Chapter 4: Folk Culture and Popular Culture

Dominica Ramírez; David Dorrell; and Juana Ibáñez

This is the intersection of two iconic cultural symbols. Both the bus and the pilgrimage route invite the public to take journeys, whether sonic or geographic.

STUDENT LEARNING OUTCOMES

By the end of this section, the student will be able to:

- Understand: the origins and diffusion of culture and globalization

- Explain: how culture changes across space and time

- Describe: popular and folk culture, diffusion, and the changing pace of globalization

- Connect: globalization and cultural conflict

CHAPTER OUTLINE

- 4.1 Introduction

- 4.2 The Cultural Landscape

- 4.3 Folk Culture

- 4.4 The Changing Cultural Landscape

- 4.5 Popular Culture

- 4.6 The Interface Between the Local and the Global

- 4.7 Global Culture

- 4.8 Resistance to Popular Culture

- 4.9 Summary

- 4.10 Key Terms Defined

- 4.11 Works Consulted and Further Reading

- 4.12 Endnotes

4.1 INTRODUCTION

What is culture? Culture is learned behavior. Humans teach it to one another through mimicry or lessons. Humans learn behavior to meet their basic needs for food, water, air, shelter, and companionship. How we manifest those behaviors is expressed differently depending on where we live. How you relate to the rest of the world can be considered your “culture.” One benefit of this learned behavior is that it can help answer questions. Some of the questions that are answered are philosophical or ideological—for example, “Where did we come from?” or “What is acceptable behavior?” Other questions revolve around daily life: “How do we secure shelter, clothe ourselves, produce food, and transmit information?” Culture provides us with guidance for our lives. It both asks and answers questions. Children, from an early age, start asking “What is my place in the world?” Culture helps to answer that.

The word culture itself comes from the Latin word cultura, meaning cultivation or growing. This is precisely what humans do with both their material and abstract cultural components. Humans, since early childhood, learn to shape, create, share, and change their culture. Culture is the very vehicle we use to navigate through our environments. Culture is a form of communication, and it evolves. And as a type of compass, it leads.

4.1.1 Components of Culture

At the most simplistic levels, culture can be either concrete and tangible (material culture) or abstract (nonmaterial culture). Culture is a human construct used as a way to create a sense of belonging. Material culture is recognized through its artifacts (goods or technology). Nonmaterial culture includes mentifacts (ideas or beliefs) and sociofacts (forms of social organization). People convey culture through various outlets such as festivals, language, religion, food, and architecture. With culture, people are taught to meet their basic needs while maintaining individual group qualities.

All cultures have underlying beliefs and thought processes. These beliefs include religion (Chapter 6) and language (Chapter 5) but go far beyond that. Other important beliefs include things like nationalism (see Chapter 8), customs, or prejudices. These beliefs can be expressed through various avenues, using a variety of auditory, visual, and tactile means. For example, nationalism can be expressed through song, cuisine, dress, and public events. You can hear nationalism in the form of an anthem, see it in the form of a flag, taste it when you eat a dish that represents a group of people, and feel it in the form of a piece of jewelry.

Technology is a human construct. From our earliest inventions (fire and weapons) to a supercomputer, the things that people build are products of their perceived needs, their technical abilities, and their available resources. Technology includes clothing, food, and housing. Technology is material culture. Think of material culture as the material that archaeologists study. The materials that we use are often left behind for later people to study, like the clay tablets the Sumerians used to record their writing or Native American earthen mounds, such as Poverty Point, built up along riverways. Other components of culture (nonmaterial culture like ideas) leave fewer traces. We can find material culture related to burial practices that date back millennia but may not always have the material evidence to show how people grieve.

Lifestyle is a component of culture that can be overlooked, but it is vitally important. In many cultures, a family is a very large unit, and people can tell in great detail their exact relationship to everyone else in a place. In the modern context, a family could consist of a single parent and a child, and it is possible to live in a neighborhood filled with unrelated people and not know the name of a single neighbor.

Culture can be seen either through the lens of a microscope or through that of a telescope. Folk culture is local, small, and tightly bound to the immediate landscape. Popular culture (also called "pop" culture) is large, dispersed, and globalizing. These two forms of culture are not separated. They are related and both currently exist in the world. Before about 2008, most people on Earth lived in rural communities, often practicing a folk culture. The world as a whole is moving toward popular culture.

4.1.2 Cultural Reproduction

As human beings, we reproduce in two ways: biologically and socially. Physically we reproduce ourselves through having children. Social behavior reproduction or cultural reproduction consists solely of learned behavior. For culture to reproduce itself, it has to be taught. This is what makes culture a human creation. How is culture transmitted? Human beings are natural mimics. This is the way we learn to speak, and it is the way we learn the rest of our culture as well. We learn through observation and, subsequently, through practice. On another scale, mimicry is the mechanism that drives cultural diffusion. Human beings copy the things we like. The old line “Imitation is the sincerest form of flattery” perfectly describes the human desire to incorporate successful adaptations.

How people have shared culture has changed drastically over time. This can partly be attributed to the channels in which we share culture. In the past, culture was shared orally and in person. Words eventually became written, the written became electronic, and we now have access to things from anywhere at any time.

