Chapter 5: The Geography of Language

Arnulfo G. Ramírez and Juana Ibáñez

STUDENT LEARNING OUTCOMES

By the end of this section, the student will be able to:

- Understand: the diffusion and extinction of languages

- Explain: the relationship between language, identity, and power

- Describe: the distributions of world languages

- Connect: cultures with their linguistic components

CHAPTER OUTLINE

- 5.1 Introduction

- 5.2 Language and its Relationship to Culture

- 5.3 Classification and Distribution of Languages

- 5.4 Language in the Physical, Business, and Digital Worlds

- 5.5 Summary

- 5.6 Key Terms Defined

- 5.7 Works Consulted and Further Reading

- 5.8 Endnotes

5.1 INTRODUCTION

Language is central to daily human existence. It is the principal means by which we conduct our social lives at home, neighborhood, school, workplace, and recreation areas. It is the tool we use to plan our lives, remember our past, and express our cultural identity. We create meaning when we talk on the cell phone, send an e-mail message, read a newspaper, and interpret a graph or chart. Many persons conduct their social lives using only one language. Many others, however, rely on two languages to participate effectively in the community, get a job, obtain a college degree, and enjoy loving relationships. We live in a discourse world that incorporates ways of speaking, reading, and writing but also integrates ways of behaving, interacting, thinking, and valuing. Language is embedded in cultural practices and, at the same time, symbolizes cultural reality itself.

5.2 LANGUAGE AND ITS RELATIONSHIP TO CULTURE

Reflection

This first part of the chapter will enable you to understand three major questions regarding the nature of human language:

- What knowledge of language is available to every speaker?

- What communicative uses of language do speakers utilize in interactive situations?

- How does language reflect cultural beliefs and practices?

5.2.1 Language as a Mental Capacity

To understand the nature of human language, one needs to approach the concept as a complex system of communication. An important distinction should be considered when using the term language. It can be viewed as an internal mental capacity (langue) as well as an external manifestation through speech (parole). As human beings, we can produce and understand countless utterances which are characterized by the use of grammatical elements such as words, phrases, and sentences. With a limited number of language forms, we can produce numerous utterances that can be easily understood by other members of the speech community who share a similar cultural background and language knowledge. This underlying mental capacity is embodied in the concept that language is rule-governed creativity, operating at different grammatical levels in the formation of utterances or sentences. To illustrate, many examples of utterances or sentences can be derived using a limited set of lexical and grammatical words as listed below in Table 5.1.

| Lexical Words | Grammatical Words |

|---|---|

| Nouns (book, class, pencil, student/s, teacher) | Prepositions (on, of, for, from, with) |

| Verbs (forms of “to be,” have, want, write) | Conjunctions (and, but, which) |

| Adjectives (big, good, red, green) | Determinants (a/an/the, her/their, my, this/that) |

| Adverbs (far, near, where, very, no/not) | Pronouns (I, he/she/it, you, mine/yours, they/theirs) |

Table 5.1 English language Lexical and Grammatical Words; Author | Arnulfo G. Ramírez; Source | Original Work; License | CC BY SA 4.0.

Some possible grammatical sentences based on the list of lexical and grammatical words are noted here:

The pencil is near the book. / The student is near the teacher. / The teacher writes with a pencil. /

The green pencil is not far from the book. / I want to be a teacher. / The red pencil is mine. /

She wants to write a good book for her students. / This is my book, but I want you to have it. /

No, the red pencil is not mine. / The teacher wants her students to have a good class. / Where is the teacher? / The book is where? / My class has many students.

5.2.2 Language as a Means of Communication

A salient aspect of language involves the use of the communication system to perform a broad range of conversational acts/functions in “face-to-face” situations. Four major types of conversational acts have been proposed:

- assertives (speaker informs/answers/agrees/confirms/rejects/suggests),

- directives (speaker directs/invites/questions/orders someone else to do something),

- commissives (speaker makes an offer/promise involving some future action),

- expressives (speaker apologizes/evaluates/greets/thanks/expresses opinion/reacts).

Minor secondary acts consist of language use that serves to emphasize (repetition of words/phrases), expand (add additional information), and comment on ongoing talk. Complementary acts can function as conversational fillers (“you know”), starters (“well”), stallers (“uh”), and hedges (“I mean”).

Participants in a conversation tend to follow culturally specific norms. Speaker A greets, gives an order, asks a question, apologizes, and bids farewell and Listener B responds accordingly and uses appropriate conversational language, necessary to maintain the dialogue. Cultural norms specify “What to say/not say in a particular conversational situation?” “How to initiate/end the conversation?” “With whom to talk/not talk during a conversational encounter?” “What locations are appropriate/not appropriate for the use of certain language forms?”

Language use is a joint action carried out usually by two people. Its use may vary due to such factors as the personal characteristics of the participants (friends, strangers, native/non-native speakers, family members, age/sex differences). The conversation may also be influenced by the location (home, school, work, shopping center, political meeting) and the topic of conversation (advice, complaint, news about the family, plans for the weekend).

5.2.3 Language as Cultural Practice

Speakers view language as a symbol of their social identity. As the sayings go: “You are what you speak” and “You are what you eat.” The words that people use have cultural reality. They serve to express information, beliefs, and attitudes that are shared by the cultural group. Stereotype perceptions come into play when we think about race (Asian, African, European, Native American), religion (Christian, Muslim, Jewish, atheist), social status (working class, middle class, wealthy, upper class), and citizenship status (US-born, visa holder, foreigner, undocumented worker). Cultural stereotypes are formed by extending the characteristics of a person or group of persons to all others, as in the belief that “all Americans are individualists and all Chinese are group-followers, collectivists.”

Along with cultural beliefs about groups of people, individuals manifest specific views regarding languages themselves. Some make judgments about Language X as being “difficult to learn,” “not useful in society,” and “too boring.” Others might view Language Y as the means “to get ahead,” “to make friends,” “to complete a college requirement,” or “to participate in the global marketplace.”

According to royal court gossip in the 16th century, King Charles V of Europe had definite opinions about the languages he spoke: French was the language of love; Italian was the best language to talk to children; German was the appropriate language to give commands to dogs; Spanish was the language to talk to God.

Cultural meanings are assigned to language elements by members of the speech community who, in turn, impose them on others who want to belong to the group. Expressions such as “bug off,” “you know,” “you don’t say,” and “crack house” have a common meaning to members of a cultural group. Members in a speech group tend to share a common social space and history and have a similar system of standards for perceiving, believing, evaluating, and acting. Based on one’s experience of the world in a given cultural group, one uses this knowledge (cultural schemata) to predict interactions and relationships regarding new information, events, and experiences.

