9 World War II

In many ways, World War II was a continuation of hyper-nationalist tendencies that were first seen during World War I, especially in Europe. Germans supported Hitler and the Nazis because they promised to overcome the humiliation of Germany at the Paris Peace Conference in 1919: being forced to admit “war guilt,” to pay massive reparations, and to limit the size and quality of their armed forces. The Nazi regime promised to reverse all of it and place a powerful new German Empire as the dominant force on the continent—and perhaps the world.

However, World War II was also a result of the worldwide reaction to the Great Depression, which was seen by many as not only a failure of capitalism but also a failure of democracy. Fascism and communism seemed to some to offer the only plausible reactions to the crisis—remember that although neither the Nazi nor the Communist Parties in the German Weimar Republic ever won a majority in a contested election, by 1932, most German voters opted for one or the other, with a smaller minority voting for democratic socialist alternatives, and the combined majority essentially voting against various forms of capitalism and liberal democracy. Germany was not alone in embracing authoritarianism—the same happened all over Eastern and Central Europe, Latin America, and most importantly, Japan. The last chapter presented how the Japanese military, taking the initiative against the weak objections of Japan’s elected government, initiated the conflict that would become World War II by invading and occupying the northern Chinese province of Manchuria in 1931. Again, it is striking how similar the racial beliefs in the Japanese military were to those of the Nazis: the “Yamato” people of Japan had a special mission to dominate East Asia in the same way that the “Aryans” of Germany were destined to rule all of Europe.

The Road to War in Europe

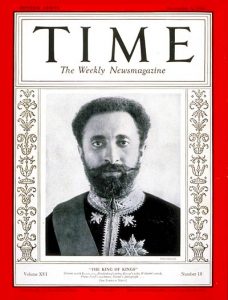

The belief that their nation’s greatness lay in war and conquest was fundamental to fascist ideology in both Italy and Germany. While Hitler was still consolidating the Nazi regime and rebuilding German armed forces in violation of the Versailles Treaty, Mussolini decided to act. In October 1935, Italy invaded independent Ethiopia from its colonies in Eritrea and Somalia. The Italians had been defeated by the Ethiopians in 1896; this time was different. Using air power and poison gas, Mussolini’s military swept through Ethiopia. By the end of 1936, most pockets of Ethiopian resistance were defeated. In April 1936, Ethiopian King Haile Selassie went to the League of Nations to ask for help, but the League had no army to attack Mussolini’s.

Emboldened by the ineffectiveness of world opinion, the Italian occupation of Ethiopia was brutal. In February 1937, in response to an attempted assassination on the new Italian viceroy in the capital city, Addis Ababa, Italians went on a three-day killing spree to exact vengeance on the Ethiopians. At least 20,000 were murdered, including Ethiopian intellectuals who had already been imprisoned in wretched conditions. As we’ll see, such atrocities were typical of the racism inherent in fascist regimes, who thought that using such terror was the only way to “teach a lesson” to “inferior” peoples. However, the Italians would not succeed in their attempt to conquer Ethiopia. Persistent fighting among the Ethiopian resistance continued for the next five years before they were joined by British forces and the Italians were forced to leave Ethiopia in 1941.

After losing most of its Latin American colonies in the early nineteenth century, Spain fell into decades of civil wars. By the time Spain lost the Philippines, Cuba, and Puerto Rico to the United States in 1898, the Spanish Empire was less stable and poorer than several of its former territories such as Argentina and Chile. In the early years of the new century, Spanish workers were inspired by socialism and anarchism, the belief that taking down all forms of repression would liberate the natural socialist and communal tendencies of humanity. Many found fault with the Catholic Church, which received government funds to educate and provide welfare for the poor but was seen as ineffective and hypocritically enjoying its own riches by the starving, illiterate, and landless peasants and proletarians.

By 1931, even the middle class had had enough of Spain’s backwardness. The king abdicated—another victim of the crisis of the Great Depression—and a Spanish Republic was established. A new Spanish constitution formed a presidential-parliamentary government with proportional representation, much like the Weimar Republic in Germany. Agrarian reform and limiting the temporal power of the Catholic Church divided the Spanish people, and the liberals and socialists lost control of the government in 1933, when conservatives won the national elections. Rebellions by radical miners in northern Spain in 1934 led to repression and the imprisonment of thousands, leading to the formation of a “Popular Front” government in February 1936 after very close elections.

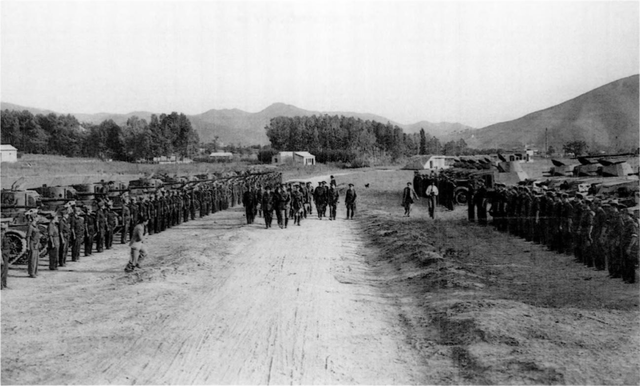

Soviet leader Joseph Stalin ordered the world’s communist parties to join anti-fascist Popular Front coalitions. The Spanish Popular Front government was a coalition of socialist, anarchist, and workers’ parties who united as “Spanish republicans” seeking to preserve and extend liberal reforms. However, when the new government rolled out agrarian reforms and began suppressing the church, street fighting and assassinations led to a fascist-supported military coup orchestrated by General Francisco Franco in July 1936. Although Franco’s nationalist Falangist took control of northern and western Spain, the fascists were stopped in the region around Madrid and Barcelona by socialist and anarchist workers who had been armed by the Republican government. A bloody civil war commenced.

Hitler and Mussolini immediately sent weapons, troops, and air support to Franco, while Stalin supported the Republic. The leading European democracies—Great Britain and France—declared neutrality, while the United States chose once again to try to stay out of Europe’s disputes. Individual British, French, and American volunteers arrived to fight for the Republic, hoping to make Spain “the graveyard of fascism.” The young democratic socialist author George Orwell, for instance, joined the anti-fascist cause, as did the American members of the “Abraham Lincoln Brigade,” a motley crew of various internationalists, including African Americans and Jews, as well as everyone from anarchists, to socialists, to communists. Although not part of the U.S. Army, it was arguably the first time that Americans would fight in a truly desegregated unit. However, even before Franco and the nationalists finally defeated the Republic in April 1939, Stalin had pulled Soviet advisors out of Spain and abandoned the Popular Front strategy. Francisco Franco remained the authoritarian dictator of Spain until his death in 1975.

Questions for Discussion

- What were the main causes of World War II?

- How did racism play an early role in fascist expansionism?

- Why did Stalin support the Spanish Popular Front?

Why this reaction from the victors of World War I? By the 1930s and the Great Depression, the French, British, and Americans were wondering what “winning” the Great War had really meant. The deaths of millions and the wounding of millions more did not seem worth repeating. The Germans, on the other hand, had been humiliated by the peace and were now led by a man, and a party, that claimed that they could have won if they had not been “stabbed in the back” by liberals, social democrats, socialists, communists, and Jews. And unfortunately, many fascist sympathizers in the democracies agreed with this assessment: that corrupt politicians and capitalists, as part of a Jewish-led cabal, had been the only ones to benefit from leading their countries into a useless war. They also hypothesized that this cabal was behind the socialist and communist revolutionary sentiment. There was truth in the observation that bankers and capitalists had profited from the war, but there was no evidence of a conspiracy. The fact that public opinion descended into fantastic conspiracy theories is a testament to the psychological effect of the worldwide economic crisis on a fearful humanity.

Hitler’s foreign policy, which he had announced to the world in his book Mein Kampf in 1923, was based on the idea of absorbing regions with German-speaking populations into his Greater Reich. Lebensraum, living space, for Aryans would be taken from the Slavic peoples of Eastern Europe. In March 1938, Germany annexed Austria, its ally in the previous war and homeland of Hitler, with the support of most Austrians. Once again, Great Britain and France failed to respond. Hitler set his sights on the Sudetenland, an ethnically German region of Czechoslovakia. In October 1938, the British and French leaders, alarmed but still anxious to avoid war, attended a diplomatic conference in Munich, where they agreed that Hitler could annex the Sudetenland in return for a promise to stop all future German aggression. They were desperate to believe the Führer could be appeased, but in March 1939, German troops rolled into the rest of Czechoslovakia. The Czechoslovak government had not even been invited to the conference in Munich; despite being the only democracy standing in Central Europe by 1938, they were betrayed by the appeasement policy of their fellow democracies.

Nor were the democracies moved by Nazi excesses against the Jews in Germany. In November 1938, after a German diplomat was assassinated by Herschel Grynszpan, an exiled Polish Ashkenazi Jew living in France, the Nazi government allowed a massive outpouring of violence against Jews and Jewish-owned businesses. German, Austrian, and Czech mobs murdered nearly a hundred Ashkenazim Jews, publicly humiliated thousands, and burned thousands upon thousands of businesses and synagogues. 30,000 Jewish men were arrested. There was a subsequent spike in suicide among members of the Jewish community as well. The infamous Nazi-militia, the “Storm Detachment” (Sturmabteilung), also known as the “Brownshirts,” were active participants in the violence. The Nazi-sponsored violence became known as Kristallnacht, “the Night of Broken Glass.” Many people in the democracies were outraged, thinking that such a pogrom was only impossible in a civilized nation like Germany. However, no government took action against Hitler, nor did any country accept Jewish refugees—anti-Semitism was all too common in most “civilized” countries.

