Chapter 10: Agriculture and Food

Georgeta Connor and Neusa Hidalgo Monroy Wohlgemuth

STUDENT LEARNING OUTCOMES

By the end of this section, the student will be able to:

- Understand: the origin and evolution of agriculture across the globe

- Explain: the environment-agriculture relationship, market forces, institutions, agricultural industrialization, and biorevolution versus sustainable agriculture

- Describe: agricultural regions, comparing and contrasting subsistence and commercial agriculture

- Connect: the factors of global changes in food production and consumption

CHAPTER OUTLINE

- 10.1 Introduction

- 10.2 Agricultural Practices

- 10.3 Global Changes in Food Production and Consumption

- 10.4 Summary

- 10.5 Key Terms Defined

- 10.6 Works Consulted and Further Reading

10.1 INTRODUCTION

Before the invention of agriculture, people obtained food from hunting wild animals, fishing, and gathering fruits, nuts, and roots. Having to travel in small groups to obtain food, people led a nomadic existence. This remained the only mode of subsistence until the end of the Mesolithic period, some 12,000-10,000 years ago. Then, agriculture gradually replaced the hunting and gathering system, constituting the spread of the Neolithic revolution. Even today, some isolated groups survive as they did before agriculture developed. They can be found in some remote areas such as in Amazonia, Congo, Namibia, Botswana, Tanzania, New Guinea, and the Arctic latitude, where hunting dominates life (Figures 10.1, 10.2, and 10.3).

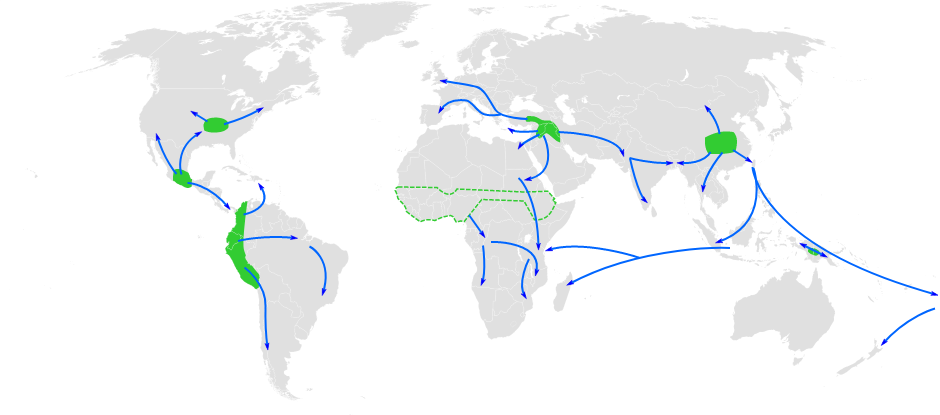

The term agriculture refers to the cultivation of crops and the raising of livestock for both sustenance and economic gain. The origin of agriculture goes back to prehistoric times, starting when humans domesticated plants and animals. The domestication of plants and animals as the origin of agriculture was a pivotal transition in human history, which occurred several times independently. Agriculture originated and spread in different regions (hearths) of the world, including the Middle East, Southwest Asia, Mesoamerica and the Andes, Northeastern India, North China, and East Africa, beginning as early as 12,000–10,000 years ago. People became sedentary, living in their villages, where new types of social, cultural, political, and economic relationships were created. This period of momentous innovations is known as the First Agricultural Revolution.

Take a look below (Figure 10.4) for the locations where major plants and animals were first domesticated. Pull up a reference map on the internet if you don’t know the locations of the green hearths.

10.2 AGRICULTURAL PRACTICES

Agriculture is a science, a business, and an art (Figures 10.5a and 10.5b). Spatially, agriculture is the world’s most widely distributed industry. It occupies more area than all other industries combined, changing the surface of the Earth more than any other. Farming, with its multiple methods, has significantly transformed the landscape (small or large fields, terraces, polders, livestock grazing), being an important reflection of the two-way relationship between people and their environments. The world’s agricultural societies today are very diverse and complex, with agricultural practices ranging from the most rudimentary, such as using the ox-pulled plow, to the most complex, such as using machines, tractors, satellite navigation, and genetic engineering methods. Customarily, scholars divide agricultural societies into categories such as subsistence, intermediate, and developed, words that express the same ideas as primitive, traditional, and modern, respectively. For simplification, farming practices described in this chapter are classified into two categories, subsistence and commercial, with fundamental differences between their practice in developed and developing countries.

10.2.1 Subsistence Agriculture

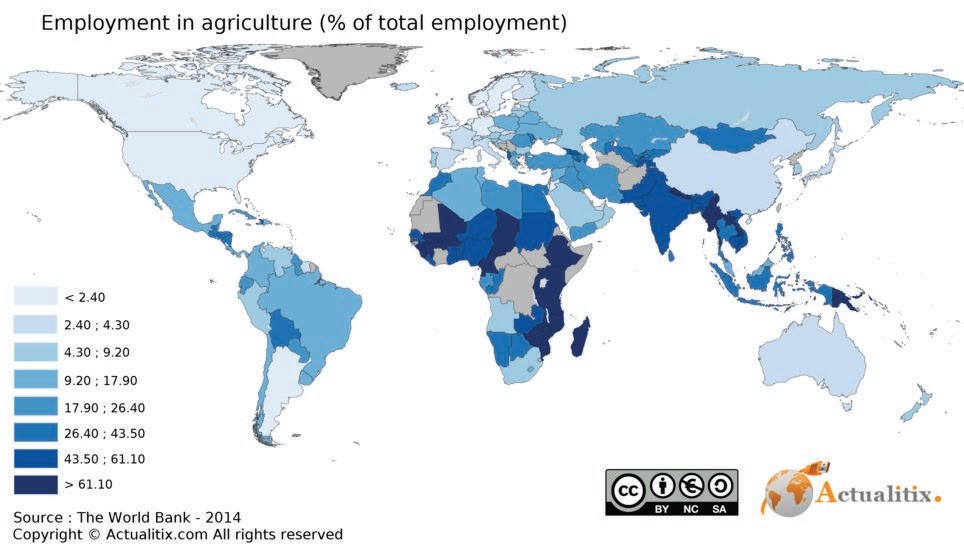

Subsistence agriculture replaced hunting and gathering in many parts of the globe. The term subsistence, when it relates to farming, refers to growing food only to sustain the farmers themselves and their families, consuming most of what they produce, without entering into the cash economy of the country. The farm size is small, 2-5 acres (1-2 hectares), but the agriculture is less mechanized; therefore, the percentage of workers engaged directly in farming is very high, reaching 50 percent or more in some developing countries (Figure 10.6). Climate regions play an important role in determining agricultural regions. Farming activities range from shifting cultivation to pastoralism, both extensive forms that still prevail over large regions, to intensive subsistence.

Figure 10.6 Employment in Agriculture, 2014; Author | Actualitix; Source | Actualitix.com; License | CC BY NC SA 4.0.

10.2.1.1 Shifting Cultivation

Shifting cultivation, also known as slash-and-burn agriculture, is a form of subsistence agriculture that involves a kind of natural rotation system. Shifting cultivation is a way of life for 150-200 million people, globally distributed in tropical areas, especially in the rain forests of South America, Central and West Africa, and Southeast Asia. The practices involve removing dense vegetation, burning the debris, clearing the area, known as swidden, and preparing it for cultivation (Figure 10.7). Shifting cultivation can successfully support only low population densities, and as a result of the rapid depletion of soil fertility, the fields are actively cultivated usually for three years. As a result, the infertile land has to be abandoned, and another site has to be identified, starting again the process of clearing and planting. The slash-and-burn technique thus requires extensive acreage for new lots, as well as a great deal of human labor, involving at the same time a frequent gender division of labor. The kinds of crops grown can be different from region to region, dominated by tubers, sweet potatoes especially, and grains such as rice and corn. The practice of mixing different seeds in the same swidden in the warm and humid tropics is favorable for harvesting two or even three times per year. Yet, the slash-and-burn practice has some negative impacts on the environment, being seen as ecologically destructive, especially for areas with vulnerable and endangered species.

10.2.1.2 Pastoralism

Involving the breeding and herding of animals, pastoralism is another extensive form of subsistence agriculture. It is adapted to cold and/or dry climates of savannas (grasslands), deserts, steppes, high plateaus, and Arctic zones where planting crops is impracticable. Specifically, the practice is characteristic in Africa (north, central [Sahel], and south), the Middle East, central and southwest Asia, the Mediterranean basin, and Scandinavia. The species of animals vary with the region of the world including, especially, sheep, goats, cattle, reindeer, and camels. Pastoralism is a successful strategy to support a population on less productive land and adapt well to the environment. Three categories of pastoralism can be individualized: sedentary, nomadic, and transhumance.

Sedentary pastoralism refers to those farmers who live in their villages and their herd animals in nearby pastures. Several men usually are hired by the villagers to take care of their animals. Equally important is the practice in which the hired men gather the animals (cattle especially) in the morning, feed them during the day in the nearby pasture, and then return them to the village early in the evening. This is the typical pattern for many traditional European pastoralists.