Schemata function as knowledge structures that allow for the organization of information needed to perform daily cultural routines (eating breakfast, going shopping, planning a party, visiting friends). We can examine cultural patterns of behavior concerning cultural scripts. The concept of cultural scripts is a metaphor from the language of theater. They are the “scripts” that guide social behavior and language use in everyday speaking situations.

“Attending a wedding,” for example, calls for a variety of speech situations (locations and occasions requiring the use of different styles of language). First, there are a series of initial activities (dressing in proper attire, driving to the ceremony, greeting other persons attending the ceremony), then the actual wedding ceremony (participating in the diverse wedding rituals), and finally the post-wedding activities (attending the wedding banquet, engaging in the different activities—eating, dancing, toasting the wedding couple, interacting with other attendees, and taking leave at the end of the festive celebration).

Each speech situation may consist of a range of speech events and different ways of speaking involving various genres/styles: colloquial/informal language, reading of a text, song, prayer, or farewell speech.

At the same time, each speech event might encompass a broad range of conversational acts such as greetings, questions, suggestions, advice, promises, and expressions of gratitude. For individuals who live in a bilingual or multilingual world, verbal behavior is even more dynamic since questions such as Who speaks What language to Whom, When, and Where come into play during most conversational situations.

Sign language, created to communicate effectively with people who cannot hear, varies by culture as well. American Sign Language (ASL) does not use the same motions for its vocabulary as does British Sign Language (BSL) despite English being used in both nonverbal communication styles.

Words are not the only way cultures communicate. Many kinds of nonverbal communication are considered part of the “language” of a culture. For instance, the pitch or intonation of the words used can convey different meanings (paralanguage). Body language can convey culturally significant information (kinesics). For instance, culture determines what a facial expression, a type of body language, means. How close you should stand to one another to be comfortable (proxemics) conveys culturally specific information, too. All the variations in nonverbal communication can be diffused across time and space just like verbal languages.

5.3 CLASSIFICATION AND DISTRIBUTION OF LANGUAGES

Reflection

This second section will facilitate your understanding of the dimensions of language across geographic areas and cultural landscapes. Three main questions are addressed in this section:

- How are languages classified concerning issues of national identity and genealogical considerations?

- What are the major language families of the world, and how many speakers make use of the respective languages?

- How does language use vary in the United States concerning dialects of English and multilingualism?

5.3.1 Diffusion of Languages

Language, like any other cultural phenomenon, has an inherent spatiality, and all languages have a history of diffusion. As our ancestors moved from place to place, they brought their languages with them. As people have conquered other places, expanded demographically, or converted others to new religions, languages have moved across space. Writing systems that were developed by one group of people were adapted and used by others. Indo-European, the largest language family, spread across a large expanse of Europe and Asia through a mechanism that is still being debated. Later, European expansion produced much of the current linguistic map by spreading English, French, Spanish, Portuguese, and Russian far from their native European homelands. Language is disseminated through diffusion but in complex ways. Relocation diffusion is associated with settler colonies and conquest, but in many places, hierarchical diffusion is the form that best explains the predominant languages. People may be compelled to adopt a dominant language for social, political, or economic mobility. Contagious diffusion is also seen in languages, particularly in the adoption of new expressions in a language. One of the most obvious examples has been in the current convergence of British and American English. The British press has published books1 and articles2 decrying the Americanization of British English, while the American press has done the same thing in reverse.3 In reality, languages borrow bits and pieces from other languages continuously. The establishment of official languages is often related to the linguistic power differential within countries. Russification and Arabization are just two implementations of processes that use political power to favor one language over another.

5.3.2 Classification of Languages

There is no precise figure as to the total number of languages spoken in the world today. Estimates vary between 5,000 and 7,000, and the accurate number depends partly on the arbitrary distinction between languages and dialects. Dialects (variants of the same language) reflect differences along regional and ethnic lines. In the case of English, most native speakers will agree that they are speakers of English even though differences in pronunciation, vocabulary, and sentence structure exist. English speakers from England, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and the United States of America will generally agree that they speak English, and this is also confirmed with the use of a standard written form of the language and a common literary heritage. However, there are many other cases in which speakers will not agree when the question of national identity and mutual intelligibility does not coincide.

The most common situation is when similar spoken language varieties are mutually understandable, but for political and historical reasons, they are regarded as different languages as in the case of Scandinavian languages. While Swedes, Danes, and Norwegians can communicate with each other in most instances, each national group admits to speaking a different language: Swedish, Danish, Norwegian, and Icelandic. There are other cases in which political, ethnic, religious, literary, and other factors force a distinction between similar language varieties: Hindi vs. Urdu, Flemish vs. Dutch, Serbian vs. Croatian, Gallego vs. Portuguese, Xhosa vs. Zulu. An opposite situation occurs when spoken language varieties are not mutually understood, but for political, historical, or cultural motives, they are regarded as the same language as in the case of Lapp and Chinese dialects.

Languages are usually classified according to membership in a language family (a group of related languages) which share common linguistic features (pronunciation, vocabulary, grammar) and have evolved from a common ancestor (proto-language). This type of linguistic classification is known as the genetic or genealogical approach. Languages can also be classified according to sentence structure (S)ubject+(V)erb+(O)bject, S+O+V, V+S+O. This type of classification is known as typological classification and is based on a comparison of the formal similarities (pronunciation, grammar, or vocabulary) that exist among languages.

