Chapter 12: Human Settlements

Georgeta Connor and Juana Ibáñez

STUDENT LEARNING OUTCOMES

By the end of this section, the student will be able to:

- Understand: the similarities and differences between rural and urban

- Explain: urban origins and how the earliest settlements developed independently in the various hearth areas

- Describe: the models of rural and urban structure, comparing and contrasting urban patterns in different regions of the world

- Connect: the nature and causes of the problems associated with overurbanization in developing countries

CHAPTER OUTLINE

- 12.1 Introduction

- 12.2 Rural Settlement Patterns

- 12.3 Urbanization

- 12.4 Urban Patterns

- 12.5 Summary

- 12.6 Works Consulted and Further Reading

- 12.7 Endnotes

12.1 INTRODUCTION

Rural areas cover a multitude of natural and cultural landscapes. Natural areas include forests, parks, and wilderness zones. Cultural landscapes include agricultural fields, villages, educational centers, commercial sites, and the infrastructure connecting places. Rural areas fulfill significant balance functions between unpopulated wilderness zones and overloaded centers of dense development. Because of this complex diversity, our understanding of rural areas must consider more than how land is used by nature and humans. That is, our understanding must also encompass the economic and social structures in rural areas in which farming and forestry, handicraft, and small, middle, or large companies produce and trade, where services, from the most local to the most international (such as tourism), are provided. In addition, some rural areas represent valuable ecological balance zones through preservation and/or conservation establishments. All these factors create and evolve into a tight interdependence, interconnection, and competition.

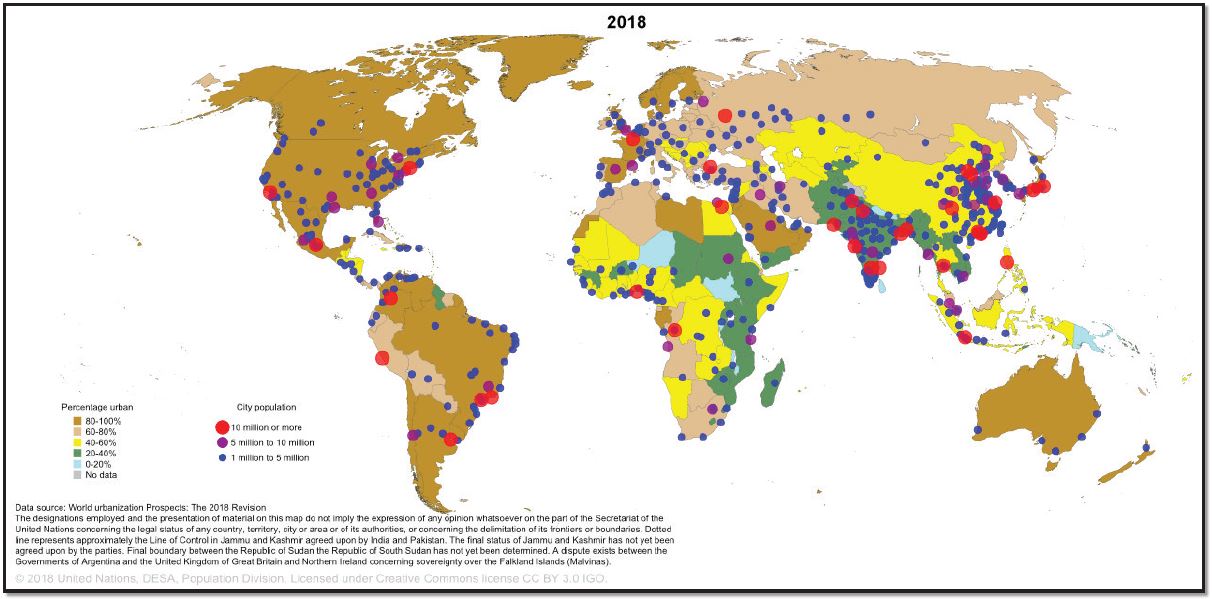

Today, over 57 percent of the world's population2 lives in urban areas, and the proportion of the urban population is growing at a rapid rate. Thus, urbanization is an important geographic phenomenon in today’s world. Towns and cities are in constant flux. Historically, cities have been influenced by technological developments such as the steam engine, railroads, the internal combustion engine, air transport, electronics, telecommunications, robotics, and the internet. As a result of the increased population and the global shift to technological-, industrial-, and service-based economies, the growth of cities and urbanization of rural areas will continue.

Within the cities of the developed world, the economic reorganization has resulted in a selective recentralization of residential and commercial land use. Industrial decentralization is prevalent. In contrast to the core regions, where urbanization has largely resulted from economic growth, the urbanization of peripheral regions has been a consequence of demographic growth, generating large increases in population (overurbanization) well in advance of any significant levels of urban or rural economic development. Luxury homes and apartment complexes, corresponding with a dynamic formal sector of the economy, contrast sharply with the slums and squatter settlements of people who are working in the informal (not regulated by the state) sector.

12.2 RURAL SETTLEMENT PATTERNS

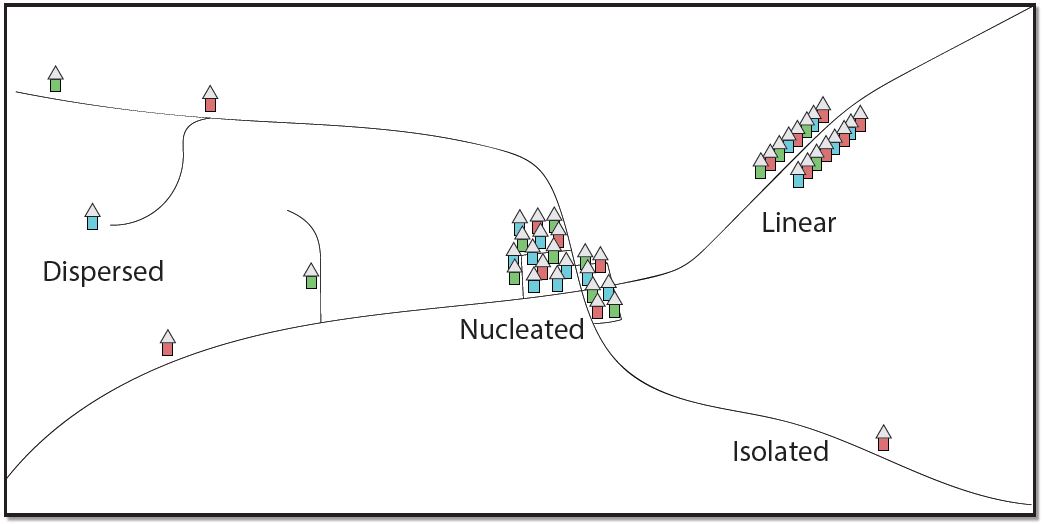

There are many types of rural settlements. Settlements can be classified into two broad categories: clustered and dispersed. To determine which, the classification criteria include the shape, internal structure, and street pattern of the settlement.

12.2.1 Clustered Rural Settlements

A clustered rural settlement is a rural settlement where several families live near each other, with fields surrounding the collection of houses and farm buildings. The layout of this type of village reflects historical circumstances, the nature of the land, economic conditions, and local cultural characteristics. The rural settlement patterns range from compact to linear and from circular to grid.

12.2.1.1 Compact Rural Settlements

This model has a center where several public buildings are located such as the community hall, bank, commercial complex, school, and church. This center is surrounded by houses and farmland. Small garden plots are located in the first ring surrounding the houses, continued with large cultivated land areas, pastures, and woodlands in successive rings. The compact villages are located either in plain areas with important water resources or in some hilly and mountainous depressions. In some cases, the compact villages are designed to conserve land for farming, standing in sharp contrast to the often isolated farms of the American Great Plains or Australia (Figure 12.1).