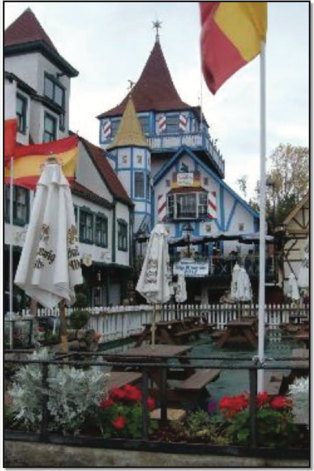

The debate over authenticity has also become a topic of debate. If culture is created, recreated, and fluid, how can we define authenticity? Has culture become placeless? Placelessness or the irrelevance of place has become a central topic in the contemporary philosophy of geography. Can people have an All-American dining experience in the heart of Madrid, Spain? Can they experience Spanish street food at a historic theme park in Copenhagen, Denmark? As Figures 4.2 and 4.3 show, icons representing other places are now common in the landscape.

This restaurant is near one of the busiest tourist areas in the city, but it is on a side street off the iconic Gran Vía. Could you imagine this restaurant on a street corner in the United States?

Notice the use of yellow and red (the colors of the Spanish flag).Also, the bull and matador image is prominent. Is that the best way to promote churros, a typical fried food of Spain?

4.1.3 Culture Hearths

Human beings have always had "learned" behaviors; it is one of the defining characteristics of human beings. Cultural evolution describes the increasing complexity of human societies over time. Our earliest cultures were simple. We lived in small groups, ranged across fairly large areas, and lived off the natural landscape. Human impact on the environment is less than it is now, but there was an impact. Earlier peoples burned forests to clear land and flush game and, in some places, hunted the megafauna to extinction.

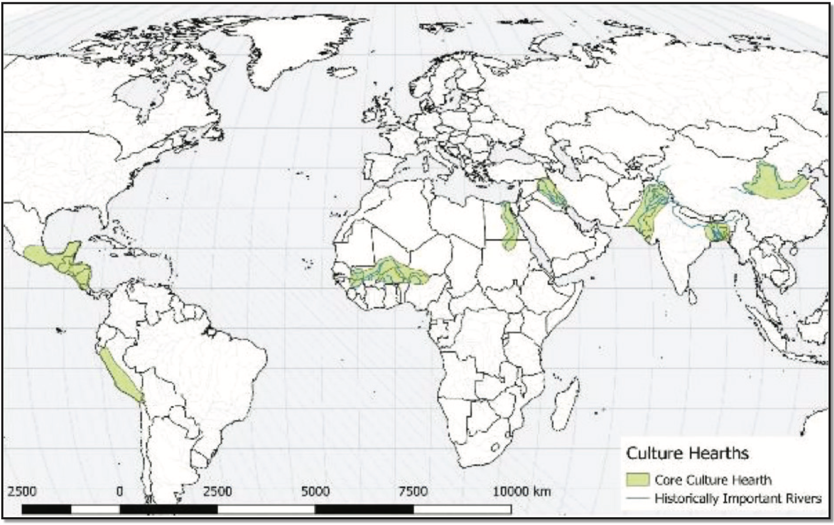

Recognizable cultures have places of origin. The word culture refers to cultivation, or growing. We care for something; we nurture an idea as it grows. All cultural elements have a place of origin. Some places have been responsible for a great deal of cultural development. We call these places culture hearths. Culture hearths provided many of the cultural elements (technologies, organizational structures, and ideologies) that would diffuse to other places and later times. Cultural hearths provide operational scripts for societies.

The oldest known culture hearths are closely associated with the foods that they domesticated. Domestication refers to the reproduction of food resources due to continued human intervention. Without the interference of humans in the food reproductive cycle, the food would not stay the same. Corn is a typical domesticated crop. Each of those kernels on the ear of corn is a seed. Humans are needed to break them off the cob to allow for the planting of those seeds to successfully grow. If the ears of corn were left untended and fell to the ground, the germination of all those seeds would result in not enough nutrients for the multitude of corn stalks in that spot, and so no corn would grow. Animals represent food sources, too. Breeds of animals are domesticated for an attribute that humans need—more milk, more meat, more drought resistance, etc. If those animals did not have humans isolating them during mating season, those animals would not necessarily mate with another of their same breed type; they would mate with another of the same species, which could change the productivity of the breed. Thus, nonwild food is an important cultural element because it is both a technology and a form of expression of what cultures consider important for sustenance.

Although Figure 4.4 shows areas of ancient civilization, these are not the only places that have contributed to contemporary cultures. Ideas can arise anywhere, but the beginnings of civilization, as we know it today, started in those ancient places thanks to the domestication of food sources. Cultures incorporate pieces of other cultures. Some recognizable themes in creation myths are stories of great floods or other cataclysmic events, and these types of stories are recycled through history. Languages without writing will often reuse another language’s writing system. Once again, desirable characteristics get copied or diffused through cultures.

