), including France, Belgium, West Germany, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg. Like NAFTA, the EEC reduced tariffs and other barriers to trade. In 1993, the European Union was formed, including the original EEC members as well as Austria, Denmark, Finland, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, and the United Kingdom. In 1999, 16 member nations adopted a single currency, the euro, although Sweden and the U.K. retained the krone and the pound sterling. The English financial district called the City of London has always been a center of European banking and finance, and the British were desperate to protect the pound against the German deutschmark and the growing power of the Frankfurt-based European Central Bank. In the early 2000s, several Eastern European nations joined, bringing membership up to 28 nations. Most of these new members adopted the euro as well, and after the global financial crisis of 2007–8, the Eurozone established emergency loan procedures that allowed richer members to bail out the economies of poorer members in exchange for what the lenders termed economic reforms. Borrowers often viewed these reforms as a takeover of their economies and harsh austerity programs.

In June 2016, the United Kingdom held a referendum, and in a shocking nationalist vote, the majority decided to leave the European Union. Brexit is scheduled to go into effect at the end of March 2019. The residents of Scotland and Northern Ireland both voted to remain in the E.U., but their votes were outweighed by the English, and they will be forced to leave along with the rest of the U.K. The Republic of Ireland will remain an E.U. member, which will complicate the situation on the border between Ireland and British Northern Ireland. The economic impact on Britain is difficult to calculate, but E.U. nations seem disinclined to allow Britain to retain the favored trade status it currently enjoys. And although many British people and politicians wished to reverse the decision to leave, the E.U. was unwilling to pretend the Brexit decision never happened. During 2020, an eleven-month transition period was agreed upon to allow negotiators to establish post-Brexit policies. At the end of 2020, an agreement seems to have been reached that will allow the U.K. and the E.U. to continue trading without tariffs in 2021.

Questions for Discussion

- What were the arguments for and against “Brexit”? Which do you find more compelling?

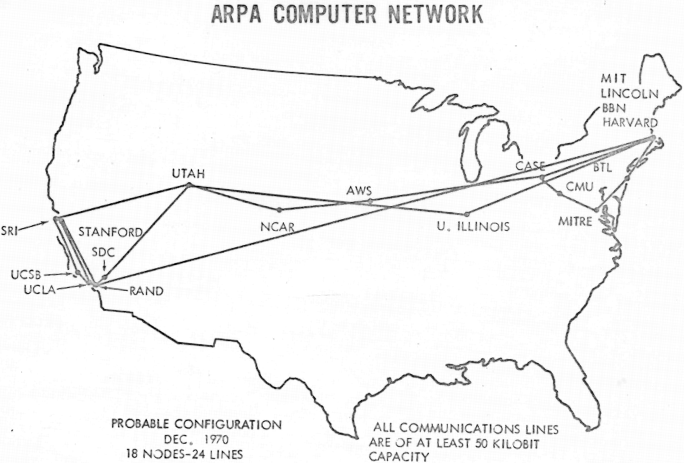

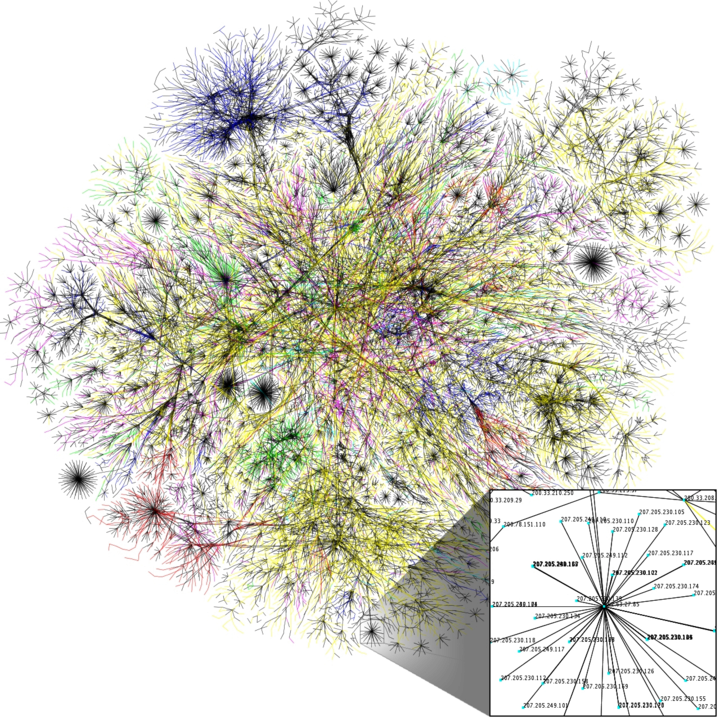

In addition to the increase in international trade, global culture has been permanently changed by communications technology. Computer networks and cell phones continued a process begun with the printing press, the telegraph, radio, and television. Each of these technologies has been used to spread ideas to wider audiences, often against the wishes of those in power. More recent inventions like fax machines, data communication via modems, the internet, and most recently, smart phones and social networks have been used to spread news of events like the Tiananmen Square protests, the Arab Spring, and the Egyptian Revolution of 2011. In spite of the efforts of some nations like China and Saudi Arabia to censor media and limit internet access, it is increasingly difficult to firewall societies from the global media culture.