12.2.1.2 Linear Rural Settlements

The linear form is comprised of buildings along a road, river, dike, or seacoast. Excluding the mountainous zones, the agricultural land is extended behind the buildings. The river can supply the people with a water source and the availability to travel and communicate. Roads are constructed in parallel to the river for access to inland farms. In this way, a new linear settlement can emerge along each road, parallel to the original riverfront settlement (Figure 12.2).

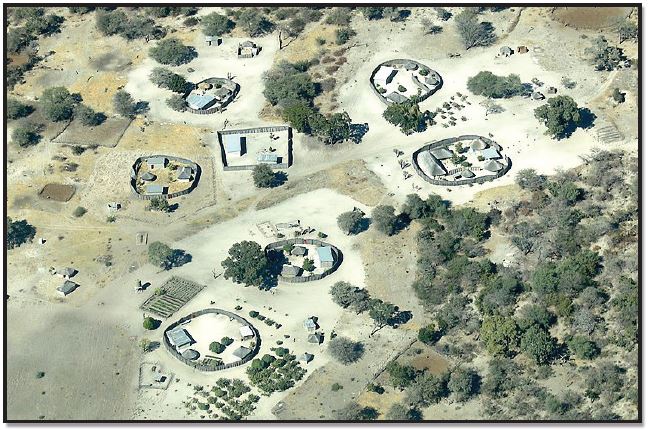

12.2.1.3 Circular Rural Settlements

This form consists of a central open space surrounded by structures. Such settlements are variously referred to as a Rundling, Runddorf, Rundlingsdorf, Rundplatzdorf or Platzdorf (Germany), Circulades and Bastides (France), or Kraal (Africa). There are no contemporary historical records of the founding of these circular villages, but a consensus has arisen in recent decades. The current leading theory is that Rundlinge was developed at more or less the same time in the 12th century as a model developed by the Germanic nobility as suitable for small groups of mainly Slavic farm settlers. Also, in medieval times, villages in the Languedoc, France, were often situated on hilltops and built circularly for defensive purposes (Figures 12.3 and 12.4).

Although far from the German territory, Romania has a unique, circular German village. Located in southwestern Romania, Charlottenburg is the only round village in the country. The village was established around 1770 by Swabians who came to the region as part of the second wave of German colonization. In the middle of the village is a covered well surrounded by a perfect circle of mulberry trees behind which are houses with stables, barns, and their gardens in the external ring. Due to its uniqueness, the beautiful village plan from the Baroque era has been preserved as a historical monument (Figure 12.5).

12.2.2 Dispersed Rural Settlements

A dispersed settlement is one of the main types of settlement patterns used to classify rural settlements. Typically, in stark contrast to a nucleated, or compact, settlement, dispersed settlements range from a scattered to an isolated pattern (Figure 12.6). In addition to Western Europe, dispersed patterns of settlements are found in many other world regions, including North America.

12.2.2.1 Scattered Rural Settlements

A scattered dispersed type of rural settlement is generally found in a variety of landforms, such as the foothill, tableland, and upland regions. The most common scattered village is found at the highest elevations and reflects the rugged terrain and pastoral economic life. The population maintains many traditional features in architecture, dress, and social customs, and the old market centers are still important. Small plots and dwellings are carved out of the forests and on the upland pastures wherever physical conditions permit. Mining, livestock raising, and agriculture are the main economic activities, the latter characterized by terrace cultivation on the mountain slopes. The sub-mountain regions, with hills and valleys covered by plowed fields, vineyards, orchards, and pastures, also have this type of settlement.

12.2.2.2 Isolated Rural Settlements

This isolated form consists of separate farmsteads scattered throughout the area in which farmers live on individual farms isolated from neighbors rather than alongside other farmers in settlements. The isolated settlement pattern is dominant in rural areas of the United States, but it is also an important characteristic for Canada, Australia, Europe, and other regions. In the United States, the dispersed settlement pattern was developed first in the Middle Atlantic colonies as a result of the individual immigrants’ arrivals. As people started to move westward, where land was plentiful, the isolated type of settlements became dominant in the American Midwest. These farms are located in the large plains and plateaus agricultural areas, but some isolated farms, including hamlets, can also be found in different mountainous areas (Figures 12.7 and 12.8).

12.3 URBANIZATION

12.3.1 Urban Origins

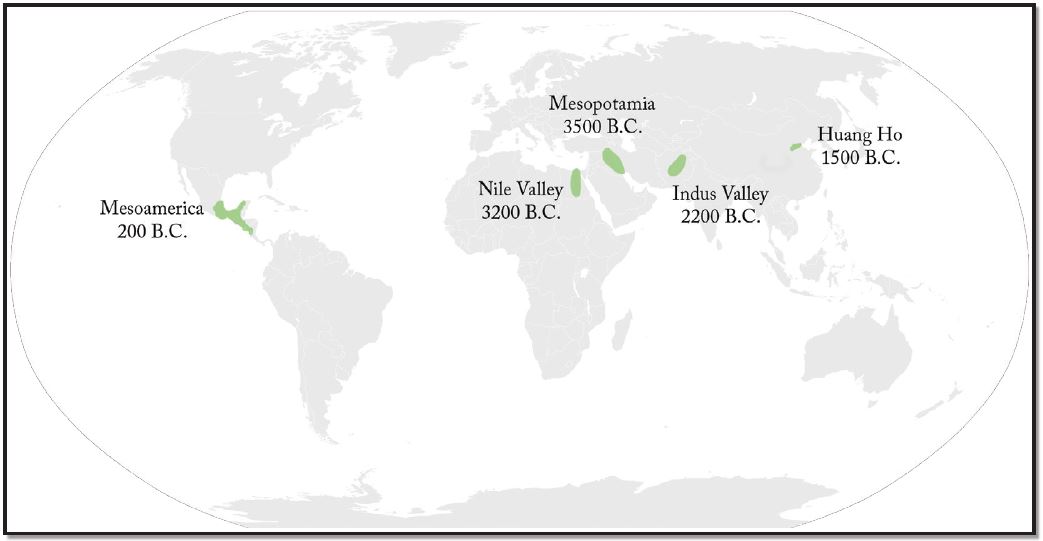

The earliest towns and cities developed independently in the various regions of the world. These hearth areas have experienced their first agricultural revolution, characterized by the transition from hunting and gathering to agricultural food production. Five world regions are considered as hearth areas, providing the earliest evidence for urbanization: Mesopotamia and Egypt (both parts of the Fertile Crescent of Southwest Asia), the Indus Valley, Northern China, and Mesoamerica (Figure 12.9). Over time, these five hearths produced successive generations of urbanized world empires, followed by the diffusion of urbanization to the rest of the world.

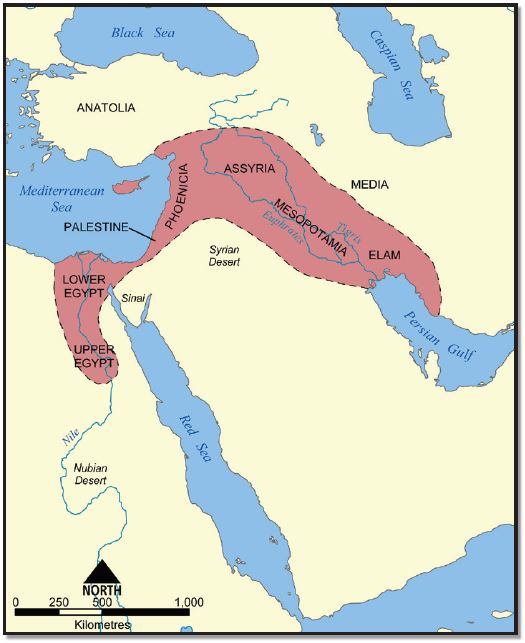

The first regions of independent urbanism were in Mesopotamia and Egypt from around 3500 B.C.E. Mesopotamia, the land between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, was the eastern part of the so-called Fertile Crescent (Figure 12.10). From the Mesopotamian Basin, the Fertile Crescent stretched in an arc across the northern part of the Syrian Desert as far west as Egypt, in the Nile Valley. In Mesopotamia, the significant growth in size of some of the agricultural villages formed the basis for the large fortified city-states of the Sumerian Empire such as Ur, Uruk, Eridu, and Erbil, in present-day Iraq. By 1885 B.C.E., the Sumerian city-states had been taken over by the Babylonians, who governed the region from Babylon, their capital city. Unlike in Mesopotamia, internal peace in Egypt determined no need for any defensive fortification. Around 3000 B.C.E. the largest Egyptian city was probably Memphis (over 30,000 inhabitants). Yet, between 2000 and 1400 B.C.E., urbanization continued with the founding of several capital cities such as Thebes and Tanis.