Nomadic pastoralism is a traditional form of subsistence agriculture in which the pastoralists travel with their herds over long distances and with no fixed pattern. This is a continuous movement of groups of herds and people such as the Bedouins of Saudi Arabia, the Bakhtiaris of Iran, the Berbers of North Africa, the Maasai of East Africa, the Zulus of South Africa, the Mongols of Central Asia, and other groups. The settlement landscape of pastoral nomads reflects their need for mobility and flexibility. Usually, they live in a type of tent (known as a yurt in Central Asia) and move their herds to any available pasture (Figure 10.8). Although there are approximately 10-15 million nomadic pastoralists in the world, they occupy about 20 percent of Earth’s land area. Today, their life is in decline, the victim of more constricting political borders, competing land uses, selective overgrazing, and government resettlement programs.

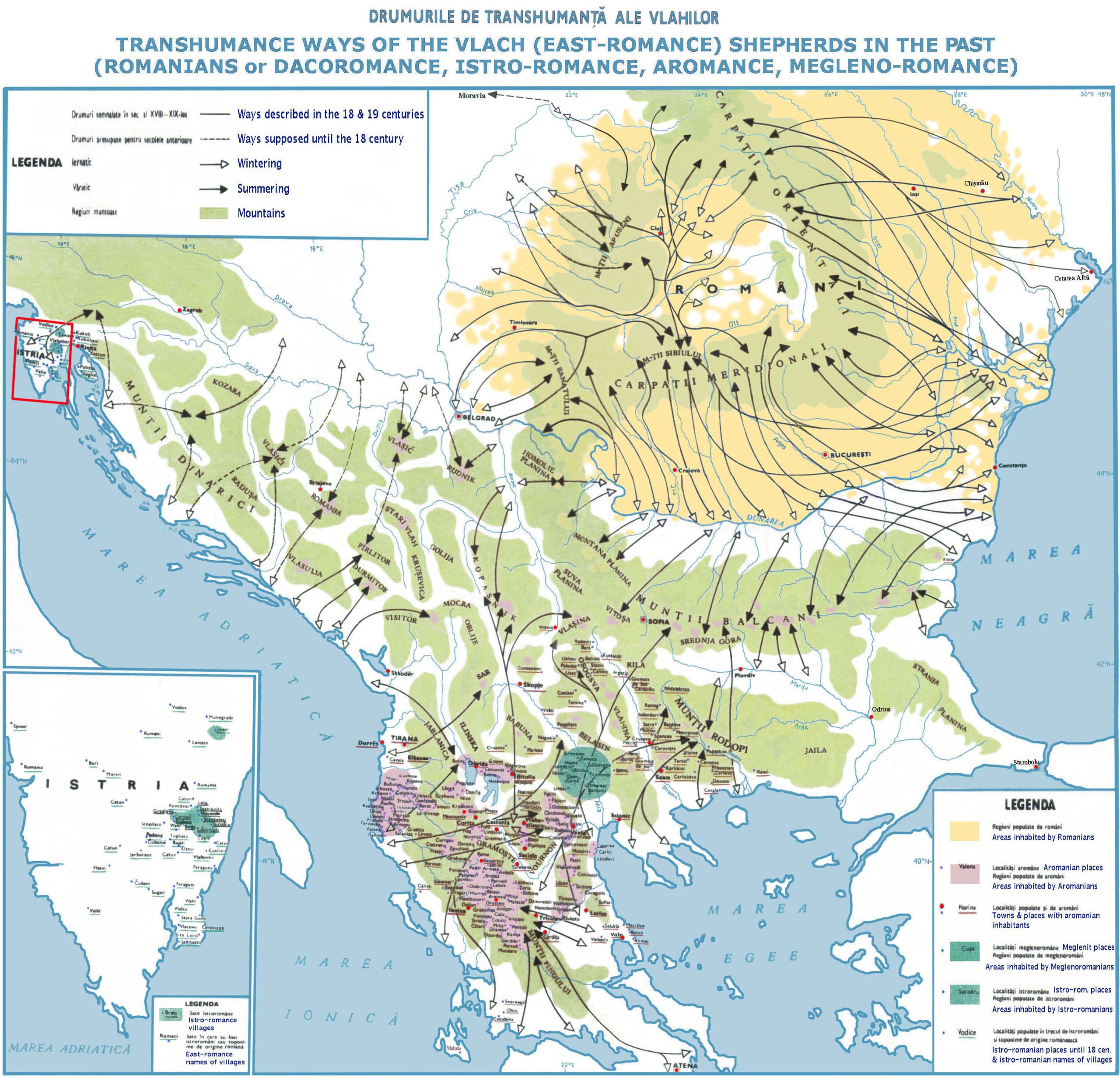

Transhumance is a seasonal vertical movement by herding the livestock (cows, sheep, goats, and horses) to cooler, greener high-country pastures in the summer and then returning them to lowland settings for fall and winter grazing.

Herders have a permanent home, typically in the valleys. Generally, the herds travel with a certain number of people necessary to tend them, while the main population stays at the base. This is a traditional practice in the Mediterranean and the Black Sea basins such as southern European countries, the Carpathian Mountains, and the Caucasus countries (Figures 10.9 and 10.10). In addition, near highland zones such as the Atlas Mountains (northwest Africa) and the Anatolian Plateau (Turkey), as well as in Sub-Saharan Africa, the Middle East countries, and Central Asia, the pastoralists have to practice another type of transhumance, such as the movement of animals between wet-season and dry-season pasture.

10.2.1.3 Intensive Subsistence Agriculture

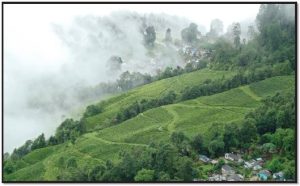

Intensive subsistence agriculture, characteristic of densely populated regions especially in southern, southeastern, and eastern Asia, involves the effective and efficient use of small parcels of land to maximize crop yield per acre. The practice requires intensive human labor, with most of the work being done by hand and/or with animals. The landscape of intensive subsistence agriculture is significantly transformed, including hillside terraces and raised fields, adding irrigation systems and fertilizers (Figures 10.11 and 10.12). As a result, intensive subsistence agriculture can support large rural populations. Rice is the dominant crop in the humid areas of southern, southeastern, and eastern Asia. In the drier areas, other crops are cultivated such as grains (wheat, corn, barley, millet, sorghum, and oats), as well as peanuts, soybeans, tubers, and vegetables. In both situations, the land is intensively used, and the milder climate of those regions allows double cropping (the fields are planted and harvested two times per year).

In recent decades, as the result of the introduction of higher-yielding grain varieties such as wheat, corn, and rice, known as the Green Revolution, tens of millions of subsistence farmers have been lifted above the survival level. The spread of these new varieties throughout the farmlands of South, Southeast, and East Asia and Mexico greatly improved the supply of food in these areas. Equally important was the use of fertilizers, pesticides, irrigation, and new machines. Today, China and India are self-sufficient in basic foods, while Thailand and Vietnam are two of the top rice exporters in the world. Although hunger and famine persist in some regions of the world, especially in Africa, many people accept that they would be much worse without using these innovations.

10.2.2 Commercial Agriculture

Commercial agriculture, generally practiced in core countries outside the tropics, is developed primarily to generate products for sale to food processing companies. An exception is plantation farming, a form of commercial agriculture which persists in developing countries side by side with subsistence. Unlike the small subsistence farms (1-2 hectares/2-5 acres), the average commercial farm size is over 150 hectares/370 acres (178 ha/193 acres U.S.), and, being mechanized, many of them are family-owned and operated. Mechanization also determines the percentage of the labor force in agriculture, with many developed countries being even below two percent of the total employment, such as Israel, the United Kingdom, Germany, the United States, Canada, Norway, Denmark, and Sweden (Figure 10.6). Moreover, as a result of industrialization and urbanization, many developed countries continue to lose significant areas of agricultural land. North America, for example, had 28.3 percent agricultural land out of the total land area in 1961 and 26 percent in 2014. The European Union decreased its agricultural land from 54.7 percent to 43.8 percent for the same period, during which some countries recorded outstanding decreases, such as Ireland from 81.9 to 64.8 percent, the United Kingdom from 81.8 to 71.2 percent, and Denmark from 74.6 to 62.2 percent, to mention only a few. In addition to the high level of mechanization, to increase their productivity, commercial farmers use scientific advances in research and technology such as the Global Positioning System (autonomous precision seed-planting robot, intelligent systems for animal monitoring, savings in field vegetable-growing through the use of a GPS automatic steering system) and satellite imagery (finding efficient routes for selective harvesting based on remote sensing management).

Climate regions also play an important role in determining agricultural regions. In developed countries, these regions can be individualized into six types of commercial agriculture: mixed crop and livestock, grain farming, dairy farming, livestock ranching, commercial gardening and fruit farming, and Mediterranean agriculture.