4.2 THE CULTURAL LANDSCAPE

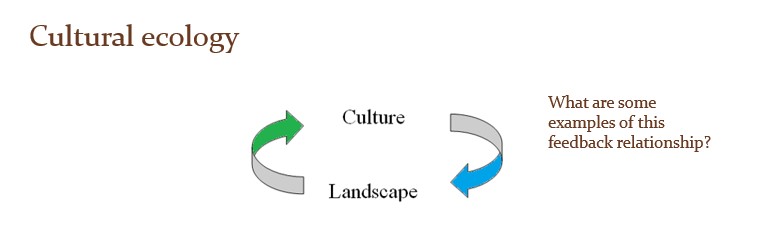

Cultures rely on natural resources to survive. In the case of rural cultures, those resources tend to be local. For urban cultures, those resources can either be local or products brought from great distances. Either way, cultures influence landscapes, and in turn landscapes influence cultures.

The physical landscape consists of places like the Appalachian Mountains that stretch across a large portion of North America, the Mongolian-Manchurian grasslands, the Amazon river basin, or any other environment. These are landscapes that have been formed over thousands, if not millions, of years by forces of nature. To live in places as different as these, humans have needed to adapt their lifestyles. The relationship between people, their culture, and the physical landscape is known as human-environment interaction or cultural ecology. This relationship is continually interacting and so always changing. Culture adapts to a particular place, and the adaptations change that physical environment. The physical systems that are changed adjust accordingly, and people must readapt to the changes (Figure 4.5). That process can be slow or fast.

Consider the reaction of communities after a climate disaster. New Orleanians rebuilt their homes in 2005 after Hurricane Katrina caused catastrophic failure of the levees that protected them. Some homes were rebuilt higher off the ground to potentially avoid future floods. Levees were rebuilt higher and stronger. Those changes to the landscape will cause more subsidence in the physical landscape in the long run because of the weight of the newer materials. Those resources to rebuild had to be gathered from locations where the physical environment was now altered. Culture determines what we can and cannot do to the people and the physical world around us. Those interactions never stop.

Humans have been thinking about the relationship between people and their environments for a considerable amount of recorded history. In the book On Airs, Waters, and Places, the Greek philosopher Hippocrates wrote that different climates produced different kinds of people. He believed that cold places produced emotionally distant people, and hot climates produced lazy, lethargic people. The ideal place (which coincidentally was his place) was in the middle of the known world and produced the best kind of people. These ideas would now be considered environmentally deterministic. Remember that environmental determinism is the idea that a particular landscape necessarily produces a certain kind of people. Ideas like this were still fashionable into the twentieth century. The problem with the idea is that it is simplistic and reductionist. A cold environment doesn’t force people to be aloof. It forces them to invent warmer clothes. Technology is the difference, not behavior. Instead of determinism, the more common term to use is now possibilism. Physical landscapes set limits on a group of people that may or may not require a large adaptation, or a large modification of the environment itself. Humans can now survive in very inhospitable environments, most notably the International Space Station.

Landscapes are cultural byproducts. The way that we use the local resources generates the visible landscape. Architecture, economic activities, clothing, and entertainment are all visible to anyone interested in looking at a place. Because the physical landscape varies across space, and because culture varies across space, then the cultural landscape is variable as well. Different people can have different adaptations to similar places. Conversely, places far from one another may have similar adaptations to climate or other factors.

Cultural landscapes can be considered as both history and narrative. Power is written into the landscape. We make statues to commemorate the wealthy and the politically connected in rich places. We place garbage dumps and airports in poor places. Looking at the landscape as a record of history, power, and representation is known as landscape-as-text. The landscape can be read in the same way that a book can be read. (See Figure 4.6.)

What is the narrative here? How have people changed/adapted the mountainous landscape of this region of Georgia, USA, to look like a town in mountainous Bavaria, Germany?

The largest differences between landscapes that we see now are the differences between the rural and the industrial and between places that are less integrated with the rest of the world and those that are heavily integrated (globalized). Global places are becoming homogenized.

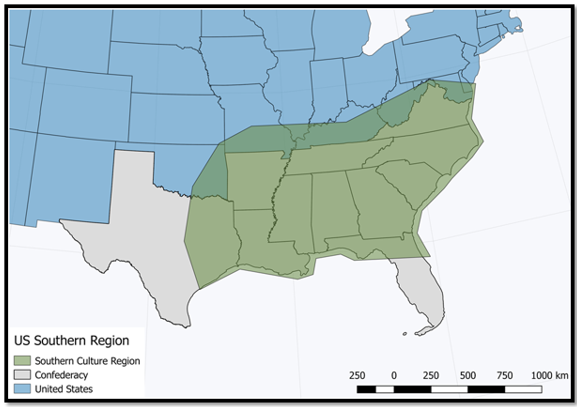

4.2.1 Culture Regions

As discussed in Chapter 1, we can sort the world into regions based on cultural characteristics. A region is an area characterized by similarity or cohesiveness that sets it apart from other regions. Regions are mental constructs; the lines between places are imaginary. When someone talks about the English-speaking world or Latin America, they are referring to culture regions, in this case, a formal culture region because it is a region with people sharing a particular cultural trait or combination of traits. A perceptual or vernacular culture region is what individuals conceive of when they think of a region (what part of the United States is considered “deep south” will depend on an individual’s exposure to ideas regarding the “deep south,” for instance). Functional cultural regions are areas tied together by the function that unites the area (what part of a city gets mail delivery from a particular post office, for instance).

The fuzzy boundaries of the American South. It is not exactly the old Confederacy or the slave states. And it varies from one part to the next.