About 2500 B.C.E., large urban settlements were developed in the Indus Valley (Mohenjo-Daro, especially), in modern Pakistan, and later, about 1800 B.C.E., in the fertile plains of the Huang He River (or Yellow River) in Northern China, supported by the fertile soils and extensive irrigation systems. Other areas of independent urbanism include Mesoamerica (Zapotec and Mayan civilizations, in Mexico) from around 100 B.C.E. and, later, Andean America from around 800 C.E. (Inca Empire, from northern Ecuador to central Chile). Teotihuacan (Figure 12.11), near modern Mexico City, reached its height with about 200,000 inhabitants between 300 and 700 C.E.

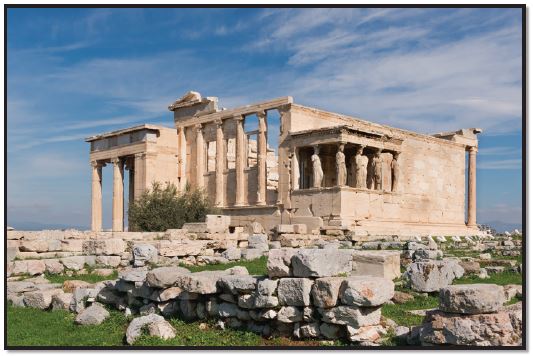

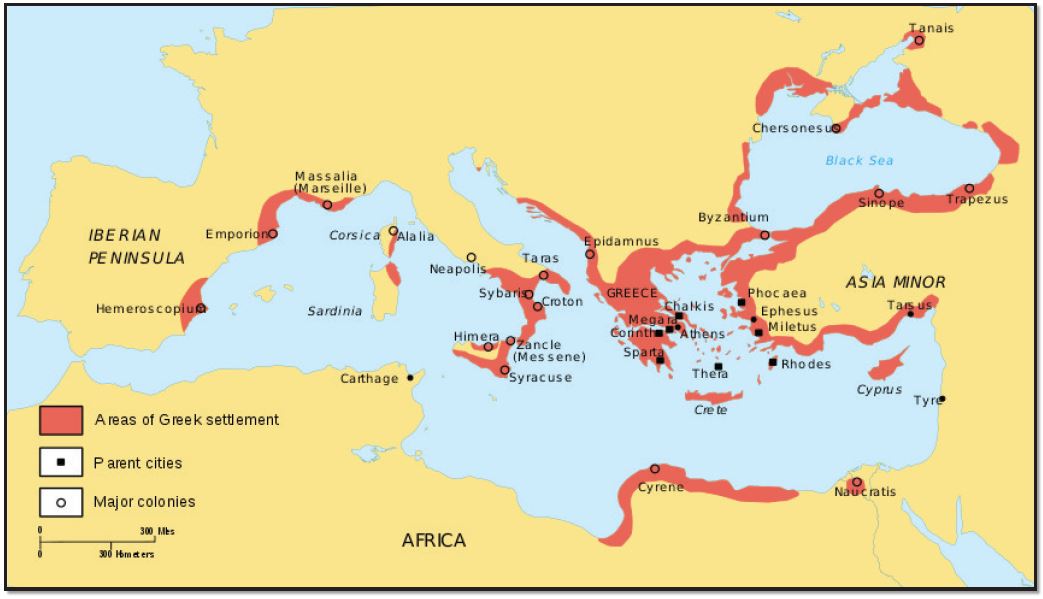

The city-building ideas eventually spread into the Mediterranean area from the Fertile Crescent. In Europe, the urban system was introduced by the Greeks, who, by 800 B.C.E., founded famous cities such as Athens, Sparta, and Corinth. The city’s center, the “acropolis” (Figure 12.12), was the defensive stronghold, surrounded by the “agora” suburbs, all surrounded by a defensive wall. Except for Athens, with approximately 150,000 inhabitants, the other Greek cities were quite small by today’s standards (10,000-15,000 inhabitants). The Greek urban system, through overseas colonization, stretched from the Aegean Sea to the Black Sea, around the Adriatic Sea, and continued to the west until Spain (Figure 12.13). Although the Macedonians conquered Greece during the 4th century B.C.E., Alexander the Great extended the Greek urban system eastward toward Central Asia. The location of the cities along Mediterranean coastlines reflects the importance of long-distance sea trade for this urban civilization.

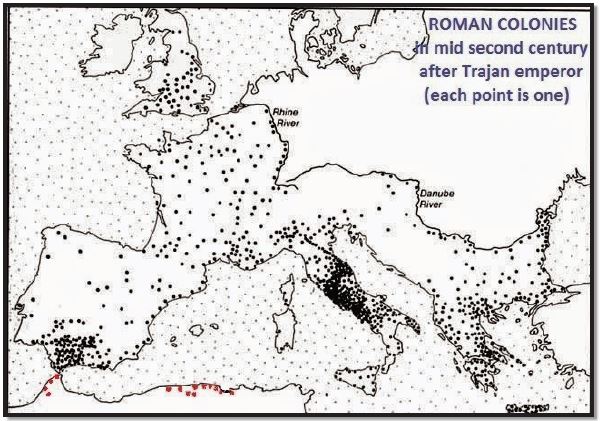

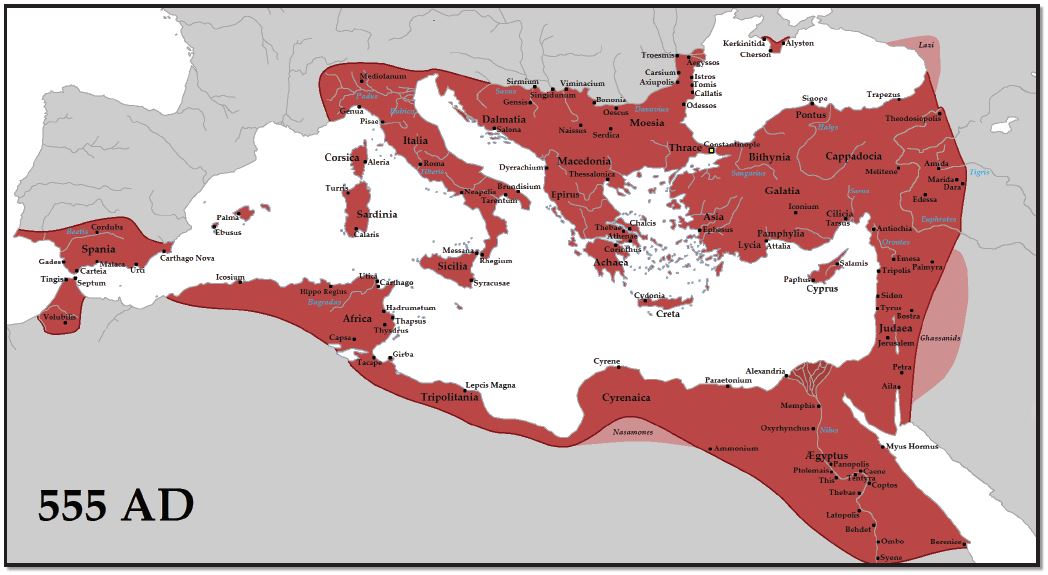

With the impressive feats of civil engineering, the Romans had extended towns across southern Europe (Figure 12.14), connected with a magnificent system of roads. Roman cities, many of them located inland, were based on the grid system. The center of the city, the “forum,” surrounded by a defensive wall, was designated for political and commercial activities. By 100 C.E., Rome reached approximately one million inhabitants, while most towns were small (2,000-5,000 inhabitants). Unlike Greek cities, Roman cities were not independent, functioning within a well-organized system centered on Rome. Moreover, the Romans had developed very sophisticated urban systems, containing paved streets, piped water, and sewage systems, and added massive monuments, grand public buildings (Figure 12.15), and impressive city walls. In the 5th century, when Rome declined, the urban system, stretching from England to Babylon, was a well-integrated urban system and transportation network, laying the foundation for the Western European urban system.

