Chapter 6: Religion

David Dorrell and Molly McGraw

STUDENT LEARNING OUTCOMES

By the end of this section, the student will be able to:

- Understand: the significance of religion as a historical spatial phenomenon

- Understand: the world’s major religions and their fundamental beliefs

- Explain: the significance of sacred spaces and places to understandings of culture locally, regionally, and globally

- Describe: the hearths and diffusion patterns of the major religions of the world

- Connect: religious belief and values to trade, colonialism, and empire

CHAPTER OUTLINE

- 6.1 Introduction

- 6.2 Overview of Major Religions

- 6.3 Diffusion of Major Religions

- 6.4 Religious Conflict

- 6.5 Summary

- 6.6 Key Terms Defined

- 6.7 Works Consulted and Further Reading

- 6.8 Endnotes

6.1 INTRODUCTION

“I love you when you bow in your mosque, kneel in your temple, pray in your church. For you and I are sons of one religion, and it is the Spirit.”

—Khalil Gibran

This chapter is an exploration of the geography of religion. Like language and ethnicity, religion is a cultural characteristic that can be closely bound to individual identity. Religion can provide a sense of community, social cohesion, moral standards, and identifiable architecture. It can also be a source of oppression, social discord, and political instability.

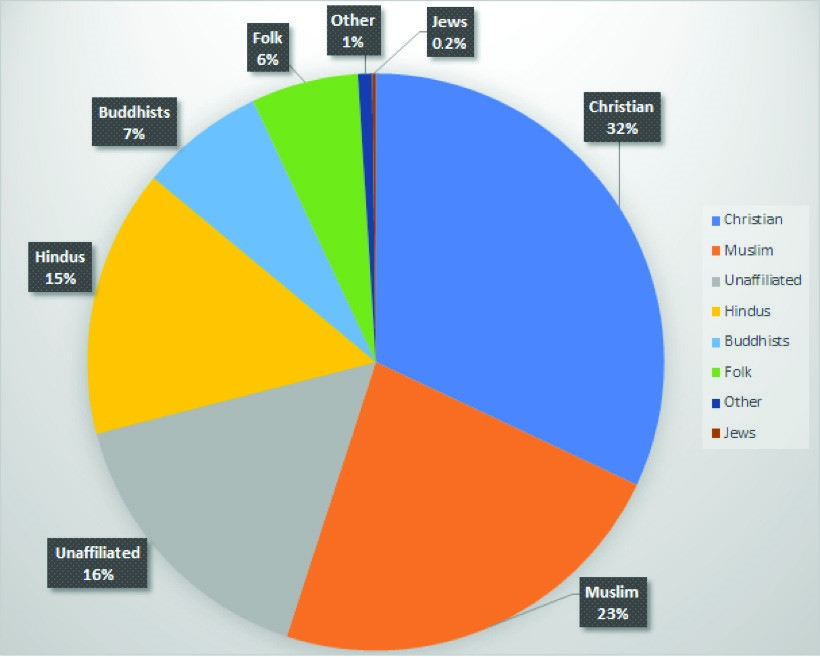

The following pie chart gives us an idea of the relative size (in terms of adherents) of the world’s major religions (Figure 6.1). Bear in mind that these numbers are estimates; there is no world governing body collecting detailed statistics on religion. As one can see, Christians and Muslims make up over half of the world’s population. The next category, the unaffiliated, is a large but diffuse body containing people who do not identify with any religion. Hindus, who cluster in the Indian subcontinent, are the next largest group. Buddhists make up approximately 7% and are closely followed by the Folk religions. The category of Folk religion is similar to that of Unaffiliated—it is a large group of religions that are bound into one category solely for logical consistency. Folk religions may consist of ancestor worship in China, animism in central Africa, or any other number of indigenous, local religions. The Other category contains newer religions that are just gaining their footholds and other religions that may be fading in the contemporary milieu. Judaism is included in the chart, although it has comparatively few adherents (less than 0.5%). It is included for two reasons. First, it provided the cultural spoor for both Christianity and Islam, and second, it is the predominant religion of the modern state of Israel.

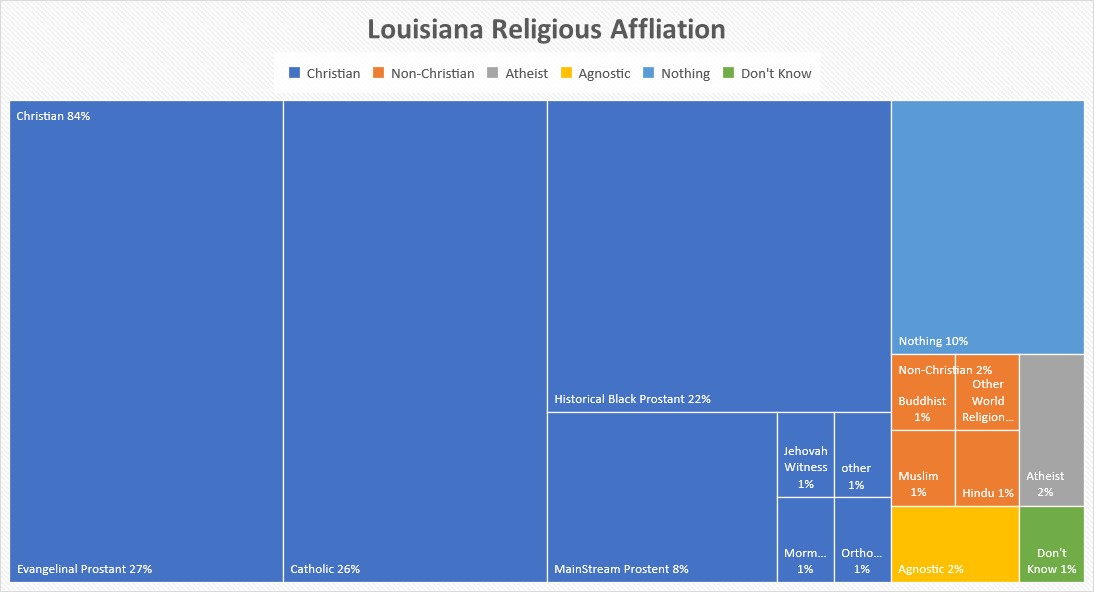

Louisiana’s religious affiliation differs from the global breakdown. As shown in Figure 6.2, Louisiana adults are predominantly Christian (~84%). The next largest group is unaffiliated (~10%). Individuals identifying as Muslim, Jewish, Buddhist, etc. make up the remaining ~15%.

