Chapter 11: Industry

David Dorrell; Todd Lindley; and Adam Dohrenwend

Figure 11.1 Factory in Katerini, Greece; Author | Jason Blackeye; Source | Wikimedia Commons; License | CC BY SA 4.0.

STUDENT LEARNING OUTCOMES

By the end of this section, the student will be able to:

Understand: the origins and diffusion of industrial production

Explain: the impact of industry on places

Describe: the industrial basis of modern cultures

Connect: industrialization, technology, the service sector, and globalization

CHAPTER OUTLINE

11.1 Introduction

11.2 Marx’s Ideas

11.3 Factors for Location

11.4 The Expansion and Decline of Industry

11.5 Global Production

11.6 Summary

11.7 Key Terms Defined

11.8 Works Consulted and Further Reading

11.9 Endnotes

11.1 INTRODUCTION

We live in a globalized world. Products are designed in one place and assembled in another from parts produced in multiple other places. These products are marketed nearly everywhere. Until a few decades ago, such a process would have been impossible. Two hundred years ago, such an idea would have been beyond comprehension. What happened to change the world in such a way? What eventually tied all the economies of the world into a global economy? Industry did. The Industrial Revolution changed the world as much as the Agricultural Revolution. The industry has made the modern lifestyle possible.

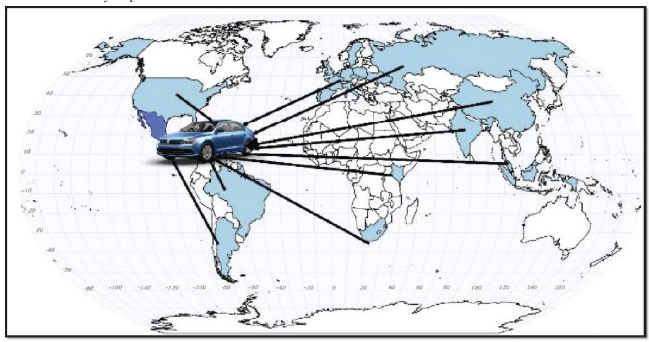

The Volkswagen Jetta is designed in Germany and assembled in Mexico from parts of the represented countries. It is marketed as “German-engineered.” Does it matter if the car was not made in Germany from German parts?

During the 2016 U.S. presidential election, something very peculiar happened. Candidates from both major parties (Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton) agreed over and over again on one thing (and only one thing). The U.S. needed to create and/or bring back manufacturing jobs. Both candidates promised, if elected, to create new, well-paid manufacturing jobs. This was an odd shift, because for the previous 40+ years, Republicans typically embraced free trade that allows manufacturers to choose where and what to produce (and many chose to move operations outside of the U.S.), while Democrats claimed to be working for the interests of blue-collar, working-class people, whose jobs and wages had diminished since the 1980s period of de-industrialization both in the U.S. and throughout the developed/industrialized world. In the U.S., manufacturing provided jobs to 13 million workers in 1950, rising to 20 million in 1980, but by 2017 that number was back to 12 million—similar to levels last seen in 1941. A similar story can be found in Great Britain, where jobs in manufacturing in 2017 were half of what they were in 1978, and output that once was 30% of GDP accounts for only 10% in 2017. Similar stories can be found in Germany, Japan, and other “industrialized” economies. You may ask yourself, “Where did all of those jobs go?” But if you think about it, you can probably come up with your answers.

It is important to note that even as jobs declined, manufacturing output in most industrialized countries continued to increase, so fewer people were producing more things. The first and simplest explanation for this is automation. For years, science fiction writers have warned us that the robots are coming. In the case of manufacturing technology…they are already here! Workers today are aided by software, robots, and sophisticated tools that have simply replaced millions of workers. Working at a manufacturing facility is no longer simply a labor-intensive effort, but one that requires extensive training, knowledge, and willingness to learn new technologies all the time. The second explanation is the relocation of manufacturing from wealthy countries to poorer ones because of lower wages in the latter.