10.2.2.1 Mixed Crop and Livestock

Mixed crop and livestock farming extends over much of the eastern United States, central and western Europe, western Russia, Japan, and smaller areas in South America (Brazil and Uruguay) and South Africa. The rich soils, typically involving crop rotation, produce high yields primarily of corn and wheat, adding also soybeans, sugar beets, sunflower, potatoes, fruit orchards, and forage crops for livestock. In practice, there is a wide variation in mixed systems. At a higher level, a region can consist of individual specialized farms (corn, for example) and service systems that together act as a mixed system. Other forms of mixed farming include the cultivation of different crops on the same field or several varieties of the same crop with different life cycles, using space more efficiently, and spreading risks more uniformly. The same farm may grow cereal crops or orchards, for example, and keep cattle, sheep, pigs, or poultry (Figure 10.13).

10.2.2.2 Grain Farming

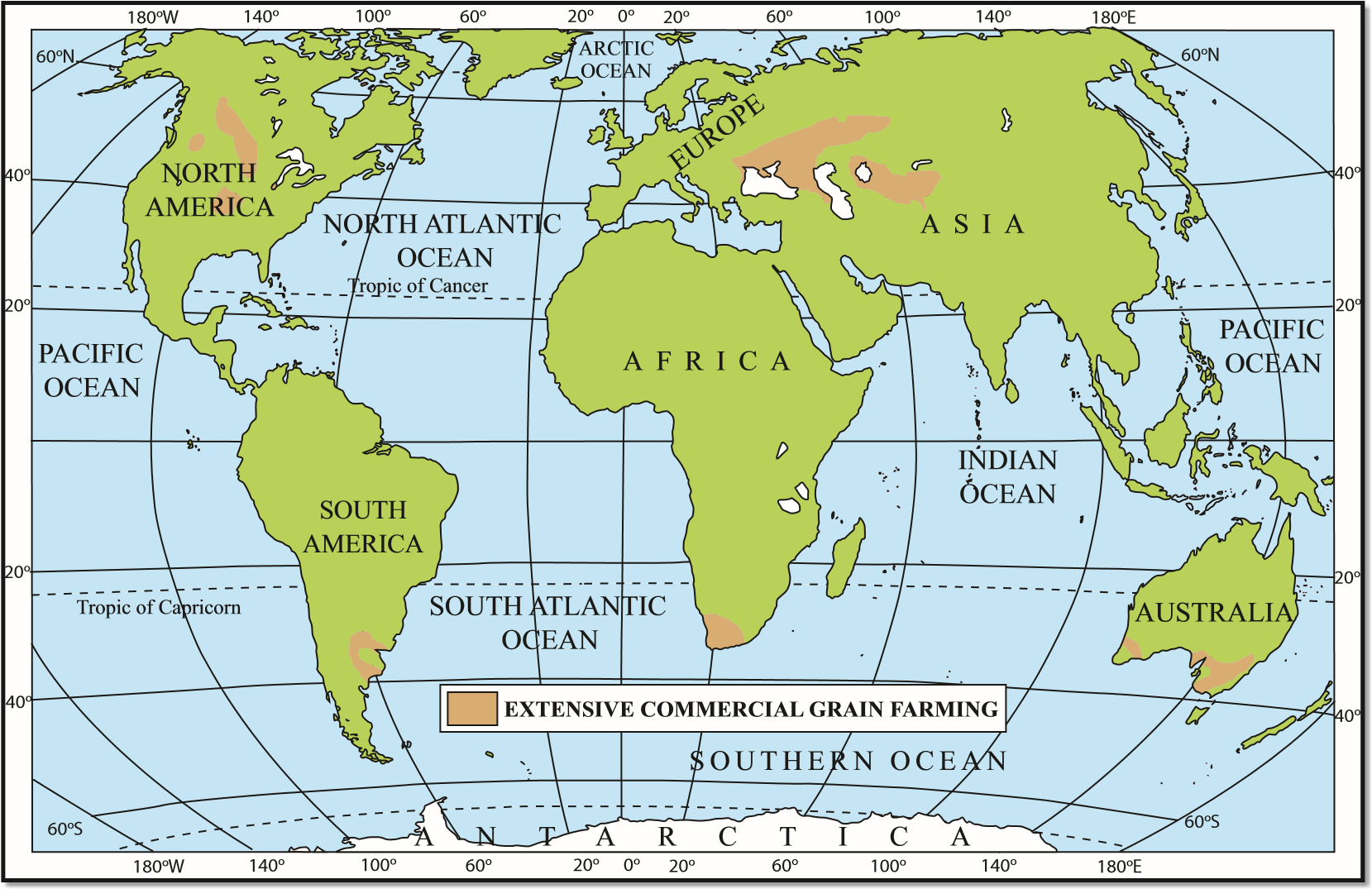

Commercial grain farming is an extensive and mechanized form of agriculture. This is a development in the continental lands of the mid-latitudes (mostly between 30° and 55° North and South latitudes), in regions that are too dry for mixed crop and livestock farming. The major world regions of commercial grain farming are located in Eurasia (from Kyiv, in Ukraine, along southern Russia, to Omsk in western Siberia and Kazakhstan) and North America (the Great Plains). In the southern hemisphere, Argentina, in South America, has a large region of commercial grain farming, and Australia has two such areas, one in the southwest and another in the southeast. Commercial grain farming is highly specialized, and generally, one single crop is grown. The most important crop grown is wheat (winter and spring), used to make flour (Figure 10.14). The wheat farms are very large, ranging from 240 to 16,000 hectares (593-40000 acres). The average size of a farm in the U.S. is about 1000 acres (405 hectares). In these areas land is cheap, making it possible for a farmer to own very large holdings.

10.2.2.3 Dairy Farming

Dairy farming is a branch of agriculture designed for the long-term production of milk, processed either on a farm or at a dairy plant, for sale. It is practiced near large urban areas in both developed and developing countries. The location of this type of farm is dictated by the highly perishable milk. The ring surrounding a city where fresh milk is economically viable, and supplied without spoiling, is about a 100-mile radius. In the 1980s and 1990s, robotic milking systems were developed and introduced in some developing countries, principally in the EU (Figure 10.15). There is an important variation in the pattern of dairy production worldwide. Many countries that are large producers consume most of this internally, while others, in particular New Zealand, export a large percentage of their production, some from organic farms (Figure 10.16).

10.2.2.4 Livestock Ranching

Ranching is the commercial grazing of livestock on large tracts of land. It is an efficient way to raise livestock to provide meat, dairy products, and raw materials for fabrics. Contemporary ranching has become part of the meat-processing industry. Primarily, ranching is practiced on semiarid or arid land where the vegetation is too sparse and the soil too poor to support crops and is a vital part of economies and rural development around the world. In Australia, like in the Americas, ranching is a way of life (Figure 10.17). In the United States, near Greeley, Colorado, there is the world’s largest cattle feedlot, with over 120,000 head, a subsidiary of the food giant ConAgra (Figure 10.18). The largest beef-producing company in the world is the Brazilian multinational corporation JBS-Friboi. Argentina and Uruguay are the world’s top per capita consumers of beef. China is the leading producer of pig meat, while the United States leads in the production of chicken and beef.

10.2.2.5 Commercial Gardening and Fruit Farming

A market garden is a relatively small-scale business, growing vegetables, fruits, and flowers (Figure 10.19). The farms are small, from under one acre to a few acres (.5-1.5 hectares). The diversity of crops is sometimes cultivated in greenhouses, distinguishing it from other types of farming. Commercial gardening and fruit farming are quite diverse, requiring more manual labor and gardening techniques. In the United States, commercial gardening and fruit farming are the predominant types of agriculture in the Southeast, the region with a warm and humid climate and a long growing season. In addition to the traditional vegetables and fruits (tomatoes, lettuce, onions, peaches, apples, cherries), a new kind of commercial gardening has developed in the Northeast. This is a non-traditional market garden, growing crops that, although limited, are increasingly demanded by consumers, such as asparagus, mushrooms, peppers, and strawberries. Market gardening has become an alternative business, significantly profitable and sustainable, especially with the recent popularity of organic and local food.