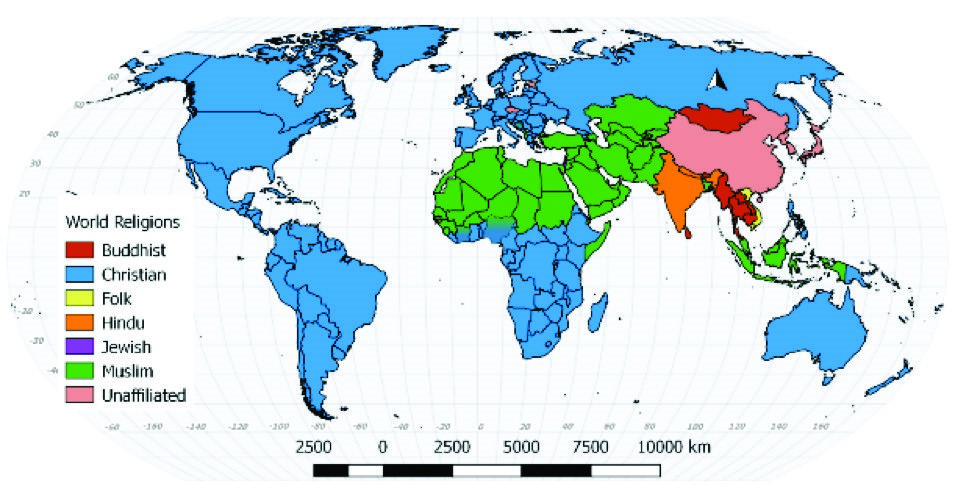

Charts such as these can be somewhat misleading, as can maps of religion (Figure 6.3). All these methods of tabulating religion rely on estimates with varying degrees of accuracy. One problem is determining the predominance of a particular religion. Does predominance require over 50 percent? What if no religion in a country has a majority? In the case of this map, if no religion has a majority, but there are two large religions (for example, Christianity and Islam in Nigeria) then the country is split between the two. If there are numerous fragmented groups, then the group with a plurality is used.

In some parts of the world, some forms of religious expression are discouraged or banned outright. For example, in North Korea, the state ideology is known as Juche, which is not a traditional religion with supernatural elements. The practice of Buddhism or Christianity in North Korea must necessarily be circumspect. In other places, religion has reached the status of being nominal (in name only) in which people identify with a religion, but the practices of that religion have little impact on their daily lives.

State religions are religions that are recognized as the official religion of a country. In some places with a state religion, such as Denmark (Evangelical Lutheran Church) or the United Kingdom (Church of England), the official status of one religion has little effect either on the practice of other religions or on the society at large. In places like Saudi Arabia or Pakistan, however, the official religion (Islam) is closely connected to the power of the state, most obviously in the form of blasphemy laws which allow for state penalties (including death) for violations of religious statutes.

The current religious map of the world is best thought of as a snapshot. The religious landscape has been continuously changing throughout human history and will continue to change in the future. New religions are founded, and old ones die out. New religions are often made using pieces of older religions; Christianity and Islam deriving in part from Judaism and Buddhism deriving from Hinduism are not aberrations but instead are examples of a common occurrence. Within the relatively recent past, it has been possible to watch the creation and diffusion of several new religions just within the United States. Mormonism, the Jehovah’s Witnesses, and Seventh-Day Adventism are all religions that were founded in the U.S. in the relatively recent past.

6.1.1 The Religious Contribution to Culture and Identity

Religions are not isolated social phenomena. They exist within a cultural complex that nurtures and sustains them or, conversely, demeans and undermines them. Religion can be closely bound to other elements of identity—language or nationality. In many societies, the boundaries between religion and social life, family structure, and law and politics are nonexistent. Religion in those places is the center of all life, and everything else revolves around religious concepts. A place that is purely governed by a religious structure is known as a theocracy. There are very few of these in the modern world, although many states have strong religious influence. Many modern societies have built barriers between religious influence and political life. These places are called secular and are much more common in the developed world.

Religion, along with ethnicity and language, are very often core components of an individual’s identity. It can define the way a person sees the world, what clothing is appropriate, gender roles, employment, and even your position within the greater society. As such, it has tremendous cultural influence, and this influence is visible in the landscape. One of the most obvious Louisiana examples is the use of parish instead of county. Parishes arrived with the French and the Catholic Church. Each Catholic Church serves a small area, i.e., a parish. This term was widely used when Louisiana became a state in 1812 and officially adopted in 1845.

6.1.2 Esthetics and Religion

Religion has a motivating factor that few other social phenomena can match. When people are doing something for God, they generally have fewer limits than in other spheres of life. One of the ways this lack of limits is manifest in the landscape is through religious architecture.

Sacred spaces can be religious structures, but they can also be historic battlefields, cemeteries, mountains, or rivers. Anything that humans use to generate a sense of the divine can be considered a sacred space. Sacred spaces have expectations of behavior. In some places, it is still possible to claim sanctuary in a sacred place. The small altars that mark roadside fatalities in Louisiana can be considered sacred spaces, as could a closet that is used as a prayer room.

Elements of culture may be manifest in different types of churches and temples on the landscape, as well as clothing, the food grown, small home devotionals, and festivals. Another way that religion manifests in the visible sphere is through codes of acceptable dress as well as acceptable public behaviors.

A less obvious way that religions may influence the landscape is through religious influences on dietary choices. Food production can be influenced by religion. Many religions have doctrines regarding what is acceptable food and what is not. Halal, Kosher, and Ital are all representative of food restrictions. Religions that prohibit the consumption of pork will probably not have swine farms. Cattle wander through the countryside in India since they are religiously protected from harm. Another effect that religion has on the landscape is the effect of pilgrimage. Many religions have an activity that requires gathering at a particular place. Probably the best-known pilgrimage is the Hajj of Islam, but this isn’t the largest in the world. That would be the Hindu Kumbh Mela. The Camino Santiago is a well-known Christian pilgrimage that ends in Santiago de Compostela, Spain. Pilgrimage is not just visible through the pilgrims but in the entire infrastructure that develops to support the pilgrims. Festivals, such as Louisiana’s Mardi Gras celebration and the annual “Blessing of the Fleet,” have their roots in the Catholic Church.

6.2 OVERVIEW OF MAJOR RELIGIONS

We often break religions into one of two basic types: ethnic and universalizing. Ethnic religions are associated with one group of people. They make little to no effort at proselytizing (converting others), although that possibility may exist. The largest ethnic religion is Hinduism. Judaism is another well-known ethnic religion. Through migration, both religions have become dispersed around much of the world, but they are closely tied to their ethnic groups. Tribal/traditional religions have strong ties to the natural world and little contact or assimilation with the modern world.

Universalizing religions seek to convert others. For some religions, it is a requirement for practitioners to spend part of their lives in missionary work attempting to convert others.

Although the difference between monotheistic religions and polytheistic religions seems unbridgeable, some religions have managed to combine elements of polytheism and monotheism into the same religion. Another way of dividing religions is into the categories of polytheistic (many gods) and monotheistic (one god). For example, in Voudon (Voodoo), entities that had previously represented African gods are recast as Catholic saints, who themselves are semidivine in Catholic cosmology. Combining two religions to create a new religion is known as syncretism.

6.2.1 A Brief Description of the Major Religions

6.2.1.1 Christianity

Christianity is a universalizing, monotheistic religion centered on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth. It dates to the first century AD since the Western world uses the Christian calendar. Christianity began as an offshoot of Judaism and includes the Hebrew Bible (known to Christians as the Old Testament) as well as the New Testament, which contains the teachings of Jesus, as its canonized scriptures. The Christian canon centers on the belief that Jesus of Nazareth was the human-born son of God. Christians believe Jesus was born to a virgin and spent his life teaching and performing miracles such as healing the sick and raising the dead. Tradition has Jesus being crucified by the Romans and raised from the dead three days later. Christians believe in life after death and the forgiveness of sins.