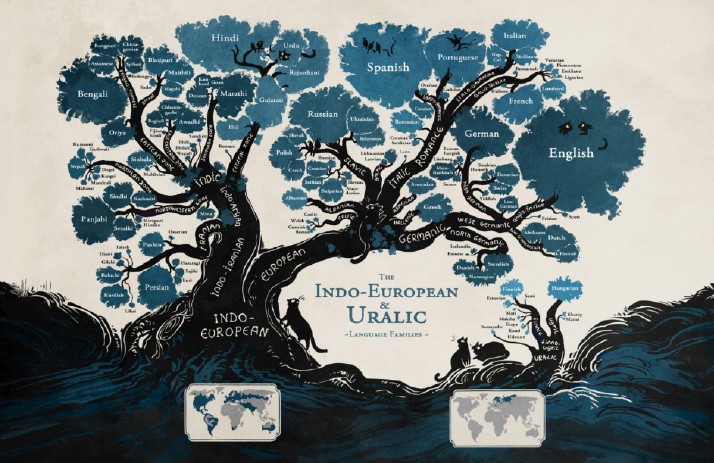

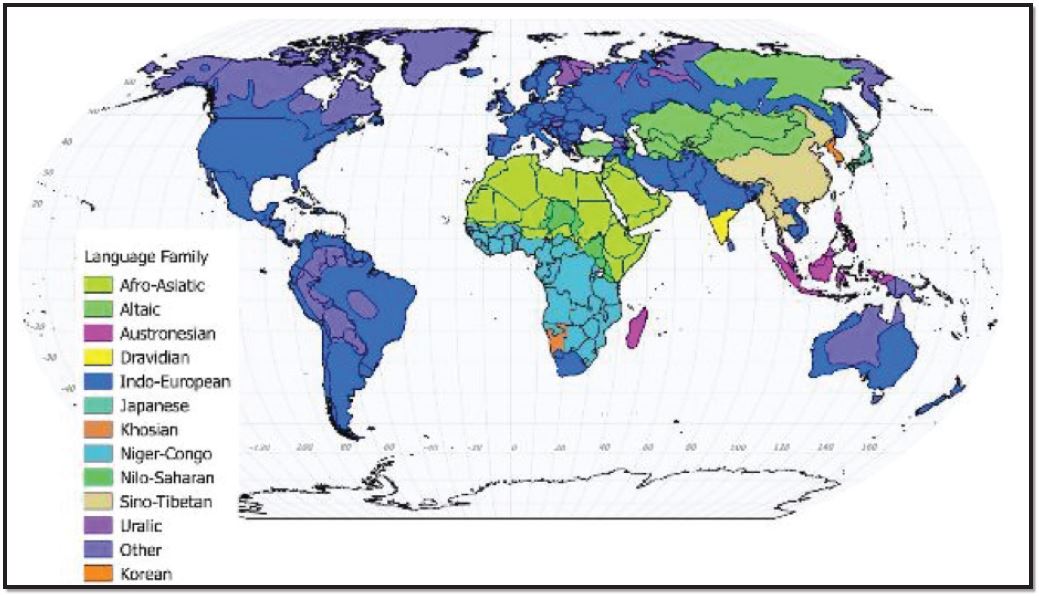

Language families around the world reflect centuries of geographic movement and interaction among different groups of people. The Indo-European family of languages, for example, represents nearly half of the world’s population. The language family dominates nearly all of Europe and significant areas of Asia, including Russia and India, North and South America, Caribbean islands, Australia, New Zealand, and parts of South Africa (see Figure 5.1). The Indo-European family of languages consists of various language branches (a collection of languages within a family with a common ancestral language) and numerous language subgroups (a collection of languages within a branch that share a common origin in the relatively recent past and exhibit many similarities in vocabulary and grammar).

Indo-European Language Branches and Language Subgroups

Germanic Branch

- Western Germanic Group (Dutch, German, Frisian, English)

- Northern Germanic Group (Danish, Swedish, Norwegian, Icelandic, Faeroese)

Romance Branch

- French, Portuguese, Spanish, Catalan, Provençal, Romansh, Italian, Romanian

Slavic Branch

- West Slavic Group (Polish, Slovak, Czech, Sorbian)

- Eastern Slavic Group (Russian, Ukrainian, Belorussian)

- Southern Slavic Group (Slovene, Serbo-Croatian, Macedonian, Bulgarian)

Celtic Branch

- Britannic Group (Breton, Welsh)

- Gaulish Group (Irish Gaelic, Scots Gaelic)

Baltic-Slavonic Branch

- Latvian, Lithuanian

Hellenic Branch

- Greek

Thracian-Illyrian Branch

- Albanian

Armenian Branch

- Armenian

Iranian Branch

- Kurdish, Persian, Baluchi, Pashto, Tadzhik

Indo-Iranian (Indic) Branch

- Northwestern Group (Panjabi, Sindhi, Pahari, Dardic)

- Eastern Group (Assamese, Bengali, Oriya)

- Midland Group (Rajasthani, Hindi/Urdu, Bihari)

- West and Southwestern Group (Gujarati, Marathi, Konda, Maldivian, Sinhalese)

Other languages spoken in Europe but not belonging to the Indo-European family are subsumed in these other families: Finno-Ugric (Estonian, Hungarian, Karelian, Saami), Altaic (Turkish, Azerbaijani, Uzbek), and Basque. Some of the language branches listed above are represented by only one principal language (Albanian, Armenian, Basque, Greek), while others are spoken by diverse groups in some geographic regions (Northern and Western Germanic languages, Western and Eastern Slavic languages, Midland and Southwestern Indian languages).

Major Language Families of the World by Geographic Region

Europe

- Caucasian Family

- Abkhaz-Adyghe Group (Circassian, Adyghe, Abkhaz)

- Nakho-Dagestanian Group (Avar, Kuri, Dargwa)

- Kartvelian Group (Kartvelian, Georgian, Zan, Mingrelian)

Africa

- Afro-Asiatic Family (Arabic, Hebrew, Tigrinya, Amharic)

- Niger-Congo Family (Benue-Congo, Adamawa, Kwa)

- Nilo-Saharan Family (Chari-Nile, Nilo-Hamitic, Nara)

- Khoisan Family (Sandawe, Hatsa)

Asia

- Sino-Tibetan Family (Chinese, Tibetan, Burmese)

- Tai Family (Laotian, Shan, Yuan)

- Austro-Asiatic Family (Vietnamese, Indonesian, Dayak, Malayo-Polynesian)

- Japanese (an example of an isolated language)

Pacific

- Austronesian Family (Malagasy, Malay, Javanese, Palauan, Fijian)

- Indo-Pacific Family (Tagalog, Maori, Tongan, Samoan)

Americas

- Eskimo-Aleut Family (Eskimo-Aleut, Greenlandic Eskimo)

- Athabaskan Family (Navaho, Apache)

- Algonquian Family (Arapaho, Blackfoot, Cheyenne, Cree, Mohican, Choctaw)

- Macro-Siouan Family (Cherokee, Dakota, Mohawk, Pawnee)

- Aztec-Tanoan Family (Comanche, Hopi, Pima-Papago, Nahuatl, Tarahumara)

- Mayan Family (Maya, Mam, Quekchi, Quiche)

- Oto-Manguean Family (Otomi, Mixtec, Zapotec)

- Macro-Chibchan Family (Guaymi, Cuna, Waica, Epera)

- Andean-Equatorial Family (Guahibo, Aymara, Quechua, Guarani)

The number of language families distributed around the world is sizable. The linguistic situation of specific member groups of the language family might be influenced by diverse, interacting factors: settlement history (migration, conquest, colonialism, territorial agreements), ways of living (farming, fishing, hunting, trading), and demographic strength and vitality of the speaker groups. Some languages might converge (many local varieties becoming one main language), while others might diverge (one principal language evolves into many other speech varieties). When different linguistic groups come into contact, a pidgin-type of language may be the result. A pidgin is a composite language with a simplified grammatical system and a limited vocabulary typically borrowed from the linguistic groups involved in trade and commerce activities.