12.3.2 Dark Ages

Although urban life continued to flourish in some parts of the world (Middle East, North, and sub-Saharan Africa), Western Europe recorded a decline in urbanization after the collapse of the Roman Empire in the fifth century. During this early medieval period, 476-1000 C.E., also known as the Dark Ages, feudalism was a rurally oriented form of economic and social organization. Yet, under Muslim influence in Spain or under Byzantine control, urban life was still flourishing. As Rome was falling into decline, Constantine the Great moved the capital of the Roman Empire to Byzantium, renaming the city Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul, Turkey). With its strategic location for trade, between Europe and Asia, Constantinople became the world’s largest city, maintaining this status for most of the next 1000 years (Figure 12.16).

Most European regions, however, did have some small towns, most of which were either ecclesiastical or university centers (Cambridge, England, and Chartres, France), defensive strongholds (Rasnov, Romania), gateway towns (Bellinzona, Switzerland), or administrative centers (Cologne, Germany). The most important cities at the end of the first millennium were the seats of the world empires/kingdoms: the Islamic caliphates, the Byzantine Empire, the Chinese Empire, and the Indian kingdoms.

12.3.3 Urban Revival in Europe

From the 11th century onward, a more extensive money economy developed. The emerging regional specializations and trading patterns provided the foundations for a new phase of urbanization based on merchant capitalism. By 1400, long-distance trading was well established based not only on luxury goods but also on metals, timber, and a variety of agricultural goods. At that time, Europe had about 3000 cities, most of them very small. Paris, with about 275,000 people, was the dominant European city. Besides Constantinople (Byzantium) and Cordoba (Spain), only cities from northern Italy (Milan, Florence) and Bruges (Belgium) had more than 50,000 inhabitants.

Between the 14th and 18th centuries, fundamental changes occurred that transformed not only the cities and urban systems of Europe but also the entire world economy. Merchant capitalism increased in scale, and the Protestant Reformation and Scientific Revolution of the Renaissance stimulated economic and social reorganization. Overseas colonization allowed Europeans to shape the world’s economies and societies. Spanish and Portuguese colonists were the first to extend the European urban system to the world’s peripheral regions. Between 1520 and 1580 Spanish colonists established the basis of a Latin American urban system. Centralization of political power and the formation of national states during the Renaissance determined the development of more integrated national urban systems.

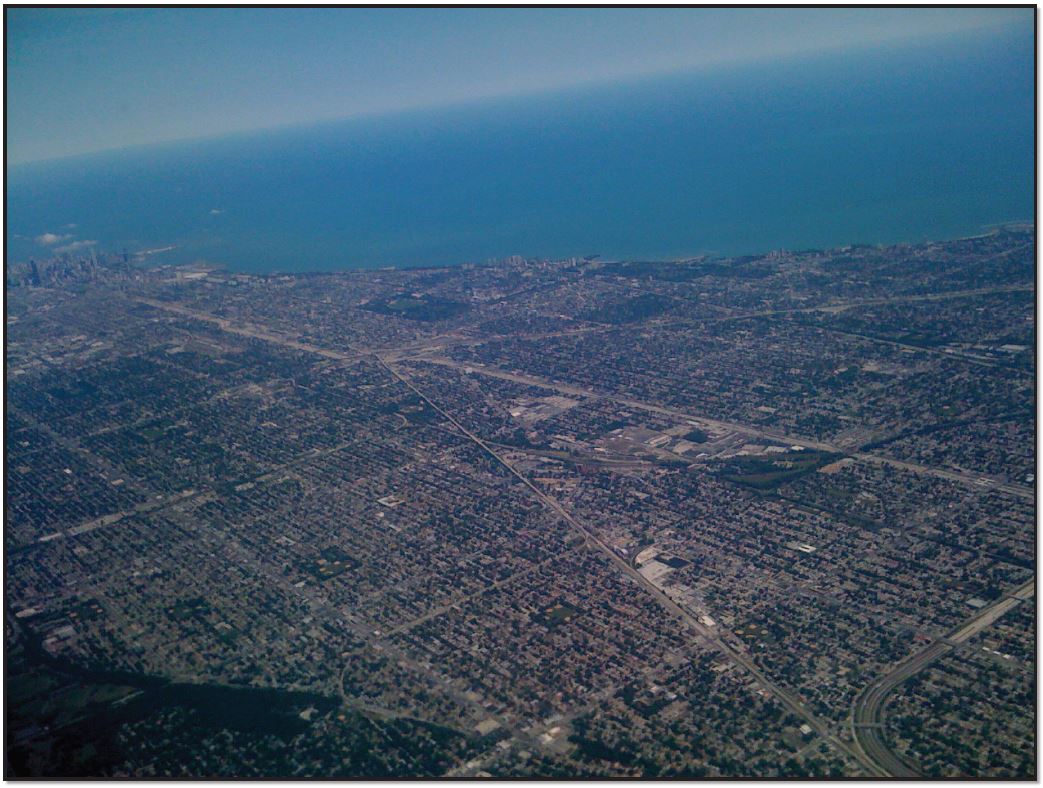

12.3.4 Industrial Revolution and Urbanization

Although the urbanization process had already progressed significantly by the 18th century, the Industrial Revolution was a powerful factor accelerating further urbanization, generating new kinds of cities, some of them recording an unprecedented concentration of population. Manchester, for example, was the shock city of European industrialization in the 19th century, growing from a small town of 15,000 inhabitants in 1750 to a world city by 1911 with 2.3 million. Industrialization spread from England to the rest of Europe during the first half of the 19th century and then to different parts of the world. Moreover, followed by successive innovations in transport technology, urbanization increased at a faster pace. The canals, railroads, and steam-powered transportation reoriented urbanization toward the interior of the countries. In North America, the shock city was Chicago, which grew from 4,200 inhabitants in 1837 to 3.3 million in 1930. Its growth as an industrial city followed especially the arrival of the railroads, which made the city a major transportation hub. In the 20th century, innovations significantly helped urban development. By the 19th century, urbanization had become an important dimension of the world system. The higher wages and greater opportunities in the cities (industry, services) transformed them into a significant pull factor, attracting a massive influx of rural workers. Consequently, the percentage of people living in cities increased from 3 percent in 1800 to 54 percent in 2017.4 In developed countries, 78 percent live in urban areas, compared with 49 percent in developing countries, reflecting the region’s and/or the country’s level of development.