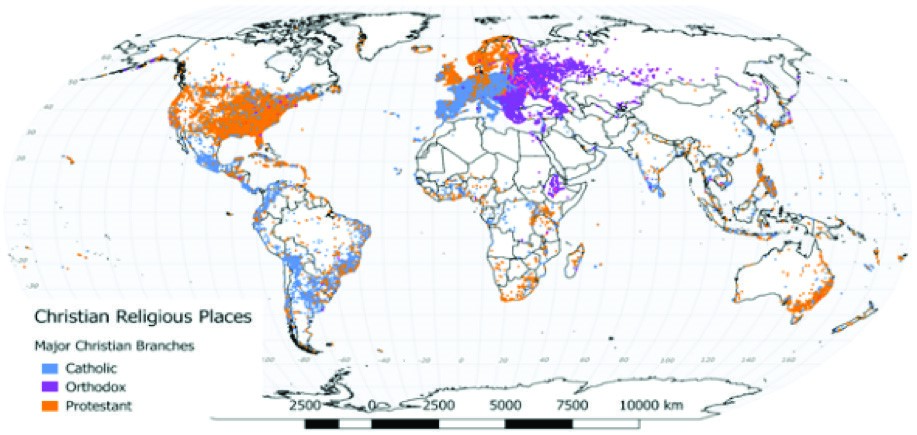

Christianity has three main branches: Roman Catholic, Orthodox, and Protestant (Figure 6.4). Catholic and Orthodox Christianity split roughly one thousand years ago, while the Protestant/Catholic Schism began in the sixteenth century. The split between the Orthodox and Catholic hierarchies centered around the interpretation of the authority of the church’s leader, the Pope, whose authority in the church was final. The split between Protestantism and Catholicism, i.e., The Reformation, mostly centered on politics and some practices conducted by the Catholic Church that the future Protestants did not believe were suitable for a religious organization.

The three branches of Christianity have their spatiality, with a great deal of overlap between them. Orthodox Christianity is mostly seen in Russia, Eastern Europe, and Southern Europe with notable examples in Africa (Ethiopia) and in places where large numbers of people from these places have migrated (the United States, Canada). Catholic Christianity is seen in a wider range of places. It largely formed around the historic Roman Empire, then spread to the north and west of Europe. Catholicism did not stop there, however. The age of colonial expansion transplanted Catholicism to such widespread places as the Philippines, much of the Americas and Caribbean, and large parts of Africa. Protestantism is the most recently developed Christian branch, but it has also diffused widely. The initial Protestant countries were in northern Europe, but again due to colonialism, Protestant Christianity was exported to places like the United States, South Africa, Ghana, Australia, and New Zealand. The current expansion of Christianity, particularly in Asia, is largely due to the growth of Protestantism.

Each Christian branch has developed a distinct appearance in the landscape. Orthodox churches are meant to invoke a sense of the divine. Buildings are elaborate, both inside and outside. Catholic churches also tend to be elaborate, in a similar vein to Orthodox churches, but with a different architectural tradition. This is understandable; these two branches of Christianity arose in different places with different ideas of architectural grandeur and beauty. Protestant churches as a collective are less elaborate than their close relatives. This is a reflection of the early history of Protestant churches, which were often specific rejections of the elaborate ceremony and display of the Catholic Church.

6.2.1.2 Islam

Islam is a universalizing, monotheistic religion originating with the teachings of Muhammad (570-632), an Arab religious and political figure. The word Islam means “submission” or the total surrender of oneself to God. An adherent of Islam is known as a Muslim, meaning “one who submits [to God].” Both Islam and Christianity inherited the idea of the chain of prophecy from Judaism. This means that figures, such as Moses (Judaism) and Jesus (Christianity), are considered prophets in Islam. Muslims believe that Muhammad is the very last in that chain of prophecy. The Five Pillars of Islam are the foundation of the faith.

The Five Pillars are as follows:

- Belief in God and his messenger Muhammad. “There is no god but God, Muhammad is his messenger” is the Muslim statement of faith.

- Prayer. Muslims must pray five times per day facing Mecca.

- Alms. Muslims must give money to help the community.

- Fasting. Muslims must fast from sunup to sundown during the 9th month of the Islamic calendar. The period is called Ramadan.

- Pilgrimage. All Muslims must make a spiritual journey to Mecca. The Muslim holy book is the Holy Koran, and they worship in Mosques.

