Chapter 8: Political Geography

Joseph Henderson; Adam Dohrenwend; Juana Ibáñez; and Molly McGraw

STUDENT LEARNING OUTCOMES

By the end of this section, the student will be able to:

- Understand: how political space is organized

- Explain: how states cooperate in military and economic alliances

- Describe: the various types of boundaries and how boundary disputes develop

- Connect: the electoral process in the United States to ethnic, urban/rural, and regional affiliations

CHAPTER OUTLINE

- 8.1 Introduction

- 8.2 Territoriality

- 8.3 State of States

- 8.4 Functional Political Regions—Federalism vs. the Unitary State

- 8.5 The Shape of the States

- 8.6 Supranational Organization—Cooperation Between States

- 8.7 Boundaries and Boundary Dispute

- 8.8 US Electoral Geography

- 8.9 Key Terms Defined

- 8.10 Works Consulted and Further Reading

- 8.11 Endnotes

8.1 INTRODUCTION

Political geography is the study of how humans have divided up the surface of the Earth for purposes of management and control. In the United States, many people think of this subdiscipline as being focused on memorizing the states and state capitals and perhaps learning the location of various countries around the world. These facts do show how politics is reflected on the surface of the Earth, but political geography is much more than a “trivial pursuit” of such information. (From Puyallup pdf 4.1.)

Political geography is a subfield of human geography that examines how politics influences place and how place and its distinctiveness shape the kind of politics that operate there. Geographers always have an eye open toward noticing and evaluating the spatial distribution of phenomena and possible resulting unevenness. In the case of political geography, this translates to examining how political structures are distributed across the world, understanding the context of why political structures operate where they do, and the impact this has on people’s everyday lives and the global world order, or how power is distributed internationally. Knowing the locations of countries and states is the fundamental foundation for the study of political geography, but the subject matter includes many other topics such as military and economic alliances, boundaries between countries, terrorism, civil-military conflicts, and the geography of the electoral process, for instance (Rosenfeld and Burtch).

Looking beyond the patterns on political maps helps us to understand the spatial outcomes of political processes and how political processes are themselves affected by spatial features. Political spaces exist at multiple scales, from a kid’s bedroom to the entire planet. At each location, somebody or some group seeks to establish the rules governing what happens in that space, how power is shared (or not), and who even has the right to access those spaces. This is also known as territoriality. (From Puyallup pdf 4.1.)

8.2 Territoriality

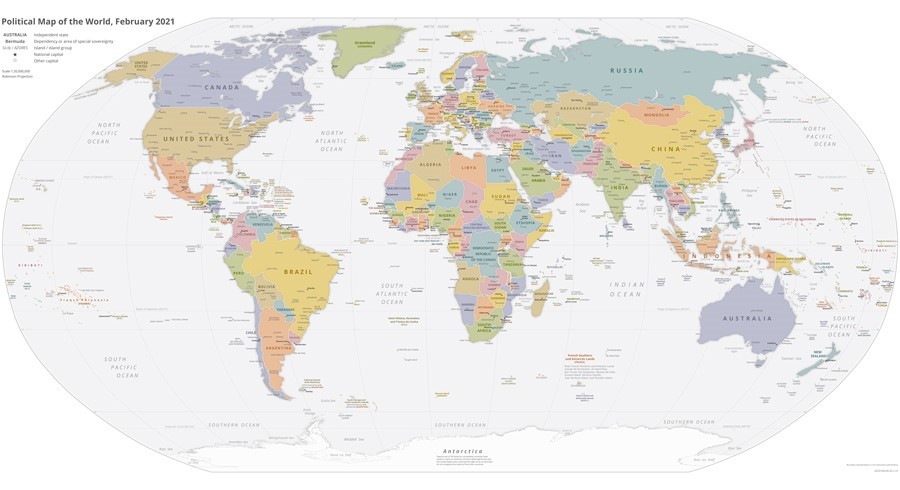

Independent states are the primary building blocks of the world political map. A state (also called a nation or country) is a territory with defined boundaries organized into a political unit and ruled by an established government that has control over its internal and foreign affairs. When a state has total control over its internal and foreign affairs and is recognized as an entity by the world, it is called a sovereign state. A location claimed by a sovereign state is called a territory. According to the United Nations, in 2023 the world had 193 member states (Figure 8.1); however, many of those nations dispute their boundaries. Also, Vatican City is a sovereign state that is not a voting member of the United Nations, so there are 194 recognized sovereign states.