Because the virtual world is becoming as important to the global economy as the physical world of “bricks and mortar” commerce and communication, let’s take a moment to review the technological, government, and business changes that enabled it. One of the first computer networks was the semi-automatic business research environment (SABRE) launched by IBM in 1960, which initially connected two mainframe systems and grew into an airline reservation system. In 1963, American psychologist and computer scientist J. C. R. Licklider proposed a concept he called the “Intergalactic Computer Network” when he became the first director of the Pentagon’s Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA). Licklider described it as “an electronic commons open to all, the main and essential medium of informational interaction for governments, institutions, corporations, and individuals.”

ARPANET, begun in 1969, was a network of networks, joining government facilities and research universities on a system dedicated to official communications. It was permissible for researchers and users to occasionally communicate personally with each other using email. Commercial and political communications, however, were strictly forbidden. A computer scientist named Ted Nelson developed the basic ideas that became hypertext and the web between 1965 and 1972. Nelson’s version of hypertext was based on the idea that there would be a “master” record of any document on the network. Exact copies of that document (which Nelson called transclusions in his 1980 book, Literary Machines) would point back to the original. Ideally, rather than just referring to the original, they would actually call up the original document wherever possible, eliminating the proliferation of copies.

This ideal was never really achieved, because even though storage was expensive, bandwidth was even scarcer. This is unfortunate, because the existence of bi-directional links would have allowed the owner of a document to know where and when it was used and to have received compensation for its use. Two-way linkage was much more difficult to implement than a one-way hyperlink that launched the user to a new place on the web. Apple co-founder Steve Wozniak compared the two in a speech about Nelson in the 1990s, saying one-way linking was a cool hack, while two-way linking required computer science.

Questions for Discussion

- How do computers and communication networks affect world culture and politics?

- What do you think the internet would be like now if it had not originally been a scientific/government network?

After the introduction of Apple Macintosh and IBM Personal Computers in the 1980s and the growth of online communication and file-sharing using services such as Compuserve and Prodigy in the early 1990s, in 1992, an online game provider called Quantum Link that had renamed itself America Online offered a Windows version of its free-access software. AOL free trial CDs became ubiquitous; CEO Steve Case claimed that at one point in the 1990s, half the CDs produced worldwide had an AOL logo. By the mid-1990s, AOL had passed both Prodigy and CompuServe, and in 1997, more than half of all U.S. homes with internet access got it through AOL. The economic power of the online access was becoming apparent: in 1998, AOL acquired Netscape; in 1999, it acquired MapQuest; and in 2000, AOL merged with Time Warner.

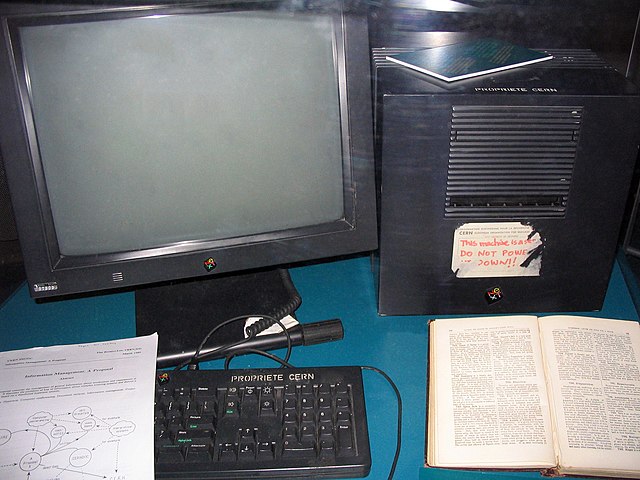

The commercial nature of subscriptions like AOL stood in sharp contrast, for a while, to the early internet. The inventor of the World Wide Web, Tim Berners-Lee, was a scientist at CERN in Switzerland when he wrote “Information Management: A Proposal” in March 1989. Somebody jotted on the front page of the paper, “Vague but exciting,” and Tim was given time to work out the details on a NeXT computer in his lab. By October 1990, Berners-Lee had written the three basic technologies of the web: HTML (Hypertext Markup Language), the formatting language of the web; URI (Uniform Resource Identifier, a.k.a. URL), which contains the protocol (http, ftp, etc.), the domain name (example.com), and folder and file names (like /blogs/index); and HTTP (Hypertext Transfer Protocol), which allows the retrieval of linked resources.