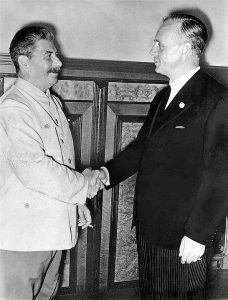

All of this was happening as Stalin was still supporting the Spanish Republic, hoping that the democracies would join in a struggle against rising fascism. When they instead appeased Hitler, Stalin concluded that the capitalists perceived Hitler as a bulwark against the communist Soviet Union rather than as a threat to their own territories and interests. The Soviet premier changed his diplomatic strategy and on August 23, 1939, signed a Non-Aggression Pact with Germany, as he feared the Soviet Army was not yet strong enough to fight an already mobilized German force. By that time, Hitler had set his sights on “liberating” the German-speaking population in Poland and their territory. German troops poured across the border on September 1, 1939. The world learned of the secret agreement to divide Poland included in the Nazi-Soviet Pact when Stalin sent his armies into eastern Poland three weeks later.

Questions for Discussion

- Why did the European democracies try to appease Hitler?

- Was Stalin wrong to sign a non-aggression pact with Germany?

The Road to War in East Asia

As described in the previous chapter, the government ruling in the name of Japanese Emperor Hirohito also shifted toward fascism after the invasion of Manchuria in 1931 and the establishment of the puppet state Manchukuo in northeast China and Inner Mongolia. Manchukuo provided Japan with the benefits of an imperial colony: raw materials for Japanese industries that were not available on the islands of Japan and a captive market for Japanese goods. The Japanese military also justified their conquests by claiming they were liberating Asia from European colonialism. Not all the Asian territories they invaded, however, were happy to become part of the Japanese “Greater East Asian Co-Prosperity Sphere.”

China was still in the midst of a civil war between the Kuomintang and the Chinese Communist Party, and the Kuomintang leader and president of the Republic, Chiang Kai-shek, ignored the Japanese threat in northern China until it was too late. Chiang appealed to the League of Nations for assistance against Japan. The United States supported the Chinese protest, and after a six-month investigation, the League found Japan guilty and demanded the return of Manchuria to China. The diplomats of the League had no way to enforce their ruling, of course. Japan ignored the demand and simply withdrew from the League of Nations. Japanese diplomatic isolation further empowered radical military leaders who could point to Japanese military success in Manchuria and compare it to the diplomatic failures of the civilian government. The military took over Japanese policy. In the military’s eyes, the conquest of China would not only provide for Japan’s industrial needs; it would secure Japanese supremacy in East Asia.

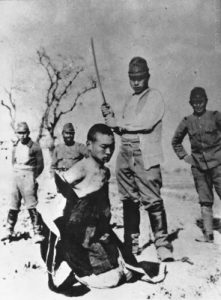

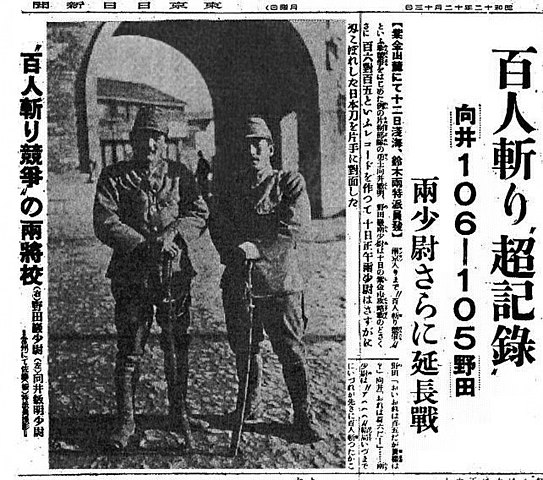

Japan launched a full-scale invasion of China on July 7, 1937, and routed the forces of the Chinese National Revolutionary Army led by Chiang Kai-shek. The broken Chinese army gave up Beijing to the Japanese on August 8, Shanghai on November 26, and the Nationalist capital, Nanjing, on December 13. In the first six weeks after capturing the capital, Japanese troops killed half of the city’s population of 600,000. They began by executing 90,000 Chinese Army deserters, who they despised for surrendering, and then moved on to civilians. Japanese troops raped up to 100,000 women and girls and then shot or bayonetted most of them in what is now recognized as one of the worst atrocities of World War II. To pacify the rest, the Japanese distributed opium and heroin to the captive population. Like the Italian fascists in Ethiopia and the German Nazis in occupied Europe, the Japanese military felt themselves to be superior to the conquered peoples and believed that only terror could subdue the civilian population.

Hoping to halt the invading enemy, Chiang Kai-shek adopted a scorched-earth strategy of “trading space for time.” His Nationalist government retreated inland, burning villages and destroying dams—in the process, killing more Chinese peasants than the Japanese had killed in the atrocities in Nanjing. Chiang established a new capital deep in the interior at the Yangtze River port of Chungking. Although the Nationalists’ scorched-earth policy hurt the Japanese military effort, it alienated Chinese civilians and became a potent propaganda tool of the emerging Chinese Communist Party.

When news of the “Rape of Nanjing” first reached the West, many were skeptical because the violence was so extreme. However, U.S. missionaries and European businessmen had established an “International Safety Zone” in Nanjing during the atrocities, which saved 200,000 Chinese civilians and documented the Japanese actions. Curiously, the effort was led by the German businessman John Rabe, at the time a card-carrying member of the Nazi Party. Eyewitness accounts written by Europeans and Americans were published in American newspapers, along with photographic evidence, and the brutality of Japanese imperialism began to sink in. However, no one was going to declare war on Japan to save the Chinese.

The United States lacked both the will and the military power to oppose the Japanese invasion and even continued to sell oil and scrap iron to Japan. The Japanese Imperial Army was a technologically advanced force consisting of 4,100,000 men and 900,000 Chinese collaborators armed with modern rifles, artillery, armor, and aircraft. By 1940, the Japanese navy was the third largest and among the most technologically advanced in the world. Still, Chinese Nationalists lobbied Washington for aid. Chiang Kai-shek’s popular wife, U.S.-educated Soong May-ling, known to Americans as Madame Chiang, led the effort. In contrast to her gruff husband, Madame Chiang was charming and able to use her knowledge of American culture and values to garner support for Chiang and his government. But although the United States denounced Japanese aggression, it took no action. As the Nationalists fought for survival, the Chinese Communist Party was busy accumulating supporters and supplies in the northwestern Shaanxi Province. Mao Zedong recognized the power of the Chinese peasant population and began recruiting from the local peasantry, capitalizing on the outrage caused by both the Nationalist failure to prevent Japanese invasion and its scorched-earth retreat. Mao gradually built his force from a meager seven thousand survivors at the end of the Long March in 1935 to a robust 1.2 million members by the end of World War Two.

Questions for Discussion

- What would you say to Japanese leaders today who claim the Rape of Nanjing never happened?

- Do you think Chiang Kai-shek was an effective leader of the Kuomintang?

1940–1942: Axis Conquests in Europe and Asia

Two days after the German Wehrmacht invaded Poland on September 1, 1939, Britain and France declared war and began mobilizing their armies. The war planners hoped the Poles would be able to hold out for three to four months, enough time for the Allies to intervene. Poland fell in three weeks, partly due to the Russian invasion in the east and partly due to a new form of warfare. The German army, anxious to avoid the rigid, grinding war of attrition in the trenches of World War I, had built its new army for speed and maneuverability. German strategy emphasized the use of tanks, planes, and motorized infantry to concentrate forces, smash front lines, and wreak havoc behind the enemy’s defenses. It was called Blitzkrieg, “lightning war.”

After conquering eastern Poland, Stalin’s armies shifted focus to occupying the Baltic states (Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia) and to invading Finland. The Soviet leader was planning to reestablish the borders of the former tsarist Russian Empire. However, the invasion of Finland met stubborn resistance and winter—the conflict ended with the Finns losing only a bit of territory on their southeastern borders.

Meanwhile, after the fall of Poland, France and Britain braced for the inevitable German attack. In April 1940, the Germans quickly conquered Denmark and Norway in an effort to prevent the British naval blockade that had been so key to the German defeat in World War One. The following month, Hitler launched his blitzkrieg into Western Europe through the Netherlands and Belgium to avoid well-prepared French defenses along the French-German border. Poland had fallen in three weeks; France lasted only a few weeks more. By June, Hitler was posing for photographs in front of the Eiffel Tower. In another propaganda victory, Hitler made the French diplomats sign their surrender in the same railroad car used for the German surrender in the First World War.

Germany split France in half, occupying the north and allowing a collaborationist government to form in Vichy to govern the south and the French colonies. Led by the “Hero of Verdun,” Marshal Philippe Pétain, the Vichy regime sought to reorganize France along authoritarian fascist lines. Significant support for Germany by the French right was one of the reasons for their defeat in June 1940. Many in France had also abandoned democracy and welcomed the demise of the Third Republic. If the future held a German-dominated Europe, they reasoned, then it would be better for France to collaborate as partners rather than as subjects in a new Nazi empire. Although this rationalization fit into the scheme proposed by German propaganda, Hitler would never allow a full partnership with any of the conquered peoples.

With France under control, Hitler turned to Britain. Operation Sea Lion, the German invasion of the British Isles, required air superiority over the English Channel. From June until October 1940, the German Luftwaffe fought the Royal Air Force for control of the skies. Despite having fewer planes, British pilots won the so-called Battle of Britain, saving the islands from invasion and prompting the new prime minister, Winston Churchill, to declare, “Never before in the field of human conflict has so much been owed by so many to so few.”