12.3.5 City-Size Distribution

Most developed countries have a higher percentage of urban people, but developing countries have more very large urban settlements (Table 12.1, Figure 12.17). In 1950, out of the world’s 30 largest metropolitan areas, the first three metropolitan areas were in developed countries: New York (U.S.), Tokyo (Japan), and London (UK), two of which (New York and Tokyo) had more than 10 million inhabitants. After 30 years, in 1980, a significant change was recorded. Although metro New York increased from 12.3 million to 15.6 million, Tokyo, with 28.5 million inhabitants, became the largest metropolitan area in the world, a position which the city still maintains. In addition, except for Osaka, the second metropolitan area from Japan, two large metropolitan areas in developing countries were added, Mexico City (Mexico) and Sao Paulo (Brazil). The number of large metropolitan areas continued to increase after 2010, adding more developing countries such as India (Delhi and Mumbai/Bombay), China (Shanghai and Beijing), Bangladesh (Dhaka), and Pakistan (Karachi) from Asia and Egypt (Cairo), Nigeria (Lagos), and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (Kinshasa) from Africa. Each of these metropolitan areas is expected to have over 20 million inhabitants after 2020, adding Delhi and Shanghai to the largest metropolitan areas with over 30 million inhabitants. In the United States, New York-Newark is the largest metropolitan area, in which the population was constantly increasing from 12.3 million in 1950 to 15.6 million in 1980 and 18.3 million in 2010, having the potential to reach 20 million in 2030. Yet, unlike the developing countries, characterized by a very fast urban growth rate, the developed countries recorded a moderate urban growth rate.

| 1950 | 1980 | 2010 | 2025 |

|---|---|---|---|

| New York: 12.3 Tokyo: 11.2 Osaka: 9.0 London: 8.3 Mexico City: 3.1 Cairo: 2.5 Sao Paulo: 2.3 Delhi 1.4 |

Tokyo: 28.5 Osaka: 17.0 New York: 15.6 Mexico City: 13.3 Sao Paulo: 12.0 Cairo: 7.3 London: 6.8 Delhi: 5.6 |

Tokyo: 36.8 Delhi: 21.9 Mexico City: 20.1 Shanghai: 19.9 Sao Paulo: 19.6 Osaka: 19.4 Mumbai: 19.4 New York-Newark: 18.3 Cairo: 16.9 Beijing: 16.1 |

Tokyo: 37.04 Delhi: 34.67 Shanghai: 30.48 Dhaka: 24.65 Cairo: 23.07 Sao Paulo: 22.99 Mexico City: 22.75 Beijing: 22.59 Mumbai: 22.09 Osaka: 18.92 |

Table 12.1 Growth Across Major World Cities from 1950 – 2025 (footnote #5)

The relationship between the size of cities and their rank within an urban system is known as the rank-size rule, describing a regular pattern in which the nth-largest city in a country or region is 1/n the size of the largest city. According to the rank-size rule, the second-largest city is one-half the size of the largest, the third-largest city is one-third the size of the largest city, and so on. In the United States, the distribution of settlements closely follows the rank-size rule, but in other countries, the population of the largest city is disproportionately large about the second-and third-largest cities in that urban system. These cities are called primate cities (Buenos Aires, for example, is 10 times larger than Rosario, the second-largest city in Argentina). Yet, cities do not necessarily have to be primate to be functionally dominant (economic, political, cultural) within their urban system. The functional dominance of the city is called centrality. Moreover, some of the largest metropolises, closely integrated within the global economic system and playing key roles beyond their national boundaries, qualify as world cities. Today, because of the importance of their financial markets and associated business services, London, New York, and Tokyo dominate Europe, the Americas, and Asia, respectively.

12.4 URBAN PATTERNS

12.4.1 North American Cities

The contemporary North American scene dramatically displays how its population has refashioned the settlement landscape to meet the needs of a modern postindustrial society. In North American cities, a city’s center, commonly called downtown, has historically been the nucleus of commercial and services land use.

It is also known as the central business district (CBD), usually being one of the oldest districts in a city and the nodal point of transportation routes. The CBD gives visual expression to the growth and dynamic of the industrial city, becoming a symbol of progress, modernity, and affluence. It contains the densest and tallest nonresidential buildings, and its accessibility attracts a diversity of services.

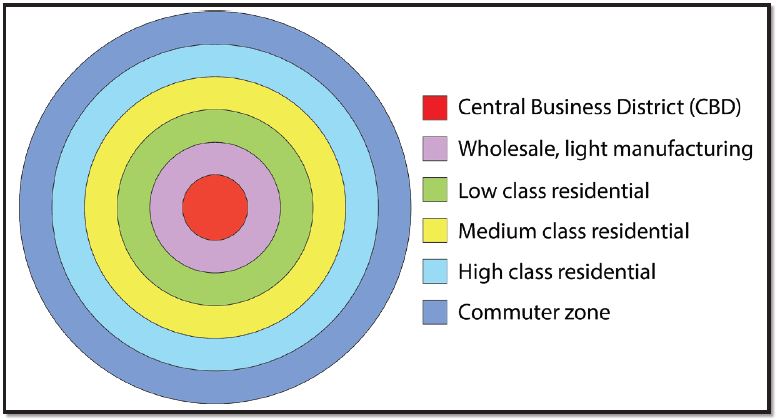

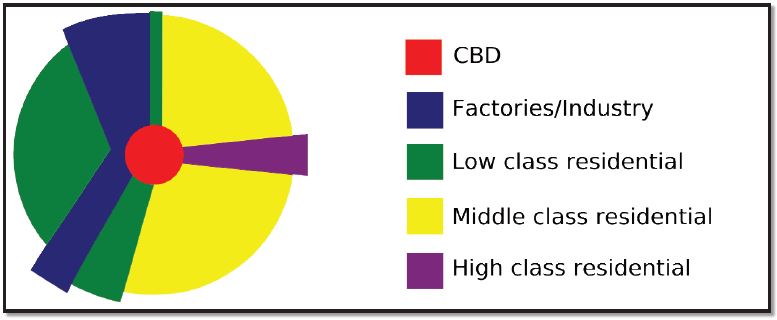

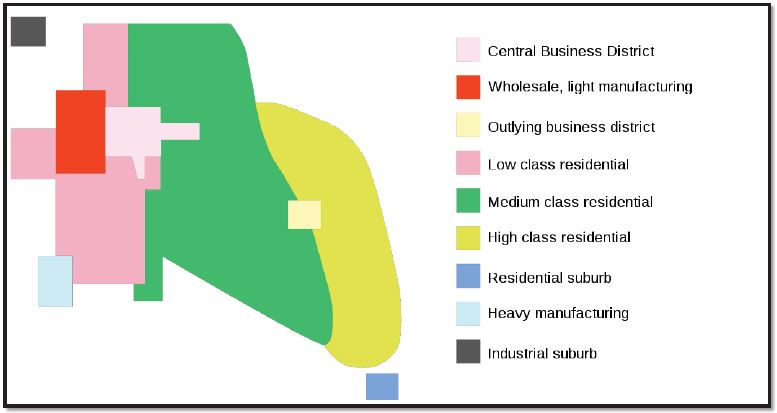

Urban decentralization also reconfigured land-use patterns in the city, producing today’s metropolitan areas. If during the first half of the 20th century, the concentric zone model was idealized, in which urban land is organized in rings around the CBD, today’s urban model highlights new suburban growth characterized by a mix of peripheral retailing, industrial areas, office complexes, and entertainment facilities called “edge cities.” In addition, the sector and multiple nuclei (multiple growth points) models of urban structure were developed to help explain where different socio-economic classes tend to live in an urban area (Figures 12.19, 12.20, and 12.21). All models show new residential districts added beyond the CBD as the city expanded, with higher-income groups seeking more desirable, peripheral locations.