4.2.2 Cultural Change

A sensible question to ask might be “Where did all the cultures come from?” As people moved into new places, they adapted and changed, and the new places were changed in turn. People change over time as well. Circumstances change in a place. Groups who move into a forest will need to adapt if they cut down all the trees. Groups that adopt a new crop will see their lives change. Divergence could be as simple as borrowing a word to describe an invention. All cultures change over time.

4.2.3 Cultural Diffusion2

The concept of cultural diffusion is critical to understanding the nature of human geography. Cultural diffusion is the spread of culture—both material and nonmaterial—and the methods that account for it, such as migration, communications, trade, and commerce. Because culture moves over space, the geography of culture is constantly changing. Cultural traits that originate in an area (culture hearth) spread outward, ultimately to characterize a larger expanse of territory. The culture region describes the location of cultural traits or cultural communities; cultural diffusion helps explain how and why they got there.

For example, the Pacific Northwest lies within the English-speaking culture region. Nevertheless, there are significant cultural communities within the region in which Spanish, Chinese, Korean, Hindi, Arabic, or another language is dominant. Similarly, while most of the Pacific Northwest is part of the Christian culture region, there also are local cultural communities in which Judaism, Islam, or Buddhism is dominant. What all these languages and religions have in common is that none originated in the Pacific Northwest or even in North America. Similar stories apply to other parts of the world. If you were to visit Australia, for example, you would learn that that continent was once the exclusive domain of an aboriginal cultural community. Because of cultural diffusion, however, most of the present-day Australian people and their homeland bear the unmistakable imprint of European culture—particularly, cultural characteristics that diffused from Great Britain.

Cultural diffusion occurs in different ways, either by relocation or expansion. As suggested by the examples above, migration is an important example. When people move, they take their "cultural baggage" with them. This is known as relocation diffusion. There are uncountable instances, past and present, in which the arrival of migrants has resulted in the appearance of cultural traits or entire cultural communities in areas where they were not previously present. An important modern variation involves businesses that establish facilities or outlets in foreign lands. Thus, the appearance of KFC, Burger King, and Starbucks outside the U.S. is a form of cultural diffusion—and so too the appearance of sushi bars in America.

One subtype of expansion diffusion is known as contagious diffusion. It is based on people’s tendency to copy one another. An example occurs when a farmer looks over the fence, sees a neighboring farmer using a new or different agricultural technique, and adopts it. Similarly, people sometimes adopt a new cultural trait in response to contact with an advertisement, by seeing something on TV, watching a movie, through exposure to the internet, or interacting directly with people who display a particular cultural trait.

Stimulus diffusion, another subtype of expansion diffusion, is common when a specific part of the cultural element is rejected, but the underlying concept is embraced—such as McDonald’s in India. Hindus do not eat beef because they believe cows are holy, so McDonald’s replaces the beef patties with veggie burgers.

Finally, there is a tendency for cultural traits to originate and take hold in large cities and then "trickle down" the settlement hierarchy to smaller cities, towns, and rural areas. Contemporary cultural fads, like hip-hop music or photo selfies, in particular, tend to diffuse in this manner. Because diffusion occurs over time as well as over space, there may be a time lag between the origin of a trait in a large city and its appearance in small towns and rural areas. This subtype of expansion diffusion is known as hierarchical diffusion.

4.2.3.1 Cultural Case Study: The Diffusion of Dancehall

A cultural attribute could diffuse just about anywhere, but that is not how diffusion usually works. Some places are interested in innovation (new things), and some are not. The following example takes one narrowly defined cultural attribute and traces a path to other places. Dancehall, a form of reggae, developed in Jamaica in the late 1970s and grew over time to prominence on the island. One of Jamaica’s main exports is music, and Dancehall became an exported commodity like many other musical forms. In the case of Dancehall, the music is sufficiently defined to allow us to see to where it has diffused. Large markets like North America are visible to us, and we see Dancehall in some of the music of Drake or Rihanna, but other places may seem less obvious. In Brazil, artists such as Lai Di Dai have taken the genre and adapted it to local tastes (which may or may not include changing the language of delivery).

In Germany, the band Seeed (Figure 4.9) has found great success with Dancehall. In Denmark, we find artists like Raske Penge (Figure 4.10) from the live video “Live 2013 (Berlin + Mönchengladbach)”

This Dancehall musical style has moved far beyond its origin. Similar diffusion is found with other musical genres, from the earliest forms of popular music through to the present day.

4.3 FOLK CULTURE

The term folk tends to evoke images of what we perceive to be traditional costumes, dances, and music. It seems that anything with the prefix folk refers to something that somehow belongs in the past and that is relegated to festivals and museums. The word folk can be traced back to Old Norse/English/Germanic and was used to refer to an army, a clan, or a group of people. Using this historical information, folk culture (folktales, folklore, etc.) can be understood as something that is shared first among a group of people and then with the more general population. It is a form of identification. Folk is ultimately tied to an original landscape/geographic location as well. Folk cultures are found in small, homogeneous groups. Because of this, folk culture is stable through time but highly variable across space.

Folk customs originate in the distant past and change slowly over time. Folk cultures move across space by relocation diffusion; as groups move they bring their cultural items as well as their ideas with them.