This number of recognized sovereign states changes through military conquests or the devolution, or breakup, of states. For example, the United Kingdom has devolved over the past 70 years as the Republic of Ireland has broken away from the UK, and a new referendum may occur in the next few years to decide whether or not Scotland will become independent. Another example of the creation of new states occurred after the breakup of the Soviet Union in 1991 when fifteen states were created from within the Soviet Union’s former boundaries. If the Russian Federation (commonly referred to as “Russia”) succeeds in acquiring Ukraine as part of its territory, the number of sovereign states will be reduced by one. An example of an unsuccessful attempt at sovereignty is by an entity known as the “Islamic State”; it has tried to establish its state in portions of Syria and Iraq, but its legitimacy is not recognized by the international community.

The idea or concept of a state originated in the Fertile Crescent between the Persian Gulf and the Mediterranean Sea. The first ancient states that formed during this time were called city-states. A city-state is a sovereign state that encompasses a town and the surrounding landscape. Often, city-states secured the town by surrounding it with walls, and farmlands were located outside of the city walls. Later, empires formed when several city-states were militarily controlled by a single city-state.

The Agrarian Revolution (also called the Agricultural Revolution) and the Industrial Revolution were powerful movements that altered human activity in many ways. Innovations in food production and the manufacturing of products transformed Europe, and in turn, political currents were undermining the established empire mentality fueled by warfare and territorial disputes. The political revolution that transformed Europe was a result of diverse actions that focused on ending continual warfare for the control of territory and introducing peaceful agreements that recognized the sovereignty of territory ruled by representative government structures. Various treaties and revolutions continued to shift the power from dictators and monarchs to the general populace. The Treaty of Westphalia in 1648 and those that followed helped establish a sense of peace and stability in Central Europe, which had been dominated by the Holy Roman Empire and competing powers. The Holy Roman Empire, which was centered on the German states of Central Europe from 962–1806, should not be confused with the Roman Empire, which was based in Rome and ended centuries earlier. The French Revolution (1789–95) was an example of the political transformation taking place across Europe to establish democratic processes for governance.

The concept of the modern nation-state began in Europe as the political revolution laid the groundwork for a sense of nationalism: a feeling of devotion or loyalty to a specific nation. The term nation refers to a homogeneous group of people with a common heritage, language, religion, or political ambition. The term state refers to the government; for example, the United States has a State Department with a Secretary of State. When nations and states come together, there is a true nation-state, wherein most citizens share a common heritage and a united government.

European countries have progressed to the point where the concept of forming or remaining a nation-state is a driving force in many political sectors. To state it plainly, most Europeans, and to an extent every human, want to be a member of a nation-state, where everyone is alike and shares the same culture, heritage, and government. The result of the drive for nation-states in Europe is an Italy for Italians, a united Germany for Germans, and a France for the French, for example. The truth is that this ideal goal is difficult to come by. Though the political boundaries of many European countries resemble nation-states, there is too much diversity within the nations to consider the idea of creating a nation-state a true reality.

After the concept of the nation-state had gained a foothold in Europe, the ruling powers focused on establishing settlements and political power around the world by imposing their military, economic, political, and cultural influence through colonialism. Colonialism is control of previously uninhabited or sparsely inhabited land. Europeans used colonialism to promote political control over religion, extract natural resources, increase economic influence, and expand political and military power. The European states first colonized the New World of the Americas but later redirected their focus to Africa and Asia. This colonial expansion across the globe is called imperialism. Imperialism is the control of territory already occupied and organized by an indigenous society. These two factors helped to spread nationalism around the globe and have influenced modern political boundaries. (Source: Dastrop and AP.)