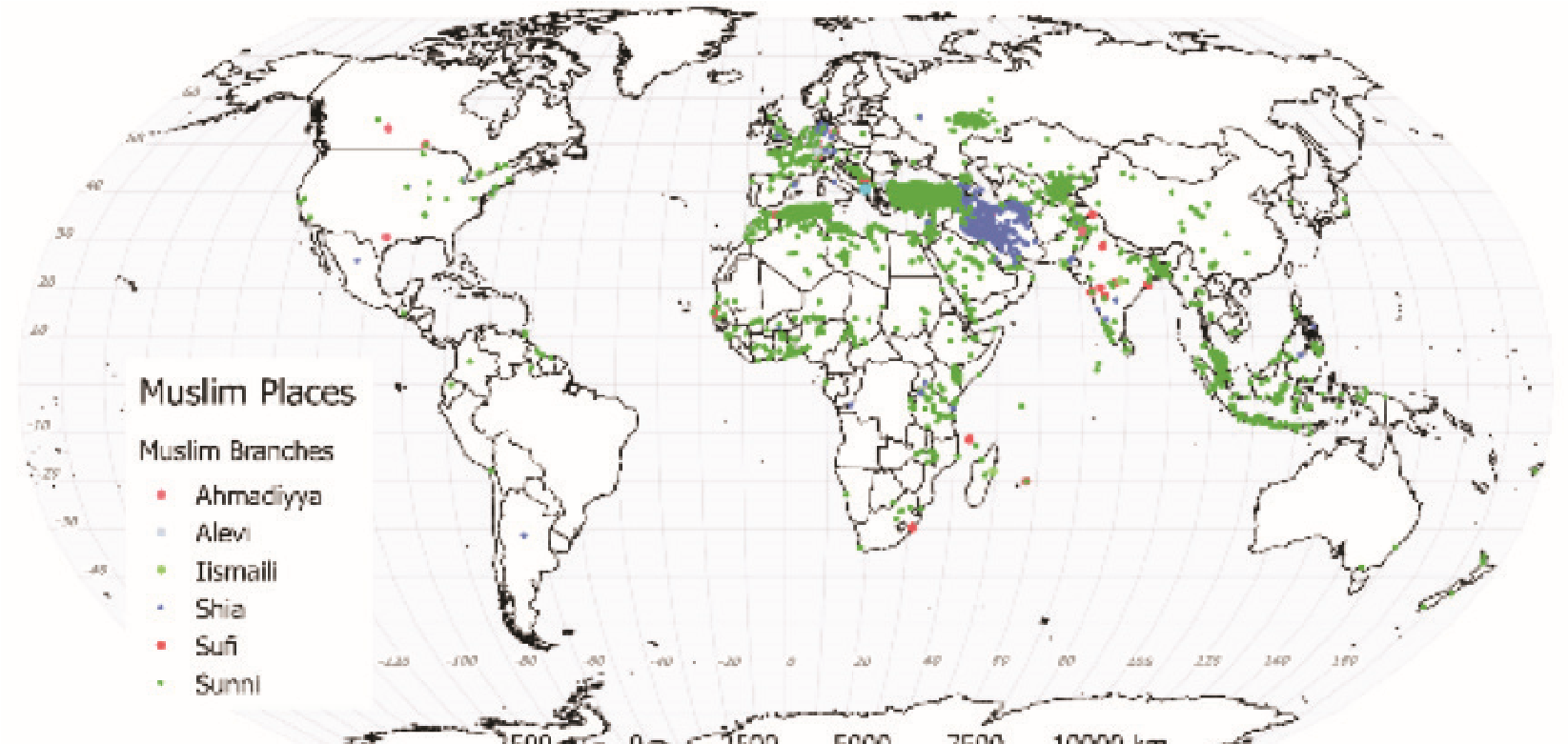

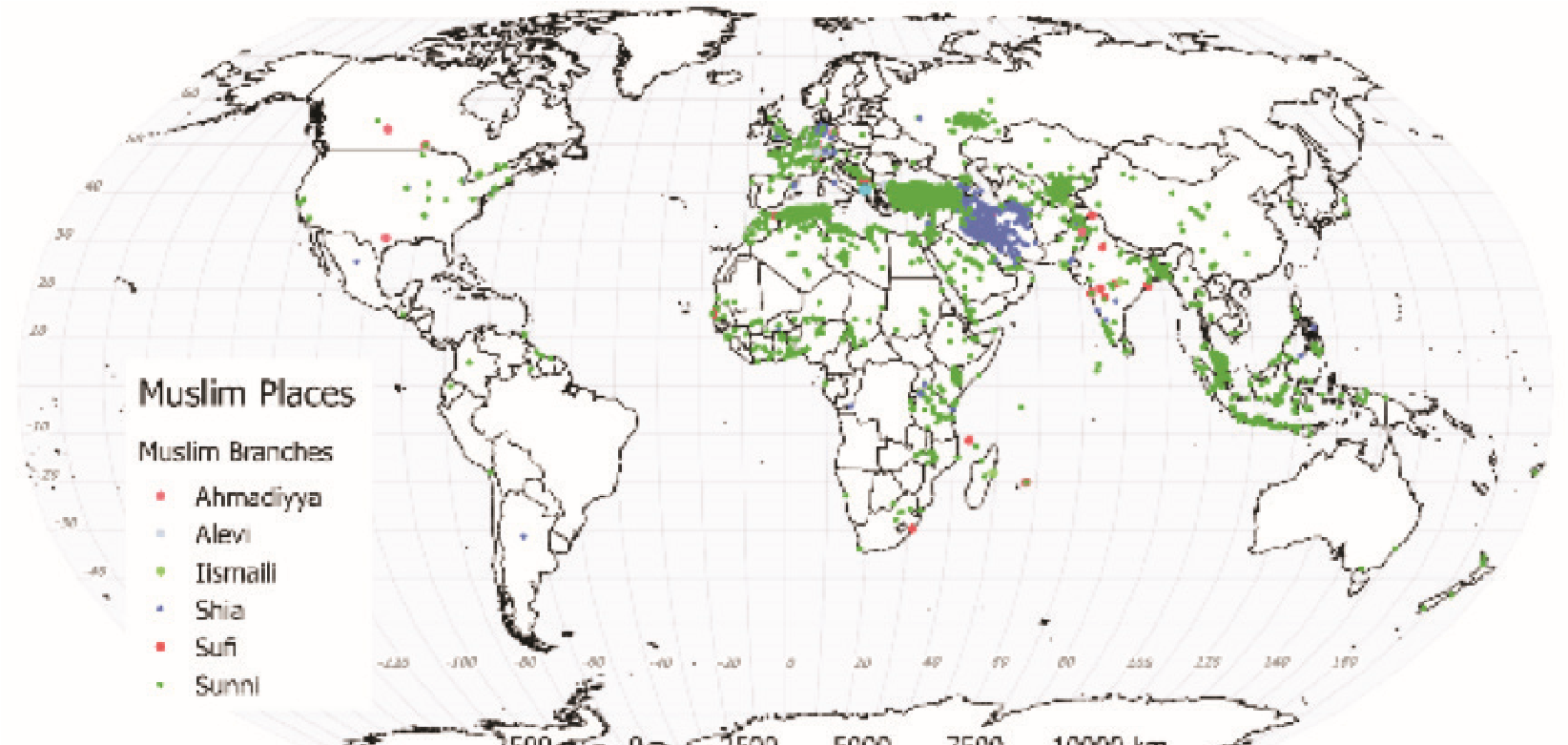

Islam has two main branches and many smaller ones. Of the two main branches—Sunni and Shi’a—Sunni is much larger, comprising roughly 80% of all Muslims (Figure 6.5). The split between the two largest branches of Islam centered around the question of succession upon the death of Muhammad, that is to say, who would be the rightful leader of the Muslim world. The Shiites felt Muhammad’s successor should be someone in his bloodline; while the Sunnis felt a devout and pious individual was acceptable. Currently, there is no single voice for the global Muslim community.

The Muslim world is somewhat more contiguous than the Christian world. This is mostly because the Muslim expansion did not occur in two phases in the same way that Christianity did. As can be seen in the following map, Sunni and Shi’a countries are somewhat spatially separated. Only the countries of Iran, Iraq, Azerbaijan, and Bahrain are majority Shi’a. There are sizable minority Muslim sects in the world. Many of these groups, such as the Ahmadiyya, are subject to discrimination by other Muslim populations and/or governments. The world’s most theocratic governments are Muslim, particularly those of Iran and Saudi Arabia. This is notable in that these two countries are also regional rivals and the two most powerful states in the Muslim world.

6.2.1.3 Buddhism

Buddhism is an offshoot of Hinduism that dates to the fifth century BCE. It was founded by Siddhartha Gautama, i.e., The Buddha, near the modern border between Nepal and India. Gautama was born into an affluent family, rumored to be royalty. As a young man, he enjoyed the privileges of his birth. As he got older, he began to notice the suffering around him. He spent the latter part of his youth traveling and pondering the cause of suffering. While meditating under a Bodhi tree he experienced “The enlightenment,” where he understood the cause and solution to suffering was the “Middle Way.” Gautama developed the Four Noble Truths as a means to end suffering and the “Eight-Fold Path” as a blueprint for living the Middle Way.

The Four Noble Truths are as follows:

- All lives contain suffering.

- The cause of this suffering is desire or wants.

- One must stop these desires or unnecessary wants to end suffering.

- The pathway to stop suffering is to follow the “Middle Way” and to use the Eight-Fold Path to do so.

The Eight-Fold Path6 is summarized in the following:

- Right View or Right Understanding: Insight into the true nature of reality.

- Right Intention: The unselfish desire to realize enlightenment.

- Right Speech: Using speech compassionately.

- Right Action: Using ethical conduct to manifest compassion.

- Right Livelihood: Making a living through ethical and non-harmful means.

- Right Effort: Cultivating wholesome qualities and releasing unwholesome qualities.

- Right Mindfulness: Whole body-and-mind awareness

- Right Concentration: Meditation or some other dedicated, concentrated practice.

The three largest branches of Buddhism are Theravada, Mahayana, and Vajrayana (Figure 6.6). The main differences between the branches are their approaches to canonized doctrine.