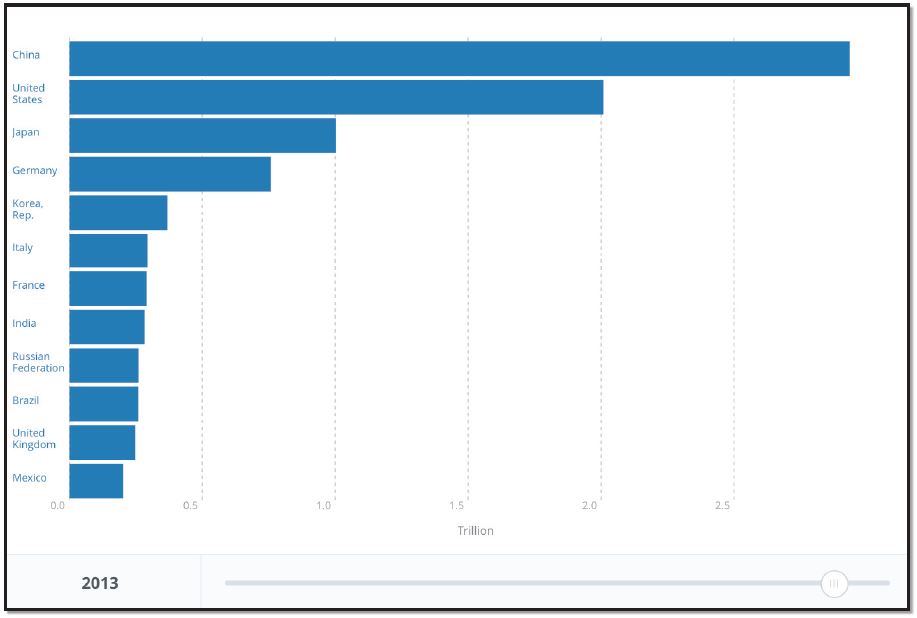

As discussed earlier in this chapter, most countries have moved away from the protectionist model of development, allowing corporations to choose for themselves the location of production. No better example of this shift can be found than Walmart, which in the 1970s advertised that the majority of all of the products it sold were made in the USA. Thirty years later, it would be difficult to find ANY manufactured product that was still “made in the USA.” A third reason for the decline in manufacturing jobs is a decrease in demand for certain types of items. Steel production in the U.S. and England dropped precipitously during the period of deindustrialization (since the 1980s) not just due to automation or cheaper wages elsewhere, but also because steel demand also declined. During the 20th century the U.S., Europe, and Japan required enormous amounts of steel in the construction of bridges, dams, railroads, skyscrapers, and even automobiles. Building such items in the 21st century has slowed down, not because those countries are in decline, but because there is a limit as to how many bridges and skyscrapers are needed in any country! Demand for steel in a country diminishes as GDP per capita reaches about $20,000. Meanwhile, steel demand will continue to rise in Japan and India for several years as they (and other industrializing countries) continue to expand cities, rail lines, and other large-scale construction projects. Such a decline in steel production does NOT mean that a country is in decline, but rather that there has been a shift in the type of manufacturing that occurs. The U.S., Germany, and Japan all continue to increase manufacturing output (Figure 11.3), even as their share of global output continues to decline.

Another significant shift in manufacturing relates specifically to the geography of production and is best understood in the consideration of 2 different modes of production: 1) Fordism and 2) Post-Fordism. Fordism is associated with the assembly line style of production credited to Henry Ford, who dramatically improved efficiency by instituting assembly line techniques to specialize/simplify jobs, standardize parts, reduce production errors, and keep wages high. Those techniques drove massive growth in manufacturing output throughout most of the 20th century and brought the cost of goods down to levels affordable to the masses. Nearly all of the automobile assembly plants located in and around the Great Lakes region of North America adopted the same strategies, which also provided healthy amounts of competition and innovation for decades, as North America became the world’s leading producer of automobiles. Post-Fordism began to take hold in the 1980s as a new, global mode of production that sought to relocate various components of production across multiple places, regions, and countries. Under Fordism, the entire unit would be produced locally, while Post-Fordism seeks the lowest cost location for every different component, no matter where that might be. Consider an optical, wireless mouse for a moment. The optical component may come from Korea, the rubber cord from Thailand, the plastic from Taiwan, and the patent from the U.S. Meanwhile, all of those items are most likely transported to China, where low-wage workers manually assemble the finished project and automated packing systems box and wrap it for shipping to all corners of the world. Global trade has been occurring for hundreds of years, dating back to the days of the Silk Road, Marco Polo, and the Dutch East India Company, but post-Fordism, in which a single item is comprised of multiple layers of manufacturing from multiple places around the world, is a very recent innovation. The system has reconfigured the globe, such that manufacturers are constantly searching for new locations for cheap production. Consumers tend to benefit greatly from the system in that even poor middle school students in the U.S. can somehow afford to own a pocket computer (smartphone) that is more powerful than the most advanced computer system in the world from the previous generation. This is kind of a miracle. On the other hand, manufacturing jobs that once were a pathway to upward economic mobility no longer assure people of such a decent standard of living as they once did.

11.1.2 History of Industrialization

Industrialization was not a process that emerged fully formed in England in the eighteenth century. It was the result of centuries of incremental developments that were assembled and deployed in the 18th century. Early industrialization involved using water power to run giant looms that produced cloth at a very low cost. This early manufacturing didn’t use coal and belch smoke into the sky, but it initiated an industrial mindset. Costs could be reduced by relying on inanimate power (first water, then steam, then electricity), converting production to simple steps that cheap low-skilled laborers could do (Taylorism), getting larger and concentrated in an area (economy of scale), and cranking out large numbers of the same thing (Fordism). This is the industry in a nutshell. The advantage of industry was that a company could sell a cheaper product but at a greater profit.

As this mindset was applied to other goods, and then services, the world was changed forever. Places that had been producing goods for millennia suddenly (really suddenly) found themselves competing with a far cheaper product. Economist Joseph Schumpeter coined the term “creative destruction” to describe the process in which new industries destroy old ones. Hand production of goods for the masses began to decline precipitously. They quickly became too expensive in comparison to manufactured goods. Today, hand-produced goods are often reserved for the wealthy.

A contemporary example of the industrial mode of production is fast food. Looking inside the kitchen of a fast food restaurant will reveal industrially prepared ingredients prepared just in time for sale to a customer. It is not the same process that you would use at home.

In the abstract, companies do not exist to provide jobs or even to make things. Companies exist to produce a profit. If changing the method of making a profit is necessary, then the company will do that to survive. If it cannot, then it will go away. For example, many companies today are highly diversified; Mitsubishi produces such unrelated products as cars and tuna fish. What is the connection between the two? They both produce a profit.