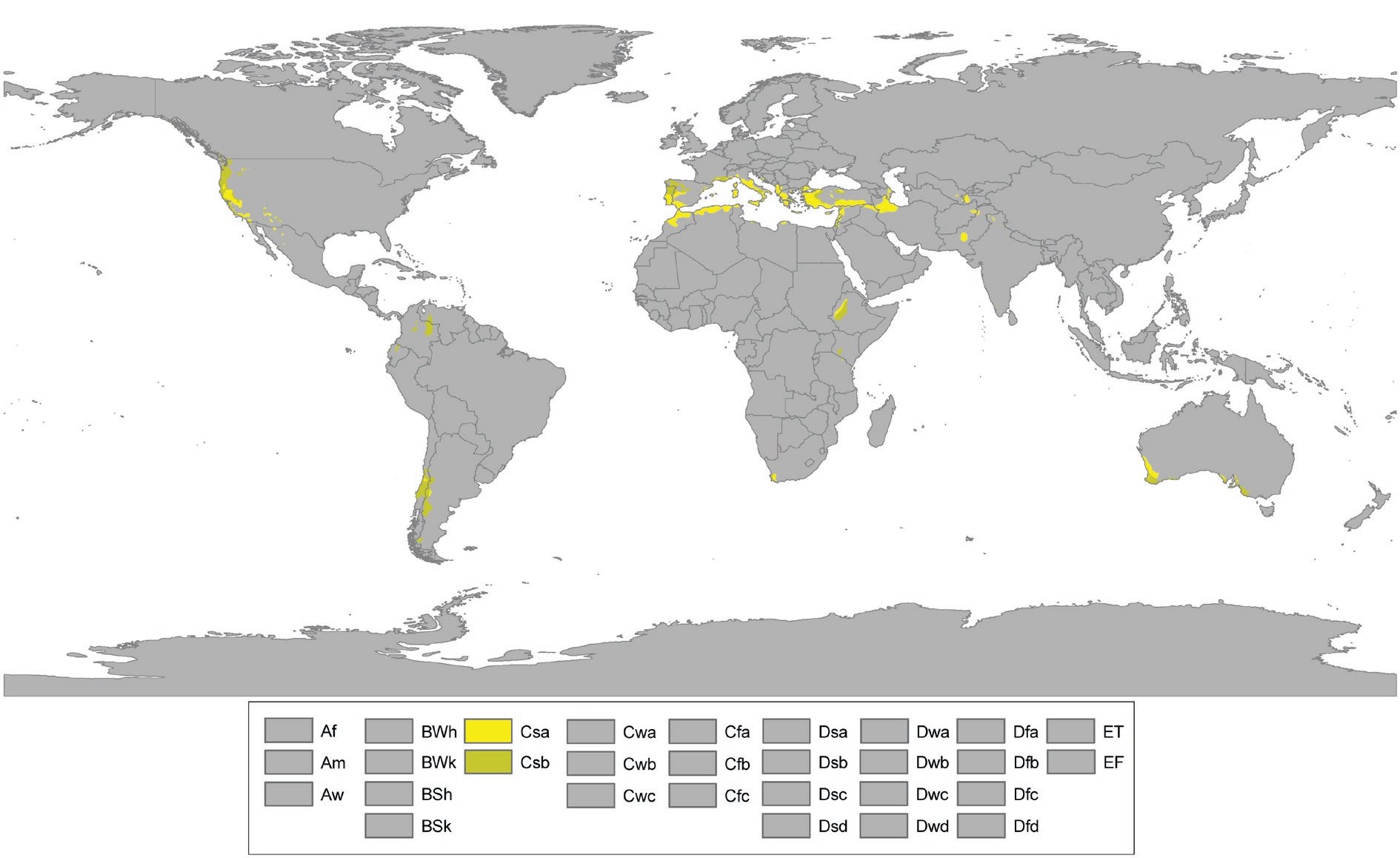

10.2.3 Mediterranean Agriculture

The term “Mediterranean agriculture” applies to the agriculture done in those regions that have a Mediterranean type of climate, hot and dry summers, and moist and mild winters. Five major regions in the world have a Mediterranean type of agriculture, such as the lands that border the Mediterranean Sea (South Europe, North Africa, and the Middle East), California, central Chile, South Africa’s Cape, and in parts of southwestern and southern Australia (Figure 10.20). Farming is intensive, highly specialized, and varied in the kinds of crops raised. The hilly Mediterranean lands, also known as “orchard lands of the world,” are dominated by citrus fruits (oranges, lemons, and grapefruits), olives (primarily for cooking oil), figs, dates, and grapes (primarily for wine), which are mainly for export. These and other commodities flow to distant markets, Mediterranean products tending to be popular and commanding high prices. Yet, the warm and sunny Mediterranean climate also allows a wide range of other food crops, such as cereals (wheat, especially) and vegetables, cultivated especially for domestic consumption.

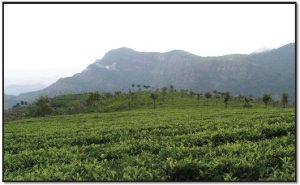

10.2.4 Plantation Farming

Plantations are large landholdings in developing regions designed to produce crops for export. These forms of farming are commonly found in LDCs but are often owned by corporations in MDCs. Plantations also tend to import workers and provide food, water, and shelter necessities for workers to live there year-round. Usually, they specialize in the production of one particular crop for the market laid out to produce coffee, cocoa, bananas, or sugar in South and Central America; cocoa, tea, rice, or rubber in West and East Africa; tea in South Asia; rubber in Southeast Asia; and/or other specialized and luxury crops such as palm oil, peanuts, cotton, and tobacco (Figures 10.21 and 10.22). Plantations are located in the tropical and subtropical regions of Asia, Africa, and Latin America, and although they are located in developing countries, many are owned and operated by European or North American individuals or corporations. Even those taken by governments of the newly independent countries continued to be operated by foreigners to receive income from foreign sources. These plantations survived during decolonization, continuing to serve the rich markets of the world. For more information on plantation farming and its dependence on enslaved populations in the past, explore this article on the The Plantation System.

Unlike coffee, sugar, rice, cotton, and other traditional crops, exported from large plantations, other crops can be required by the international market such as flowers and specific fruits and vegetables. These represent the nontraditional agricultural exports, which have become increasingly important in some countries or regions such as Argentina, Colombia, Chile, Mexico, and Central America, to mention a few. One important reason for sustaining nontraditional exports is that they complement traditional exports, generating foreign exchange and employment. Thus, plantation agriculture, designed to produce crops for export, is critical to the economies of many developing countries.

Louisiana’s plantations were located along the Mississippi River on what is known as “The River Road,” which was used to transport the crops to the ports; they took advantage of the rich alluvial soil from the Mississippi. Before sugar cane, these lands were used to grow indigo, tobacco, cotton, and other crops.

Today Louisiana is among the top ten states in the production of sugar cane, sweet potatoes, rice, cotton, soybeans, and pecans. As for “specialty” commodities, the state ranks number one in the nation for the production of crawfish, shrimp, alligators, and oysters.

10.3 GLOBAL CHANGES IN FOOD PRODUCTION AND CONSUMPTION

10.3.1 Commercial Agriculture and Market Forces

The second agricultural revolution coincided with the Industrial Revolution; it was a revolution that would move agriculture beyond subsistence to generate the kinds of surpluses needed to feed thousands of people working in factories instead of in agricultural fields. Innovations in farming techniques and machinery that occurred in the late 1800s and early 1900s led to better diets, and longer life expectancy, and helped sustain the second agricultural revolution. The railroad helped move agriculture into new regions, such as the United States Great Plains. Geographer John Hudson traced the major role railroads and agriculture played in changing the landscape of that region from open prairie to individual farmsteads. Later, the internal combustible engine made possible the mechanization of machinery and the invention of tractors, combines, and a multitude of large farm equipment. New banking and lending practices helped farmers afford new equipment. In the 1800s, Johann Heinrich von Thünen (1783–1850) experienced the second agricultural revolution firsthand—because of this he developed his model (the Von Thünen Model), which is often described as the first effort to analyze the spatial character of economic activity. This was the birth of commercial agriculture.