Being a government-funded research facility, CERN decided to make the protocols freely available, but it was the development of the MOSAIC browser by graduate student Marc Andreessen in 1993 that made Berners-Lee’s inventions the solid basis of the web. Andreessen graduated, moved to California, and met Jim Clark, who had recently left Silicon Graphics. They formed Netscape and made their browser, called Navigator, available for free to non-commercial users. Netscape Navigator was destroyed by Microsoft’s decision to bundle its own browser, Internet Explorer, with Windows 95. Microsoft made it very difficult for PC manufacturers or even users to uninstall IE and use Netscape and Java, which led to an antitrust case in February 2001, in which the court ruled that Microsoft had abused its monopoly powers. Netscape never recovered from losing the “first browser war,” however, and was acquired by AOL in 1999.

From 1991 (when there was only one at CERN) to 1994, when Yahoo launched, the number of websites rose to 2,738. The following year, when Altavista, Amazon, and AuctionWeb began, the number of websites had increased nearly tenfold to 23,500. In 1998, when Google launched, the number of websites had jumped tenfold again, to 2,410,000. The early years of the web, known as Web 1.0, were a period when people with modest skills could acquire a domain and build a website. One of the first powerful and intuitive apps for building websites and pages was Microsoft’s Frontpage. It was a Windows app that provided a WYSIWYG design interface and output usable HTML code. Millions of people used the program to build personal and small commercial websites. Discontinued in 2003, Frontpage was not replaced by anything with similar power and ease of use. Partly this is because in Web 2.0, the do-it-yourself (DIY) element of the web has largely disappeared.

In 1999, a new generation of the web called Web 2.0 was announced, which claimed to focus on participation by users rather than people simply viewing content passively. One example of this participatory nature of the new web is the proliferation of social media. Another is people posting videos on YouTube. The web has also become a site of commerce, though, so the most important instance of “participation” by web users is as consumers buying stuff—either web content like Netflix videos or iTunes music or real-world goods on e-commerce sites like Amazon.

By 2001, when Wikipedia began, there were over a half billion internet users and over 29 million websites. There were a billion users in 2005, when YouTube and Reddit began, but growth had slowed to only 64,780,000 websites, and a much larger percentage of them were commercial rather than personal. By 2010, when Pinterest and Instagram launched, there were 2 billion web users, and the number of websites had actually declined from the previous year for the first time, to about 207,000.

In the 2010s, the rest of the world caught up to the U.S. in web use and website building. By 2015, there were well over 3 billion people using the web, and by 2017, there were 1.7 billion websites. Since then, the number of websites has decreased, dropping by nearly 10% per year. And about three-quarters of these new websites aren’t active but are parked domains or redirects. The actual number of sites in active use is probably closer to 200,000.

For people who wanted a presence on the web but didn’t have the skills or interest to own a domain or code a website, what some have called Web 2.5 saw the beginning of social networking sites. The biggest of these from 2003 to 2008 was called Myspace. People could create a profile page, post images and multimedia, and see what their friends were up to. It was much less structured than what we’re used to today, allowing users a lot of flexibility to personalize their pages. Myspace was overtaken by a service, Facebook, that provided even more ease of use and uniformity. Facebook is extremely easy to use, which may be why it has recently become the place for grandparents to stalk millennials.

Questions for Discussion

- Most of the hardware and software you use was developed during your lifetime. Do you think this has implications for a “generation gap” between your generation and your parents’ generation?

The final element in the story of computing and networks involves the battle between free, open-resources and commerce, which we’ve already seen in the growth of the web. Operating systems in early mainframes and personal computers were tightly controlled by manufacturers like IBM, Digital Equipment Company, or Hewlett Packard; software businesses like Microsoft (DOS and Windows); and a number of workstation companies like Sun Microsystems and Silicon Graphics, which each owned a proprietary version of an operating system that had originally been developed by researchers at AT&T Bell Labs (which was prevented by an anti-trust ruling to get into computers) and the University of California, Berkeley. The Uniplexed Information and Computing Service, called UNIX, had originally been more or less open but had become commercialized when AT&T sold its rights to a network software company, Novell, which later sold those rights to Santa Cruz Operation (SCO). In time, other organizations released versions that only ran on their hardware (and often cost thousands of dollars), including IBM (AIX), Microsoft (Xenix), Sun Microsystems (Solaris), and SGI (IRIX)—all proprietary distributions with similar functionality.