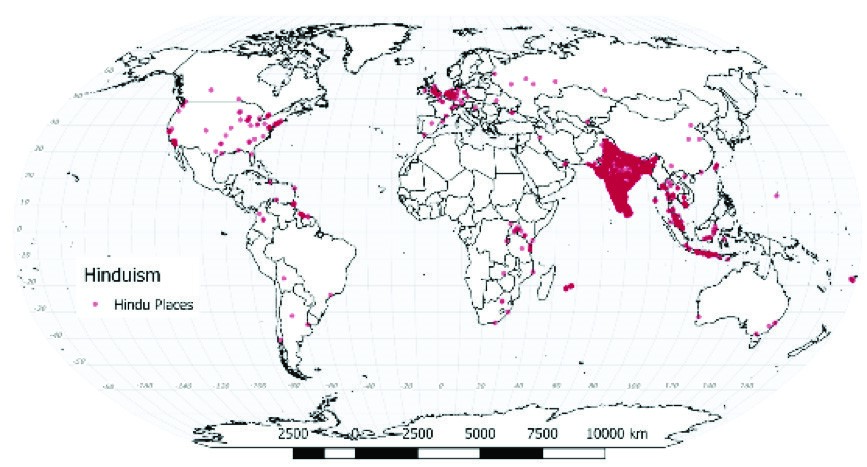

6.2.1.4 Hinduism

Hinduism is a religious tradition that originated in the Indian subcontinent (Figure 6.7). Its origins can be traced to the ancient Vedic civilization (1500 BCE), a product of the invasion of Indo-European peoples. A conglomerate of diverse beliefs and traditions that assembled organically over centuries, Hinduism has no single founder. There are three major beliefs in Hinduism: 1) Reincarnation – Hindus believe all living things have a soul and when a living thing dies the soul is reborn into a new living thing. 2) Karma – Good deeds and actions during one’s lifetime are rewarded with the soul moving to a higher-ranking creature. Similarly, bad deeds and actions are punished with the soul moving to a lesser creature. And 3) Dharma – a set of rules that differ for each living thing that must be followed to move up the ladder in reincarnation. The final step in reincarnation (moksha) is perfection and reuniting with their supreme god, Brahman.

Due to its concurrent growth with Indian civilization, Hinduism has historically been tightly bound to the caste system, although the modern Indian state has worked to ameliorate the more damaging effects of this relationship.

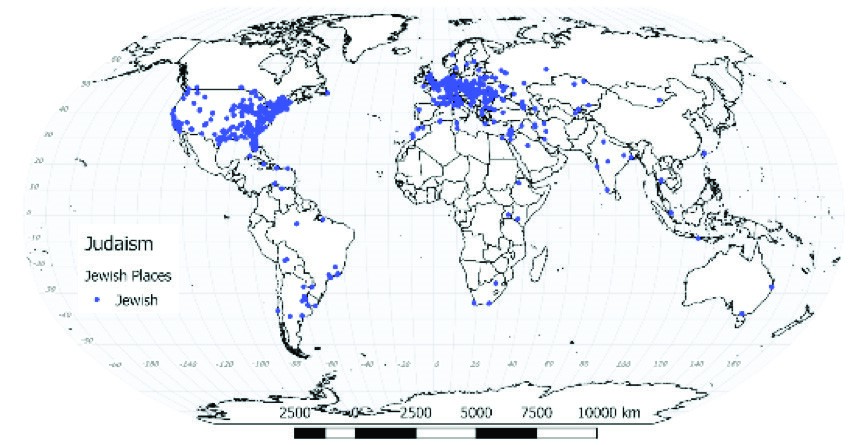

6.2.1.5 Judaism

Judaism is an ethnic monotheistic religion originating in the Bronze Age in the eastern Mediterranean (Figure 6.8). Although it has no single founder, it holds the Torah as its holy book. In the modern context of Judaism, there are three major forms: Orthodox, Conservative, and Reform—each with its own set of interpretations of correct practice. Judaism, as the initial Abrahamic religion, influenced other religions (particularly Christianity and Islam). Jews believe God established a covenant/agreement with them and communicated through prophets. Moses, their most important prophet, received their holy book, the Torah (the first 5 books of the Christian Bible), directly from God. Jews worship in a synagogue and believe the Messiah will come someday.

6.2.1.6 Chinese Religions

Not strictly located in China, Chinese religions are closely tied to Daoism (a nature religion), Confucianism (a philosophy of living), and ancestor worship. Chinese religious structures are associated with people of Chinese descent within and outside of China. Because of the diversity of religious practices and beliefs, this category is best thought of as a complex of beliefs, rather than a defined set of beliefs and practices.

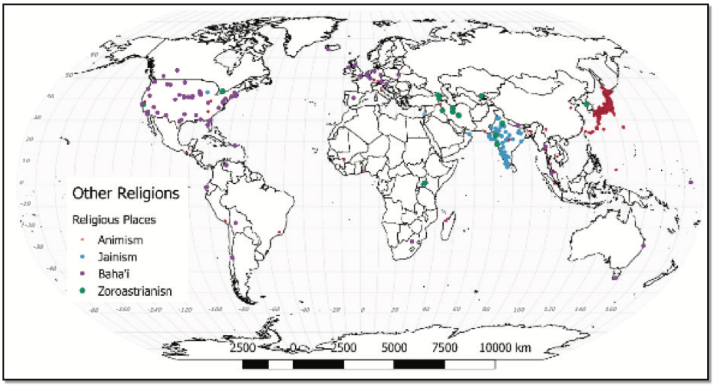

6.2.1.7 Animism, Jainism, Bahai, Shinto, and Others

This catch-all category combines religions that are all quite different. They are here due to their similar ties to places or ethnicities, not because they share any doctrinal or historical connections. Before continuing on a discussion of the following religions, it is important to make a point clear. It is possible to practice more than one religion. Many people in the world practice two or more religions with no sense of contradiction. In many parts of the world, pre-Christian or pre-Islamic beliefs persist alongside the newer religions.

Animism is a broad category, found in a variety of environments (Figure 6.9). The underlying theme is the idea that almost anything in the environment—people, mountains, rivers, rain, etc.—is alive and worthy of recognition as such. Animism is frequently practiced with other ideologies or philosophies.

Baha’i was founded by Mirza Husayn Ali Nuri (1817–1892) in 1863. Baha’i was an offshoot of another religion, Babism, that in itself was a derivative of Islam. Although traditional Muslims believe that Muhammad was the last of the prophets (the seal of the prophets) many religions have been founded on the idea that there could be other, later people who also spoke for God. Baha’is believe that new messengers would be sent to humanity to remind people of their universal relationship to God and one another. The late date and historical context of this religion informed a religion that explicitly rejected racism and nationalism. One of the notable characteristics is that although Baha’is are not one of the larger religions on Earth, they have a temple on every permanently inhabited continent.

Jainism is another ancient religion that arose in India. It is best known for its concept of ahimsa, or nonviolence.

Shinto, the ethnic religion of Japan, is often practiced in conjunction with Buddhism. It is polytheistic and dates back centuries. The most important consideration of Shinto is that the rituals are so ingrained in Japanese national identity that the religion can either be considered vibrant and relevant or moribund and ritualistic, depending on the perspective of the viewer.