11.1.3 Industrial Geography

How is industry related to geography? For one thing, industrial societies have more goods in them. Since the goods are cheaper, people just have more things. For another, the means of production, the factories, shipping terminals, and distribution centers are visible for anyone to see. The lifestyles of industrialized people are different. Pre-industrialized societies are not regulated by clocks, for example; people wear mass-produced similar clothing. They listen to globally marketed music. If it seems like you already read this in the chapter on pop culture, you have. Pop culture is a function of industry. Geography is concerned with places and industries that changed the way the world operates. It changed the relationships between places. Places that industrialized early gained the ability to economically and politically dominate other parts of the world that had not industrialized. Something as simple as having access to cheap, mass-produced guns had impacts far beyond mere trade relationships.

Over time industrial production changed from one that disrupted local economies to one that completely changed the relationship that most human beings had with their material culture, their environment, and one another. Industry has improved standards of living and increased food production, on one hand, and it has despoiled environments and promoted massive inequality, on the other.

Industrialization is about applying rational thought to the production of goods. Specifically, this form of rational thought refers to discovering ways to reduce unnecessary labor, materials, capital (money), and time. In the same way that factories changed how things were produced, it also changed where things were produced. Locational criteria are used to determine where a factory even gets built.

11.2 MARX’S IDEAS

Karl Marx spent his working life trying to understand the nature of production. One of the things he noticed was that products have lifespans. When they are invented, they are new on the market and the producer has a monopoly. As soon as a product is released, competitors will quickly begin to provide alternative products at a lower price. The race begins to produce the product at an ever cheaper price, but also with an acceptable level of profit. This process occurs across both time and space as any mechanism possible to reduce the cost of manufacturing the product is discovered and used.

Advancements in materials will often occur. Instead of using a metal case, plastic may be good enough. A capital infusion may allow automation of the production. Eventually, after every other possibility to reduce costs is exhausted, the only way to maintain production is to cut labor costs. Few workers will accept a dramatic reduction in pay. It’s time to move the factory to a place with lower labor costs. Marx called this footloose capitalism. We call it offshoring. It’s the same thing, and it has always been part of capitalism. One aspect of this is that we who have grown up in a capitalistic world just naturally expect the price of goods to fall over time. In the United States we experienced a shift in manufacturing from the Northeast to the Midwest, then to the South and West. People in the United States have long moved to follow employment and only stopped doing so when it left the confines of the country.

11.3 FACTORS FOR LOCATION

Industrial location is a balance between capital, material, and labor and markets. The goal is the overall lowest cost. Sometimes pushing down one category, like labor, can increase other costs, like transportation. Substitution is possible across categories. For example, additional capital can replace labor through automation. Earlier factories were built in cities to use the labor that was available there. Building in the middle of nowhere could have created an immediate labor shortage. Of course, labor will also migrate to places with available employment.

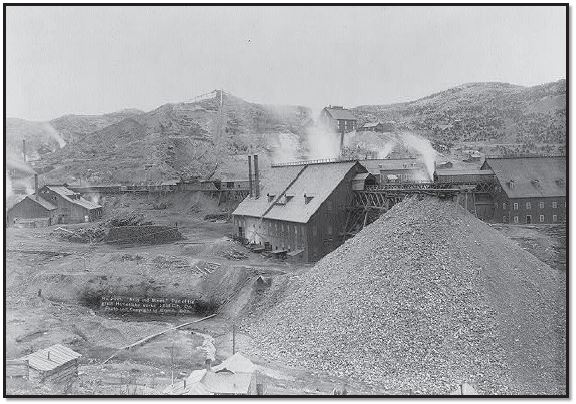

Some industrial activities are determined by the site, the physical characteristic of a location. If you want to have a coal mine, it is probably a good idea to locate in a place that has coal. This is the most extreme form of restriction, but bear in mind that many places have mineral wealth, but not all of them are extracting that wealth right now. Many places that would otherwise be candidates for resource extraction are not currently being used because the resources cannot be extracted and sold for a profit. If the resource cannot make money, it will not be used. Remember that government subsidies can make some resources more profitable than they normally would be.

Other industrial locations are products of their situation. The maquiladoras that line the southern side of the Rio Grande (Rio Bravo in Mexico) border would not be there if the United States were not on the other side of the river. The proximity to the United States is the determining characteristic in the choice to locate there. Industries moved to Mexico because it appeared to make economic sense to do so. They were able to lower labor costs while remaining within the US/Canadian market. Transportation costs increased initially, but transportation costs overall have fallen due to more efficient methods of moving goods. Were the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) to be revoked the situation of Mexico would change, their access to the markets of the United States and Canada would diminish, and the factories that are there would have a much harder time selling their goods.

11.3.1 Land (or Materials/Energy) Costs

Classic economics lumped raw materials and energy under the category of land. Few companies bother to buy the land that produces a particular material, nor do they generally invest in power generation or their oil fields. These inputs are subject to the same price pressures as every other part of the manufacturing process.

The land that a factory sits on has become less important over time. In earlier factories, most workers walked to work, and factories were compelled to locate on expensive land in cities. That is no longer the case. Due to the widespread diffusion of the automobile, factories can be built in more suburban or even rural areas, and workers will commute to the factory. This shifts part of the cost of securing labor onto the workers themselves. It lowers costs for the company. It is still necessary for the company to have access to the transport network, so new factories are usually built to take advantage of existing road networks, often next to interstates.

Sourcing materials has become global. Commodified inputs like steel are bought wherever they are relatively cheap and are shipped to where they are needed. Whichever source provider has the lowest cost, including shipping, will likely be chosen by the company. If you have ever bought something online, generally you want to know which company has the product with the lowest overall price. Companies operate the same way.