Tok Pisin is an example of a pidgin spoken in Papua New Guinea and derived mainly from English. A pidgin may become a creole language when the size of the vocabulary increases, grammatical structures become more complex, and children learn it as their native language or mother tongue. There are cases in which one existing language gains the status of a lingua franca. A lingua franca may not necessarily be the mother tongue of any one speaker group, but it serves as the medium of communication and commerce among diverse language groups. Swahili, for instance, serves as a lingua franca for much of East Africa, where individuals speak other local and regional languages.

With increased globalization and interdependence among nations, English is rapidly acquiring the status of lingua franca for much of the world. In Europe, Africa, India, and other geographic regions, English serves as a lingua franca across many national-state boundaries. The linguistic consequence results in countless numbers of speaker groups who must become bilingual (the ability to use two languages with varying degrees of fluency) to participate more fully in society.

Some continents have more spoken languages than others (see Table 5.2). Asia leads with an estimated 2,300 languages, followed by Africa with 2,138. In the Pacific area, there are about 1,300 languages spoken, and in North and South America about 1,064 languages have been identified. Europe, even with its many nation-states, is at the bottom of the list with about 286 languages.

| Language | Family | Speakers in Millions | Main Areas Where Spoken |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese | Indo-European | 1197 | China, Taiwan, Singapore |

| Spanish | Indo-European | 406 | Spain, Latin America, Southwestern United States |

| English | Indo-European | 335 | British Isles, United States, Canada, Caribbean, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, Philippines, former British colonies in Asia and Africa |

| Hindi | Indo-European | 260 | Northern India, Pakistan |

| Arabic | Afro-Asiatic | 223 | Middle East, North Africa |

| Portuguese | Indo-European | 202 | Portugal, Brazil, southern Africa |

| Bengali | Indo-European | 193 | Bangladesh, eastern India |

| Russian | Indo-European | 162 | Russia, Kazakhstan, part of Ukraine, other former Soviet Republics |

| Japanese | Austronesian | 122 | Japan |

| Japanese | Austronesian | 84.3 | Indonesia |

Table 5.2: Ten Major Languages of the World in the Number of Native Speakers (footnote #5)

Other important languages and related dialects, whose total number includes both native speakers and second language users, consist of the following: Korean (78 million), Wu/Chinese (71 million), Telugu (75 million), Tamil (74 million), Yue/Chinese (71 million), Marathi (71 million), Vietnamese (68 million), and Turkish (61 million).

5.3.3 Language Spread and Language Loss

Of the top 20 languages of the world, all these languages have their origin in South or East Asia or in Europe. There is not one from the Americas, Oceania, or Africa. The absence of a major world language in these regions seems to be precisely where most of the linguistic diversity is concentrated.

- English, French, and Spanish are among the world’s most widespread languages due to the imperial history of the home countries from where they originated.

- Two-thirds (66 percent) of the world’s population speak 12 of the major languages around the globe.

- About 3 percent of the world’s population accounts for 96 percent of all the languages spoken today. Of the current living languages in the world, about 2,000 have less than 1,000 native speakers.

- Nearly half of the world’s spoken languages will disappear by the end of this century. Linguistic extinction (language death) will affect some countries and regions more than others.

- In the United States, many endangered languages are spoken by Native American groups who reside in reservations. Many languages will be lost in the Amazon rainforest, sub-Saharan Africa, Oceania, aboriginal Australia, and Southeast Asia.

- English is used as an official language in at least 35 countries, including several countries in Africa (Botswana, Kenya, Namibia, Sudan, Tanzania, Uganda, among others), Asia (India, Pakistan, Philippines), Pacific Region (Fiji, Solomon Islands, Vanuatu, New Zealand), Caribbean (Puerto Rico, Belize, Guyana, Jamaica), Ireland, and Canada.

- English is not by law (de jure) the official language in the United Kingdom, the United States, and Australia. English does enjoy the status of “national language” in these countries due to its power and prestige in institutions and society.

- English does not have the highest number of native speakers, but it is the world’s most commonly studied language. More people learn English than French, Spanish, Italian, Japanese, German, and Chinese combined.6

5.3.4 Dialects of English in the United States

At the time of the American Revolution, three principal dialects of English were spoken. These varieties of English corresponded to differences among the original settlers who populated the East Coast.

Northern English

The settlements in this area were established and populated almost entirely by English settlers. Nearly two-thirds of the colonists in New England were Puritans from East Anglia in southwestern England. The region consists of the following states: Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Maine, Connecticut, Rhode Island, Vermont, New York, and New Jersey.

Southern English

About half of the speakers came from southeast England. Some of them came from diverse social-class backgrounds, including deported prisoners, indentured servants, and political and religious persecuted groups. The following states comprise the region: Virginia, Delaware, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia.

Midlands English

The settlers of this region included immigrants from diverse backgrounds. Those who settled in Pennsylvania were predominantly Quakers from northern England. Some individuals from Scotland and Ireland also settled in Pennsylvania as well as in New Jersey and Delaware. Immigrants from Germany, Holland, and Sweden also migrated to this region and learned their English from local English-speaking settlers. This region is formed by the following areas/states: Upper Ohio Valley, Pennsylvania, Maryland, West Virginia, and the western areas of North and South Carolina.

Dialects of American English have continued to evolve over time and place. Regional differences in pronunciation, vocabulary, and grammar do not suggest that a type of linguistic convergence is underway, resulting in some type of “national dialect” of American English. Even with the homogenizing influences of radio, television, the internet, and social media, many distinctive varieties of English can be identified. Robert Delaney (2000) has outlined a dialect map for the United States which features at least 24 distinctive dialects of English. Dialect boundaries are established using diverse criteria: language features (differences in pronunciation, vocabulary, and grammar), settlement history, ethnic diversity, educational levels, and languages in contact (Spanish/English in the American Southwest). The dialect map does not represent the English varieties spoken in Alaska or Hawaii. However, it does include some urban and social (ethnolinguistic) dialects.

General Northern English

Spoken by nearly two-thirds of the country.

New England Varieties

- Eastern New England

- Boston Urban

- Western New England

- Hudson Valley

- New York City

- Bonac (Long Island)

Inland Northern English Varieties

- San Francisco Urban

- Upper Midwestern

- Chicago Urban

Midland English Varieties

- North Midland (Pennsylvania)

- Pennsylvania German-English

Western English Varieties

- Rocky Mountain

- Pacific Northwest

- Pacific Southwest

Southwest English

- Ozark

- Southern Appalachian (Smoky Mountain English)

General Southern English Varieties

- Southern

- Virginia Piedmont

- Coastal South

- Gullah (coastal Georgia and South Carolina)

- Gulf Southern

- Louisiana (Cajun French and Cajun English) 7

5.3.5 Multilingualism in the United States

Language diversity existed in what is now the United States long before the arrival of the Europeans.