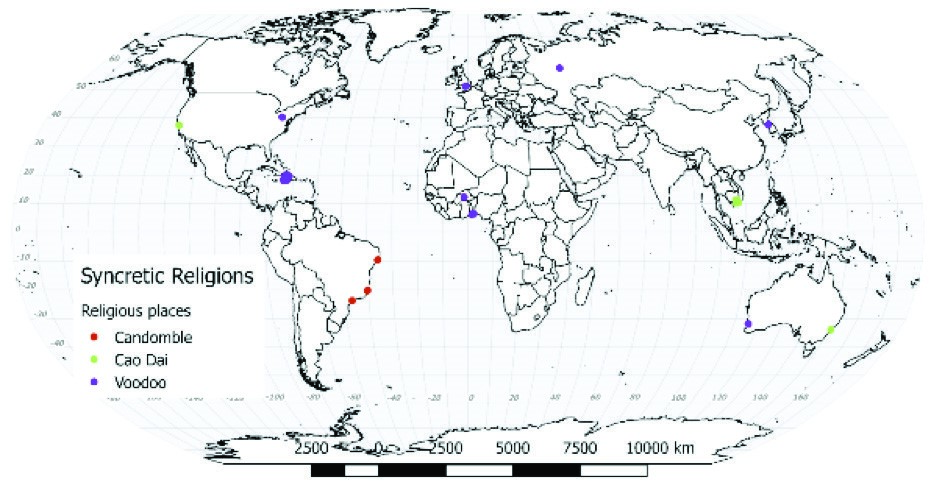

6.2.1.8 Syncretic Religions

Syncretic religions are formed by the combination of two or more existing religions to produce a new religion (Figure 6.10). Some of the larger syncretic religions have already been mentioned, such as Baha’i or Sikhism.

Cao Dai is a religion founded in twentieth-century Vietnam. It has strains of Taoism and Buddhism and represents an attempt to reconcile many diverse religious traditions into a single religion.

Voodoo arose in French Caribbean colonies as a combination of Catholicism and the beliefs of another set of West African peoples, the Ewe and the Fon. Practitioners speak to God using intercessors called loa that function as saints do in both the Catholic and Sufi worlds.

Candomble is a syncretism formed from many West African religious traditions and Catholicism. It has existed in Brazil for centuries. It believes in a creator god (Oludumare) and a series of demi-gods (Orishas).

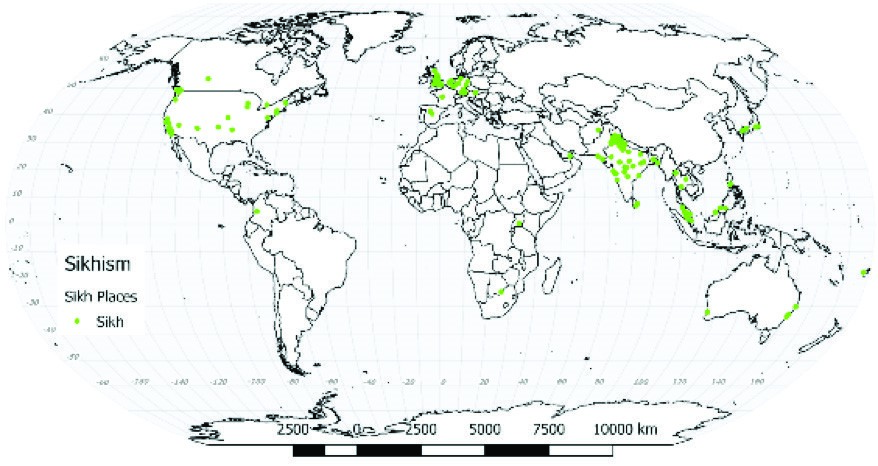

Sikhism is a 15th-century amalgamation of Islam and Hinduism. It is in many ways emblematic of syncretic religions. Syncretic religions are created by the combination of two or more religions, with the addition of doctrinal elements to create cohesion between the disparate pieces. Founded by Nanak Dev Ji (1469–1539) Sikhism reconciles Hinduism and Islam by recasting Hindu gods as aspects of a single god, like the Catholic Trinity. Although heavily associated with the Punjab region of the Indian subcontinent, Sikhism has spread widely through relocation diffusion (Figure 6.11). It has about 26 million adherents.

6.2.1.9 New Religions

Much like any other human phenomenon, new religions are formed continuously. They are usually adaptations or combinations of existing religions. It is impossible to list the most recent arrivals. This category includes such religions as the Unification Church, Seicho no Ie, Rastafarianism, and Wicca.

6.2.1.10 What about the non-religious?

The non-religious category is amorphous. There are no documents of beliefs that all non-religious people must abide by. There is no overarching non-religious creed. It is another catch-all category that contains a large, diverse population with divergent beliefs and practices. Within these categories, however, there are notable manifestations. First, there are those places, such as the former U.S.S.R. and the current Peoples’ Republic of China, which are officially atheistic or non-religious. This label is problematic. It provides only the perspective of the government of these places. In many places that officially have no religions, practitioners simply do not advertise their religious affiliations. In other places, religious attendance has declined to a point where many people have no connection to a particular religious tradition. The label agnostic refers to the idea that the existence of a higher power is unknowable. It is important to point out that religions do not necessarily require the existence of a god-like force. Daoism relies on nature as its driving force.

6.3 DIFFUSION OF MAJOR RELIGIONS

Religion uses nearly all forms of diffusion to reproduce itself across space. Hierarchical diffusion generally involves the conversion of a king, emperor, or other leader who then influences others to convert. Relocation diffusion, often through missionary work, brings “great leaps forward” by crossing space to secure footholds in far-away places. Contagious diffusion is most often seen in a religious context as the result of direct proselytizing. All these forms of diffusion produce patterns of diffusion that are complex. It is impossible to know why certain religions have appeal in particular times or places, but they do, and that appeal can wear off over time.

Another important thing to remember is that the religious landscape is just a snapshot. In the same way that it has always changed, it will continue to do so. These maps can reinforce this idea in that they demonstrate the historical nature of current religious distributions. Remind yourself that these religious expansions occurred at different times. This will help explain why some places will become Buddhist or Christian at one point in history but become Muslim at another.

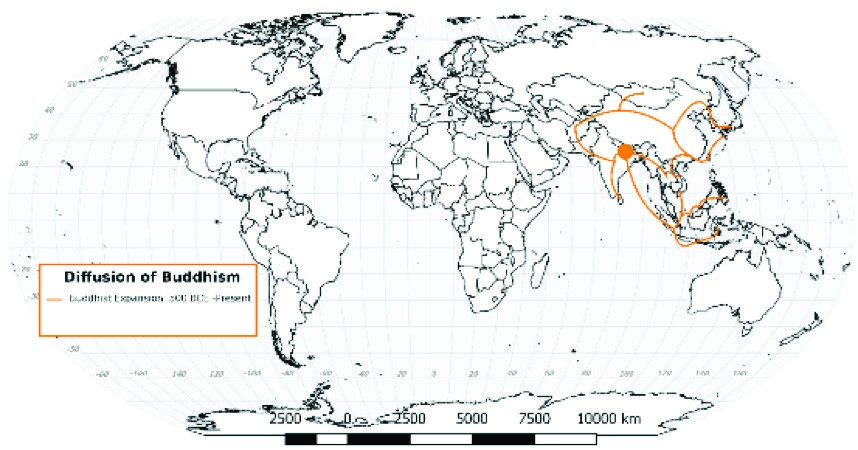

Buddhism originated near the current Nepalese-Indian border. Like many other religions, it spread in other directions, particularly to the south and east (Figure 6.12).