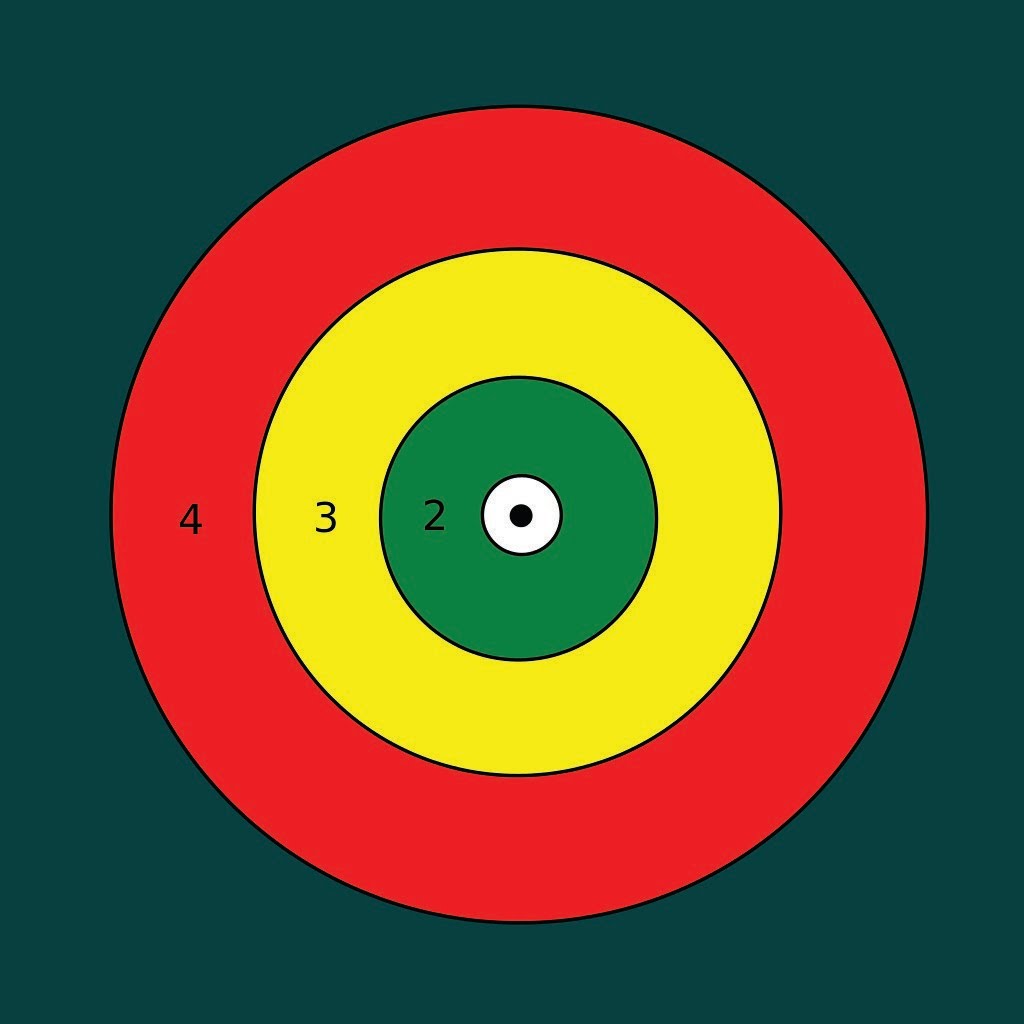

Farming is part of agribusiness as a complex political and economic system that organizes food production from the development of seeds to the retailing and consumption of agricultural products. Although farming is just one stage of the complex economic process, it is incorporated into the world economic system of capitalism (globalized). Most farms are owned by individual families, but in this context, many other aspects of agribusiness are controlled by large corporations. Consequently, this type of farming responds to market forces rather than to feed the farmer. Using Von Thünen’s isolated state model, which generated four concentric rings of agricultural activity, geographers explain that the choice of crops on commercial farms is only worthwhile within certain distances from the city. The effect of distance determines that highly perishable products (milk, fresh fruits, and vegetables) need to be produced near the market, whereas grain farming and livestock ranching can be located on the peripheral rings (Figure 10.23).

The dot represents a city. The white area around it (1) represents dairy and market gardening; 2) (green) the forest for fuel; 3) (yellow) field crops and grains; 4) (red) ranching and livestock; and the outer (dark green) region represents the wilderness where agriculture is not practiced.

New Zealand, for example, is a particular case of a country whose agriculture was thrown into a global free market. More specifically, its agriculture has changed in response to the restructuring of the global food system and, at the same time, is responding to a new global food regime. For New Zealand to remain competitive, farmers have to intensify the production of high-added value or more customized products, also focusing on nontraditional exports such as kiwi, Asian pears, vegetables, flowers, and venison (meat produced on deer farms) (Figure 10.24). The New Zealand agricultural sector is unique in being the only developed country to be totally exposed to international markets since the government subsidies were removed.

10.3.2 Biotechnology and Agriculture

Since the 19th century, manipulation and management of biological organisms have been key to the development of agriculture. In addition to the Green Revolution, agriculture has also undergone a biorevolution, involving agricultural biotechnology (agritech), an area of agricultural science involving the use of scientific tools and genetic engineering techniques to modify living organisms (or part of organisms) of plants and animals with the potential of outstripping the productivity increases of the Green Revolution and, at the same time, reducing agricultural production costs. Within the agricultural biotechnology process, desired traits are exported from a particular species of crop or animal to different species obtaining transgenic crops, which possess desirable characteristics in terms of flavor, the color of flowers, growth rate, size of harvested products, and resistance to diseases and pests (BT corn, for example, can produce its pesticides).

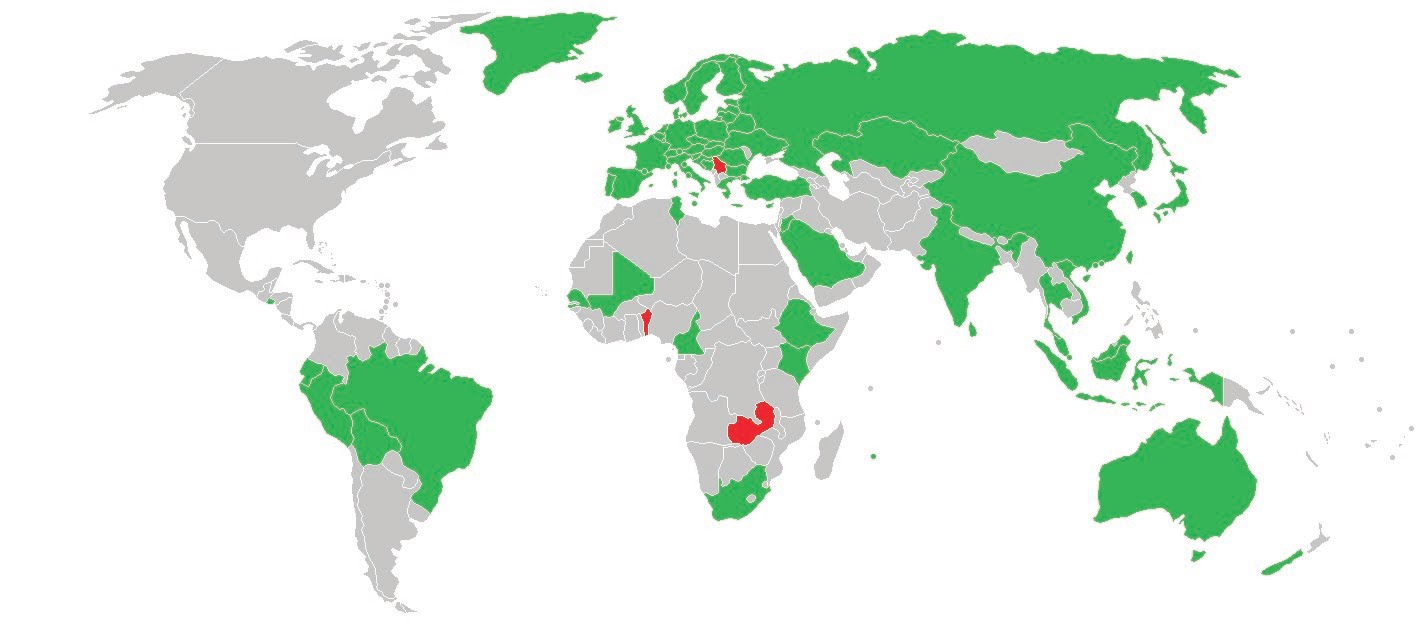

By removing the genetic material from one organism and inserting it into the permanent genetic code of another, the biotech industry has created an astounding number of organisms that are not produced by nature. It has been estimated that upwards of 75 percent of processed foods on supermarket shelves—from soda to soup, crackers to condiments—contain genetically engineered ingredients. So far, little is known about the impacts of genetically modified (GM) foods on human health and the environment. Consequently, it is difficult to sort the benefits from the costs of their increasing incorporation into global food production. The United States is the leader not only in the number of genetically engineered (GE) food crops but also in the largest areas planted with commercialized biotech crops. Many countries in Europe, for example, consider that genetic modification has not been proven safe, the reason for which they require all food to be labeled and refuse to import GM food. Yet, in the United States, genetic modification is permitted, taking into consideration that there is no evidence yet supporting that it is dangerous. Many people instead consider that they have the right to decide what they eat, and consequently, in their opinion, labeling of GM products must be mandatory. Protests against GMO regulatory structures have been very effective in many countries including the United States (Figure 10.25).

Currently, over 60 countries around the world require labeling of genetically modified foods, including 28 nations in the European Union, Japan, Australia, Brazil, Russia, India, South Africa, China, and other countries (Figure 10.26). The debates regarding labeling certainly will continue. Since no one knows whether GM foods are entirely bad or entirely good, regulatory structures are crucial in protecting human health and the environment.

10.3.3 Food and Health

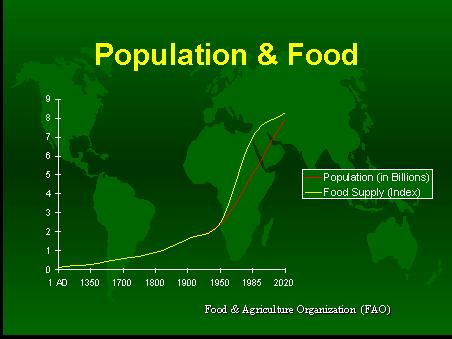

Since the end of World War II, the world’s technically and economically feasible food production potential has significantly expanded. As a result, today, there is more than enough food to feed all the people on Earth (Figure 10.27) Yet, the major issue is the access to food, which is uneven, the reason for which millions of individuals in both the core and the periphery are affected by poverty, preventing them from securing adequate nutrition.