It is estimated that there were between 500 and 1,000 Native American languages spoken around the fifteenth century and that there was widespread language contact and bilingualism among the Indian nations. With the arrival of the Europeans, seven colonial languages established themselves in different regions of the territory:

- English along the Eastern seaboard, Atlantic coast

- Spanish in the South from Florida to California

- French in Louisiana and northern Maine

- German in Pennsylvania

- Dutch in New York (New Amsterdam)

- Swedish in Delaware

- Russian in Alaska

Dutch, Swedish, and Russian survived only for a short period, but the other four languages continue to be spoken to the present day. In the 1920s, six major minority languages were spoken in significant numbers partly due to massive immigration and territorial histories. The “big six” minority languages of the 1940s include German, Italian, Polish, Yiddish, Spanish, and French. Of the six minority languages, only Spanish and French have shown any gains over time, Spanish because of continued immigration, and French because of increased “language consciousness” among individuals from Louisiana and Franco-Americans in the Northeast.

The 2015 Census data for the United States reveals valuable geographic information regarding the top 10 states with extensive language diversity.

- California: 45 percent of the inhabitants speak a language other than English at home; the major languages include Spanish, Chinese, Korean, Vietnamese, Arabic, Armenian, and Tagalog.

- Texas: 35 percent of the residents speak a language other than English at home; Spanish is widely used among bilinguals; Chinese, German, and Vietnamese are also spoken.

- New Mexico: 34 percent of the state’s population speak another language; most speak Spanish but a fair number speak Navajo and other Native American languages.

- New York: 31 percent of the residents speak a second language; Chinese, Italian, Russian, Spanish, and Yiddish; some of these languages can be found within the same city block.

- New Jersey: 31 percent of the state’s residents speak a second language in addition to English; some of the languages spoken include Chinese, Gujarati, Portuguese, Spanish, and Italian.

- Nevada: 30 percent of the population is bilingual; Chinese, German, and Tagalog are used along with Spanish, the predominant second language of the Southwest.

- Florida: 29 percent of the residents speak a second language, including French (Haitian Creole), German, and Italian.

- Arizona: 27 percent of the residents claim to be bilingual; most speak Spanish as in New Mexico, while others use Native American languages.

- Hawaii: 26 percent of the population claims to be bilingual; Japanese, Chinese, Korean, and Tagalog are spoken along with Hawaiian, the state’s second official language.

- Illinois and Massachusetts: 23 percent of their respective populations speak a second language at home; residents of Illinois speak Chinese, German, Spanish, and Polish, especially in Chicago; residents of Massachusetts speak Spanish, Haitian Creole, Chinese, Portuguese, Vietnamese, and French.8

The 2019 American Community Survey census data for the Greater New Orleans area (one of the 50 most populous Metropolitan areas in the United States) reveals that 10% of its population speaks a language other than English at home. Spanish (59.4%), Vietnamese (11.2%), French/Cajun (6.4%), Arabic (4.3%), and Chinese (3.5%) are the languages spoken, other than English. In Louisiana as a whole, 7.9% of its population speaks a language other than English at home.9 As a comparison to the rest of the state, in the rest of Louisiana, the top ten languages spoken other than English (and percentage of the population) are Spanish (3.7%), French (1.76%), Vietnamese (0.57%), Arabic (0.25%), Chinese (0.24%), Tagalog (0.13%), German (0.11%), Haitian (0.1%), Portuguese (0.07%), and Thai, Lao, or other Tai-Kadai languages (0.06%).10

These language families in Louisiana do not reflect the adaptations that have occurred in Louisiana from its various immigrants. Those adaptations are what cause languages to change in the long run through time and space. “Cajun” is how the French ancestry native Louisianians (from a Canadian diaspora) self-identify. They may speak Cajun French (a French dialect) or Cajun English. Cajun English merges French words into sentences dominated by English vocabulary. The influence of West African languages brought into Louisiana from enslaved people can be heard in African American Vernacular English with the use of double negatives or verb conjugation differences from standard English grammar. Vocabulary critical to Louisiana identity like gumbo and jambalaya come from the influences of West African culture. Louisiana speaks English with various pronunciations that are different from the rest of the country by dropping a clear “ing” sound with “en” or dropping last consonants, like much of the rest of the south. Language and how it is used in a particular place demonstrates the rich cultural legacy of that place.

5.3.5.1 Top Ten Languages Spoken in U.S. Homes Other Than English

Data from the 2015 American Community Survey ranks the top ten languages spoken in U.S. homes other than English (see Table 5.3). The data highlight the size of the speaker population, bilingual proficiency (fluency in the home language and English), and degree of English proficiency (LEP, limited English proficiency).

| Rank | Language Spoken at Home | Total | Bilingualism % | Limited English % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Spanish | 64,716,000 | 60 | 40 |

| 2 | Chinese | 40,046,000 | 59 | 41 |

| 3 | Tagalog | 3,334,000 | 44.3 | 55.7 |

| 4 | Vietnamese | 1,737,000 | 67.6 | 32.4 |

| 5 | French | 1,266,000 | 79.9 | 20.1 |

| 6 | Arabic | 1,157,000 | 62.8 | 37.2 |

| 7 | Korean | 1,109,000 | 46.8 | 53.2 |

| 8 | German | 933,000 | 85.1 | 14.9 |

| 9 | Russian | 905,000 | 56 | 44 |

| 10 | French Creole | 863,000 | 58.8 | 41.2 |

Table 5.3: Top Ten Languages Spoken in U.S. Homes Other Than English (footnote #9)

Chinese includes Mandarin and Cantonese. French also comprises Haitian and Cajun varieties. German encompasses Pennsylvania Dutch.

While a record number of persons speak a language at home other than English, a substantial figure within each immigrant group claimed an elevated command of English. Overall, some 60 percent of the speaker groups using a second language at home were also highly fluent in English. Limited fluency in English among young children ranged from a high of 55.7 percent in the Tagalog speaker group to a low of 14.9 percent in the German group which included Pennsylvania Dutch users.12

Most immigrant language groups have tended to follow an intergenerational language shift in the United States. This first generation is monolingual, speaking the native language of the group. The second generation is bilingual, speaking both the home language and English. By the third generation, the cultural group is essentially monolingual, speaking only English in most communicative situations.

More recently, some immigrant groups, particularly those with advanced training and degrees in professional fields (technology, health sciences, and business), come to the United States with a high degree of fluency in English. At the same time, the variety of English these persons speak is usually marked by the country of origin (India, Philippines, Singapore, among others). With globalization “new Englishes” have emerged (Indian English, Filipino English, Nigerian English) which challenge the notion of a Standard English variety (British or American) for use around the world.