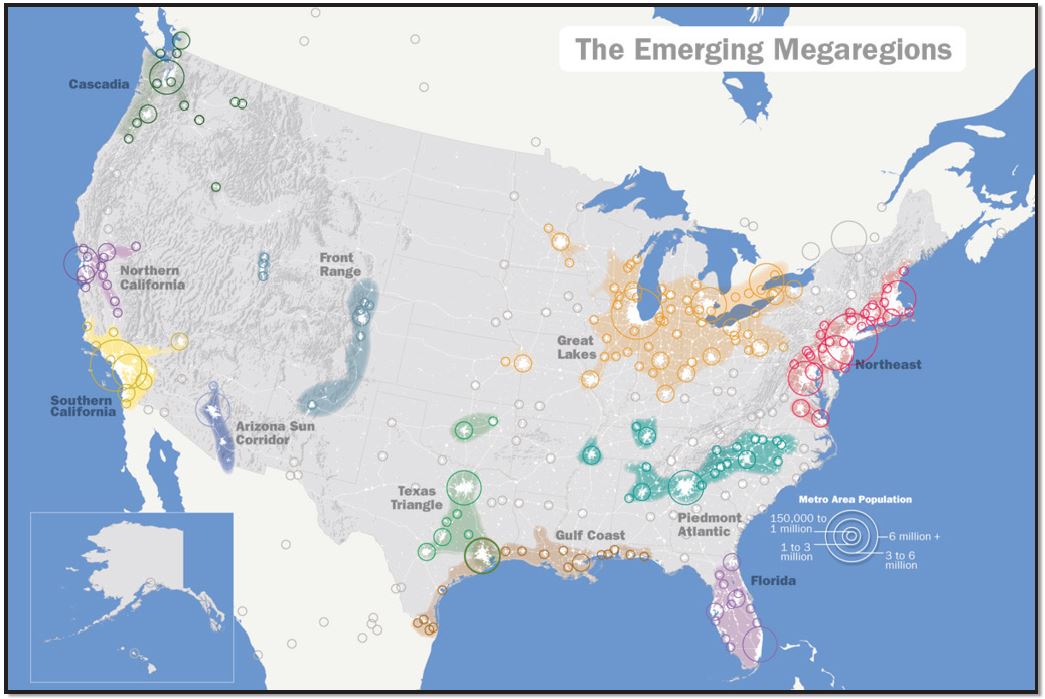

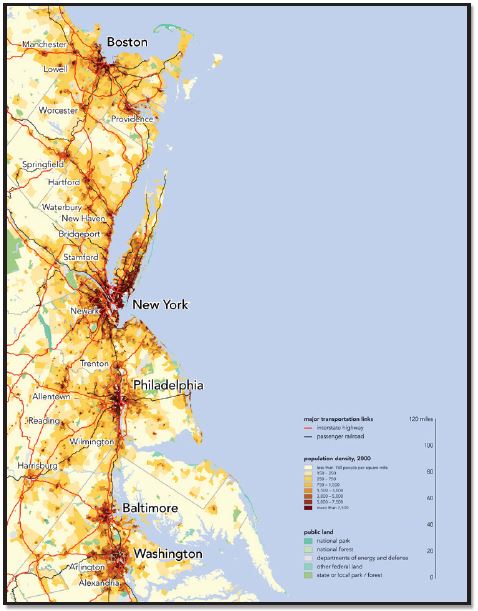

Metropolitan clusters produce uneven patterns of settlement across North America. Eleven urban agglomerations, also known as megalopolises, exist in the United States and Canada, 10 of them being located in the United States (Figure 12.22). Boston–Washington Corridor, or BosWash, with its roughly 50 million inhabitants, representing 15 percent of the U.S. population, is the most heavily urbanized region of the United States (Figure 12.23). The region, located on less than two percent of the nation’s land area, accounts for 20 percent of the U.S. GDP.

Like many other cities in the core regions, North American cities are also recognized for their prosperity. Yet, some problems still exist such as fiscal squeeze (less money from taxes), poverty, homelessness, neighborhood decay, and infrastructure needs. By contrast, some inner cities experience the process of gentrification, invaded by higher-income people who work downtown and who are seeking the convenience of less expensive and centrally located houses. Many gentrified properties have attractive architectural details and are larger than centrally located apartments.

12.4.2 European Cities

One characteristic of Europe is its high level of urbanization. Even in sparsely settled Northern Europe, over 80 percent of the people live in urban areas (Iceland 94 percent)7.

Southern and Eastern Europe are the least urbanized, with an average of 69-70 percent. While widespread urbanization is relatively recent in Europe, dating back only a century or two, the spread of cities into Europe can be associated with the classical Greek and Roman Empires, making many cities in Europe more than 2,000 years old. Among the largest metropolitan areas are Paris (10.9 mill.), London (10.4 mill.), and Madrid (6.1 mill.)8. European cities, like North American cities, reflect the operation of competitive land markets, and they also suffer from similar problems of urban management, infrastructure maintenance, and poverty. Yet, what makes most European cities distinctive in comparison with North American cities is their long history, being the product of several major epochs of urban development.

The three-zone models (concentric, sector, and multiple nuclei) characterizing North American urban areas are also valid in Europe, but there are significant differences regarding the spatial distribution of social groups, who may not have the same reasons for selecting particular neighborhoods within their cities. The European Central Business Districts (CBDs), for example, are inhabited by more residents than CBDs of the United States, most of them being higher-income people attracted by the opportunities to have access to commercial and cultural facilities, as well as to occupy beautiful old buildings located in some elegant residential districts. As a result, European CBDs are less dominated by business services than American CBDs. CBDs are, in general, very expensive in urban areas. Consequently, poor people are more likely to live in outer rings in European cities.

Because many of today’s most important European cities were founded in the Roman and medieval periods, there are strict rules for the preservation of their historic CBDs, such as banning motor vehicles; maintaining low-rise structures, plazas, squares, and narrow streets; and preserving the original architecture, including the former cities’ walls. Impressive palaces, cathedrals, churches, and monasteries, accompanied by a rich variety of symbolism—memorials and statues—also constitute the legacy of a long and varied history (Figure 12.24).

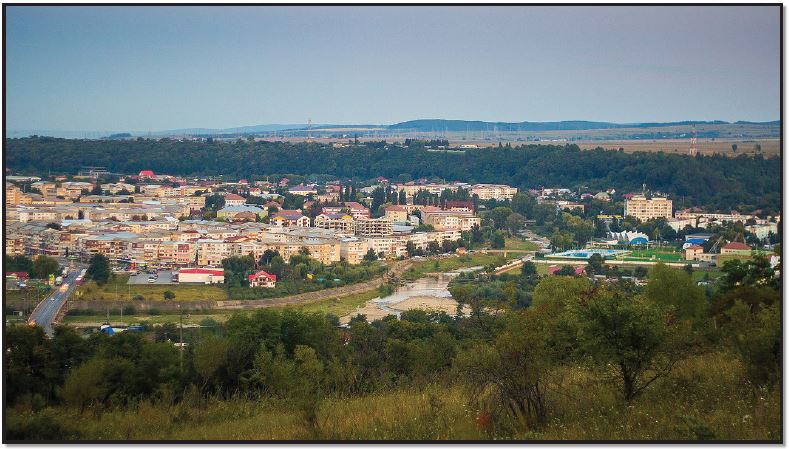

The diversity of Europe’s geography means that there are important variations not only from the Germanic cities to the cities of Mediterranean Europe but also from these areas to the eastern European cities, which experienced over 40 years of communism. State control of land and housing determined the development of a specific pattern of land use, expressed by huge public housing estates and industrial zones. In some cases, the structure of the old cities has been altered, and the new urban development has extended over rural areas (Figure 12.25).