Due to its position as the oldest large, universalizing religion, Buddhism is a good example of the lifecycle of a religion. From its origins, the religion spread across what is now India and Nepal. It spread in all directions, but looking at a current religious map reveals that the process did not end 1500 years ago. Much of its territory on the Indian subcontinent would become mostly Hindu or Muslim. To the east and south, however, the religion continued and expanded. It is not unusual for a religion to prove popular far from its place of origin. That is the key to a successful universalizing of religion.

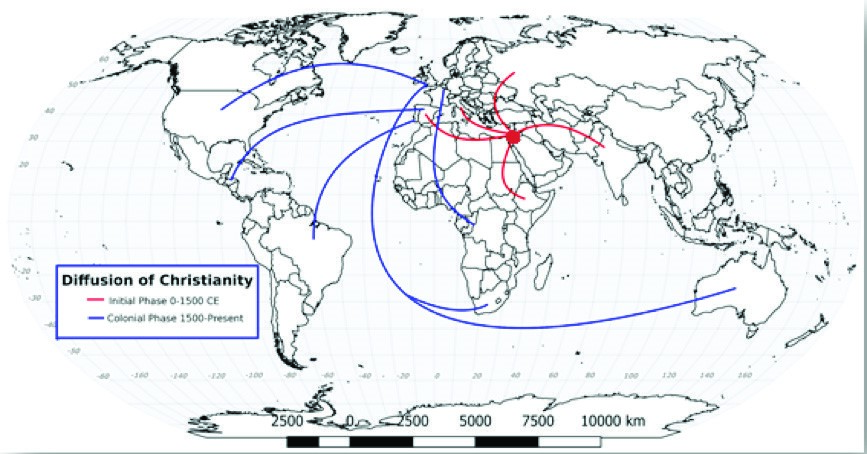

Christianity was founded in the eastern Mediterranean, although much like Buddhism, its greatest successes were found in other parts of the world (Figure 6.13). Christianity initially grew in areas dominated by the Roman Empire, but it would adapt and thrive in many places. With the collapse of the Empire, Christianity became the only source of social cohesion in Europe for centuries. Later, Christianity was promoted through the process of colonialism, and as such, it was modified by the process that distributed it. The spread of Christianity helped drive the process that created the modern world.

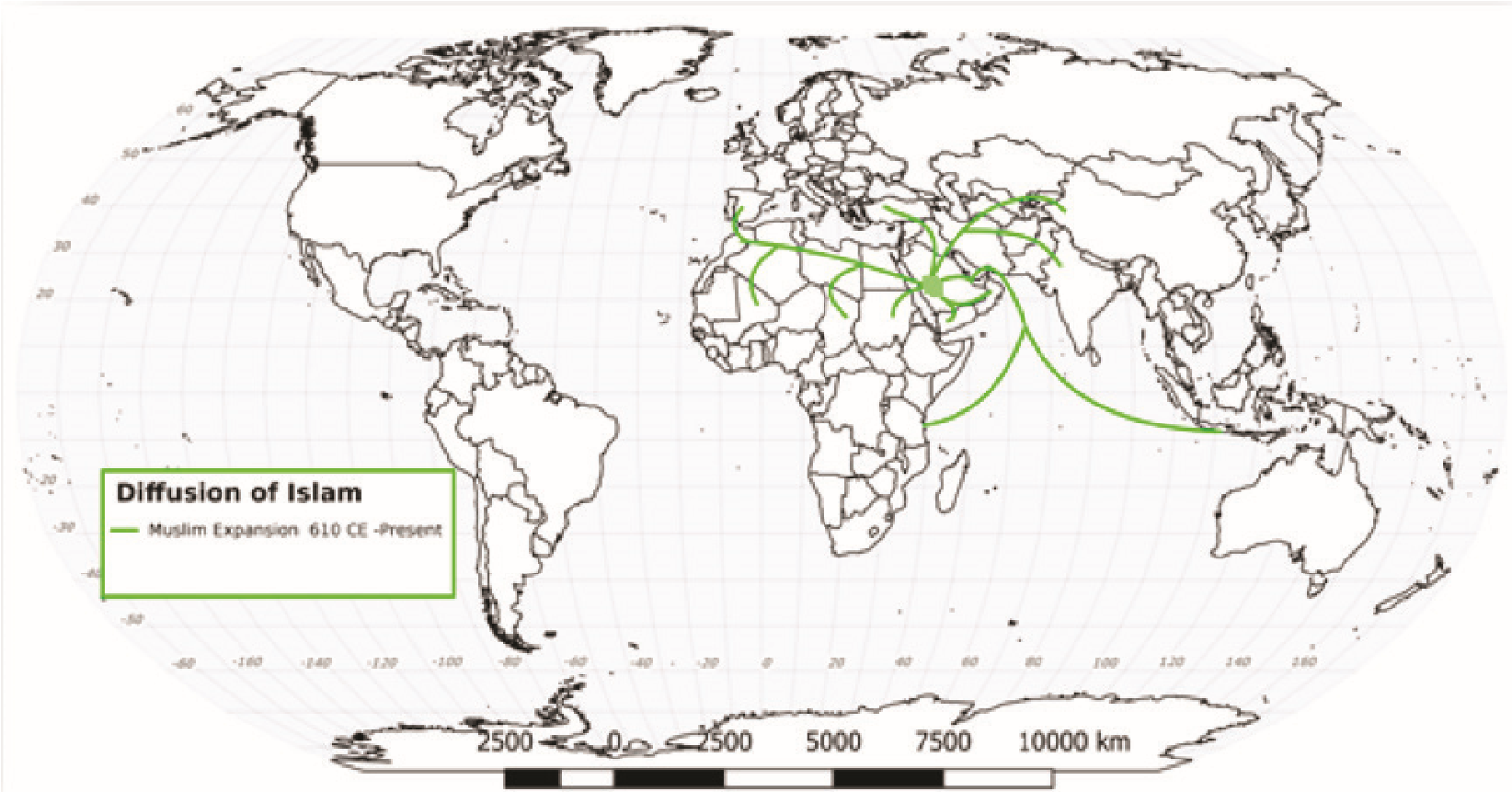

The most recent of the world’s largest religions, Islam is also the one that is expanding the fastest (Figure 6.14). This is not necessarily through conquest or conversion but mostly through current demographics. Islam provides a blueprint for most aspects of life and, as such, has often been associated with rapid expansion driven by military conquest. Although military conquest occurred in the past, military campaigns have been rare since the fall of the Ottoman Empire. The relative distributions of Buddhists, Christians, and Muslims have changed little in half a millennium. Although there has been some migration of Muslims into Western Europe, the percentage of Muslims in each country is small. France has the largest percentage of Muslims at 7.5%. To keep this in perspective, that is much lower than the percentage of Muslims in Spain in 1492.