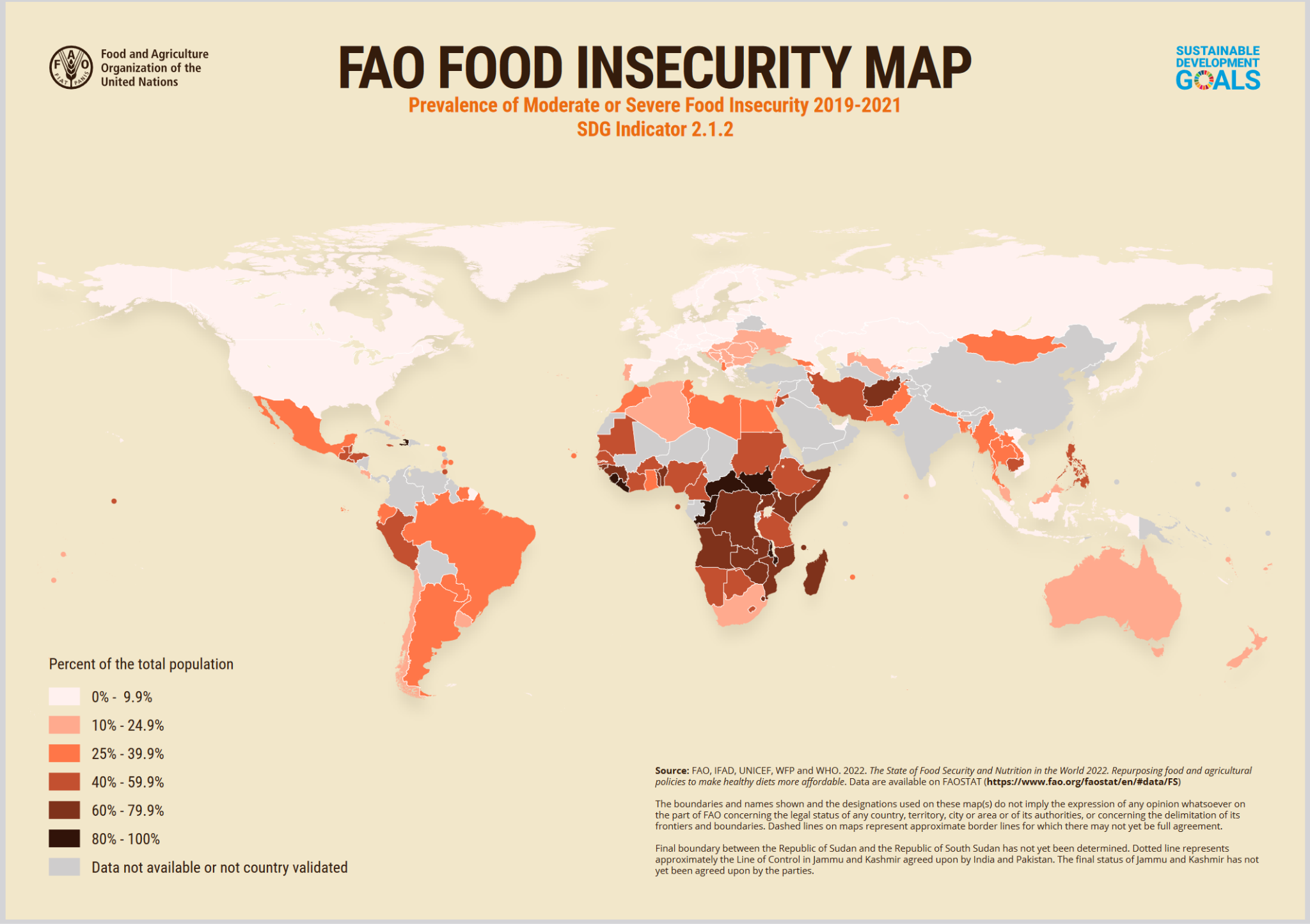

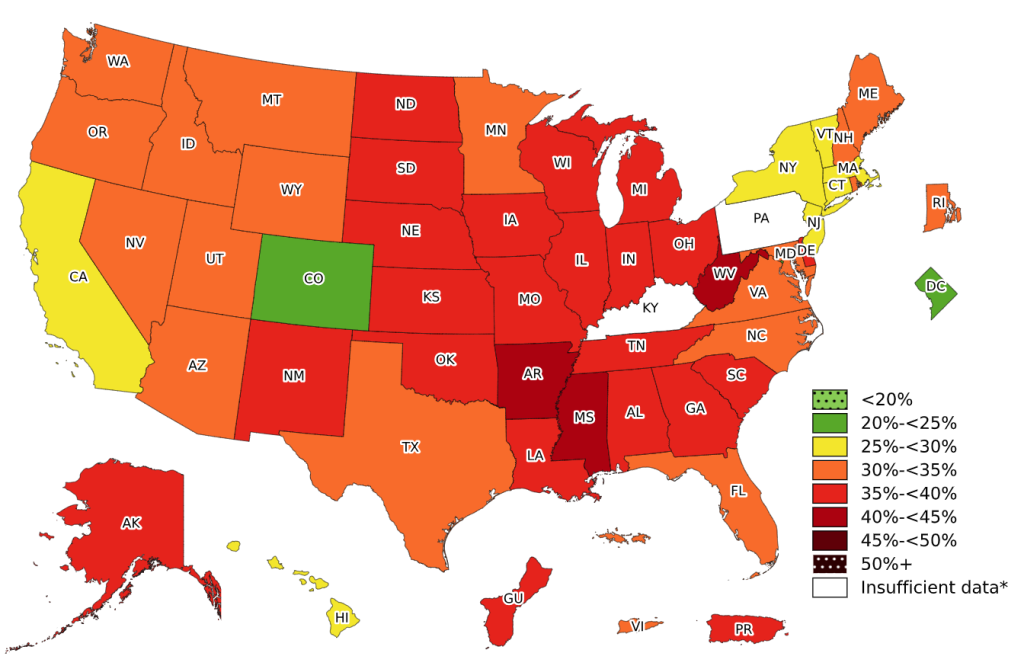

Hunger, chronic (long-term) or acute (short-term), therefore, is one of the most pressing issues facing the world today. Chronic hunger, also known as undernutrition, is an inadequate consumption of the necessary nutrients and/or calories. The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) considers at least 1,800 kcal/day for an individual to consume to maintain a healthy life. The world average consumption is 2,780 kcal/day, but there is a significant difference between developed countries, with an average of 3,470 kcal/day (3,800 kcal/day in the U.S.), and developing countries, recording an average of 2,630 kcal/day (even less in sub-Saharan countries). FAO estimates that currently about 800 million people are undernourished globally, significantly less than in the early 1990s, but the majority continue to be counted in southern Asia and sub-Saharan Africa (Figure 10.28). One form of hunger is famine, an acute starvation caused even by a population’s command over food resources, natural disasters (e.g., drought in Ethiopia in 1984–1985), or wars. In contrast, in North America, the United States especially, where the food is abundant and inspected for quality, overeating is a national problem, the reason for which the general condition of the population is reflected more by obesity (Figure 10.29).

Nutritional vulnerability is conceptualized in terms of the notion of food security. According to FAO, food security exists when all people, at all times, have access to food for an active and healthy life. Related to food security is the concept of food sovereignty, which is the right of people, communities, and countries to define their agricultural policies. One factor connected with food in general and food sovereignty especially is the fact that more cropland is redirected to raising biofuels, fuels derived from biological materials. They not only have a significant and increasing impact on global food systems but also result in the evictions of small farmers and poor communities.