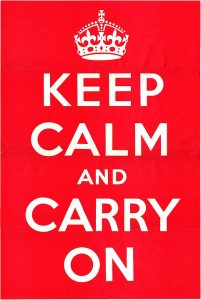

But if Britain was safe from invasion, it was not immune from ongoing air attacks. Frustrated by losing the Battle of Britain, Hitler began a bombing campaign against cities and civilians. The Blitz, as the British came to know the nightly bombing raids on London, killed at least 40,000 civilians. Population centers like Bristol, Cardiff, Portsmouth, Plymouth, and Southampton and industrial cities like Swansea, Belfast, Birmingham, Coventry, Glasgow, Manchester, and Sheffield were also targeted for heavy bombing. The Royal Air Force defended the cities as well as they could, and British industrial production, which had been moved out of major cities, was unaffected by the air attacks. The British people, encouraged by Churchill, kept calm and carried on.

In anger, Hitler and his vice chancellor, Herman Göring, began a policy of hitting London every day to try to break the will of their enemy. Beginning on September 7, 1940, London was bombed every night for 56 days, including a large daylight attack on September 15. British morale failed to break, and Germany eventually shifted to targeting Atlantic shipping and bombing port cities in an attempt to starve the enemy. When the port of Clydebank in Scotland was bombed in March 1941, only 7 of 12,000 houses escaped damage. But the Germans failed to gain complete air superiority, partly due to the deployment of RADAR (Radio Detection and Ranging) by the British. The technology had been developed in the 1930s and was advanced and finally perfected by Britain in the early 1940s. It would be offered to the Americans in exchange for financial and industrial support as the two nations strengthened ties to “defend democracy” even before U.S. involvement in the war.

Nazi ideology considered the English as racial equals, and Hitler hoped that Great Britain would eventually join a crusade against Bolshevism. However, Nazi doctrine focused on establishing German lebensraum in Eastern Europe, enslaving the lesser Western Slavic peoples to work for the Aryans. Hitler had always planned on breaking his 1939 nonaggression pact with Stalin and invading the Soviet Union. First, German armies invaded the Balkans and set up puppet regimes in Hungary and Romania, giving them a wider front for attacking the Soviets. However, Mussolini, playing catch-up with his Axis partner, had sent his troops to conquer Greece from Albania, which Italy had acquired in April 1939. The Greeks not only defended themselves but pushed the Italians back into Albania; Hitler had to bail out Mussolini and invade, sending his armies into Yugoslavia and Greece.

In June 1941, German forces crossed into the Soviet Union in a massive surprise attack. Operation Barbarossa was the largest land invasion in history. France and Poland had fallen in weeks, and Germany hoped to use the same Blitzkrieg tactics to break Russia before the winter. The German military caught the Red Army and Stalin unprepared and quickly conquered enormous swaths of land and captured nearly three million prisoners. But Russia was too big. After recovering from the initial shock of the German invasion, Stalin moved his factories east of the Urals, out of range of the Luftwaffe. He ordered his retreating army to adopt a scorched-earth policy, destroying food, rails, and shelters to slow the advancing German army.

The German army split into three forces and reached the gates of Moscow and Leningrad, but their supply lines stretched thousands of miles. While Soviet infrastructure had been destroyed, partisans—including skilled snipers—harried German lines, and the brutal Russian winter arrived. Germany had won massive gains, but the winter found German troops exhausted and overextended. In the north, the German army intentionally starved a million and a half people in Leningrad to death during an 827-day siege that has since been called a genocide by some historians. In the center, on the outskirts of Moscow, the German army faltered and fell back after a three-month battle that killed a million people.

Questions for Discussion

- How was Hitler able to surprise Stalin with Operation Barbarossa?

- Why was the Blitzkrieg strategy that had worked so well in Europe less successful in Russia?

While Hitler marched across Europe, the Japanese Empire continued their war in the Pacific. In 1939, the United States dissolved its trade treaties with Japan, and the following year, America cut off supplies of war materials by embargoing oil, steel, rubber, and other vital goods. Instead of being starved into submission, Japan’s resource-challenged military accelerated invasions across East Asia to sustain its war effort. The Japanese took control of French Indochina (now Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos) from the Vichy Regime and began threatening the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia) after the Netherlands was occupied by Germany. Diplomatic relations between Japan and the United States collapsed. The United States demanded that Japan withdraw from China and the French and Dutch territories; Japan considered the oil embargo a de facto declaration of war.

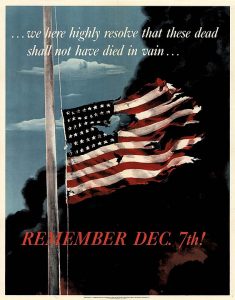

Japanese military planners, believing that American intervention was inevitable, planned a coordinated Pacific offensive to neutralize the United States and other European powers and provide time for Japan to complete its conquests and fortify its positions. On the morning of December 7, 1941, the Japanese launched a surprise air attack from their carriers on the American naval base at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. Japanese military planners hoped to destroy enough battleships and aircraft carriers to cripple American naval power for years. The Japanese destroyed or seriously damaged eight battleships (four sank), three cruisers, three destroyers, and 180 aircraft and killed 2,403 American servicemen and wounded a thousand. 353 Japanese bombers, fighters, and torpedo planes wiped out nearly the entire U.S. Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor. Luckily for the U.S. Navy, its aircraft carriers were out on maneuvers and not at port during the attack.

The position of American isolationist politicians almost entirely collapsed after Pearl Harbor. Much of the political elite in the United States were now pro-war, especially as Japan also assaulted Hong Kong, the Philippines (an American commonwealth), and other American holdings throughout the Pacific. This is not to say public sentiment on the mainland cared much about the Pacific territories or the naval base on Hawaii. Indeed, public sentiment remained against American entry into the conflict. However, Franklin Roosevelt pointed specifically toward Pearl Harbor as a symbolic turning point, as he called December 7 “a date which will live in infamy” and called for a declaration of war, which Congress approved within hours. In reprisal, Germany and Italy declared war on the U.S. on December 11. Within a week of Pearl Harbor, the United States was at war with the entire Axis, turning two previously somewhat separate conflicts into a true world war.

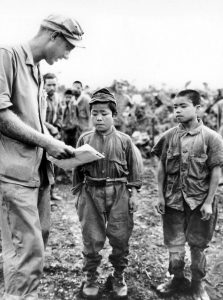

After Pearl Harbor, Japan conquered the American-controlled Philippine archipelago. After running out of ammunition and supplies, the garrison of American and Filipino soldiers surrendered. The prisoners were marched eighty miles to a Japanese prisoner-of-war camp without food, water, or rest. Ten thousand died on the Bataan Death March.

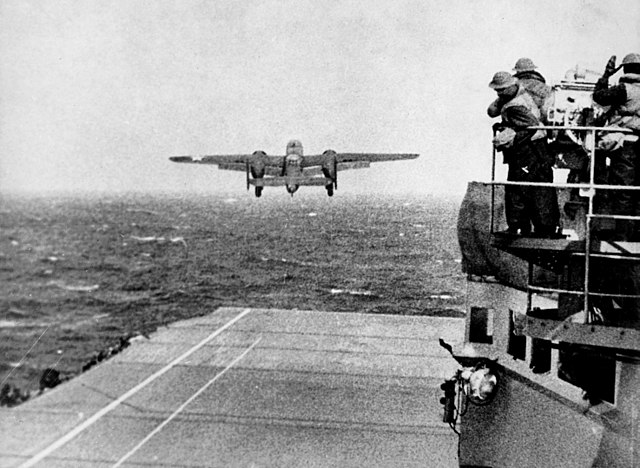

Although Japan hoped the United States would be unable to respond quickly, four months after Japan’s surprise attack on Hawaii, in April 1942, the U.S. Army Air Force bombed Tokyo using sixteen B-25 medium-range bombers launched from an aircraft carrier in the Pacific. The man who planned and led the raid, Lt. Col. Jimmy Doolittle, said of the plan, “The Japanese people had been told they were invulnerable…An attack on the Japanese homeland would cause confusion in the minds of the Japanese people and sow doubt about the reliability of their leaders.” Doolittle added, “There was a second and equally important psychological reason for this attack: Americans badly needed a morale boost.”

However, Franklin Roosevelt and Winston Churchill understood that Germany was a more immediate threat. In 1940 and 1941, the United States had already begun providing financial and material support to Great Britain and to Russia, as it had previously in World War I. Britain had stood alone militarily in Western Europe, but the British people refused to be conquered, and American supplies bolstered their resistance. Roosevelt and Churchill met in April 1941 and declared the Atlantic Charter—a pledge that claimed to defend freedom and democracy from fascism. It did not seem to matter to either that legal discrimination by race was still common practice in both the United Kingdom and the United States, based entirely on legislation that very much resembled the Nuremburg Laws of Nazi Germany.

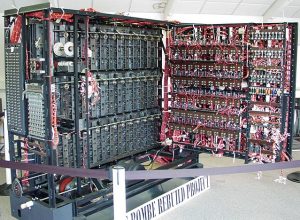

After the U.S. officially entered the war, Hitler unleashed U-boat “wolf packs” into the Atlantic Ocean with orders to sink anything carrying aid to Britain. After losing thousands of merchant ships in 1942 and early 1943, British and U.S. tactics and technology won the Battle of the Atlantic. British code breakers at Bletchley Park led by Alan Turing cracked Germany’s Enigma radio cryptography. The surge of intelligence, dubbed Ultra, coupled with naval convoys escorted by destroyers armed with sonar and depth charges and air support, gave the advantage to the Allies. By mid-1943, Hitler’s navy was losing ships faster than they could be built. Soon the wolf pack was sheltering in a defensive crouch in the harbors of occupied Europe.