Folk culture is transmitted or diffused in person. Knowledge is transmitted either by speaking to others or through participating in an activity until it has been mastered. Cooking food is taught by helping others until an individual is ready to start cooking. Building a house is learned through participating in the construction of houses. In all cases, folk cultures must learn to use the locally available resources. Over time folk cultures learn functional ways to meet daily needs as well as satisfy desires for meaning and entertainment. Folk cultures produce distinctive ways to address problems.

Houses tend to be similar within a culture area, since once a functional house type is developed, there is little incentive to experiment with something that may not work. Food must be grown or gathered locally. People prefer variety, so they produce many crops. (In addition, relying on only a few foods is dangerous as one of those food sources may not be available unexpectedly.) Clothing is made from local wool, flax, hides, or other materials immediately available. Local plants serve as the basis of folk medicinal systems. People are entertained by music that reinforces folk beliefs and mythologies, as well as reflects daily life. Folktales/folklore exist as foundational myths, origin stories, or cautionary tales.

Holidays provide another form of entertainment. Special days break the monotony of daily life. A holiday such as Mardi Gras, which has its roots in the Catholic calendar, provides an occasion to flout cultural norms and relieve tension. Another way of providing escape from monotony is provided by intoxicants. Although often not considered when discussing culture, human beings have been altering their mental states for millennia. The production of alcohol, cannabis, tobacco, or coca demonstrates that folk cultures understood the properties of psychoactive substances. Later these substances would be commercialized into modern products.

As folk cultures have receded there has been a return to valuing the folk. The Slow Food movement and the growth of cultural tourism have largely been driven by the desire to experience elements of folk culture. As early as the German Grimm Brothers (19th Century Germany) people have wanted to preserve and promote folk culture. John Lomax (1867–1948) traveled the United States trying to record as many folk songs and folk tales (including slave narratives) as they faded from human memory.

Folk culture can also be expressed as craftsmanship versus factory work. Hand production of goods requires a great amount of knowledge to select materials, fabricate components, assemble, and finish a product. Contrast this with industrial production in which workers need to know very little about the final product and have little relationship with it. This difference in modes of production was first discussed by Ferdinand Tönnies as Gemeinschaft and Gesellschaft. These two words denote the relationship between people and their communities and, by extension, their landscapes. Gesellschaft is the way life is lived in a small community. Gemeinschaft is the way that life is lived in a larger society. The attributes of folk culture can be found in the first column in Table 4.1.

| Folk/Local Culture | Popular Culture |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Table 4.1 Folk/Local Culture as Compared to Popular Culture; Author | Puyallup School District, Washington; Source | Human Geography An open textbook for Advanced Placement, 4.10.17; License | Creative Commons Licensing.

4,4 THE CHANGING CULTURAL LANDSCAPE

It is understood that folk culture has been declining in the face of popular culture for some time. What is driving this decline? There are many things, with different underlying processes. Politically, in the last few centuries, many places have been incorporated into states. These states have often pursued nationalistic policies that made life difficult for minorities of nearly every variety. The growth of a state-sanctioned national culture is the beginning of popular culture (also called "pop" culture). Something as innocuous as public schooling or an official language can serve as a vehicle for promoting national values. Even if there is some overlap between the old culture and the new, the old has been prised loose from its central position in communal life. Economics also plays a role. Small, rural communities have been shrinking globally for centuries, since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution. Leaving the spatial confines of a folk culture makes reproducing that culture very difficult due to its close connection to place. When people migrate to places practicing popular cultures, the pressure to acculturate and assimilate is tremendous.

Infrastructure changes have also aided the diffusion of popular culture. Roads bring in outside people, as well as reduce the friction of leaving a place. The internet has dramatically reduced the friction of distance regarding the diffusion of popular culture. It took decades for tomatoes to diffuse from the Americas to Italy, but we know about a new iPhone months before it even gets released.

The United States is a huge laboratory of cultural interchange. Innumerable distinctive folk cultures were already in the Americas when the Europeans arrived. Waves of people from folk cultures arrived for decades, and they changed the larger culture of the United States.

Places of folk culture aren’t the only places that are changing. Many places with an established popular culture are subject to interaction between different pop culture spheres. At one time immigrants to the United States came from folk cultures. Now they are often from areas of popular culture. The Spanish-speaking world has its popular music stars, and chart-topping musicians from different countries will often collaborate, garnering airplay and sales around the world. World regional cuisines are subject to becoming fads as well.

4.5 POPULAR CULTURE

Popular culture is culture that is bought. Think about your daily life. You work to buy food and clothing, pay your rent, and entertain yourself. The origin of each ingredient in your food could be hundreds or even thousands of miles in either direction. Your clothing almost certainly wasn’t made locally, or even in this country. Your house might look just like any house in any subdivision in North America, placeless and with little connection to local resources.

Popular culture is driven by marketing. Entire industries exist to convince us that our desires and needs will be best met through shopping. Why is this? Because without sales, the companies that produce pop culture will go bankrupt.

Popular culture industries must continuously reinvent themselves. Being popular today is not a guarantee of longevity. To convince consumers that last year’s t-shirt is now unacceptable, it is necessary to promote fashion. Fashion is not just a concept related to clothing. It is the reason that automobile companies make cosmetic changes to their products every year. It is why fast food restaurants continually change some parts of their menus. Without the cachet of fashion, consumers may feel socially disadvantaged. This explains why some people with very limited incomes will spend money on expensive luxuries.