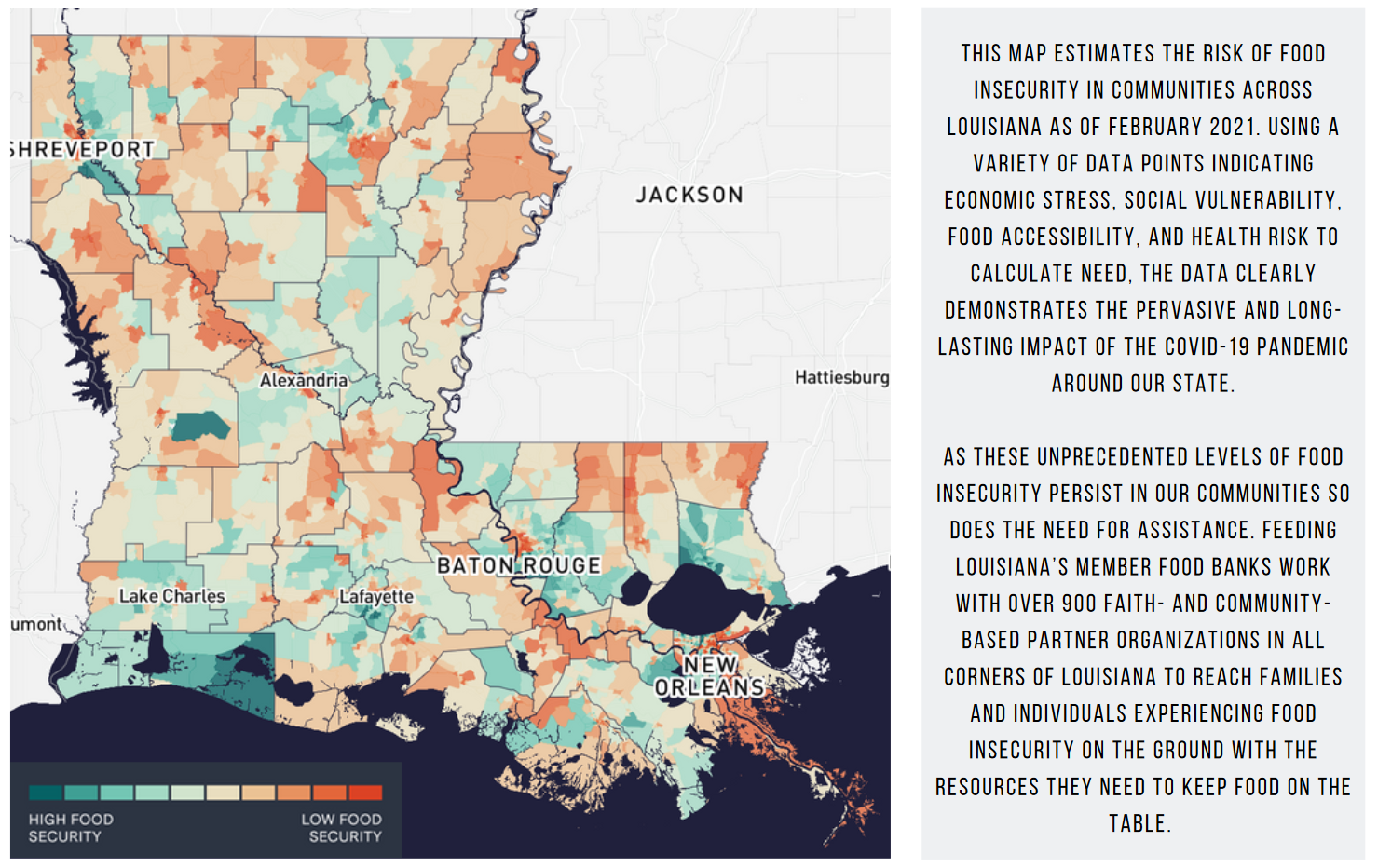

LOUISIANA: According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, 10.4 percent of American households experienced hunger in 2021. These states have the highest percentages of American households who experienced hunger: Mississippi, Arkansas, Louisiana, West Virginia, Oklahoma, Texas, Alabama, South Carolina, Kentucky, and Missouri. See Figure 10.30 to see where in Louisiana to find the parishes with low food security. Access maps and data from the United States Department of Agriculture for the state of Louisiana.

10.3.4 Sustainable Agriculture

Alongside the emergence of a core-oriented food regime especially of fresh fruits and vegetables, a new orientation in agriculture is sustainability. According to the Sustainable Agriculture Initiative (SAI), “sustainable agriculture is the efficient production of safe, high-quality agricultural products, in a way that protects and improves the natural environment, the social and economic conditions of farmers, their employees and local communities, and safeguards the health and welfare of all farmed species” (SAI Platform 20102018). More specifically, sustainability in agriculture is the increased commitment to organic farming, the principles, and practices for sustainable agriculture developed by SAI being articulated around three main pillars: society, economy, and environment.

Although organic food production is not the primary mode of agricultural practice, it has already become a growing force alongside the dominant conventional farming. Yet, unlike conventional farming, which promotes monoculture on large commercial farms and uses chemicals and intensive hormone practices, organic farming, which puts small-scale farmers at the center of food production, does not use genetically modified seeds, synthetic pesticides, herbicides, or fertilizers. Thus, sustainable agricultural practices not only promote diversity and healthy food but also preserve and enhance environmental quality.

10.4 SUMMARY

Agriculture was the key development in the rise of sedentary human civilization, domesticating species of plants and animals and creating food surpluses that nurtured the development of civilization. It began independently in different parts of the globe, both the Old and New World. Throughout history, agriculture played a dynamic role in expanding food supplies, creating employment, and providing a rapidly growing market for industrial products. Although subsistence, self-sufficient agriculture has largely disappeared in Europe and North America, it continues today in large parts of rural Africa and parts of Asia and Latin America. While traditional forms of agricultural practices continue to exist, they are overshadowed by the global industrialization of agriculture, which has accelerated in the last few decades. Yet, commercial agriculture differs significantly from subsistence agriculture, as the main objective of commercial agriculture is achieving higher profits.

Farmers in both the core and the periphery have had to adjust to many changes that occurred at all levels, from the local to the global. Although states have become important players in the regulation and support of agriculture, at the global level, the World Trade Organization (WTO) has significant implications for agriculture. Social reactions to genetically engineered foods have repercussions throughout the world food system. Currently, the focus is especially on the option that a balanced, safe, and sustainable approach can be the solution not only to achieve sustainable intensification of crop productivity but also to protect the environment. Therefore, agriculture has become a highly complex, globally integrated system, and achieving the transformation to sustainable agriculture is a major challenge.

10.5 KEY TERMS DEFINED

agribusiness: commercial agriculture engaged in the production, processing, and distribution of food

agriculture: a science, art, and business directed to modify some specific portions of the Earth’s surface through the cultivation of crops and the raising of livestock for sustenance and profit

biofuels: fuel derived from biological materials

biorevolution: the genetic engineering of plants and animals with the potential to exceed the production of the Green Revolution

biotechnology: the manipulation through genetic engineering of living organisms or their components to make or modify products or processes for specific use

commercial agriculture: a system in which farmers produce crops and animals primarily for sale

conventional farming: agriculture that uses chemicals (fertilizers, pesticides, and herbicides) and/or hormone-based practices

crop rotation: method in which the field under cultivation remains the same, but the crop is changed to avoid exhausting the soil

double cropping: a method used in the milder climates in which intensive subsistence fields are planted and harvested twice per year

famine: an extreme scarcity of food

food regime: a specific set of links, indicating the ways a particular type of food is dominant during a specific time

food security: the situation when all people, at all times, have access to food for an active and healthy life

food sovereignty: the right of people, communities, and countries to define their own agricultural policies

globalized agriculture: agriculture increasingly influenced more at the global or regional levels than at the national level

genetically modified organisms (GMOs): organisms that have their DNA modified in a laboratory

Green Revolution: a new agricultural technology characterized by high-yield seeds and fertilizers exported from the core to the periphery to increase agricultural productivity

hunting and gathering: activities through which people obtain food from hunting wild animals, fishing, and gathering fruits, nuts, and roots

intensive subsistence agriculture: a form of subsistence agriculture in which farmers involve the effective and efficient use of small parcels of land to maximize crop yield per hectare

nontraditional agricultural exports: new export crops that contrast with traditional exports

organic farming: a method of crop and livestock production without commercial fertilizers, pesticides, growth hormones, and genetically modified organisms

pastoralism: subsistence activity that involves the breeding and herding of animals to satisfy the human needs of food, shelter, and clothing

pastoral nomadism: a traditional form of subsistence agriculture in which the pastoralists travel with their herds over long distances and with no fixed pattern

plantation: large landholdings in developing regions specialized in the production of one or two crops usually for export to more developed countries

ranching: a form of commercial agriculture in which the livestock graze over an extensive area

shifting cultivation: a form of subsistence agriculture, which involves a kind of natural rotation system

slash-and-burn agriculture: a method for obtaining more agricultural land in which fields are cleared (swidden) by slashing the vegetation and burning the debris

subsistence agriculture: farming designed to grow food only to sustain farmers and their families, consuming most of what they produce without entering into the cash economy of the country

sustainable agriculture: the efficient production of safe, high-quality agricultural products in a way that protects and improves the natural environment and the social and economic conditions of farmers and safeguards the health and welfare of all farmed species

swidden: land that is cleared for planting using the slash-and-burn process

transhumance: a seasonal vertical movement by herding the livestock to cooler, greener high-country pastures in the summer and returning them to lowland settings for fall and winter grazing

undernourishment/undernutrition: inadequate dietary consumption that is below the minimum requirement for maintaining a healthy life

10.6 WORKS CONSULTED AND FURTHER READING

Alexandratos, N., and Bruinsma, J. 2012. World agriculture towards 2030/2050. The 2012 revision. www.fao.org/docrep/016e/ap106e.pdf.

Bernstein, H. 2015. Food regimes and food regime analysis: A selective survey. https://www.iss.nl/fileadmin/ASSETS/iss/Research_and_projects/Research_ networks/LDPI/CMCP_1_Bernstein.pdf.

___. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Agricultural_biotechnology.

___. AGBIOS (Agriculture and Biotechnology Strategies). Database. http://www.agbios.com.

___. https://www.google.com/agricultural hearths.

___. 2008. Biofuel and food security. International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI). https://www.ifpri.org/publication/biofuels-and-food-security.

Brandt, K. 1967. Can food supply keep pace with population growth? Foundation for Economic Education (FEE). https://fee.org/articles.

Colman, D., and Nixon, F. 1986. Economics of change in less developed countries. 2nd Ed. Totowa, NJ: Barnes and Noble Books.