5.3.5.2 Ethnolinguistic Diversity in Gwinnett County Georgia

Some places in the United States have tremendous ethnolinguistic diversity even if they are not located within one of the top ten states with linguistic diversity. The American Community Survey, aggregate data, 5-year summary file, 2006 to 2010, provides the following profile of ethnolinguistic diversity in Gwinnett County Georgia (Table 5.4).

| Language in Use | Ages 5 years and Above | Percentage of Population |

|---|---|---|

| English | 484,134 | 67.80% |

| All languages other than English | 229,932 | 32.20% |

| Spanish | 124,331 | 17.41% |

| Korean | 17,911 | 2.51% |

| Vietnamese | 12,692 | 1.78% |

| Chinese | 9,184 | 1.29% |

| African languages | 8,750 | 1.23% |

| Serbo-Croatian | 5,097 | 0.71% |

| Gujarati | 4,725 | 0.66% |

| French | 4,713 | 0.66% |

| Other Indo-European languages | 4,232 | 0.59% |

| Hindi | 4,227 | 0.59% |

| Other Asian languages | 4,181 | 0.59% |

| Urdu | 4,088 | 0.57% |

| Russian | 2,487 | 0.35% |

| French Creole | 2,344 | 0.33% |

| German | 2,127 | 0.30% |

| Arabic | 2,038 | 0.29% |

| Tagalog | 1,539 | 0.22% |

| Persian | 1,289 | 0.18% |

| Mon-Khmer, Cambodian | 1,265 | 0.18% |

| Japanese | 1,198 | 0.17% |

| Other Slavic languages | 1,038 | 0.15% |

| Polish | 886 | 0.12% |

| Other Pacific Island languages | 864 | 0.12% |

| Portuguese | 781 | 0.11% |

| Laotian | 645 | 0.09% |

| Thai | 411 | 0.06% |

| Other West Germanic languages | 395 | 0.06% |

| Hmong | 379 | 0.05% |

Table 5.4: Ethnolinguistic Diversity in Gwinnett County Georgia (footnote #13)

5.4 LANGUAGE IN THE PHYSICAL, BUSINESS, AND DIGITAL WORLDS

Reflection

This third part of the chapter will enable you to comprehend the uses of language across different environments. Three major questions are addressed in this section:

- How is a language used to indicate place in the physical landscape?

- How is language exploited for advertising products and services?

- How is the language employed in the digital world to connect multiple senders and recipients in diverse techno formats?

5.4.1 Language and Place Names

The names people give to their physical environment provide a unique source of information about the cultural character of various social groups. Place names often reveal the history, beliefs, and values of a society. Toponymy is the study of place names, and the names people assign to specific geographic sites offer us the opportunity to recognize a country’s settlement history, important features of the landscape, famous personalities, and local allusion to distant places and times. Place names can change overnight, often depending on political factors and social considerations. The change of Burma to Myanmar and Zaire to Congo are two recent examples of changes due to political developments. In the United States, interest in changing the names of places associated with Civil War heroes from the South is an ongoing effort, at times with dramatic confrontations between different social groups.

Toponyms provide us with valuable geographic insights about such matters as where the settlers came from, who settled and populated the area, and what language did the early settlers speak. For example, some place names in Louisiana indicate Finnish influences (Bayou Leskine, Coupee Parish; and Lake Pelto, Terrebonne Parish). Without these place names, the presence of settlers from Finland in Louisiana might not be remembered. Many of the place names found in the United States can be classified in terms of the following major categories:

- natural landscape features (hills/mountains, rivers, valleys, deserts, coastline)

- Hollywood Hills, Blue Ridge Mountains, Chattahoochee River, Rio Grande, San Fernando Valley, Monument Valley, Mojave Desert, Biscayne Bay

- urbanized areas (cities, towns, and streets)

- Williamsburg, VA; Lawrenceville, GA; Chattanooga, TN; New Iberia, LA; Buford Highway, GA; Martin Luther King, Jr. Drive, Ponce de Leon Avenue

- directional place names (East, North, South, West)

- North & South Dakota, West Virginia, North & South Carolina, South Texas

- religious significant names (saints, Biblical names)

- San Antonio, Santa Fe, St. Louis, Sacramento, Santa Barbara, Los Angeles; Bethany, AK; Canaan, VT; Jericho, IA; Shiloh, OK

- explorers and colonizers (French, English, Spanish, Dutch settlers)

- Columbus, OH; Coronado, CA; Balboa Park (San Diego), CA; Cadillac, MI; Hudson, NY; Bronx, NY; Raleigh, NC; Henrico County, VA

- famous persons (presidents, politicians, Native Americans)

- Lincoln, NE; Mount McKinley, WA; Austin, TX; Washington, D. C.; Jackson, MS; Tuscaloosa, AL; Pensacola, FL; Arizona, Mississippi, Utah

- culturally based names (immigrant’s homeland, famous locations)

- New Orleans; New Mexico; New Amsterdam, NY; Troy, NY; Rome, GA; Oxford, MS; Athens, GA; Birmingham, AL; Toledo, OH

- business-oriented names (wealthy individuals, politicians, corporate sponsors)

- Sears Tower, Wrigley Stadium, Trump Towers, Gwinnett County, Dolby Theater, Verizon Center, SunTrust Park

A classification scheme proposed by George Stewart (1982) focuses on ten basic themes that dominate North American toponyms. These include the following categories: descriptive (Rocky Mountains), associative (Mill Valley, CA), commemorative (San Diego, CA), commendatory (Paradise Valley, AZ), incidents (Battle Creek, MI), possession (Johnson City, TX), folk (Plains, GA), manufactured (Truth or Consequences, NM), mistakes (Lasker, NC), and location shift (Lancaster, PA).

5.4.2 Language and the Discourse of Advertising

Commercial advertisement occupies a noticeable expanse in the cultural landscape. An individual text (use and arrangement of specific language forms) is designed to promote or sell a product within a social context. A commercial text may be accompanied by music and visual depictions. The text may also be accompanied by paralanguage features of oral language (gestures, voice quality, facial expressions are examples of nonverbal communication which will vary by culture) and written language (choice of typeface, letter sizes, range of colors).

The advertisement itself brings up several discourse concerns: Who (seller) is communicating with Whom (consumer) and Why (inform/convince/persuade about the product’s importance/usefulness/uniqueness)? The participants in the discourse may include various message senders/participants: the actor/s in the TV commercial along with the supporting role of the advertising agency and the studio production staff. The receivers may be a specific target group or anyone who sees the advertisement.