There are differences in energy costs across space. For energy-intensive industrial activities, cheap energy is essential. China rose from producing very little steel a few decades ago to leading the world today. It does this by leveraging low labor costs and a very cheap energy source—vast supplies of (highly polluting) coal.

11.3.2 Labor

Labor costs can be reduced in several ways. One way is simply to pay the workers that you have less money. Workers, however, do not like having their pay cut. Sending the work to a place with lower wages has been a common response to higher wages. A large portion of industrial labor requires minimal education. A company can choose to hire high school graduates in wealthy countries for a high wage or equivalently educated workers in poorer countries for far less. The labor pool has thus become globalized. Instead of competing for jobs with the other workers in a particular city, today’s workers are competing for jobs with much of the human population. Labor-intensive industries are particularly sensitive to labor costs. Clothing production has shifted to places with cheap labor as wages in developed countries have increased.

Besides the option of simply shipping jobs offshore, there is also the option of replacing workers outright. Most of the industrial jobs that have been lost in the United States in the last 30 years have not been to overseas production; they have been due to automation. Replacing people with machines is as old as the industry itself. The difference now is that machines are much more capable than they were in the past, and they are much cheaper. Referencing the earlier example of clothing manufacture, the production of athletic shirts in the United States got a large boost with the introduction of a factory in Little Rock, Arkansas, that relies on a robot called Sewbot. The factory will produce millions of shirts at very low costs ($.33 in labor per shirt). This low cost of labor renders it nearly negligible in importance compared to other factors, such as transporting the materials to the factory and transporting the finished clothes to market. The factory was built by a Chinese company in the center of the United States to minimize transport costs. More factories will likely migrate nearer their markets as the cost of labor becomes less important. Developed countries are already seeing an expansion of manufacturing, but not an expansion of manufacturing employment, due to the influence of automation.

11.3.3 Transportation

An important contributor to geographic thinking regarding industrial locations was Alfred Weber (1868–1958). Weber took the concept of using the lowest overall cost for the locations of the industry and expanded it. He developed models that held many inputs to manufacturing constant to demonstrate the importance of transportation in determining the least cost.

Weber believed that transportation costs were the most relevant factor in determining the location of an industry. The best way to minimize the cost of transport depends on the raw materials being transported. There are two kinds of raw materials, things that are more-or-less everywhere (ubiquitous) and local raw materials. For ubiquitous material (e.g. water), you have more freedom to locate because it’s commonly available. In this case, you should build your facility near your market, then you won’t need to transport much. We see examples of this in the locations of breweries and soft drink manufacturers.

On the other hand, if the material is only in a particular place (like bauxite), then you have some calculating to do. First, you need to figure out if your manufacturing condenses, distills, or otherwise shrinks your material. We call these processes bulk-reducing. If you are not doing that, but instead take small pieces and assemble them into something harder to transport (like a tractor), then it is called bulk-gaining. To minimize transport costs for bulk-reducing activities, you want to process them as close as possible to their extraction site. Examples of this are metal smelters and lumber mills.

Bulk-gaining processes are a little more complicated. You need to find the least cost point between your source materials (which may be numerous) and your market. Remember that the goal is the overall lowest cost, so that involves many calculations to determine which is the cheapest location, meaning your location might be in between several of your inputs and/or markets. A general rule of this is that these sorts of businesses tend to be fairly close to their final markets.

There were two last considerations that Weber discussed, agglomeration and deagglomeration. Weber called them secondary factors because they were less important than the previously mentioned characteristics. Agglomeration is related to the idea of economy of scale. Sometimes there are advantages to having similar industries near one another. Consider the manufacture of computers. Computer manufacturers don’t make their components; they buy them, and they use similar tools to put them together, and they use similar labor, and so forth. When industries concentrate in a place they can share some resources and split the cost. This is not to say that this is a conscious process; in many instances, it just develops on its own. Deglomerative factors produce diseconomies of scale and are responsible for the redistribution of industry. Examples of this could be escalating prices for land or labor which drive production away from an area.

This is a photo of a lead mine in South Dakota in the 19th Century. Notice the large piles of waste material left behind.

11.3.4 Reducing Transportation Costs

Containerization has greatly changed the nature and cost of transportation. In the past, transporting goods required large numbers of people to move goods around. People loaded and unloaded goods at break-of-bulk points. Break-of-bulk points were places like railroad terminals, where goods were loaded onto trains, or ports, where goods were loaded into ships. Break-of-bulk points had large numbers of people loading and unloading items. Containerization changed that process tremendously. Goods are now packed into large metal boxes, and then the boxes are moved from point to point. Cranes move the boxes from trucks to trains to ships, then reverse the process at the shipping destination. Intermodal transportation assumes that a container will seamlessly be transported by any number of different shipping methods. The number of people necessary to ship goods plummeted. The speed at which goods moved increased tremendously since the bottlenecks were removed from the system. Containerization is a good example of an innovation that did not require a large technological shift; it simply required rationalizing a labor-intensive system. Logistics, the commercial activity of transporting goods, is the glue that holds the global production network together. Without relatively inexpensive shipping, many offshored industries would not be able to make goods in distant factories, ship them to other places, and still make a profit.

Uniform size and shape allow for rapid transport and sorting at minimal cost.