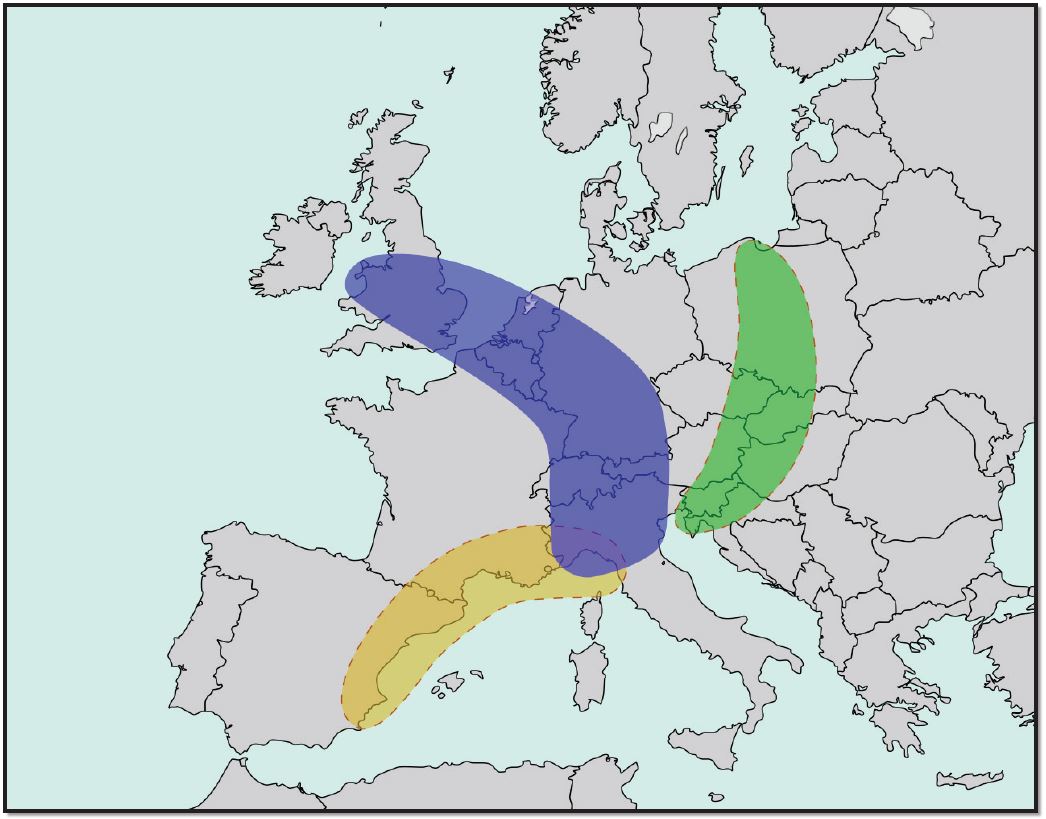

Europe has overlapping metropolitan areas. The most extensive megalopolis, Blue Banana, also known as the Manchester-Milan Axis, is a discontinuous urban corridor in Western Europe, with a population of around 111 million inhabitants. It stretches approximately from North West England across Greater London to the Benelux states and along the German Rhineland, Southern Germany, Alsace in France in the west, and Switzerland to Northern Italy in the south (Figure 12.26). New regions that have been compared to the Blue Banana can be found on the Mediterranean coast between Valencia and Genoa, as part of the Golden Banana or European Sunbelt, and in the north of Germany, where another conurbation lies on the North Sea coast, stretching into Denmark, and from there into southern Scandinavia.

12.4.3 Suburban Sprawl versus Sustainable Cities

12.4.3.1 Suburban Sprawl

The growth in automobile ownership in the U.S., the new infrastructure systems, and the long-term home financing, as well as the tremendous amount of annexations of territory from surrounding counties, resulted in a dramatic spurt in suburban growth (Figure 12.27). Thus, sprawl is endemic to North American urbanization. Low-density and single-family suburban development is a positive aspect of suburbanization. Today, about 50 percent of Americans live in suburbs. Sprawl is less common outside European cities. Yet, the personal and environmental costs of this development are also significant. Noteworthy among these are automobile dependence, increased commute time, and the cost of gasoline, as well as air pollution and health problems. Even worse, more and more agricultural land is lost in favor of residential developments. Equally important, local governments must spend more money than is collected through taxes to provide services to the suburban areas.

12.4.3.2 Sustainable Cities

The compromise solution is “smart growth,” known as “compact city” in Europe, particularly in the United Kingdom. Smart growth is urban planning that concentrates growth in compact areas, strategically designed with adequate infrastructure and walkable, transit-oriented, bicycle-friendly urban centers. Characteristics of smart development include higher density living spaces; preserving open space, farmland, and natural and cultural resources; providing a variety of transportation choices; making development decisions predictable, fair, and cost-effective; equitably distributing the costs and benefits of development; and encouraging community collaboration in developing decisions. Smart growth and related concepts are not necessarily new but are a response to car culture and sprawl. Smart growth values long-range, regional considerations of sustainability over a short-term focus. Yet, in practice, the process experiences challenges even from citizens, in some cases expressing their opposition to the local smart growth projects.

12.5 SUMMARY

In summary, definitions of the terms rural and/or rurality and delineation of rural from urban areas have been long-debated topics in many academic works. Rural space comes into existence in certain areas, typified by a series of factors such as land use (especially for agriculture), population density, agricultural employment, and built areas. Generally, rural areas are considered to be synonymous with more extensive land use activities in agriculture and forestry, low population density, small settlements, and an agrarian way of life. Rural space is divided into territorial entities, with variable scales, covering the local or regional economy, and each unit includes both agricultural and non-agricultural activities. Different countries have varying definitions of rural for statistical and administrative purposes. Although urbanization is a global phenomenon, today about 43 percent of the world’s population still lives in rural areas.9

There are many types of rural settlements. Early villages had to be near a reliable water supply, be defensible, and have sufficient land nearby for cultivation, to name but a few concerns. They also had to adapt to local physical and environmental conditions, conditions that can be identified with a practiced eye. Villages in the Netherlands are linear, crowded on the dikes surrounding land reclaimed from the sea. Circular villages in parts of Africa indicate a need for a haven for livestock at night. A careful examination of the rural settlement of a region reveals much about its culture, history, and traditions.

Most people can agree that cities are places where large numbers of people live and work and are hubs of government, commerce, and transportation. But how best to define the geographical limits of a city is a matter of some debate. So far, no standardized international criteria exist for determining the boundaries of a city. Often, different boundary definitions are available for any given city. The “city proper,” for example, describes a city according to an administrative boundary, while “urban agglomeration” considers the extent of the built-up area to delineate the city’s boundaries. A third concept of the city, the “metropolitan area,” defines its boundaries according to the degree of economic and social interconnectedness of nearby areas.

The United Nations, the most comprehensive source of statistics regarding urbanization, emphasizes the fact that more than one-half of the world population now lives in urban areas (57 percent in 2023),10 and virtually all countries of the world are becoming increasingly urbanized. Yet, given the fact that different countries use different definitions, it is difficult to know exactly how urbanized the world has become. Canada and Australia consider urban settlements to have 1,000 inhabitants or more, for example, while a settlement of 2,000 is a significant urban center in Peru. Other countries consider other limits for urban settlements such as 5,000 inhabitants in Romania and 50,000 in Japan. Consequently, in 2016, the percentage of urban population by continent was as follows: North America, 83 percent, the most urbanized continent in the world; Latin America, 81 percent; Europe, 75 percent; Oceania, 67 percent; Asia, 52 percent; and Africa, 44 percent.11

12.6 KEY TERMS DEFINED

Annexation – legally adding land area to a city

Blue Banana – a discontinuous corridor of urbanization in Western Europe, from North West England to Northern Italy

BosWash – the United States megalopolis, extending from Boston to Washington D.C.

Central business district (CBD) – the central nucleus of commercial land uses in a city

Centrality – the functional dominance of cities within an urban system

City-state – a sovereign state that consists of a city and its dependent territories

Clustered rural settlement – an agricultural-based community in which a number of families live in close proximity to each other, with fields surrounding the collection of houses and farm buildings

Concentric zone model – a model of the internal structure of cities in which social groups are spatially arranged in a series of rings

City – an urban settlement that has been legally incorporated into an independent, self-government unit

Dark Ages – early medieval period, 476-1000 C.E.