Questions for Discussion

- Did Japan make a strategic error in attacking the United States?

- Reflect on the technological developments that were accelerated by the war.

Allied Victories

When Hitler renewed his invasion of the Soviet Union in the summer of 1942, he focused on conquering the breadbasket and oil fields of southern Russia. The Blitzkrieg again brought rapid success, but again got too far ahead of its supply lines. Although the strategy included sophisticated tanks, armored troop carriers, and dive bombers, the Germans still used horse-drawn wagons to bring up food, ammunition, and spare parts to the advancing armies. As the advance slowed, Axis armies arrived at the new industrial city on the Volga River, Stalingrad. Hitler badly wanted to conquer and wipe out Stalin’s namesake city, and the Soviet premier was just as determined to defend it. In late 1942, the two armies bled themselves to death in the destroyed city, fighting house to house in a five-month battle that killed nearly two million people on both sides. Stalin placed his trust in General Georgy Zhukov, who planned a brilliant Soviet pincer move, cutting off the German 6th Army in Stalingrad. When his army was forced to surrender in February 1943, Hitler was apoplectic in his anger, and his generals began to doubt that he had the strategic brilliance he showed in the previous years.

The Germans planned to follow up with renewed attacks to get at Soviet oil, but their battle with the Red Army at Kursk turned the course of the war definitively to the Soviets. Zhukov correctly guessed the German strategy and fortified Kursk while massing armies to the north and south. After the greatest tank battle in world history, Zhukov unleashed another pincer move, and the Germans retreated from battle as quickly as they could. The Red Army began rolling westward, putting the Germans permanently on the defensive for the remainder of the war. More than any other Ally, the Soviet Union was most responsible for defeating Hitler, but at great sacrifice. Twenty-five million Soviet soldiers and civilians died, and roughly 80 percent of all German casualties during the war came on the Eastern Front.

Allied victories in North Africa in 1942 also reversed Axis gains. The Germans and Italians had been threatening British Egypt since late 1940 and, led by the capable General Erwin Rommel, seemed to be on the brink of victory in the spring of 1942. Hitler’s decision to invade southern Russia was based on the expectation that the Middle East would soon fall into Axis hands. In November, the first American combat troops entered the European war, landing in French Morocco, where French forces previously allied with the Vichy Regime quickly switched sides and joined the struggle to defeat the Axis. The Americans pushed the Germans and Italians eastward while the British, after defeating Rommel at El Alamein in Egypt, began rolling the Axis armies back to the west. By early 1943, the Allies had pushed Axis forces into Tunisia and then out of Africa.

Meanwhile, the Americans gradually stopped Japanese expansion in the Pacific. In the summer of 1942, American naval victories at the Battle of the Coral Sea and the aircraft carrier duel at the Battle of Midway crippled Japan’s Pacific naval operations. The battles were the first time two naval fleets engaged one another by air and not by sea. At Coral Sea, the U.S. Navy blocked the Japanese threat to Australia; Midway eliminated Japan’s advance toward Hawaii while sinking three Japanese aircraft carriers that were irreplaceable, as Japan did not have the industrial capacity to replenish its fleet. The U.S., in contrast, was producing ships almost by the day.

To dislodge Japan’s hold over the Pacific, the U.S. began attacking island after island, bypassing the strongest but seizing those capable of holding airfields to continue pushing Japan out of the region. Combat was vicious. At Guadalcanal, Japanese soldiers launched suicidal charges rather than surrender. Many Japanese soldiers refused to be taken prisoner or to take prisoners themselves. Such tactics, coupled with American racial prejudice, turned the Pacific Theater into a much more brutal and barbarous conflict than battle in the European Theater.

In January 1943, President Roosevelt and Prime Minister Churchill met at Casablanca to discuss the next step of the European war. The meeting leaders also declared that they expected nothing short of unconditional surrender from the Germans—to assure Stalin, who still did not trust the Allies to keep their word. At Casablanca, Churchill convinced Roosevelt to chase the Axis up the Italian peninsula, into the “soft underbelly” of Europe. Stalin preferred a cross-Channel invasion of France, but the British and Americans were not yet prepared in 1943. In July, Allied forces led by General Dwight Eisenhower crossed the Mediterranean and landed in Sicily. The Italian king dismissed and arrested Mussolini, who escaped with Germany’s help and established a fascist government in northern Italy. The south, however, switched sides and fought alongside the Allies for the rest of the war. However, the advance northward toward Europe’s “soft underbelly” turned out to be much tougher than Churchill had imagined. Italy’s narrow, mountainous terrain and Mussolini’s newly formed fascist state gave the defending Axis the advantage. Movement up the peninsula was slow, and in some battles, conditions returned to the trench-like warfare of World War I as the German armies fell back to new defensive positions, exhausting Allied forces in one battle after another. It would take nearly a year to capture Rome, and northern Italy was not liberated until the last weeks of the war in 1945.

Meanwhile, the U.S. Army Air Force (USAAF) sent thousands of bombers to England and North Africa in preparation for a massive strategic bombing campaign against Germany—another move to assure Stalin the Allies were opening a “second front” against Germany. The Allies’ plan was to bomb German cities around the clock. Initially, U.S. bombers focused on destroying German ball-bearing factories, rail yards, oil fields, and manufacturing centers during the day because the U.S. was reluctant to target civilians in terror bombings. However, after the London Blitz, the British felt no compunction against retaliating in kind and carpet-bombed German cities at night. By the end of 1944, the Americans joined the British in the same strategy, bombing urban industrial targets despite massive civilian casualties. The joint RAF-USAAF bombing of the industrial city Dresden in February 1945 dropped 3,900 tons of high explosives on the city, causing a firestorm that killed 25,000 civilians.

Flying in formation, the air squadrons initially flew unescorted, since many believed that “flying fortress” bombers equipped with defensive firepower flew too high and too fast to be attacked. However, advanced German technology allowed fighters to easily shoot down the lumbering bombers. German fighter planes shot down almost half of American and British aircraft until long-range escort fighters were developed that allowed the bombers to hit their targets while fighters confronted opposing German aircraft.

Historians still debate the effectiveness of the Allied bombing campaign against both Germany and Japan and the overall usefulness of bombing civilians in World War II. The Germans actually increased production of war materiel during the war, relocating factories and streamlining production. German and Japanese civilians, like the Londoners in 1940, learned to live with aerial attacks instead of rising up to overthrow their own governments and sue for peace. Critics of terror-bombing argue that targeting civilians rarely results in surrender and instead often stiffens a country’s resolve to fight on and inflict the same terror on its foe.

In the wake of the Soviet victory at Stalingrad, Roosevelt, Churchill, and Stalin met in Tehran in November 1943. Dismissing Africa and Italy as a sideshow, Stalin demanded that Britain and the United States invade France to support the Soviet advance on the Eastern Front. Churchill was hesitant, but Roosevelt was eager. The invasion was tentatively scheduled for May 1944. The leaders also began post-war planning, considering the best ways to prevent another world war and Great Depression. The Allies had already begun calling themselves the “United Nations,” especially as Latin American republics and other countries began joining the fight against the Axis. In April 1945, diplomats gathered in San Francisco to design a way for the United Nations to address world problems in a post-war world.

To avoid another Great Depression and to reconstruct war-torn nations, in 1944, the Allies also sent representatives to the Bretton Woods resort in New Hampshire to forge new international financial, trade, and developmental relationships. The results of both conferences will be discussed below, but it is important to notice that both international meetings were held in the United States. Americans had become convinced that isolationism was no longer a practical foreign policy, and the world recognized that the U.S. was going to be instrumental in a post-war effort to keep the peace.

Questions for Discussion

- How did the different wartime experiences of the Allies influence the goals of the “Big Three” leaders, Stalin, Churchill, and Roosevelt?

- If terror-bombing civilian populations is ineffective, why did everyone continue doing it?

The Conclusion

On the same day the American army entered Rome, American, British, and Canadian forces launched Operation Overlord, the long-awaited invasion of France. D-Day, as it became known, was the largest amphibious assault in history. American general Dwight Eisenhower was uncertain enough of the attack’s chances that the night before the invasion, he wrote two speeches: one for success and one for failure. Using over 5,000 landing and assault craft, about 160,000 men crossed the English Channel on D-Day. The Allied landings at Normandy were successful, and by the end of the month, 875,000 Allied troops had arrived in France. Paris was liberated in late August.

Allied bombing sorties intensified, continuing to level German cities and reduce Axis industrial capacity. The Royal Air Force estimated that the Allies destroyed more than half of the “built up areas” in seven of the ten German cities with more than 500,000 residents. The RAF’s goal, similar to that of Germany during the Blitz, was for bombing to be “focused on the morale of the enemy civil population and in particular of the industrial workers.” The USAAF flew over 750,000 bomber sorties and dropped nearly a million and a half tons of bombs. Up to five hundred thousand German civilians were killed by allied bombing.

The Nazi armies were crumbling on both fronts. Hitler tried to turn the war in his favor in the west. The Battle of the Bulge in December 1944 and January 1945 was the largest and deadliest single battle fought by U.S. troops in the war. The desperate Germans failed to drive the Allies back from the Ardennes forests to the English Channel, but the delay cost the western-front Allies the winter. The invasion of Germany would have to wait, while the Soviet Union continued its relentless push from the east, ravaging German populations in retribution for German war crimes. German counterattacks failed to prevent the Soviet advance, and 1945 dawned with the end of European war in sight.