11.3.5 Reducing Capital Costs

Operating an industry has more costs than materials, labor, and shipping. Other factors such as taxes, regulatory compliance, and financial incentive packages can either attract or repel manufacturing. These factors increased tremendously in importance. It has become possible for many industries to ignite a “bidding war” to secure increasingly advantageous incentives to locate in a particular place. Tax breaks, construction allowances, and other benefits will be paid by the places that desperately struggle to attract industries. This has triggered what has been described as a race for the bottom as places promise more than they can afford in the hopes of securing outside investment. Another consideration is access to capital. Businesses often need investment funds or short-term credit. Being unable to secure capital prevents many businesses in developing countries from starting or continuing. Countries without banking infrastructure find it nearly impossible to raise sufficient money to develop their industries. Companies in countries like this are forced to hunt for financial backing in other countries.

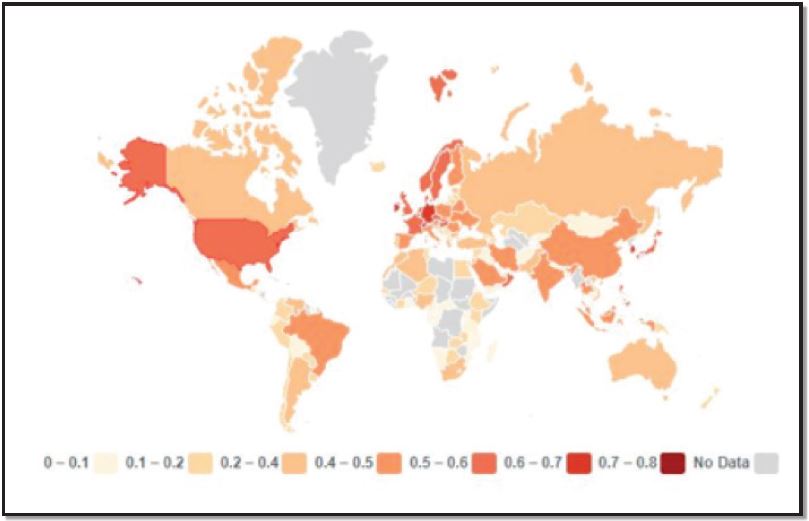

11.3.6 Risk

Industries have large sunk costs. Corruption can take advantage of this to demand bribes, protection money, or other expenses that siphon off profit. High levels of corruption inhibit investment. Industries are risk-averse. Politically unstable places will also have difficulty industrializing since companies will be reluctant to build in places where any investment could be lost in a revolution or other political violence. This doesn’t mean that industry requires representative government. Many places have experienced tremendous economic development without democracy. It just means that companies have to feel that any money that they invest in a place is safe.

11.3.7 Accessing a Market

One of the interesting examples of this concept is the number of foreign companies that establish themselves in the United States. Companies such as Foxconn (Taiwan), Hyundai (Korea), and BMW (Germany) build products in the United States. A good question to ask yourself would be “Why do they do that?” It turns out that locating in the United States is advantageous for them. First, they can reduce shipping costs; we have already addressed that. Second, although labor in the United States is relatively expensive, it’s not appreciably different than in their home markets. Third, they may be able to avoid tariffs on imports. Finally, being in the United States places these products near a large market. The North American market is very large, and being embedded in it can be advantageous for some companies.

11.4 THE EXPANSION (AND EVENTUAL DECLINE) OF INDUSTRY

11.4.1 Transnational Corporations

Modern industry has become dominated by transnational corporations. Transnational corporations (TNCs) can coordinate and control various processes and transactions within production networks, both within and between different countries. They also can take advantage of geographical differences in factors of production and state policies. Potential geographical flexibility for sales is a final benefit.

Foreign direct investment (FDI) is exactly what it sounds like. Companies invest in other countries. The usual narrative of this in the United States is simply offshoring for cheaper labor. The reality is more complicated. Just consider the examples above of the manufacturers who build facilities in the United States. They aren’t seeking cheap labor. American companies moving production may be seeking to tap into a large pool of labor, but that labor is not as cheap as it was 20 years ago. Another reason for investing in China is the same reason that other companies invest here in North America, to gain entry into a large market. Companies and individuals investing in other countries have numerous motivations. Some of these motivations are altruistic. There is no shortage of entities that seek to use FDI as a mechanism to alleviate poverty. The earlier critique of financial incentives applies directly to foreign direct investment, for obvious reasons. Poor and desperate places will sometimes make economic decisions that make little economic sense.

FDI has an established history. Initially, companies in wealthy countries were mostly interested in extracting raw materials from other, usually poorer, countries. This continues to this day. Countries like Niger, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and Venezuela function almost solely as a source of inputs for other companies based in other countries. Other places have seen investment in factories. Sometimes this is due to very low-cost labor, but in many instances, it is because their wages are relatively low and they are relatively close to their market. An example of this was seen in Eastern Europe when many of these countries entered the European Union.