8.3 State of States

States in which the territorial boundaries encompass a group of people with a shared ethnicity are known as nation-states. These states are generally homogeneous in terms of the cultural and historical identity of the people, and these groups of people are referred to as a nation. A few current examples of nation-states are Japan, Finland, and Egypt. Nation-states are actually in the minority compared to multinational states, which are states that have more than one ethnicity within their borders. With international migration being a significant phenomenon worldwide, more states are becoming multinational. In contrast, some nations exist but do not have their state, and those nations that desire to become nation-states are known as stateless nations. Many Native American groups in the United States might also be considered stateless nations, especially those who have not received federal recognition like the Houma of Louisiana.

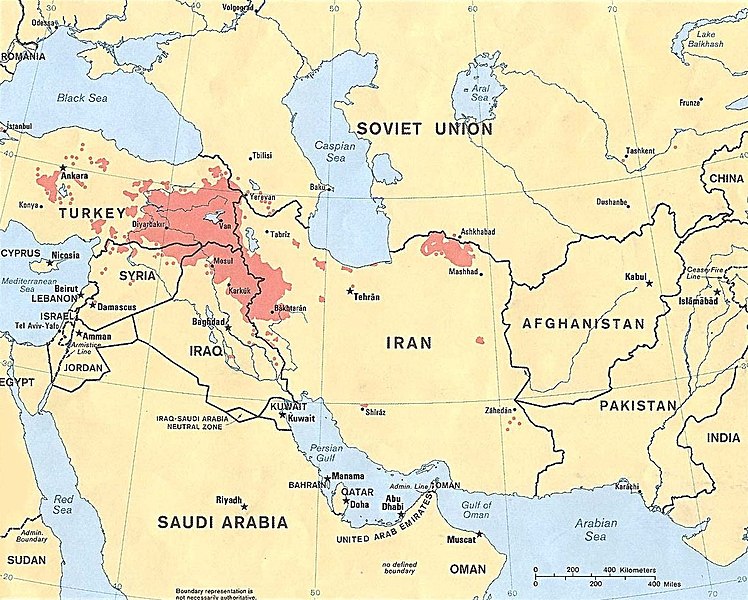

Other examples include the Palestinians living in Israel, Syria, Lebanon, and Jordan and the Kurds living in Iraq, Turkey, Syria, and Iran (Figure 8.2). Both the Kurds and the Palestinians are actively seeking statehood, but serious obstacles must be overcome because the countries where they live are reluctant to grant them independent territories.

The idea of “nation” functions often in very real terms. People root for ball teams, swear allegiance to flags or rulers, and will even fight to the death to preserve and/or honor this imaginary sense of identity. Some people within nations fight to restrict admission to their group as well. Most countries govern who can enter their space, as well as the degree to which individuals can participate in the life of the country, and/or who can become citizens, a legal status that permits one to be legally part of the group.

8.4 Functional Political Regions—Federalism vs. the Unitary State

Politics is first and foremost about power. There are two key types of power: hard power, which operates by force and coercion, and soft power, which operates by fostering consent and attraction.

Politics can be understood in three levels that all intersect in place and impact people’s livelihoods:

- politics essential to state/country survival (examples: elections, war, peace, diplomacy),

- politics that is non-essential to state/country sovereignty but more mundane (examples: Department of Education, Environmental Protection Agency),

- and politics that challenge the existing structures of power (current examples include the Black Lives Matter movement and gun rights advocacy groups in the USA) (Rosenfeld & Burtch).

There are two governmental systems—federalism/federal and unitary systems. Federalism is a system of government with one strong, central governing authority as well as smaller units, such as states or provinces. If the central government grows too strong, then federalism comes closer to a unitary state, where the governing body has supreme authority and dictates how much power the units are allowed to have. In places like Egypt, France, and Japan, where nationalist feelings are strong and there are many centripetal forces like language, religion, and economic prosperity uniting people, a unitary state makes a lot of sense. Unitary systems work best where there is no strong opposition to central control. Therefore, the political elite in a capital city (like Paris or Tokyo) frequently have outsized power over the rest of the country. Fights over local control are minimal, and the power of local (provincial) governments is relatively weak (Figure 8.3).