Highway billboards, store signs, and product advertisements provide a visual representation of commercial language use in a community. Most billboard structures are located in public spaces and display advertisements to passing motorists and pedestrians. They can also be placed in other locations where there are many viewers (mass transit stations, shopping malls, office buildings, and sports stadiums). Some billboards may be static, while others may change continuously or rotate periodically with different advertisements. In addition, there are product promotions within a retail store, which often involve product placements at the end of aisles and near checkout counters.

Novelty ads can appear on small tangible items such as coffee mugs, t-shirts, pens, and shopping bags. They can be distributed directly by the advertiser or as part of cross-product promotion campaigns. Advertisers use the popularity of cultural celebrities in the worlds of sports, music, and entertainment to promote their products. Even aircraft, balloons, and skywriting are used as moveable means to display advertisements.

Store signs and highway billboards can be viewed as a visual language trail, stretching from point A to point B on Highway X in a specific geographic area. Depending on the population characteristics of a location, diverse forms of advertisement are used to convince the customer that a company’s services or products are the best in quality and price, most useful, and socially desired. A drive through various roads and highways across Louisiana, for example, might indicate how advertisers respond to the diverse population characteristics.

Some important questions regarding language use can be addressed within this multilingual context.

- What types of products are marketed to different ethnolinguistic communities?

- What types of services are advertised to different ethnolinguistic communities?

- What type of products are marketed bilingually or in the language of the ethnolinguistic community?

- What type of services are advertised bilingually or in the language of the ethnolinguistic community?

The visual content and design of an advertisement aimed to draw attention to a specific product might focus on customer needs, such as food, clothing, furniture, restaurants, home and garden, cosmetics and beauty care, auto maintenance, fitness and recreation, travel and hotels, communication, and computers. The advertising style for product promotion often tends to be laudatory, positive, and emphasizing uniqueness. The vocabulary is usually vivid and concrete, involving play-on-words and commercial slogans in some cases. Ads rely primarily on language, and it is the visual content and design that create an interest in the product and persuade people to buy it.

The advertisement of services for the general population and targeted ethnolinguistic communities might encompass health services (doctors, dentists, hospital and emergency care), financial institutions (banks, credit unions, home, and car loans, bail bonds), legal services (lawyers, notary public, public defenders), and community resources (schools, libraries, museums, parks). Customer needs usually dictate what services are available in a specific geographic area. Interest in niche marketing, or ads targeted to a specific social group, represents the strong relationship that exists between cultural and technological changes in contemporary US society.

5.4.3 Language and the Digital World

Social media are computer-mediated technologies that allow multiple senders and receivers to create and share information, ideas, career interests, and other forms of expression via virtual communities and communication networks. Social media use relies on web-based technologies such as desktop computers, smartphones, and tablet computers to create highly interactive formats that allow individuals, communities, and organizations the possibility to share, co-create, discuss diverse topics, and comment on content previously posted online. Social media allow for mass cultural exchanges and intercultural communication among people from different regions of the world.

The term “social media” is often used to indicate that many senders and receivers can communicate almost simultaneously across space and time. At the same time, the term social media can mean social networks (relationships and contacts among many individuals). If one is using the term to mean social networks (who interacts with whom in the linguistic community), then the researcher can “observe” and document the interactional patterns or the researcher can “interview” the participants to determine the type of social networks. Social networks, from a sociolinguistic perspective, can be differentiated based on whether they are “dense” or “loose.” In dense networks, all members know each other. In loose networks, not all members know each other. Networks can also be distinguished by the quality of ties (connections) that exist among the members. In uniplex ties, individuals are connected by one type of relationship (participate in the same swim club, take the same courses at a college, work in the same business). In multiplex ties, members know each other in several different roles (student/friend/classmate; parent/co-worker/neighbor).

The term social media is usually associated with different networking sites such as the following:

- Facebook is an online social network that allows users to create personal profiles, share photos and videos, and communicate with other users.

- X, originally named “Twitter,” is an internet service that allows users to post “tweets” (brief messages totaling 140 characters) for their followers to see in real-time.

- LinkedIn is a network designed for the business community that allows users to create professional profiles, post resumes, and communicate with other professionals and job-seekers.

- Pinterest is an online network that allows users to send photos of items found on the web by “pinning” them and sharing comments with others in the virtual community.

- Snapchat is an application on mobile devices that allows users to send and share photos of themselves performing daily activities.14

Social media take many other forms including blogs, forums, product/service reviews, social gaming, and video sharing. The social networking world has changed the way individuals and organizations use language to communicate with each other. Research findings indicate the significant impact that social media is having on society in the United States and elsewhere.

- Nearly 80 percent of American adults are online, and nearly 60 percent of them use social media.

- Among the adolescent population, 84 percent have a Facebook account.

- Over 60 percent of 13 to 17-year-olds have at least one profile on social media, with some spending more than two hours a day on social network sites.

- Internet users spend more time on social media sites than any other type of web-based site. The use from July 2011 (66 billion minutes) to July 2012 (121 billion minutes) represents a 99 percent increase.

- Young adults, some 33 percent, get their news from social media.

- More than half (52 percent) of internet users use two or more social media sites to communicate with their friends and family.

- In the United States, 81 percent of users look online to get news about the weather, 53 percent for national news, 52 percent for sports news, and 41 percent for entertainment or celebrity news.15

There are both positive and negative effects associated with social media. The positive effects include the ability to document memories, learn about and explore different topics, advertise oneself, and form many friendships. On the negative side, social media often invades personal privacy, fosters information overload, promotes isolation, affects users’ self-esteem, and creates the possibility for online harassment and cyberbullying.

Mapping actual language use in the context of the digital world is problematic. It is a complex communication universe. Unlike the geography of place names and the discourse of advertisements, social networking occurs in a virtual environment, involving many senders/receivers and different computer-mediated technologies. Data “mining” is a technique employed to analyze large-scale social media data fields to establish general patterns regarding the content/topics that emerge from people’s actual online activities. Usage patterns in social media interest many advertisers, major businesses, government organizations, and political parties. Research methods from the social sciences have been used to establish user’s activities with different types of social media technologies. These include pencil-and-paper questionnaires, individual/group oral interviews, and focus group sessions. These methods involve language-driven interactions with a limited number of users who may or may not reveal their actual social media patterns of behavior.

5.5 SUMMARY

Language is a mental capacity that allows members of a speech community to produce and understand a countless number of utterances which include grammatical elements like words, phrases, and sentences. Nonverbal communication is also a cultural component of language.

Language as a means of communication makes use of different communicative acts (orders, questions, apologies, suggestions) performed during conversational situations across varied social contexts. Language is a symbol of social identity and serves to express ideas, beliefs, and attitudes shared by a cultural group. It is reflected in cultural stereotypes, notions about different languages, and behaviors during speech situations which presuppose the use of cultural schemata and cultural scripts.