In terms of popular culture, holidays are simply reasons to sell merchandise. The commercialization of Christmas has been increasing for over a century in Western countries. Now it is possible to see Christmas displays in Japan or China, places with few Christians but many available consumers. The same sort of marketing can be seen in the expansion of Halloween globally and the growth of Cinco de Mayo in the United States.

Hierarchical diffusion plays prominently in popular culture diffusion. Larger places tend to generate many of pop culture’s hit songs, clothing styles, and food trends. Diffusion in popular culture is highly related to technology. Although it wasn’t invented as such, the internet has become a venue for advertisement. Clickbait headlines and ad revenue have created an atmosphere where every conversation is a sales pitch.

This hierarchical diffusion means that innovations tend to diffuse from large, well-connected places to other large, well-connected places first, then trickle down to smaller and smaller places. The gap in time that it takes for a new idea or product is known as cultural lag. In some places, there is almost no cultural lag. In very remote places, some innovations take a very long time to arrive. Bear in mind that there are places in the United States that still have no internet service.

Popular culture covers large populations with access to similar goods and services, but the pressing need to sell drives almost incessant modification, generally at a superficial level. Because of this we usually describe popular culture as stable across space but highly variable across time.

The commodification of folk intoxicants mentioned earlier has had a decided effect on the modern world. Low-alcohol beers have a minimal effect on the human body compared to commercially distilled spirits. The opium poppy, dangerous enough in its raw form, can be processed into heroin. The same can be said of coca (now used to produce cocaine) or tobacco. In folk form, these substances tended to be used for ritual purposes. In the context of popular culture, they are used in great quantities. Nevertheless, old folk patterns are still visible in the popular culture landscape. Italians still drink wine, a product they have produced for centuries, only now it might be bought from somewhere else. The Russian climate was good for producing grain and potatoes, which eventually were distilled into vodka.

Selling culture goes well beyond just food and clothing. Popular music and other forms of entertainment (video games, movies, etc.) are huge commercial entities marketing products well outside their places of origin. Movies made in the United States are often being made with the understanding that their international box office sales will be larger than their domestic sales. This is also true of other mass media products. These products are often related to other popular culture products. Companies rely on the familiarity consumers will have with a movie character to sell clothing, toys, video games, conventions, and more movies in that series. When Marshall McLuhan wrote that “The medium is the message” he meant that television would be able to sell itself. The same expression could be expanded to pop culture in general.

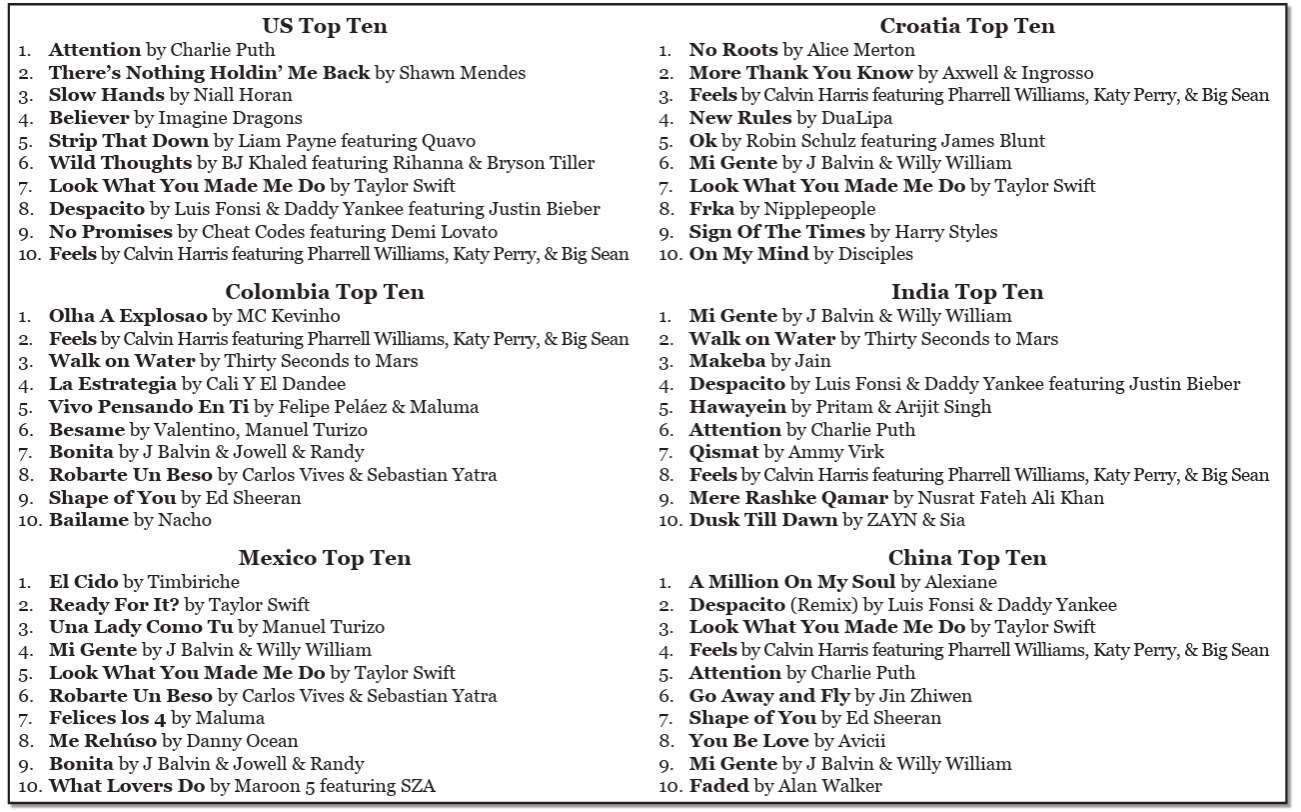

The following graphic (Table 4.2) shows the top ten music charts for the week of September 10–16, 2017. Look closely at them.