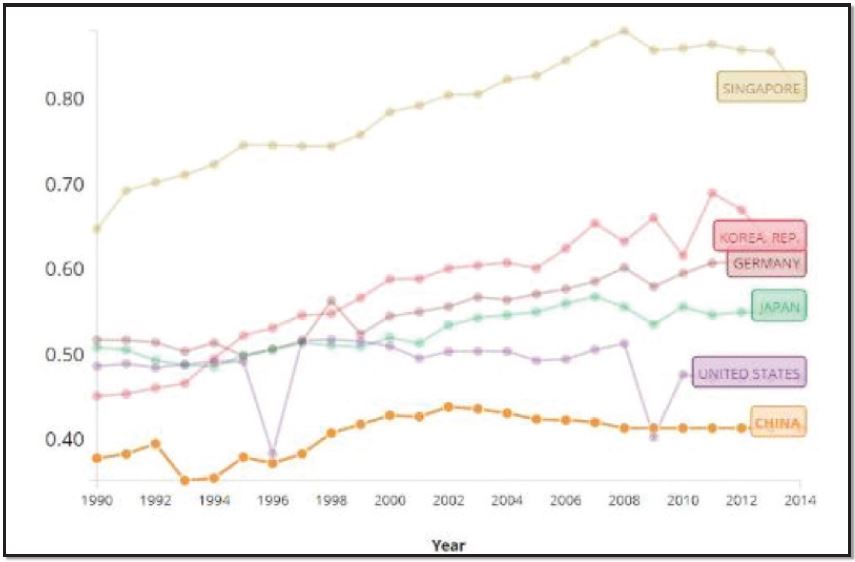

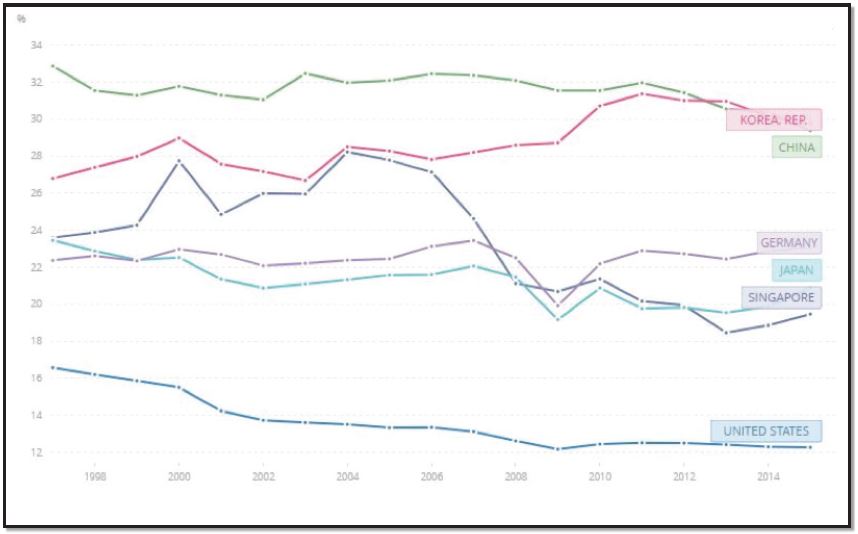

The next graph is slightly different. It shows the different trajectories of manufacturing in general as part of a country’s economy. As you can see, manufacturing as a share of GDP in the United States has been quite low for some time. Manufacturing in China and Korea is much more important, but in both these places, the relative value of manufacturing is falling. In Germany, Japan, and Singapore, the value of manufacturing is rising, although at very moderate levels. Note that neither of these graphs accounts for wages produced from manufacturing employment.

11.5 GLOBAL PRODUCTION

11.5.1 Hegemony and Economic Ascendency

At times industrialization has propelled countries to great economic heights. Britain, the United States, and Japan all rode an industrial wave to international prominence. In those countries and others, a (largely mythical) golden age centers around a time when low-skilled workers could earn a sufficient wage to secure economic security. This is more-or-less what the “American Dream” was. Deindustrialization has changed the economic trajectories of these countries and the people living in these countries. However, it must be noted that post-industrial countries that have not seen rapid increases in poverty. Wages have been largely stagnant for decades, but they have not generally gone down. The largest difference has to do with the relative prosperity of industrial and post-industrial countries. Countries such as Japan, the UK, or the US are no longer far wealthier than their neighbors. In the same way that flooding a market with a particular product reduces the value of that product, flooding the world with industrial capacity lowers the relative value of that activity. Developing countries function as appendages to the larger economies in the world. The poor serve the needs of the wealthy. Unindustrialized countries buy goods from developed countries, or they license or copy technology and make the products themselves.

11.5.2 Space and Production

In the context of a globalized market, a factory built in one market may not be built in another. This is not to say that producing goods is a zero-sum game, but there are limits to the amount of any good that can be sold. It’s a valid question to ask why transnational corporations (TNCs) have bought into China at rates far greater than in Cuba, Russia, or other Communist or formerly Communist (to varying degrees) countries. There is only so much spare capacity for production in the world. If one giant country (China) is taking all the extra capacity, then there will be none left for others. FDI is simply easier in China since there is more bang for the buck. This is largely a function of population. The population of China is roughly two times the population of Sub-Saharan Africa, and China has a single political/economic running class, as opposed to 55 different sets of often fractious political classes. If the industrialization of Africa happens at all, it will occur after China and its immediate neighbors who have been drawn into its larger economic functioning have largely finished their industrializing. An example of this proximate effect is seen in the shift of some industries from China to Vietnam and Indonesia.

China’s industrialization had to do with promoting itself as a huge cheap labor pool and as a gigantic market for goods. It successfully leveraged both of these characteristics to attract foreign investment and to gain foreign technology from the companies that have invested in producing goods there. Industrialization overall seems to have slowed. The speed at which China industrialized has not been matched by other countries following China. One current idea is that the world is in a race between industrial expansion and rapid overcapacity of production. In other words, the reason that industrialization isn’t expanding as rapidly as before is that we are already making enough goods to satisfy demand. Remember that goods require demand. Unsold goods don’t produce any income. If the factories in the world are already producing enough, or even too much, then new factories are much less likely to be built. Technological advances and the massive industrialization of China might have ended the expansion of industry.