![By Unknown photographer who sold rights to the picture to linuxmag.com - Linuxmag.com; The image is from an article in a December 2002 issue of Linux Magazine[1], CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=17991 Colored photograph of Linus Torvalds in grey short sleeved shirt with arms crossed over chest](https://louis.pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/sites/18/2022/05/352px-Linus_Torvalds-220x300.jpeg)

In 1991, Finnish graduate student Linus Torvalds became frustrated with the high cost of UNIX. He wrote an operating system kernel in C, which he planned on calling Freax. Instead, early users called it Linux. The open-source operating system rapidly gained popularity among hackers due to its free distribution and its easy configurability. A programmer could configure the Linux kernel with just the features desired, which led to an explosion of both OS distributions (Red Hat, Debian, Ubuntu, Darwin, Android) as well as uses in embedded systems that were becoming popular. PC manufacturers like IBM and Dell adopted Linux as an option to reduce the cost of their systems and break Microsoft’s monopoly on the OS. Linux became especially popular for running file servers and internet routers, replacing expensive proprietary systems like IRIX, Microsoft NT, and Cisco. And organizations like NASA discovered that clusters of networked, off-the-shelf PCs running Linux could rival the computing power of proprietary supercomputers. Companies like Sun and SGI found the markets for their workstations and servers disappearing overnight. Currently, all the systems on the Top 500 supercomputer list run Linux.

Questions for Discussion

- How did the development of open source operating systems like Linux change the economics of high tech?