Notice the amount of repetition from one chart to the next. Not every chart is a copy of the others, but the similarities certainly bear out the idea of an international music industry.

4.6 THE INTERFACE BETWEEN THE LOCAL AND THE GLOBAL

The basis of popular culture is commerce. As long as a product can be sold, it can survive in the marketplace. This brings up an interesting process. Commodification is the process in which a cultural attribute is changed into a mass-market product. Bear in mind that the mass-market product may not resemble the original product very much. Using a similar fast-food model as McDonald’s, Taco Bell sells ostensibly Mexican products across the world with the notable exception of Mexico. Panda Express is similar to Chinese food. These chains are not in the business of making hamburgers, tacos, or orange chicken. They are in the business of making a profit. Authenticity is irrelevant and probably harmful in the drive to sell more.

The reverse of this process also applies. One aspect of marketing is the incorporation of global products into the local market. Companies will change their products or their entire product lines if doing so is cost-effective and generates a good return on investment. There is even a Central America-based fried chicken chain in the United States. Brands like Sony and Hyundai are highly visible in the American landscape. K-pop bands tour suburban arenas that also host Celine Dion and Paul McCartney.

4.7 GLOBAL CULTURE

Globalization is the integration of the entire world into a single economic unit. This is associated with the frictionless movement of money, ideas, and (to a lesser extent) people. This growing reality has created a newer type of popular culture, global culture. Global culture includes fast food (see Figure 4.11), global brands, and popular culture consumerism.

Where is this fast food restaurant? It could be almost anywhere on Earth. In this case, it is in Malmö, Sweden.

Historically, popular culture was restricted to areas the size of states, or at the very most areas within culturally related spheres (e.g. the English-speaking world). United States culture was defined by a set of characteristics (language, law, settler colonial history, etc.) that translated to a few other places, such as Canada or Australia, but mostly remained place-bound. This is no longer the case. As was mentioned previously, video games are designed in one country to appeal to a global market. The same is true of music, movies, clothes, smartphones, and office productivity software.

At a superficial level at least, the components of life are becoming more homogeneous across large parts of the world. National popular culture producers are merging with international producers, and these international producers have global ambitions. Any sizable popular culture content distributor (EMI Records, Sony, Vivendi Universal, AOL Time Warner, and BMG) is a transnational corporation. The five listed global record labels account for 90% of global music sales.

Starbucks, Toyota, Wyndham, and others have helped reduce the friction of distance by reducing spatial variation. They are not doing this to help people, or to hurt them. Although they will cater to local needs to some degree, they are not in the business of promoting local flavors.

William Gibson wrote, “The future is already here, it’s just not evenly distributed.” In terms of globalization, he was correct. There are still people living in remote areas practicing something similar to a Paleolithic lifestyle. On the other end of the scale, there are people with great wealth who have access to powerful technologies and can live anywhere they desire.

Sometimes globalization affects folk culture. In many places, economic realities have forced people to perform religious activities or relive special events for tourist dollars. Attending luaus in Hawaii or watching Voladores in Veracruz in a quest for authenticity is in itself changing the folk culture that is the center of attention.

This assessment may seem particularly bleak for folk culture, but it is not necessarily completely bad. People survive, and they try to keep the practices that are most valuable to their lives. Folk cultures have a much longer timeline than popular cultures and have proven to be resilient.

4.8 RESISTANCE TO POPULAR CULTURE

Although popular culture has been expanding rapidly at the expense of folk culture, it is not without resistance. Although it is not strictly speaking true, global culture is perceived as largely corporate, secular, and Western. Each of these aspects has its critics.

Anti-globalists fall into two main groups. The first are leftists who oppose the power that has accumulated to corporations and the authoritarian state. The other group are rightists who prefer that power be centered at the state level and who fear that globalization naturally undermines state sovereignty.

In some places, globalization is the same thing as modernization is the same thing as Westernization, which is perceived as secular (or even atheistic), materialistic, and corrupt. Movements such as Al-Qaeda or Islamic State are violently opposed to popular culture, although they would not have a problem if their idea of the ideal culture were to become fully global. Rejecting modern popular culture often also involves elevating a nostalgic, often imaginary golden age as the only acceptable model of society.

Many people feel that symbols and representations of popular culture are erasing the very personality of regional cultures. Resistance to popular culture can come in many forms. Let us revisit the concept of fundamental needs, which are universal, and how they vary geographically. Locally sourced food products, customs, and recipes are pitted against global fast-food giants that provide inexpensive and easy access to ready-made food products. There has been an uprising of farm-to-table businesses, the Slow Food movement, and an emphasis on fair-trade products.