It also appears that the highest levels of manufacturing income are well in the past. According to economist Dani Rodrik, the highest per capita income from manufacturing occurred between 1965 and 1975 and has fallen dramatically since then. This is even considering inflation. Many countries industrializing now only see modest improvements in income. This is related to supply and demand. When there are fewer factories, they make comparatively more money. When factories are everywhere, they are competing with everyone.

11.5.3 Trade

Even more than the expansion of industrial production, the world has seen an expansion of trade. Global trade has produced an intricate web of exchanges as products are now designed in one country, parts are produced in 10 others, assembled in yet another country, and then marketed to the world. Consider something as complex as an automobile. The parts of a car can be sourced from any of dozens of countries, but they all have to be brought to one spot for assembly. Such coordination would have been impossible in the past.

Individuals can buy directly from another country on the Internet, but most international trade is business-to-business. TNCs can conduct an internal form of international trade in goods that can be moved and produced in a way that is most advantageous for the company. Tax breaks, easy credit, and banking privacy laws exist to siphon investment from one place to another.

Because of global trade, improvements in communication and transportation have enabled some companies to enact just-in-time delivery, in which the parts needed for a product only arrive right before they are needed. The advantage of this is that a company has less money trapped in components in a storage facility, and it becomes easier to adjust production. Once again, such coordination at a global scale was not possible even in the relatively recent past.

11.5.4 Deindustrialization

Historically industrialized countries were the wealthy countries of the world. Industrialization, however, is now two centuries old. In the last decades of the twentieth century, deindustrialization began in earnest in the United Kingdom, the United States, and many other places. Factories left and the old jobs left with them. Classical economics holds that such jobs had become less valuable and that moving them offshore was a good deal for everyone. Offshored goods were cheaper for consumers, and the lost jobs were replaced by better jobs. The problem with this idea is that it separates the condition of being a consumer from the condition of being a worker. Most people in any economy are workers. They can only consume as long as they have an income, and that is tied to their ability to work. Many workers whose jobs went elsewhere found that their new jobs paid less than their old jobs.

11.5.5 What Happens After Deindustrialization?

The simple answer to the above question is this. The service economy happens! As manufacturing provides fewer jobs, service industries tend to create new jobs. This is a very delicate balance, however. If you are a 50-year-old coal miner whose job has been eliminated by automation, it is very difficult for you to simply change jobs and enter the “service sector.” This transition is very damaging to those without the right skills, training, education, or geographic location. Many parts of the American Midwest, for example, have become known as the “rust belt” as industrial facilities closed, decayed, and rusted to the horror of those residents who once had good jobs there. The city of Detroit, for example, lost nearly half of its urban population from 1970 to 2010. Meanwhile, the state of Illinois loses one resident every 15 minutes as job growth has weakened in the post-industrial age. However, job growth and productivity in the service economy have strengthened and provide more job opportunities today than the industrial era ever did in the U.S.

There are 3 sectors of every economy:

- Primary (agriculture, fishing, and mining)

- Secondary (manufacturing and construction)

- Tertiary (service-related jobs)

The vast majority of economic growth in the post-industrialized world comes in the tertiary sector. This doesn’t mean that all tertiary jobs pay well. Just ask any fast-food worker if the service sector is making them rich! However, service sector jobs are very dynamic and offer tangible opportunities to millions of people around the world to earn a living providing services to somebody else. We can further break down the service sector into 1) public (the post office, public utilities, working for the government), 2) business (businesses providing services to other businesses), and 3) consumer (anything that provides a service to a private consumer; e.g. hotels, restaurants, barber shops, mechanics, financial services).

Traditionally, service sector jobs worked very much like manufacturing jobs in that employees worked regular hours, earned benefits from the employer, gained raises through increased performance, and went to work somewhere outside of their home. Many service jobs in the 21st century, however, have been categorized as the gig economy, in which workers serve as contractors (rather than employees), have no regular work schedules, don’t earn benefits, and often work in isolation from other workers rather than as a part of a team. Examples of “jobs” in the gig economy include private tutor, Uber/Lyft driver, Airbnb host, blogger, and YouTuber.

Work, in this economy, is not necessarily bound by particular places and spaces in the way that it is in manufacturing. Imagine a steel worker calling in to tell his/her boss that they are just going to work from home today! Even public schools have adapted to this model in the following manner. As schools cancel classes due to weather, the new norm is to hold classes online, whereby students do independent work submitted to the teacher even though nobody is at school. As such, some workers are freed up from the traditional constraints of time and place and can choose to live anywhere as long as they maintain access to a computer and the Internet. Services like Fiverr.com facilitate a marketplace for freelance writers to compose essays for others or for graphic artists to sell their design ideas directly to customers without ever meeting one another.

The global marketplace continues to be defined as a place where the traditional relationships between employer and employee are changing dramatically. A word of caution is necessary here, however. As many choose to celebrate the freedom that accompanies flexible work schedules, there is also a darker side in that the traditional “contract” and social cohesive element between workers and owners is very much at risk. One defining factor of the 20th century was the development of civil society that fought for and won a host of protective measures for workers, who otherwise could face abusive work conditions. Child labor laws, minimum wage, environmental safety measures, overtime pay, and guards against discrimination were all based upon an employer-employee relationship that seems increasingly threatened by the gig economy. Uber drivers can work themselves to exhaustion since they are not employees. Airbnb hosts can skirt environmental safety precautions since they do not face the same safety inspections required at hotels. These are just a few examples, but they are very worth consideration. Regardless of the positives and negatives, the new service economy is having a transformative effect on all facets of society. Although the authors of this textbook are all geography professors with Ph.D.s from a variety of universities, perhaps the next version of this textbook will simply draw upon the gig economy to seek the lowest-cost authors who are willing to write about all things geographical. Will you be able to tell the difference? (We hope so!!!)