Dispersed rural settlement – a rural settlement pattern in which farmers live on individual farms isolated from neighbors

Dualism – the juxtaposition in geographic space of the formal and informal sectors of the economy

Edge city – a nodal concentration of shopping and office space situated on the outer fringes of metropolitan areas, typically near major highway intersections

Fiscal squeeze – increasing limitations on city revenues, combined with increasing demands for expenditure

Fordism – principles for mass production based on assembly-line techniques, scientific management, mass consumption based on higher wages, and sophisticated advertising techniques

Gateway City – serves as a link between one country or region and others because of its physical situation

Gentrification – an invasion of older, centrally located, working-class neighborhoods by higher-income households seeking the character and convenience of less expensive and well-located residences

Hearth areas – the locations of the five earliest urban civilizations

Informal sector – economic activities that take place beyond official record, not subject to formalized systems of regulation or remuneration

Iraal – a traditional African village of huts, typically enclosed

Megacity – a very large city characterized by both primacy and high centrality within its national economy

Megalopolis (megapolitan region) – a continuous urban complex (the chain of metropolitan areas) along a specific area (a clustered network of cities)

Merchant capitalism – the earliest phase in the development of capitalism as an economic and social system

Multiple-nuclei model – a model of the internal structure of cities in which social groups are arranged around a collection of nodes of activities

Neo-Fordism – economic principles in which the logic of mass production coupled with mass consumption is modified by the addition of more flexible production, distribution, and marketing systems

Primacy – a condition in which the population of the largest city in an urban system is disproportionately large in relation to the second-and third-largest cities

Primate city – the largest settlement in a country, if it has more than twice as many people as the second-ranking settlement

Protestant Reformation – a schism from the Roman Catholic Church initiated by Martin Luther

Rank-size rule – statistical regularity in the size distribution of cities and regions

Renaissance – a period in European history, from the 14th to the 17th century, regarded as the cultural bridge between the Middle Ages and modern history

Reurbanization – growth of population in metropolitan central cores, following a period of absolute or relative decline in population

Scientific Revolution – a concept used by historians to describe the emergence of modern science during the early modern period

Sector model – a model of the internal structure of cities in which social groups are arranged around a series of sectors, radiating out from the central business district

Shock city – a city recording surprising and disturbing changes in economic, social, and cultural life in a short period

Sprawl – development of new housing sites at relatively low density and at locations that are not contiguous to the existing built-up area

Suburbanization – growth of population along the fringes of large metropolitan areas

Underemployment – a situation in which people work less than full-time even though they would prefer to work more hours

Urban area – a dense core of census tracts, densely settled suburbs, and low-density land that links the dense suburbs with the core

Urban forms – physical structure and organization of cities

Urban system – an interdependent set of urban settlements within a specified region

Urbanism – way of life, attitudes, values, and patterns of behavior fostered by urban settings

Urbanization – increasing concentration of population into growing metropolitan areas

World city – a city in which a disproportionate part of the world’s most important business is conducted

World empire – mini-systems that have been absorbed into a common political system while retaining their fundamental cultural differences

Zone in transition – an area of mixed commercial and residential land uses surrounding the CBD

12.6 WORKS CONSULTED AND FURTHER READING

Berkovitz, P. and Schulz-Greve, W. 2001. Defining the concept of rural development: A European perspective. In The Challenge of Rural Development in the EU Accession Countries. Third World Bank/FAO EU Accession Workshop, Sofia, Bulgaria, June 17-20, 2000, ed. C. Csaki and Z. Lerman, 3-9. Washington, D. C.: The World Bank

____. Blue Banana. [Online]. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Blue_Banana

____. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Blue_Banana#/media/File:Blue_Banana.svg

Cadwallader, M. 1996. Urban geography: An analytical approach. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall

Central Intelligence Service. https://www.cia.gov/index.html

____. The Circular Villages of the Wendland region. http://www.germany.travel/

____. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_cities_in_the_Americas_by_year_of_foundation

____. https://www.google.com/search?q=compact+village+maps&tbm=isch&tbo=u&sourc/

____. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Compact_city

____. https://www.google.com/search?q=Indian+compact+villages+photos

Dickenson, J., Gould, B., Clarke, C., Marther, S., Siddle, D., Smith, C., and Thomas-Hope, E. 1996. A Geography of the Third World. Second edition. New York: Routledge

____. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dispersed_settlement

____. https://www.google.com/search?q=Erbil+Iraq+photos

Green, R. and Pick, J. 2006. Exploring the Urban Community: A GIS Approach. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall

Johnston, R. J., Gregory, D., Pratt, G. and Watts, M. 2003. The Dictionary of Human Geography. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing

Knox, P. and McCarty, L. 2005. Urbanization: An Introduction to Urban Geography. Second Edition. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall

Knox, P. and Marston, S. 2010. Human Geography: Places and Regions in Global Context. Fifth Edition. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson

Knox, P. and Marston, S. 2013. Human Geography: Places and Regions in Global Context. Sixth Edition. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson

____. Kraal. [Online]. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kraal

____. https://www.google.com/search?q=circular+villages+in+Africa+Kraal

Levis, K. Rural settlement patterns. https://louis.pressbooks.pub/humangeography/chapter/12human-settlements/

____. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Linear_settlement

____. https://www.historicplaces.ca/en/rep-reg/image-image.aspx?id=13161#i1

Marston, S., Knox, P., Liverman, D., Del Casino, V., and Robbins, P. 2017. World Regions in Global Context: People, Places, and Environments. Sixth Edition. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson

Means, B. K. 2007. Circular villages of the Monongahela tradition. [Online]. https://muse.jhu.edu/pub/181/monograph/book/6649

____. http://www.ancientmesopotamians.com/cities-in-mesopotamia.html

____. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Megalopolis_Northeast_Megalopolis

Population Reference Bureau. 2016 World population data sheet. [Online]. https://www.prb.org/resources/2016-world-population-data-sheet/

Pulsipher, L. 2000. World Regional Geography. New York. W. H. Freeman and Company

____. Romania: Settlement patterns. Encyclopaedia Britannica. [Online]. https://www.britannica.com/place/Romania/Settlement.patterns

Rowntree, L., Lewis, M., Price, M., and Wyckoff, W. 2006. Diversity amid globalization: World regions, environment, development. Third Edition. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall

Rubenstein, J. 2013. Contemporary Human Geography. 2e. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson

Rubenstein, J. 2016. Contemporary Human Geography. 3e. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson

____. Rundling. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rundling

____. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/smart-growth

____. https://www.google.com/serach!q+Spanish_and_Portuguese_Empires

Todaro, M. 2000. Economic Development. Seven Edition. New York: Addison-Wesley

United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. World Urbanization Prospects: The 2011 revision. File 11a: The 30 Largest urban agglomerations ranked by population size at each point in time, 1950–2025. [Online]. http://esa.un.org/unpd/wup/CD-ROM_2011/WU

United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. World Urbanization Prospects: The 2014 revision. File 11a: The 30 Largest urban agglomerations ranked by population size at each point in time, 1950–2030. https://esa.un.org/unpd/wup/Publications/Files/WUP2014-Report.pdf

United Nations. The World’s Cities in 2016. http://www.un.org.en/development/desa/population/publications/pdf/urbanization/world-cities-in-2016_data_booklet.pdf/

____. Degree of Urbanization (Percentage of Urban Population in Total Population) by Continent in 2016. [Online]. https://www.statista.com/statistics/270860/urbanization-by-continent

____. http://www.google.com/search?q=urbanization+world_maps

World Bank. World Development Indicators: Urbanization. http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.URB.TOTL.IN.ZS

12.7 ENDNOTES

- https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=25806451. Accessed June 1, 2023.

- Population Reference Bureau. 2023 World Population Data Sheet. https://2023-wpds.prb.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/2023-World-Population-Data-Sheet-Booklet.pdf

- Adapted from http://www.3dgeography.co.uk/settlement-patterns

- Population Reference Bureau. www.prb.org. Accessed May 12, 2018.

- Adapted from United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. World Urbanization Prospects: The 2014 Revision. File 11a: The 30 Largest Urban Agglomeration Ranked by Population Size at each point in time, 1950–2030. http://esa.un.org/unpd/wup/CD-ROM_2014/WU, and World Population Review, Largest Cities by Population 2025.

- Adapted from https://urbandesigntheory.wordpress.com/2014/12/31/the-social- and-spatial-structure-of-urban-and-regional-systems/

- www.prb.org/pdf16/prb-wpds2016-web-2016.pdf. Accessed June 10, 2017.

- https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/resources/the-world-factbook/. Accessed 10 June 2017.

- Population Reference Bureau. www.prb.org. Accessed Dec 1, 2023.

- Population Reference Bureau. www.prb.org. Accessed Dec 1, 2023.

- https://www.statista.com/statistics/270860/urbanization-by-continent. Accessed Dec 1, 2023.