In February 1945, Roosevelt, Churchill, and Stalin met again at Yalta, located on the Crimean Peninsula in the Black Sea. Roosevelt and Churchill were anxious for Soviet help in defeating Japan; the atom bomb was months away from being tested, and no one knew whether it would work. Stalin agreed to join the fight in Asia against Japan three months after peace was declared in Europe.

The three leaders discussed their own long-range strategic interests at Yalta. Stalin, whose country had sacrificed the most in the war, insisted on defending the Soviet Union from future invasion by occupying Eastern Europe. Remembering British and U.S. support of the White Russians in the Civil War he had fought in the 1920s, Stalin distrusted his temporary allies against Germany. Partly to destabilize the capitalist nations he distrusted and partly because he was still a dedicated revolutionary, Stalin also wanted to continue to promote communism around the world.

Churchill, for his part, continued to believe that the colonial European empires in Africa and Asia should continue as before (the French also supported this position). Roosevelt’s main interest was maintaining the economic boom that had pulled the United States out of the Great Depression through free international trade. The war had put people back to work, and the nation was at near full employment. Since the U.S. was not bombed, American industry was in a position to supply the world and American firms to dominate world markets. Although the three nations shared the victory in World War Two, in the long run, the United States “defeated” its allies. The European empires Churchill hoped to save were ended by the 1960s with the independence of Asian and African colonies, and Stalin’s Soviet Union and domination of Eastern Europe dramatically collapsed in 1989–1991. Roosevelt’s position was the most successful in the long run. Free trade exists throughout the world and is currently embraced by industrially developing nations as a means for economic growth. However, nothing lasts forever: the United States is beginning to lose its position as the leader of the capitalist world—we will discuss this change in a later chapter.

Soviet troops reached Germany in January 1945, and the Americans crossed the Rhine in March. In late April, American and Soviet troops met at the Elbe River while the Soviets pushed relentlessly to reach Berlin first and took the capital city in May. A few days before their arrival, Hitler and his high command committed suicide in a city bunker. Germany was conquered and the European war was over.

A changed set of Allied leaders met again at Potsdam, Germany. Of the “Big Three” who had met at Yalta, only Stalin was at Potsdam for the whole conference. Roosevelt had died of natural causes in early April, and Churchill was replaced by new Prime Minister Clement Atlee in the early days of the meeting when his Conservative Party was defeated at the polls by the Labour Party. The leaders agreed that Germany would be divided into pieces according to the current Allied occupation, with Berlin likewise divided.

Questions for Discussion

- D-Day is an iconic moment for Americans. What do you think similar moments would be for Britain and the Soviet Union?

- Why did the U.S. and U.S.S.R. race to reach Berlin?

The Holocaust

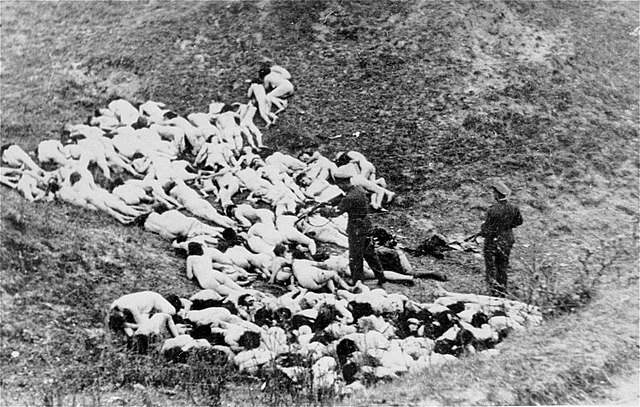

We have already seen the application of fascist ideology in murderous atrocities against “inferior people” by the Italians in Ethiopia and the Japanese in China in the early years of World War II. Nazi anti-Semitism had revealed its violent aspects in Kristallnacht in 1938 but was even more viciously applied once German armies began conquering Eastern Europe. Ten percent of Poland’s pre-war population was Jewish, about 3 million people, who had been subjected to discrimination by the authoritarian Polish government in the 1930s. However, under German occupation, Jews were forced into overcrowded ghettoes in certain Polish cities. The areas captured by the Wehrmacht in the western Soviet Union during Operation Barbarossa added millions of Jews to Nazi-occupied Europe. While Hitler and his government had briefly considered sending Jews to far-off exile outside of Europe, ultimately the Führer decided that their physical elimination was necessary—a “Final Solution” to the “Jewish Problem.” Mass shootings by specialized troops called Einsatzgruppen accompanied the invasion of the Soviet Union. In October 1941, outside of the Ukrainian capital of Kiev, Jewish men were forced to dig mass pits in the Babi Yar ravine into which they and their families were herded naked and shot by Einsatzgruppen and Ukrainian fascists. Babi Yar was among the largest mass shootings of the war.

During Operation Barbarossa, the Germans also captured millions of Soviet troops, who they herded into prisoner-of-war camps and basically starved to death. At least two million Soviet soldiers died this way. Non-Russians in these camps, Balts and Ukrainians, were given the option to join special guard units and collaborate with the Germans. As the mass shootings took their psychological toll on German soldiers and guardsmen, these non-Germans were called upon to murder Jewish civilians and patrol the ghettoes and concentration camps.

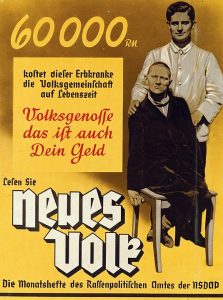

Even before the war began, “mercy killing” had become a Nazi policy in German psychiatric and mental institutions, where those with physical and mental disabilities were denied care and murdered. Shortly after defeating Poland, Hitler ordered the elimination of all “defectives.” The staffs of these hospitals experimented with mass killing through carbon monoxide being pumped into buses and discovered a new use for a rodent repellent called “Zyklon B.” These methods were soon applied at specially built extermination camps in Eastern Europe, the first opening in early 1942. Jews were packed into railroad cattle-cars and taken to these camps, where they were told that they were going to “showers,” but instead were sealed in and gassed. “Work Jews” were assigned to cremate the remains, until they too were exterminated.

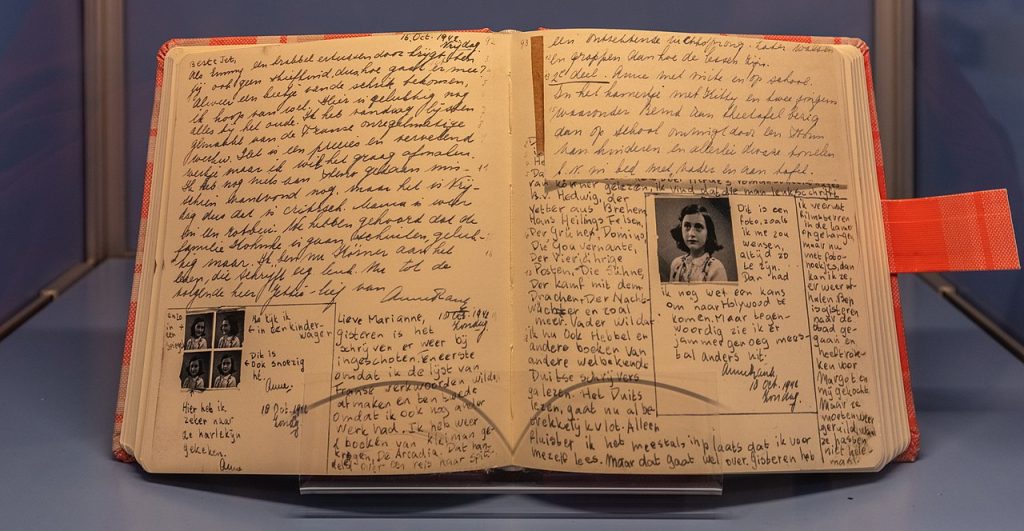

With the establishment of the extermination camps, the Germans began “relocating” Jews from France and other occupied areas in Western Europe by rail to the East. In all countries of occupied Europe, some Jews were saved by their Christian neighbors, hidden in attics, barns, and even churches and monasteries until the end of the war. But even then, they were not always safe. The German-Jewish Frank family had moved to the Netherlands to escape the Nazi regime in late 1933. They had hoped that Holland would be a safe haven in a new European war, since it had remained neutral in World War One. However, the Germans occupied the country along with Belgium and France in 1940 and, by 1942, were sending Jews in transports to the East. The Frank family was able to hide in an annex with others, supplied with food and news of the war by a group of Dutch friends active in the underground resistance. However, they were discovered by German authorities in August 1944 and sent off to the camps. Young Anne Frank had kept a diary during their two years in hiding, and her father, who survived the war, published it in 1947. Although Anne Frank’s diary has become one of the most important records of the Holocaust, the Germans themselves also kept detailed records of their actions against Jews, Romani, homosexuals, socialists, communists, and others. New details emerge frequently of the extent and reach of the Holocaust, concentration camps, and slave labor.

However, during the war itself, it was difficult for the Allies to believe rumors and reports they were receiving of atrocities, mass executions, and death camps in Nazi-occupied Europe. Polish resistance fighter Jan Karski was smuggled into the Warsaw ghetto and a transit camp in order to witness how the Jews were treated. He saw teenage Hitler Youth members walking into the ghetto to casually murder a Jew or two and Jewish families destined for extermination packed into rail cars. It was difficult for Roosevelt, Churchill, and others to believe his report, given in person in Washington and London. When Karski described what he had seen to U.S. Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter, a Jewish American, Frankfurter replied, “I know you are telling the truth, but I don’t believe you,” expressing the world’s incredulity that the Germans could perpetrate such atrocities.