4.9 SUMMARY

Culture, the learned portion of human behavior, is a very broad and very deep topic of human study. Historically humans have lived in small groups practicing folk culture. This was particularly true of the cultures that sprang from the diffusion of agriculture. Many of the folk culture attributes date to this time of human development. The Industrial Age also ushered in the era of popular culture. Popular culture provides the cues that people use to live, work, and interact. Relatively recently has been the rise of global culture, a phenomenon in which large numbers of people in diffuse places are committing the same or similar cultural practices.

4.10 KEY TERMS DEFINED

Artifacts: Tangible goods or technology.

Commodification: The process of transforming a cultural activity into a saleable product.

Contagious diffusion: An expansion diffusion subtype where people copy what they see.

Cultural ecology: The study of human adaptations to physical environments.

Cultural lag: The amount of time it takes for a new product or innovation to reach a population.

Cultural landscapes: Landscapes produced by the interaction of physical and human inputs.

Cultural reproduction: The process of inculcating cultural values into successive generations.

Cultural tourism: A variety of tourism concerned with exploring the culture of a place.

Culture: Learned human behavior associated with groups.

Culture hearth: The historic location of cultural formation.

Culture regions: Geographically grouped areas based on cultural characteristics.

Domesticated: not wild, cannot reproduce without human intervention.

Environmental determinism: The theory that cultural traits are based entirely on the environment.

Expansion diffusion: The adoption of cultural traits based on what is seen being done by other cultures.

Fashion: The latest and most socially esteemed style of clothing or other products and behaviors.

Folk culture: Culture practiced by a small, homogeneous, usually rural group. Also known as traditional culture.

Formal region: A region that has defined boundaries, often a governmental unit such as a country, province, or county.

Friction of distance: As distance increases between places, it becomes more difficult for direct interactions to occur between those places promptly without modern technology

Functional region: A region defined by a relationship, such as the market area of a product, a commuter zone, or an employment market.

Globalization: The global movement of money, technology, and culture.

Hierarchical diffusion: An expansion diffusion subtype based on the desire to adopt attributes of social influencers.

Homogeneous: A population composed of similar people.

Material culture: The objects and materials related to a particular culture.

Mentifacts: Ideas or beliefs.

Nationalism: Pride in your country.

Perceptual region: The internally defined region that exists as the expression of a cultural type. Also known as vernacular region.

Placelessness: The state of having no place. In the modern context, a place is exactly like any other place.

Popular culture: Culture created for consumption by the mass of the population.

Possibilism: The theory that humans can adapt to any environment with technology, and so the environment does not determine cultural behavior.

Relocation diffusion: The migration of people into a new region introduces new cultural traits.

Resistance: Actively pursuing a policy of obstruction of a particular process or undertaking.

Slow Food: Organization promoting the preparation of local, healthy food choices and recipes.

Sociofacts: Forms of social organization.

Stimulus diffusion: An expansion diffusion subtype when part of the adopted cultural trait is changed to meet local needs.

4.11 WORKS CONSULTED AND FURTHER READING

Black, Jeremy. 2000. Maps and History: Constructing Images of the Past. Yale University Press.

“Catholic Pilgrimages, Catholic Group Travel & Tours by Unitours.” n.d. Accessed March 16, 2013. http://www.unitours.com/catholic/catholic_pilgrimages.aspx.

Dicken, Peter. 2014. Global Shift: Mapping the Changing Contours of the World Economy. SAGE.

Dorrell, David. 2018. “Using International Content in an Introductory Human Geography Course.” In Curriculum Internationalization and the Future of Education.

Gillespie, Marie. 1995. Television, Ethnicity and Cultural Change. Psychology Press.

Gregory, Derek, ed. 2009. The Dictionary of Human Geography. 5th ed. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Jarosz, Lucy. 1996. “Working in the Global Food System: A Focus for International Comparative Analysis.” Progress in Human Geography 20 (1): 41–55. https://doi. org/10.1177/030913259602000103.

Knowles, Anne Kelly, and Amy Hillier. 2008. Placing History: How Maps, Spatial Data, and GIS Are Changing Historical Scholarship. ESRI, Inc.

Massey, Doreen B. 1995. Spatial Divisions of Labor: Social Structures and the Geography of Production. Psychology Press.

Mintz, Sidney Wilfred. 1985. Sweetness and Power: The Place of Sugar in Modern History. Viking.

Slow Food USA. Accessed December 28, 2023. https://slowfoodusa.org/.

Sorkin, Michael, ed. 1992. Variations on a Theme Park | Michael Sorkin. 1st ed. Macmillan. http://us.macmillan.com/variationsonathemepark/michaelsorkin.

“The Global Music Machine.” n.d. Accessed December 13, 2017. http://www.bbc.co.uk/ worldservice/specials/1042_globalmusic/page3.shtml.

“The Internet Classics Archive | On Airs, Waters, and Places by Hippocrates.” n.d. Accessed December 15, 2017. http://classics.mit.edu/Hippocrates/airwatpl.html.

“The Medium Is the Message.” 2017. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index. php?title=The_medium_is_the_message&oldid=81254.

4.12 ENDNOTES

- Data Source: World Borders Dataset http://thematicmapping.org/downloads/world_borders.php

- Section Attribution: https://www.oercommons.org/courseware/lesson/16294/overview