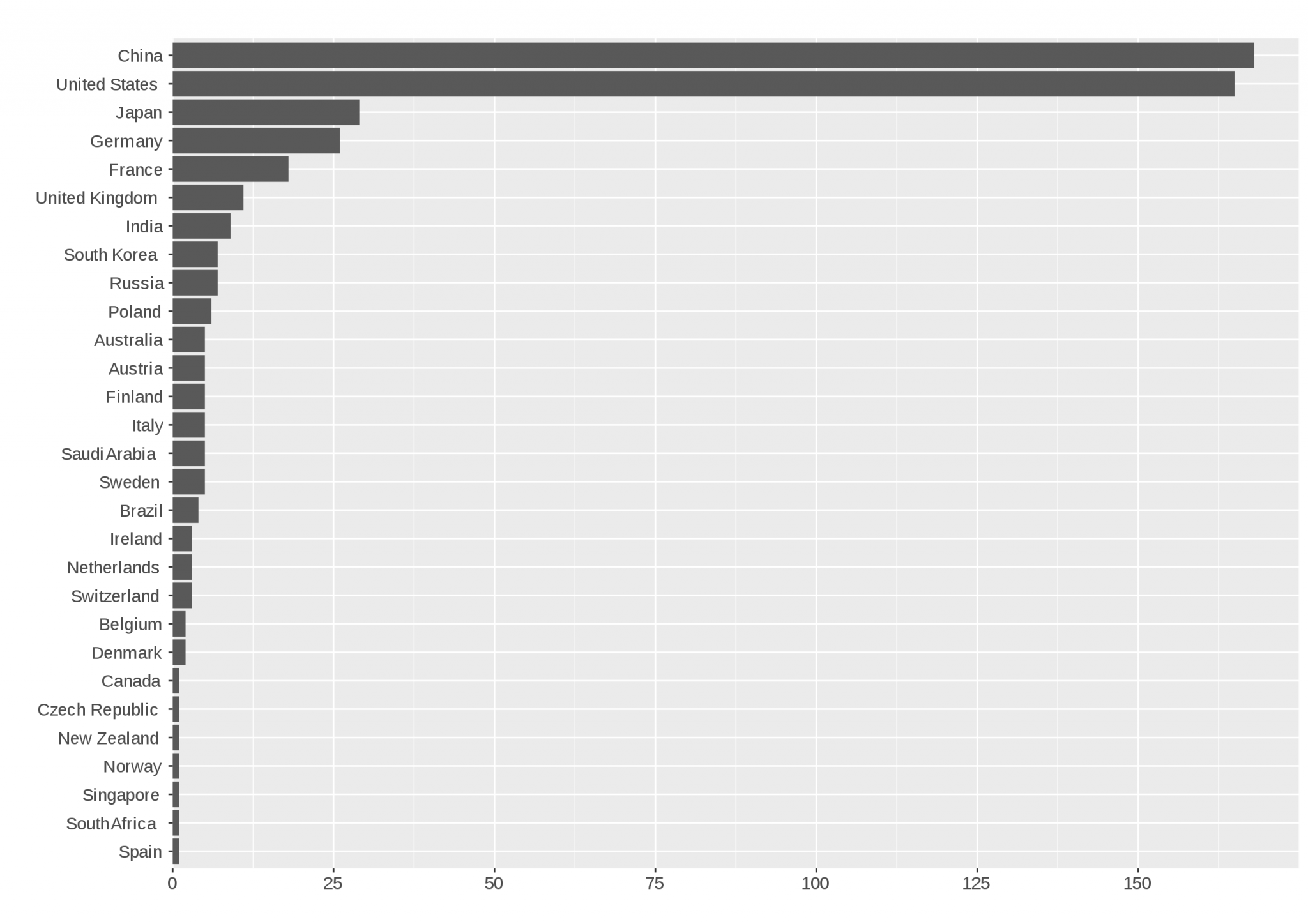

Fifteen years ago, China had no computers on the Top 500 list. Today, it owns the top two spots. The #2 machine, which was the world’s fastest supercomputer from 2013 to 2016, uses Intel Xeon CPUs. But in 2015, the U.S. government banned the sale of these processors to China. The official reason for the ban was national security concerns, but many suspected that a desire to recover the status as the world’s fastest computer for America may have been a strong motivation as well. China responded by very rapidly shifting to using its own Sunway CPUs, based on a new architecture and instruction set completed in 2016. The Sunway processors reportedly have 260 cores, and the “Taihulight” supercomputer built from them runs at up to 125.44 petaflops (1 petaflop = one thousand million floating point operations per second), a lead the U.S. and Japan are unlikely to be able to catch up with anytime soon.

As computing power enables increasingly complex artificial intelligence (AI) systems that can control financial trading systems, power grids, and scientific research, the challenges of national technology competitions become apparent. But even the new web technology has its dark side. Social media has been implicated in helping cause the genocide in Myanmar against the minority Rohingya population. Russian meddling and manipulation of Facebook data by a company called Cambridge Analytica may have influenced the 2016 Brexit vote. Foreign hacking and social media manipulation were both alleged during the 2016 and 2020 U.S. presidential elections, although it’s unclear whether the intervention changed the outcome. While investigating charges of Russian interference, details have come to light of just how compromised social media sites like Facebook have become and how much of their users’ data they hold. And in 2013, American whistleblower Edward Snowden released information to journalists showing that intelligence agencies such as the NSA and British GCHQ are systematically invading the privacy of citizens in several illegal ways. As a result of these disclosures, Snowden has been forced to live in exile in Russia. It is not clear, however, whether the practices have been discontinued.

Questions for Discussion

- Which do you think is a greater threat to the future: foreign domination of high-performance computing or the government’s invasion of citizen privacy? Why?

Finally, even when there’s not an adversary regime like Russia spreading disinformation, social media algorithms create “filter bubbles” in which people only see information that doesn’t threaten their worldviews. To generate greater advertising revenues, social media platforms and search engines routinely direct users to information that will attract and hold their attention for the longest time possible. The objective of the algorithms is not necessarily to promote a certain worldview but simply to keep the user engaged so that more ads can be placed and sold. However, as a result, users are directed to information that conforms with their “profile” of beliefs and biases. When information that does not conform to the user’s preconceptions is presented, it is often presented in an adversarial way, to generate anger (which is another way to insure engagement). News and information are tailored either to conform to audiences’ beliefs and prejudices or to outrage. As time goes on, people on different sides of issues can literally find themselves living in different worlds, basing their beliefs on different data, and believing the other side is irrational and evil.

Explore More

View Eli Pariser’s TED Talk Beware online ‘filter bubbles’: Inspiring: Informative: Ideas

Some have argued that global media access disproportionately benefits nations like the U.S., which has a multi-billion-dollar content-creation industry, and that it spreads values some societies disapprove of, including consumerism and pornography. Even in the U.S. and the developed world, the internet is changing from the democratic, peer-to-peer sharing institution it was designed to be into a platform for commerce and media consumption. In the early days of the internet, communication was text-based because bandwidths were low. The advent of fiber optic network backbones in the 1990s and the World Wide Web created the opportunity to communicate using images and, ultimately, streaming video. 4G and 5G cellular networks allow media to be streamed to smartphones and tablets. This rapidly expanding bandwidth created an opportunity for the internet to replace broadcast television just as it had replaced the analog landline telephone network. But access may not be universally available for long.