As the Allies pushed into Germany and Poland, they uncovered the full extent of Hitler’s genocidal policies. The Allies liberated elaborate camp systems set up for the imprisonment, forced labor, and extermination of the Jews and other “undesirables” including Romani (“gypsies”), socialists, communists, trade unionists, anarchists, other political prisoners and members of the resistance, individuals from the LGBT community, and pacifists. Allied officers often forced German civilians to visit the camps in their towns and regions in order to witness the consequences of Nazi and fascist ideology that the “other” must be eliminated. Since then, Germany has been forced to come to terms with this history, and German society has tried to confront the past honestly. This effort has been unusual: Turkish, Japanese, and especially American societies have failed to similarly address similar actions in their history. Europeans intentionally mass murdering other Europeans, and using industrial methods, was unacceptable. The atrocities of Europeans against colonized peoples in Africa, Asia, and the American West seemed more acceptable, and were rarely addressed, due to a legacy of institutionalized racism. But the violence was very real to Southeast Asians, Congolese, Native Americans, Indigenous Peoples, and Black Americans.

The attempted elimination of the entire Jewish population in Europe has had other geopolitical effects. The Holocaust seemed to prove the Zionist thesis correct that the Jews would never be safe unless they established their own homeland. This was achieved in Israel three years after the war ended in Europe—but not, as we shall see, without long-term consequences for the Palestinian Arabs and the rest of the Middle East. News of the death of six million Jews was especially difficult for Jewish Americans, who suddenly realized that they were nearly the last surviving remnant of an ancient people after their relatives and loved ones were murdered in Hitler’s camps. Previously, Jewish life had been centered in Poland and the Ukraine; now it was in the United States and Israel.

Questions for Discussion

- Why was the German killing of 11 million people in the Holocaust so difficult for people to believe?

- What do you think motivates people who insist the Holocaust didn’t happen?

Pacific War

As the Allies, especially the Americans, celebrated V-E (Victory in Europe) Day, they redirected their full attention to the still-raging Pacific War. In 1944 and 1945, the Japanese military continued to fight tenaciously in defeat after defeat. Few battles were as one-sided as the Battle of the Philippine Sea in June 1944, a Japanese counterattack that the Americans called the Great Marianas Turkey Shoot for the number of planes and vessels that they sank. At Iwo Jima, an eight-square-mile island of volcanic rock upon which the Americans wanted to build an airfield from which to attack Japan, seventeen thousand Japanese soldiers held the island against seventy thousand Marines for over a month. At the cost of nearly their entire force, they inflicted almost thirty thousand casualties before the island was lost in early 1945.

By that time, American heavy bombers were in range of the Japanese homeland. Bombers hit Japan’s industrial facilities but suffered high casualties. To spare bomber crews from dangerous daylight raids and to achieve maximum effect against Japanese morale, American bombers began night raids, dropping incendiary weapons that created massive firestorms consuming the wood-and-paper houses of the residential neighborhoods. Over sixty Japanese cities were fire-bombed; one hundred thousand civilians in Tokyo died in a single attack in March 1945.

In June 1945, after eighty days of fighting and tens of thousands of casualties, the Americans captured the island of Okinawa. The homeland of Japan was open before them. Okinawa was a viable base from which to launch a full invasion of the Japanese homeland and end the war. Estimates varied, but given the tenacity of Japanese soldiers fighting on islands far from their home, some officials expected that an invasion of the Japanese mainland could cost half a million American casualties and kill millions of Japanese civilians.

Historians in the past debated the many motivations that drove the Americans to use atomic weapons against Japan, and many American officials criticized the decision at the time. Government leaders and military officials cited the casualty estimates of an invasion to justify their use. Early in the war, fearing that German scientists might develop an atomic bomb, the German Hungarian American physicist Leó Szilárd had written a letter to Franklin Roosevelt, which Albert Einstein signed, warning of a nuclear-armed Hitler. After some debate, other American physicists acknowledged the possibility. The U.S. government responded in 1942 with the Manhattan Project, a hugely expensive, ambitious program to create a single weapon capable of leveling an entire city. Three years later, the Americans successfully exploded the world’s first nuclear device, Trinity, in New Mexico in July 1945 while Allied leaders were meeting in Potsdam. Physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer, the director of the Los Alamos Laboratory where the bomb was designed, later recalled that the event reminded him of a line from Hindu scripture: “Now I am become death, the destroyer of worlds.”

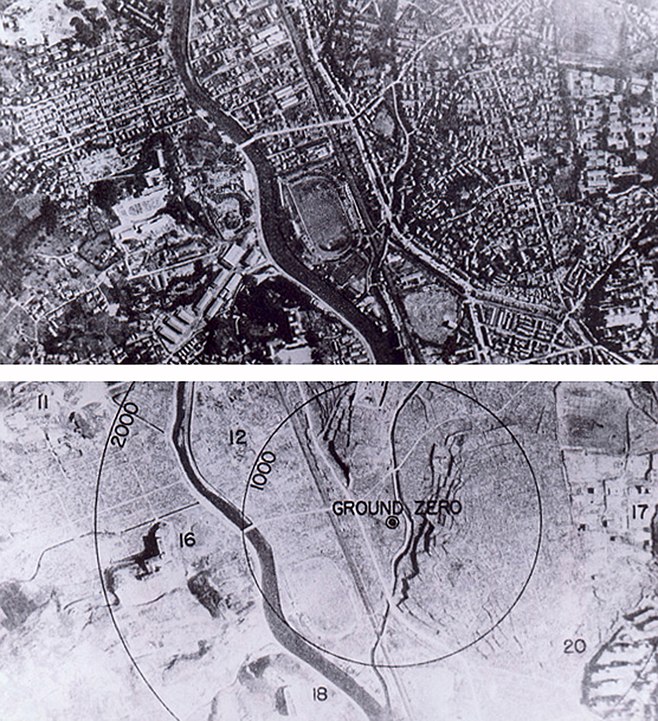

Two more bombs, Little Boy and Fat Man, were quickly built and detonated over two Japanese cities in August. The Hiroshima bomb was dropped at 8:15 on the morning of August 6. Over one hundred thousand civilians were killed. On August 9, the second bomb, Fat Man, was scheduled to be dropped on the castle town of Kokura. But the town was obscured by clouds, so the mission proceeded to the secondary target, Nagasaki, an important port city on the southern island, Kyushu, with a population of about a quarter-million people. The Fat Man bomb detonated over the Mitsubishi munitions factory and the city arsenal. About eighty thousand civilians were killed.

In addition to the American atom bomb attacks, on August 9, Soviet forces invaded Manchuria and overthrew the Japanese puppet state of Manchukuo. On August 10, Japanese cabinet ministers agreed to the Allied terms for surrender. Emperor Hirohito endorsed their decision on August 15 and announced the surrender of Japan. On September 2, aboard the battleship USS Missouri, delegates from the Japanese government formally signed their surrender. World War II was finally over.

Questions for Discussion

- How was the Pacific war different from the European war?

- Was the U.S. justified in dropping atomic bombs on Japan?

U.S. Industry and the “Home Front”

Economies win wars as much as militaries. The war effort converted American factories to wartime production, restored America’s economy to full employment, armed the Allies and American forces, pulled America out of the Great Depression, and ushered in an era of unparalleled economic prosperity. Roosevelt’s New Deal had ameliorated the worst of the Depression, but the economy was still limping its way forward. When Europe fell into war, Americans were glad to sell the Allies arms and supplies. And then Pearl Harbor changed everything. The United States drafted the economy into war service. The “sleeping giant” mobilized its unrivaled economic capacity to wage worldwide war. Government agencies such as the War Production Board and the Office of War Mobilization and Reconversion managed production for the war effort, and economic output exploded. An economy that had been unable to provide work for a quarter of the workforce less than a decade earlier now struggled to fill vacant positions.

Although Franklin Roosevelt had already embraced the ideas of economist John Maynard Keynes on using deficit spending to jump-start the economy, the war wiped away any resistance among conservatives. Government spending during the four years of war doubled all federal spending in all of American history up to that point. The federal budget deficit soared, but just as Keynes had predicted, the government’s massive intervention annihilated unemployment and propelled growth. The economy that came out of the war looked nothing like the one that had begun it.

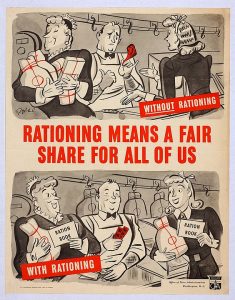

Military production came at the expense of the civilian consumer economy. Appliance and automobile manufacturers converted their plants to produce weapons and vehicles. Consumer choice was sacrificed to patriotic duty. Every American received rationing cards, and goods such as gasoline, coffee, meat, cheese, butter, processed food, firewood, and sugar could not be purchased without them. New house building was shut down, and cities became overcrowded. But the wartime economy boomed. The Roosevelt administration urged citizens to save their earnings or buy war bonds to prevent inflation. Bond drives headlined by Hollywood celebrities were hugely successful. They not only funded much of the war effort; they helped tame inflation as well. So too did high tax rates. The federal government raised income taxes and boosted the top marginal tax rate to 94 percent.