Languages are commonly classified according to membership in a language family such as Indo-European, Sino-Tibetan, Indo-Pacific, Mayan, or Niger-Congo. Members within a family are further subdivided into branches (Germanic, Slavic, Finno-Ugric, Indo-Iranian), and the branches into subgroups (English in the Germanic branch; Spanish in the Romance branch).

The distribution of languages around the world is influenced by numerous factors: settlement history, demographic strength, ways of living, and contact with other ethnolinguistic groups. Some languages become more dominant and as a result displace others that may eventually become extinct, leading to language death. The world’s ten most widespread languages include Chinese, Spanish, English, Hindi, Arabic, Portuguese, Bengali, Russian, Japanese, and Javanese.

The number of dialects or varieties of American English has changed over time due to settlement histories and political changes (Louisiana Purchase, Mexican-American War, Spanish-American War, territory annexation). Language diversity and multilingualism continue to be prevalent in the United States. Recent 2015 Census data reveal extensive language diversity in states like California, Texas, New Mexico, New York, New Jersey, Nevada, Florida, Hawaii, Illinois, and Massachusetts. Place names provide us with cultural insights about the significance of geographic locations, important features of the landscape, the recognition of famous personalities, and local references to distant places and times. Diverse forms of advertisement are used to inform and convince customers that the products and services offered are the worthiest in the marketplace.

The use of different social media technologies (Facebook, X, LinkedIn, Snapchat, among others) allows for online interaction between many senders and receivers. Users can create and share information, ideas, photos, career interests, and other concerns via virtual communities and networks.

Geographic mapping of the use and users of web-based technologies (desktop computers, smartphones, and tablet computers) is unattainable at this time. Research methods from the social sciences (questionnaires, oral interviews, focus group sessions) may reveal some insights about the pervasive ways individuals, communities, and organizations communicate in the virtual world.

5.6 KEY TERMS DEFINED

Bilingual: Being able to use two languages with varying degrees of fluency.

Creole: A blended language differentiated from a pidgin language by its more complex grammar and its status as a first language.

Cultural schemata: A system of standards for perceiving, believing, evaluating, and acting.

Cultural scripts: The “scripts” that guide social behavior and language use in everyday speaking situations.

Dialect: Variants of the single language.

Intergenerational language shift: A linguistic pattern of acculturation found in US immigrant groups in which a group shifts from being non-English monolingual to English monolingual.

Language branch: A group of languages that share common linguistics and have evolved from a common ancestor.

Language family: A collection of languages within a family with a common ancestral language.

Langue: The internal mental capacity for language.

Lingua franca: A language used to make communication possible between people who do not share a native language.

Official language: A language that is given a special legal status over other languages in a country.

Parole: The external manifestation of ideas through speech.

Pidgin: A composite language with a simplified grammatical system and a limited vocabulary.

Proto-language: A historic language from which known languages are believed to have descended by differentiation of the proto-language into the languages that form a language family.

Speech community: People who share a similar cultural background and language knowledge.

Speech situations: Locations and occasions requiring the use of different styles of language.

Text: The use and arrangement of specific language forms.

Toponymy: The study of place names.

Typological classification: Classification based on the comparison of the formal similarities in pronunciation, grammar, and vocabulary that exist among languages.

5.7 WORKS CONSULTED AND FURTHER READING

Bloomer, Aileen, Patrick Griffiths, and Andrew John Merrison. 2005. Introducing Language in Use: A Coursebook. London: Routledge.

Chimombo, M. P. F., and Robert L. Roseberry. 1998. The Power of Discourse: An Introduction to Discourse Analysis. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers.

Cook, Guy. 1992. The Discourse of Advertising. London: Routledge.

Crystal, David. 1987. The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Downes, William. 1998. Language and Society, 2nd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Grosjean, François. 1982. Life with Two Languages: An Introduction to Bilingualism. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Hinton, Sam, and Larissa Hjorth. 2013. Understanding Social Media. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Kramsch, Claire. 1998. Language and Culture. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lightfoot, David. 1999. The Development of Language: Acquisition, Change, and Evolution. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers.

Meyerhoff, Miriam. 2006. Introducing Sociolinguistics. London: Routledge.

Ostler, Nicholas. 2005. Empires of the Word: A Language History of the World. New York: HarperCollins Publishers.

Ramírez, Arnulfo G. 1995. Creating Contexts for Second Language Learning. White Plains, NY: Longman Publishers, USA.

Ramírez, Arnulfo G. 2008. Linguistic Competence across Learner Varieties of Spanish. Munich: LINCOM-EUROPA.

Romaine, Suzanne. 1994. Language in Society: An Introduction to Sociolinguistics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Spolsky, Bernard. 1998. Sociolinguistics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Stewart, George. 1982. Names on the Land: A Historical Account of Place-Naming in the United States. Available through Penguin Random House, paperback edition 2008.

Yule, George. 1996. Pragmatics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

5.8 ENDNOTES

- Engel, Matthew. That’s The Way It Crumbles: The American Conquest of the English Language. London: Profile Books, 2017.

- https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2017/jul/13/american-english-language- study

- https://www.nytimes.com/2012/10/11/fashion/americans-are-barmy-over- britishisms.html

- Data adapted from https://www.kaggle.com/rtatman/world-language-family-map and http://jonathansoma.com/open-source-language-map/

- Ethnologue. 2013. https://www.ethnologue.com/world

- Noack, Rick. 2015. “The World’s Languages, in 7 Maps and Charts.” Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/worldviews/wp/2015/04/23/the-worlds- languages-in-7-maps-and-charts/

- Nisen, Max. 2013. “Map Shows How Americans Speak 24 Different English Dialects.” Business Insider. https://www.businessinsider.com/dialects-of-american-english-2013-12

- “Languages.” 2016. Accredited Language Services (blog). https://www. accreditedlanguage.com/category/languages/

- United States Census Bureau. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs/news/ data-releases/2015.html

- United States Census Bureau. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs/news/ data-releases/2015.html

- Accutrans 19. 2023. https://acutrans.com/top-10-languages-of-louisiana/

- Hallock, Jie Zong, Jeanne Batalova Jie Zong, Jeanne Batalova, and Jeffrey. 2018. “Frequently Requested Statistics on Immigrants and Immigration in the United States.” Migrationpolicy.org. February 2, 2018. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/ article/frequently-requested-statistics-immigrants-and-immigration-united-states.

- United States Census Bureau. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs/news/ data-releases/2015.html

- “What Is Social Media? – Definition from WhatIs.com.” 2018. https://whatis.techtarget.com/definition/social-media.

- “Social Media.” 2018. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Social_ media&oldid=855175226.