6.4 RELIGIOUS CONFLICT

Human beings have struggled against one another for a variety of reasons. Religious disagreements can be particularly intense. Sectarian violence involves differences based on interpretations of religious doctrine or practice. The struggles between the Catholic and Orthodox churches, or the wars associated with the Protestant Reformation and Counter-Reformation, are examples of this form of conflict. The current violence seen between Sunni and Shia Muslims is also in this category. Closely associated with this kind of conflict is religious fundamentalism. Religious fundamentalism rests on a literal interpretation and strict and intense adherence to the basic principles of religion. The conflict arises when religious fundamentalists see their coreligionists as being insufficiently pious. Extremism is the idea that the end of a religious goal can be justified by almost any means. Some groups that are convinced that they have divine blessing have few limits to their behavior, including resorting to violence.

Another form of religious violence is between completely different religions. Wars between Muslims and Christians or Hindus and Buddhists have been framed as wars for the benefit or detriment of particular religions. What is described as religious strife, however, is often not. Although some religions are fighting over doctrinal differences, most conflict stems from more secular causes—a desire for political power, a struggle for resources, ethnic rivalries, and economic competition.

The Israel/Palestine conflict is a struggle over territory, resources, and political recognition. The Rohingya crisis in Myanmar has less to do with religion and more to do with differences in ethnicity, national origin, and post-colonial identity. Massacres in Sahelian Africa are better framed as farmers versus herders. The long-running violence between Protestants and Catholics in Northern Ireland is better framed as a violent dispute between one group that holds allegiance with the Republic of Ireland and the other that holds allegiance with the United Kingdom.

This is not to say that religious violence does not exist. It does. The most obvious example of this in recent years has been the emergence of the Islamic State. This organization carries all the worst examples of religious extremism—sectarianism toward other Muslims (the Shi’a), attempted genocide of religious minorities (Yazidis and Christians), and brutal repression through the apparatus of the state.

6.5 SUMMARY

Religion can be key to a person’s identity. It manifests both as an internal sentiment as well as in structures in a landscape. The religious world is always changing, but at a pace that is generally very slow. New religions are created, while other religions may fade away or change. The general historical trend has been toward a small number of universalizing religions gaining ground over local, ethnic religions. Religious differences can lead to conflict, although many conflicts presented as religious have their roots elsewhere. Just like language, religion is another way of sorting people into groups, either for good or bad. Another such way of sorting people is ethnicity, the subject of the next chapter.

6.6 KEY TERMS DEFINED

Agnostic: The belief that the existence of the supernatural is unknown or unknowable.

Atheistic: The belief that there is nothing supernatural.

Branches: Large divisions of a religion.

Canonized doctrine: The officially recognized documents or ideas of a religion.

Ethnic religions: Religions associated with a particular ethnic group.

Monotheism: The belief in one god.

Pilgrimage: A journey to a sacred place.

Polytheism: The belief in many gods.

Prophecy: Communication with a supernatural power.

Proselytizing: Seeking converts to a religion.

Religious fundamentalism: The belief in the absolute authority of a religious text.

Sacred spaces: Places associated with a sense of the divine.

Sanctuary: A haven or place of safety, often defined by law.

Schism: The fracturing of an organization.

Sectarian violence: Violence between different sects of the same religion.

Secular: A condition of separation between a state and any religion.

State religion: The official religion of a state. This is not the same as a theocracy.

Syncretic religion: A religion formed by the combination of other religions.

Theocracy: A state ruled by religious principles.

Universalizing religion: A religion that seeks converts.

6.7 WORKS CONSULTED AND FURTHER READING

Alcalay, Ammiel. 1992. After Jews and Arabs: Remaking Levantine Culture. 1st edition. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Black, Jeremy. 2000. Maps and History: Constructing Images of the Past. Yale University Press.

“Buddhist Pilgrimage Tours | Pilgrimage Tour | Buddha Darshan Tour | Buddha Tours | Buddhist Destination | Holy Buddha Places | Hotel In Buddhist Destinations | Buddhist Temples | Buddhist Monasteries.” n.d. Accessed March 17, 2013. http://buddhistpilgrimagetours.com/.

Cao, Nanlai. 2005. “The Church as a Surrogate Family for Working Class Immigrant Chinese Youth: An Ethnography of Segmented Assimilation.” Sociology of Religion 66 (2): 183–200.

“Catholic Pilgrimages, Catholic Group Travel & Tours by Unitours.” n.d. Accessed March 16, 2013. http://www.unitours.com/catholic/catholic_pilgrimages.aspx.

Dorrell, David. 2018. “Using International Content in an Introductory Human Geography Course.” In Curriculum Internationalization and the Future of Education.

“Global-Religion-Full.pdf.” n.d. Accessed August 22, 2017. http://assets.pewresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/11/2014/01/global-religion-full.pdf.

Gregory, Derek, ed. 2009. The Dictionary of Human Geography. 5th ed. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

“Hajj Umrah Packages 2011 | Hajj & Umrah Travel, Tour Operators | Umra Trips 2011: AlHidaayah.” n.d. Accessed March 17, 2013. http://www.al-hidaayah.travel/.

Knowles, Anne Kelly, and Amy Hillier. 2008. Placing History: How Maps, Spatial Data, and GIS Are Changing Historical Scholarship. ESRI, Inc.

“Modern-Day Pilgrims Beat a Path to the Camino | Travel | The Guardian.” n.d. Accessed March 16, 2013. https://marbellaguide.typepad.com/marbella-guide/2011/05/modern-day-pilgrims-beat-a-path-to-the-camino.html.

“OpenStreetMap.” 2018. OpenStreetMap. Accessed January 5, 2018. https://www. openstreetmap.org/.

Thompson, Lee, and Tony Clay. 2008. “Critical Literacy and the Geography Classroom: Including Gender and Feminist Perspectives.” New Zealand Geographer 64 (3):228–33. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-7939.2008.00148.x.

“World Religions Religion Statistics Geography Church Statistics.” n.d. Accessed January 5, 2018. http://www.adherents.com/.

Bank, World. 2017. “Metadata Glossary.” DataBank. Accessed August 20. https://databank.worldbank.org/home

6.8 ENDNOTES

- Data source: Pew Research Center’s Forum on Religion & Public Life 2012. http://www.globalreligiousfutures.org/explorer#/

- Data Source: https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/religious-landscape-study/state/louisiana/

- Data source: Pew Research Center’s Forum on Religion & Public Life 2012. http:// www.pewforum.org/2015/04/02/religious-projections-2010-2050/

- Data source: OpenStreetMap. http://www.geofabrik.de/data/

- Data source: OpenStreetMap. http://www.geofabrik.de/data/

- Data source: Learn Religions. https://www.learnreligions.com/the-eightfold-path-450067

- Data source: OpenStreetMap. http://www.geofabrik.de/data/

- Data source: OpenStreetMap. http://www.geofabrik.de/data/

- Data source: OpenStreetMap. http://www.geofabrik.de/data/

- Data source: OpenStreetMap. http://www.geofabrik.de/data/

- Data source: OpenStreetMap. http://www.geofabrik.de/data/

- Data source: OpenStreetMap. http://www.geofabrik.de/data/

- Adapted from Spiegel International’s Atlas of World Religions, “Buddhism.” https://www.spiegel.de/international/spiegel/atlas-of-world-religions-asian-religions-a-460247.html

- Adapted from https://www.ed.ac.uk/divinity/research/resources/animated-maps

- Adapted from http://www.oxfordislamicstudies.com/article/opr/t253/e17