___. https://www.google.com/corn production.

___. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dairy_farming.

De Blij, H. J. 1995. The Earth: An introduction to its physical and human geography. 4E. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

De Blij, H. J., and Muller, P. 2010. Geography: Realms, regions, and concepts. 14 E. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Dickenson, J., Gould, B., Clarke, C., Marther, S., Siddle, D., Smith, C., and Thomas-Hope, E. 1996. A Geography of the Third World. Second edition. New York: Routledge.

Domosh, M., Neumann, R., and Price, P. Contemporary Human Geography: Culture, Globalization, Landscape. New York: W. H. Freeman and Company.

___. https://www.google.com/search?q=maps+world+agric+employment.

___. https://en.actualitix.com/country/wld/employment-in-agriculture.php/.

Evenson, R. 2008. Environmental planning for a sustainable food supply. In Toward a vision of land in 2015: International perspectives, ed. G. C. Cornia and J. Riddell, 285-305. Cambridge, MA: Lincoln Institute of Land Policy.

___. https://typesoffarming.wordpress.com/2016/01/21/what-are-the-main-types-offarming.

___. The state of food and agriculture: Climate change, agriculture, and food security. http://www.fao.org/3/a-i6132e.pdf.

___. The state of food insecurity in the world 2015. http://www.fao.org/3/ai4646e.pdf.

___. Protecting our food, farm, and environment. Center of Food Safety. http://www.centerforfoodsafety.org/.

___. Food security statistics. www.fao.org/economic/ess/ess-fs/en.

Friedmann, H. Food regimes and their transformation. Food Systems Academy. www.foodsystemsacademy.org.uk/audio/docs/HF1-Food-regime-Transcript. pdf.

___. Tulip Fields, Lisse, Netherlands. https://in.pinterest.com/pin/.

___. About genetically engineered food. Center for Food Safety. www. centerforfoodsafety.org/issues/311/ge-food/about-ge-foods.

___. Genetically modified foods. Learn. Genetics. Genetic Science Learning Center. http://learn.genetics.utah.edu/content/science/gmfoods/.

___. Genetically modified food. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Genetically_ modified_food.

___. GM food: Viewpoints. http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/harvest/viewpoints.

___. 2016. Global status of commercialized biotech/GM crops: Brief 52. ISAAA. www.isaaa.org/resources/publications/Brief/52/doawnload/isaaa-brief-52-2016.pdf.

___. How to avoid GMOs in your food. https://www.foodandwaterwatch.org/ live-healthy/how-avoid-gmos-your-food.

___. GMO: Labeling around the world. http://www.justlabelit.org/a-gmolabeling-around-the-world/.

___. Just label it: We have a right to know. http://www.justlabelit.org/rightto-know-center/right-to-know/.

Holt Giménez E, Shattuck A. Food crises, food regimes and food movements: rumblings of reform or tides of transformation? J Peasant Stud. 2011;38(1):109-44. doi: 10.1080/03066150.2010.538578. PMID: 21284237.

___. Commercial grain farming: Location and characteristics. www.yourarticlelibrary.com/family/commercial-grain-farming-location-andcharacteristics-with maps/25446.

Gruber, Carl. Hunter-Gatherer Men Not the Selfless Providers We Thought. March 31, 2016. http://www.australiangeographic.com.au/topics/history-culture/2016/03/ hunter-gatherer-men-not-the-selfless-providers-we-thought/.

___. Harvest of Fear. NOVA Frontline. DVD.

___. Herding: Pastoralism, mustering, droving. https://www.nationalgeographic.org/encyclopedia/herding.

___. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History-_of_agriculture

Hueston, W., and McLeod, A. Overview of the global food system: Changes over time/space and lessons for future food safety. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ books/NBK114491/.

___. Hunger. http://www.fao.org/hunger.en/.

___. Hunger Map. 2015. http://www.fao.org/3/a-i4674e.pdf.

___. https://wikipedia.org/wiki/hunter-gatherer.

___. Survival International. Accessed May 5, 2018. https://www.survivalinternational. org/tribes/congobasintribes/.

___. The Ifugao rice terraces. June 1, 2014. https://arlenemay.wordpress.com/2014/06/01/ the-banaue-rice-terraces/.

Knox, P., and Marston, S. 2013. Human Geography: Places and regions in a global context. Sixth Edition. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson.

___. ISAAA (International Service for the Acquisition of Agri-Biotech Applications). http://www.isaaa.org.

Lernoud, J., and Willer, H. 2017. Organic agriculture worldwide: Key results from the FIBL survey on organic agriculture worldwide. Research Institute of Organic Agriculture (FIBL), Frick, Switzerland. http://orgprints.org/3424/7/fibl-2017global-data-2015.pdf.

Magnan, A. 2012. Food regime. In The Oxford Handbook of Food History, ed. J. M. Pilcher. Oxford Handbooks Online. www.oxfordhandbooks.com/view/10.1093/ oxfordhb/9780199729937.001.0001/oxf

___. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Market_garden.

___. www.yourarticlelibrary.com/agriculture/mediterranean-agriculture-location-andcharacteristics-with-diagrams/25443.

___. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mixed-farming.

___. Characterization of mixed farms. www.fao.org/docrep/004/Y0501E/y0501e03.htm.

Nap, J.-P., Metz, P., Escaler, M., and Conner, A. 2003. The release of genetically modified crops into the environment. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12943539/

___. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Agriculture_in_New_Zealand.

___. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/wiki/Economy_of_New_Zealand.

___. The interactive map tracks obesity in the United States: 2013 U.S. adult obesity rate. https://www.sciencenews.org/article/interactive-map-tracks-obesity-unitedstates.

___. Organic area. http://faostat.fao.org/static/syb/syb_5000.pdf.

___. Organic farming by country. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Organic_ farming_by_country.

___. Organic farming statistics. http://www.fibl.en/themes/organic-farmingstatistics.html.

___. Organic universe. Down to Earth. Fortnightly of politics of development, environment, and health www.downtoearth.org.in/coverage/organicuniverse-38665.

___. Organic world: Global organic farming statistics and news. 2015. http://www.organic-world.net/statistics/statistics-data-tables.html.

___. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pastoralism.

Pulsipher, L. M. 2000. World Regional Geography. New York: W. H. Freeman and Company

___. Rancing. https://www.nationalgeographic.org/encyclopedia/rancing.

___. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ranch.

Roser, M., and Ritchie, H. Land use in agriculture. https://ourworldindata/ land-use-in-agriculture.

Rowntree, L., Lewis, M., Price, M., and Wyckoff, W. 2006. Diversity amid globalization: World regions, environment, development. 3rd Ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson.

Rubenstein, J. 2013. Contemporary Human Geography. 2e. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson.

Rubenstein, J. 2016. Contemporary Human Geography. 3e. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson.

___. Slash-and-burn farming in Congo. https://www.youtube.com/channel/ UCxM5DOEmlPN4rd9_Egj12pA/.

___. Intensive subsistence agriculture. www.yourarticlelibrary.com/ agriculture-intensive-subsistence-agriculture/44620.

___. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Subsistence_agriculture.

___. www.anthro.palomar.edu/subsistence/sub_3.htm.

___. Types of subsistence farming: Primitive and intensive subsistence farming. www.yourarticlelibrary.com/fg/types-of-subsistence-farming-primitive-andintensive-subsistence-farming/25457.

___. Sustainable agriculture initiative platform: The global food value chain initiative for sustainable agriculture. http://www.saiplatform.org/sustainableagriculture/definition.

Than, Ker. Climate change is linked to waterborne diseases in Inuit communities. April 7, 2012. https://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2012/04/120405-climate-changewaterborne-diseases-inuit/.

___. Chicago Board of Trade. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chicago_Board_ of_Trade/.

___. Transhumance. https://www.britannica.com/topic/transhumance.

___. www.medconsortium.org/projects/tranhumance.

___. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Transhumance.

True, J. 2005. Country before money? Economic globalization and national identity in New Zealand. In Economic nationalism in a globalizing world, ed. E. Helleiner and A. Pickel, Chapter 9. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. https://books.google.com/

Tyson, P. Should we grow GM crops? http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/harvest/ exist/www.fao.org/fileadmin/templates/FCIT/PDF/UPA-WBpaper-Final_ October_2008.pdf.

___. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Johann_Heinrich_von_Thunen.

___. https://www.google.com.wheat_production

World Bank. World Development Indicators: Agricultural inputs. wdi.worldbank.org/table/3.2

World Bank. 2015. Data Bank: World Development Indicators. Agricultural land. www://data.worldbank.org/indicator/AG.LND.AGRI.ZS?view=chart.

World Bank. 2016. Data Bank: World Development Indicators. Employment in agriculture. www://databank.worldbank.org/data/reports.aspx?source=SL.AGR.EMPL.ZS&country

10.7 ENDNOTES

- https://education.nationalgeographic.org/resource/genetically-modified-organisms/

- https://www.fao.org/fileadmin/templates/SOFI/2022/docs/map-fies-print.pdf