11.6 SUMMARY

Industrial production changed the relationship of people to their environments. Folk (pre-industrial) cultures used local resources and knowledge to hand-produce goods. Now the production of goods and the provisioning of services can be split into innumerable spatially discrete pieces. Competition drives the costs of goods and services downward, providing relentless pressure to cut costs. This process has pushed industrialization into most corners of the world as companies have looked further and further afield to find cheaper labor and materials and to find more customers. Industrialization has fueled a lifestyle change; as goods have become cheaper, they have become more accessible to more people. Our lives have changed. We now live according to a schedule dictated by international production.

11.7 KEY TERMS DEFINED

Back office services – interoffice services involving personnel who do not interact directly with clients.

Break-of-bulk point – a point of transfer from one form of transport to another.

Bulk reducing – an industrial activity that produces a product that weighs less than the inputs.

Commodification – the process of transforming a cultural activity into a saleable product.

Containerization – a transport system using standardized shipping containers.

Deindustrialization – the process of shifting from a manufacturing-based economy to one based on other economic activities.

Economies of scale – efficiencies in production gained from operating at a larger scale.

Footloose capitalism – spatial flexibility of production.

Fordism – a rational form of mass production for standardizing and simplifying production.

Gig economy – a labor market characterized by freelance work.

Globalization – the state in which economic and cultural systems have become global in scale.

Intermodal – a transportation system using more than one mode of transport.

Just-in-time delivery – a manufacturing system in which components are delivered just before they are needed to reduce inventory and storage costs.

Locational criteria – factors determining whether an economic activity will occur in a place.

Logistics – the coordination of complex operations.

Outsourcing – shifting the production of a good or the provision of a service from within a company to an external source.

Offshoring – shifting the production of a good or the provision of a service to another country.

Supply chain – all products and processes involved in the production of goods.

Taylorism – the scientific management of production.

11.8 WORKS CONSULTED AND FURTHER READINGS

Berkhout, Esmé. 2016. “Tax Battles: The Dangerous Global Race to the Bottom on Corporate Tax,” 46.

Dicken, Peter. 2014. Global Shift: Mapping the Changing Contours of the World Economy. SAGE.

Dorrell, David. 2018. “Using International Content in an Introductory Human Geography Course.” In Curriculum Internationalization and the Future of Education.

Goodwin, Michael, David Bach, and Joel Bakan. 2012. Economix: How and Why Our Economy Works (and Doesn’t Work) in Words and Pictures. New York: Harry N. Abrams.

Grabill, John C. H. 1889. “‘Mills and Mines.’ Part of the Great Homestake Works, Lead City, Dak.” Still image. 1889. http://www.loc.gov/pictures/resource/ppmsc.02674.

Gregory, Derek, ed. 2009. The Dictionary of Human Geography. 5th ed. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Griswold, Daniel. n.d. “Globalization Isn’t Killing Factory Jobs. Trade Is Actually Why Manufacturing Is up 40%.” Latimes.com. Accessed April 21, 2018. http://www.latimes.com/opinion/op-ed/la-oe-griswold-globalization-and-trade-help-manufacturing-20160801-snap-story.html.

Howe, Jeff. 2006. “The Rise of Crowdsourcing.” WIRED. 2006. https://www.wired.com/2006/06/crowds/.

Massey, Doreen B. 1995. Spatial Divisions of Labor: Social Structures and the Geography of Production. Psychology Press.

Rendall, Matthew. 2016. “Industrial Robots Will Replace Manufacturing Jobs — and That’s a Good Thing.” TechCrunch (blog). October 9, 2016. http://social.techcrunch.com/2016/10/09/industrial-robots-will-replace-manufacturing-jobs-and-thats-a-good-thing/.

Rodrik, Dani. 2015. “Premature Deindustrialization.” Working Paper 20935. National Bureau of Economic Research. https://doi.org/10.3386/w20935.

Sherman, Len. 2017. “Why Can’t Uber Make Money?” December 14, 2017. https://www.forbes.com/sites/lensherman/2017/12/14/why-cant-uber-make-money/#2fb5abc10ec1.

Sumner, Andrew. 2005. “Is Foreign Direct Investment Good for the Poor? A Review and Stocktake.” Development in Practice 15 (3–4): 269–85. https://doi.org/10.1080/09614520500076183.

Zhou, May, and Zhang Yuan. 2017. “Textile Companies Go High Tech in Arkansas – USA – Chinadaily.Com.Cn.” July 25, 2017. http://usa.chinadaily.com.cn/world/2017-07/25/content_30244657.htm?utm_campaign=T-shirt%20%20line&utm_source=hs_email&utm_medium=email&utm_content=54911122&_hsenc=p2ANqtz-9WyxMiFliVTrpO35Quk5KN0XpHHHj2bYn9-7WKp3Tt_iF8LUsO9Q6m6OEH892iW9QcXJ4kvAk8C1Ooiy5TffzH6URrPVnKTrvZ3TEFQ_zyt6rIjp0&_hsmi=54911122

11.9 ENDNOTES

- Data source: World Bank. https://tcdata360.worldbank.org

Media Attributions

- Figure 11.1

- VW Jetta