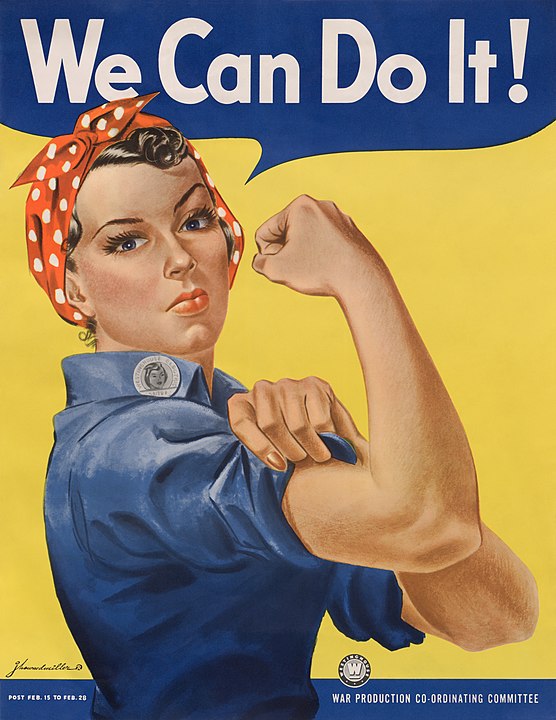

President Roosevelt and his administration encouraged all able-bodied American men and women to help the war effort. He considered the role of women in the war critical for American victory, and the public expected women to free men for active military service. While most women opted to remain at home or volunteer with charitable organizations, many went to work or put on a military uniform. World War II brought unprecedented labor opportunities for American women. Industrial labor, normally dominated by men, shifted to women for the duration of wartime mobilization. Women got jobs in new munitions factories. The image of Rosie the Riveter inscribed with the phrase “We Can Do It!” encouraged female factory labor during the war. And over a million administrative jobs at the local, state, and national levels were transferred from men to women for the duration of the war, often permanently.

For women who chose not to work in factories or government service, many volunteer opportunities presented themselves. The American Red Cross, the largest charitable organization in the nation, encouraged women to volunteer with local city chapters. Millions of women organized community social events for families, packed and shipped almost half a million tons of medical supplies, and prepared twenty-seven million care packages for American and other Allied prisoners of war. The American Red Cross required all female volunteers to certify as nurse’s aides, providing an extra benefit and work opportunity for hospital staffs that suffered severe personnel losses.

Military service was another option for women who wanted to join the war effort. Over 350,000 women served in several all-female units of the military branches. The Army and Navy Nurse Corps Reserves, the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps, the Navy’s Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service, the Coast Guard’s SPARs (named for the Coast Guard motto, Semper Paratus, “Always Ready”), and Marine Corps units gave women the opportunity to serve as either commissioned officers or enlisted members at military bases at home and abroad. The Nurse Corps Reserves commissioned 105,000 army and navy nurses recruited by the American Red Cross. Military nurses worked at base hospitals, mobile medical units, and onboard hospital ships.

However, despite all the wartime and postwar celebration of Rosie the Riveter, when the war ended, men returned home and most women lost their jobs. Many former military women faced difficulty obtaining veteran’s benefits during their transition to civilian life. The nation that called for assistance to millions of women during the four-year crisis seemed unprepared to accommodate their postwar needs and demands. But many women who had answered the call refused to step back into the shadows and pushed forward, igniting a struggle that eventually became the Women’s Movement.

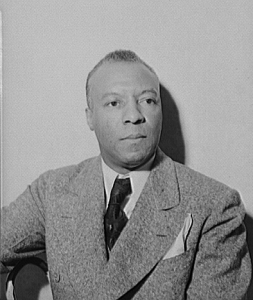

In early 1941, months before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, A. Philip Randolph, president of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, the largest black trade union in the nation, had made headlines by threatening President Roosevelt with a march on Washington, D.C. In this “crisis of democracy,” Randolph said, defense industries refused to hire African Americans and the armed forces remained segregated. In exchange for Randolph calling off the march, Roosevelt issued Executive Order 8802, banning racial and religious discrimination in defense industries and establishing the Fair Employment Practice Committee to monitor defense industry hiring practices. While the armed forces remained segregated throughout the war, the order showed that the federal government could stand against discrimination. The black workforce in defense industries rose from 3 percent in 1942 to 9 percent in 1945.

More than one million African Americans fought in the war. Most blacks served in segregated, noncombat units led by white officers. Some gains were made, however. The number of black officers increased from five in 1940 to over seven thousand in 1945. And all-black fighter and bomber squadrons, known as the Tuskegee Airmen, completed more than 1,500 missions and earned several hundred merits and medals. Black pilots of the 332nd Fighter Group painted the tails of their P-47 Thunderbolts red, and many bomber crews specifically requested the “Red Tail Angels” as escorts. Near the end of the war, the army and navy began integrating some of their units and facilities before the U.S. government finally ordered the full integration of its armed forces in 1948.

While some black Americans served in the armed forces, others on the home front became riveters and welders, rationed food and gasoline, and bought victory bonds. Many black Americans saw the war as an opportunity not only to serve their country but to improve it. The Pittsburgh Courier, a leading black newspaper, spearheaded the “Double V” campaign. It called on African Americans to fight and win two wars: the war against Nazism and fascism abroad and the war against racial inequality at home. To achieve double victory and “real democracy,” the Courier encouraged its readers to enlist in the armed forces or volunteer on the home front and fight against racial segregation and discrimination. During the war, membership in the NAACP jumped tenfold, from fifty thousand to five hundred thousand. The Congress of Racial Equality, formed in 1942, proposed nonviolent direct action to achieve desegregation. Between 1940 and 1950, 1.5 million southern blacks also demonstrated their opposition to racism and violence by migrating out of the Jim Crow South to the North. But transitions were not easy. Racial tensions erupted in 1943 in a series of riots in cities such as Mobile, Beaumont, and Harlem. The bloodiest race riot occurred in Detroit and resulted in the death of twenty-five blacks and nine whites. Still, the war ignited in African Americans an urgency for equality that they would carry with them into the subsequent years.

Questions for Discussion

- How were the experiences of women and African Americans during the war similar?

- How were they different?

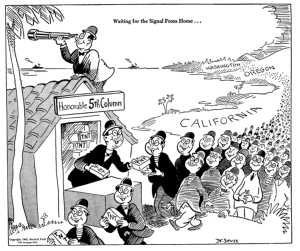

Many Americans had to navigate American prejudice, and America’s entry into the war left foreign nationals from the enemy nations in a precarious position. The Federal Bureau of Investigation targeted many on suspicions of disloyalty for detainment, hearings, and internment under the Alien Enemy Act. Those sentenced to internment were sent to government camps surrounded by barbed wire and armed guards. Early internments were based on determinations of probable cause. Then, on February 19, 1942, President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, authorizing the removal of any persons from “exclusion zones,” which ultimately covered nearly a third of the country, at the discretion of military commanders.

Thirty thousand Japanese Americans fought for the United States in World War II, but wartime anti-Japanese sentiment built on long-standing prejudices. Under Roosevelt’s order, both immigrants and American citizens of Japanese descent were rounded up and placed in prison camps under the custody of the War Relocation Authority. They lost their jobs and homes. Over ten thousand German nationals and a smaller number of Italian nationals were interned at various times in the United States during World War II, but American policies disproportionately targeted Japanese-descended populations, and individuals did not receive personalized reviews prior to their internment. This policy of mass exclusion and detention affected over 110,000 Japanese and Japanese-descended individuals. Seventy thousand were American citizens. In a 1982 report, a congressional commission concluded that the causes of Japanese internment had been “race prejudice, war hysteria, and a failure of political leadership.” Although the exclusion orders were found to have been constitutionally permissible based on claims of national security, they were later judged unjust, even by the military and judicial leaders. In 1988, President Reagan signed an act that formally apologized for internment and provided reparations to surviving internees.

But if actions taken during war would be regretted, so would inactions. As the Allies pushed into Germany and Poland, they uncovered the full extent of Hitler’s genocidal policies. The Allies discovered massive camp systems set up for the imprisonment, forced labor, and extermination of all those Untermenschen (literally, “under-people”) deemed racially, ideologically, or biologically “unfit” to live in a Nazi-ruled Europe. As Russian and American troops liberated concentration and death camps, they discovered the Holocaust, the Nazi state’s systematic murder of eleven million civilians, including six million Jews. But, like the Rape of Nanjing, the Holocaust was not a secret from those who chose to face facts. By the end of the war, it had been under way for years. How did America respond?

Initially, American officials had expressed little official concern for Nazi persecutions. As the first signs of trouble became clear in the late 1930s, the State Department and most U.S. embassies did little to aid European Jews. President Roosevelt publicly spoke out against persecution and even withdrew the U.S. ambassador to Germany after Kristallnacht, the pogrom against German Jews in 1938 that had caused even former German Kaiser Wilhelm II to say, “For the first time, I am ashamed to be German.” Roosevelt pushed for the 1938 Evian Conference in France, where international leaders discussed the Jewish refugee problem and worked to expand Jewish immigration quotas. But the conference came to nothing, and the United States turned away countless Jewish refugees who requested asylum in the United States. In 1939, the German ship St. Louis, carrying over nine hundred Jewish refugees, could not find a country that would take them. Passengers were not granted visas under the U.S. quota system. The ship cabled Roosevelt for special permission, but the president said nothing. The St. Louis was forced to return to Europe. Hundreds of its passengers would perish in the Holocaust.

Anti-Semitism still permeated the United States. Even if Roosevelt wanted to do more, he decided the political price for increasing immigration quotas was too high. After Kristallnacht, in 1939, Congress debated a bill to allow twenty thousand German Jewish children into the United States. First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt endorsed the measure, but the president remained publicly silent. The bipartisan bill was introduced by a Democratic senator and a Republican representative and supported by religious and labor groups but was opposed by nationalist organizations. It never came to a vote in the Senate because it was blocked by a North Carolina Democrat whose support Roosevelt needed on military spending bills. The president, anxious to protect the New Deal and his rearmament programs, was unwilling to expend political capital to save foreign children that even leaders of his own party had little interest in protecting.

Questions for Discussion

- How did racism and prejudice affect the U.S. response to the Jewish refugee problem and Japanese internment?

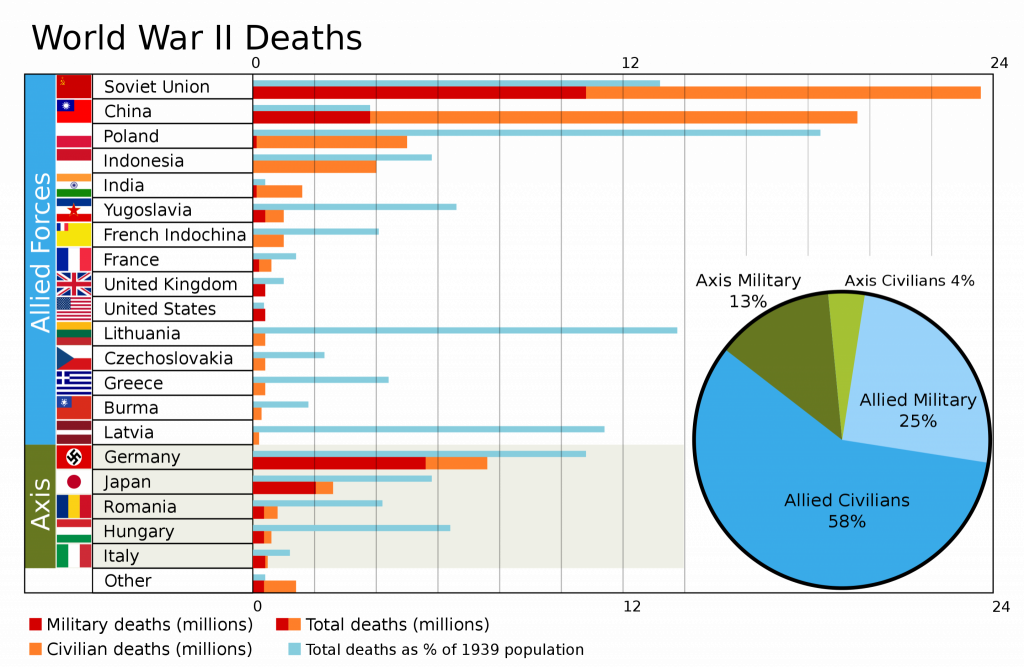

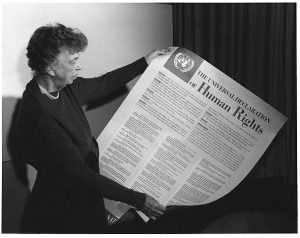

The U.S. was lucky that none of the war was fought on American soil, but 419,400 U.S. servicemen died in the conflict. World War II was the deadliest war in history. Military deaths were over 25 million, including 5 million prisoners of war who died in custody. The war also killed about 55 million civilians, including 28 million who died of war-related disease and famine. The number of wounded has not been accurately documented but was probably similar to or greater than the death toll. More than half those casualties were in Russia and China. The Chinese death toll was at least 20 million. The Soviet Union lost 11,400,000 men in battle, 10 million civilians in war-related activities, and about 7 million through famine caused by the war, for a total of about 28 million. These losses amounted to about 14% of the U.S.S.R.’s 1940 population. Germany lost over 5 million soldiers and up to 3 million civilians. Americans celebrated the end of the war after V-J Day in August 1945. At home and abroad, the United States wanted a postwar order that would guarantee global peace and domestic prosperity. Although the alliance of convenience with Stalin’s Soviet Union would rapidly collapse, Americans nevertheless looked for the means to ensure postwar stability and economic security for returning veterans. The inability of the League of Nations to stop German, Italian, and Japanese aggressions caused many to question whether any global organization could effectively ensure world peace. Skeptics included Franklin Roosevelt, who, as Woodrow Wilson’s undersecretary of the navy, had witnessed the rejection of the League’s ideal of world governance by both the American people and the Senate.

In 1941, Roosevelt believed postwar security could best be maintained by an informal agreement between what he termed the Four Policemen: the United States, Britain, the Soviet Union, and China. But others, including Roosevelt’s secretary of state Cordell Hull and British prime minister Winston Churchill, convinced the president to push for a new global organization. As the war ran its course, both Roosevelt and the American public came around to the idea of the United Nations. Pollster George Gallup noted a “profound change” in American attitudes. In 1937, only a third of Americans polled supported the idea of an international organization. But as war broke out in Europe, half of Americans did. America’s entry into the war bolstered support, and by 1945, 81 percent of Americans favored the idea.

And Franklin Roosevelt had always supported the ideals enshrined in the United Nations charter. In January 1941, he described Four Freedoms that all of the world’s citizens should enjoy: freedom of speech, freedom of worship, freedom from want, and freedom from fear. Roosevelt signed the Atlantic Charter with Churchill, reinforcing those ideas and adding the right of self-determination and promising some sort of economic and political cooperation. Roosevelt first used the term United Nations to describe the Allied powers, not the subsequent postwar organization. But the name stuck.

At Tehran in 1943, Roosevelt and Churchill convinced Stalin to send a Soviet delegation to a conference in August 1944, where they agreed on the basic structure of the new organization. It would have a Security Council, consisting of the original Four Policemen and France, that would consult on how best to keep the peace and when to deploy the military power of the assembled nations. In a shift from the unarmed diplomacy of the League of Nations, the U.N. would have a military. The plan was a hybrid between Roosevelt’s policemen idea and a global organization of equal representation. There would also be a General Assembly made up of all nations, an International Court of Justice, and a council for economic and social matters. The Soviets expressed concern over how the Security Council would work, but the powers agreed to meet again in San Francisco between April and June 1945 for further negotiations. There, on June 26, 1945, fifty nations signed the U.N. charter.

Questions for Discussion

- Reflect on the death toll. Which nations paid the highest price? How might this affect their post-war attitudes in international negotiations?

- How did the United Nations attempt to be a more useful force for world peace?

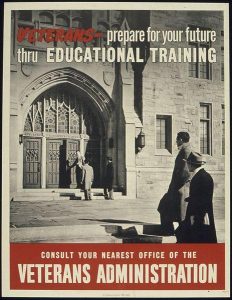

Anticipating victory in World War II, American leaders not only planned the postwar global order; they planned for the returning servicemen. American politicians and business leaders wanted to avoid another economic depression by gradually easing returning veterans back into the civilian economy. The brainchild of William Atherton, the head of the American Legion, the G.I. Bill won support from progressives and conservatives alike. Passed in 1944, the G.I. Bill was a multibillion-dollar entitlement program that rewarded honorably discharged veterans with a range of important benefits.

Faced with the prospect of over fifteen million members of the armed services (including approximately 350,000 women) suddenly returning to civilian life, the G.I. Bill offered a variety of incentives to slow their return to the civilian workforce as well as reward their service with public benefits. The legislation offered a year’s worth of unemployment income for veterans unable to secure work. About half of American veterans (eight million) received a total of $4 billion in unemployment benefits over the life of the bill. The bill also made a college education a reality for many. The Veterans Administration paid educational expenses including tuition, fees, supplies, and even stipends for living expenses, sparking a boom in higher education. Enrollments at accredited colleges, universities, technical, and professional schools spiked from 1.5 million in 1940 to 3.6 million in 1960. The VA disbursed over $14 billion in educational aid in just over a decade.

Furthermore, the G.I. Bill encouraged home ownership. Roughly 40 percent of Americans owned homes in 1945, but that figure climbed to 60 percent a decade after the close of the war. Because the bill did away with down payment requirements, veterans could obtain home loans for as little as $1 down. Close to four million veterans purchased homes through the G.I. Bill, sparking a construction bonanza that propelled postwar growth. In addition, the VA helped nearly two hundred thousand veterans buy farms and offered thousands more guaranteed financing for small businesses. The effects of the G.I. Bill were significant and long-lasting. It helped sustain the great postwar economic boom and established the hallmarks of American middle-class life.

Media Attributions

- Marines_with_LVT(A)-5_in_Iwo_Jima_1945 © Fifth Marine Division photographer is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Selassie_on_Time_Magazine_cover_1930 © Time Magazine is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Soviet_armor_in_the_spanish_civil_war © Textidor is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- Francisco_Franco_1930 © Unknown is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- PicassoGuernica © Picasso is licensed under Fair Use according to Wikimedia

- Bundesarchiv Bild 146-1976-063-32, Bad Godesberg, Münchener Abkommen, Vorbereitung © Bundesarchiv, Bild is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Bundesarchiv Bild 146-1985-083-10, Anschluss Österreich, Wien © Bundesarchiv is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Bundesarchiv_Bild_183-H27337,_Moskau,_Stalin_und_Ribbentrop_im_Kreml © Bundesarchiv is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Manchukuo_map_1939.svg © Emok is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Chinese_to_be_beheaded_in_Nanking_Massacre © H.J.Timperley is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Contest_To_Cut_Down_100_People © Shinju Sato is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Washington, D.C. Madame Chiang Kai-Shek and Mrs. Roosevelt © Roberts is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Bundesarchiv Bild 101l-218-0504-36, Russland-Süd, Panzer III, Schützenpanzer, 23.Pz.Div. (cropped) © Bundesarchiv is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- A Finnish Maxim M-32 machine gun nest during the Winter War © Uknown is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Bundesarchiv_Bild_183-H25217,_Henry_Philippe_Pet ain_und_Adolf_Hitler © Bundesarchiv is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license