Many countries have an underdeveloped sense of nationhood and therefore are better suited to use a federalist style of government where power is geographically distributed among several subnational units. This style of governance makes sense when a country is “young”—and is still in the process of nation-building or developing a common identity necessary for the establishment of a unified nationality. Federations may also work best when you have multiethnic or multinational countries. Rather than break into multiple smaller states, a country can choose to give each of its ethnicities or nationalities some measure of political autonomy. If they want to speak their language or teach their specific religion in the local schools, then the central government allows local people to make those decisions. The central government in a federal system focuses on things like national defense, managing interstate transportation, and regulating a common currency. The US began as a federalist system.

Occasionally, a particularly troublesome provincial region or ethnicity will result in a sort of compromise situation, or devolution, in which a unitary system, like China, will grant a special exemption to one region or group to allow that location semi-autonomy or greater local control. Puerto Rico (United States) and Hong Kong (China) are excellent examples, though there are many dozens of other similarly self-governing regions around the globe—most with special names designating their status. This process is often beneficial to the unitary nations to prevent political instability and conflict; however, it can be withdrawn by the central government at any time.

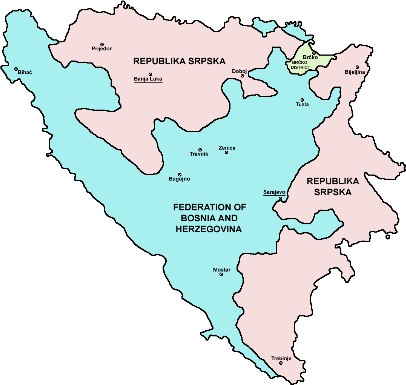

The hostile fragmentation of a region into smaller, political units is called Balkanization. This is often the result of unresolved centrifugal forces pulling the nation apart from within, such as economic disparity and ethnic or religious conflicts. The term “Balkanization” refers back to an area on the Balkan Peninsula of Europe that was part of the Ottoman Empire. After the fall of the Ottoman Empire (defeated in World War I), new countries emerged along predominantly ethnic lines like Albania and Bulgaria. Yugoslavia was formed then but was a multiethnic country controlled by a benign dictator which eventually balkanized into ethnic components including Croatia, Slovenia, and Kosovo. Nowadays, we use this term to refer to any country that breaks apart to form several countries or several states, usually as a consequence of civil war or ethnic cleansing as was seen in Armenia and Azerbaijan, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Serbia. (Figure 8.4)

Most of the written and unwritten rules that govern our lives are established by those with whom we share common territory and identity. The United States of America is a country. Technically, it is a state, but that term applies in America to provinces within the US as well—so be careful when you hear or read “state.” The US is defined by its borders. The vast majority of residents within those borders claim “American” as an important part of their identity; therefore the United States can for the most part be known as a nation, and “American” is our nationality. A nation can include millions of individuals, or it can include far fewer—maybe only hundreds, but very small groups with a shared identity are often called ethnic groups (see Chapter 9). Because Americans control the territory that is the United States, we live in a special kind of country called a nation-state. France and Japan are also good examples of nation-states because almost all of their residents are either French or Japanese, respectively. (Source: p. 136 Graves 2017.)

Because the degree to which people living in a country sense inclusion in a nation varies, a variety of political systems have evolved to ensure some measure of stability in a variety of settings. In places like Egypt, France, and Japan, where nationalist feelings are strong and a national identity is very widely shared, a unitary state generally develops. Unitary state systems generally work best where there is no strong opposition to central control. Therefore, the political elite in a capital city (like Paris or Tokyo) frequently have outsized power over the rest of the country. People living in outlying areas generally acquiesce to the power of the central authority. Fighting between central government and local governments is minimal, and the power of local (provincial) governments is relatively weak.

Many countries have a limited sense of nationhood or perhaps multiple national identities, and therefore those countries are better suited to use a federalist style of government where power is geographically distributed among multiple subnational units. This style of governance makes sense when a country is “young”—and is still in the process of nation-building or developing a common identity necessary for the establishment of a unified nationality. Federations, as these kinds of governments are called, may also work best when the country is multiethnic or multinational. Rather than break into multiple, smaller nation-states, a country can choose to give each of its ethnicities or nationalities some measure of political autonomy. If they want to speak their language or teach their specific religion in the local schools, then the central government allows local people to make those decisions. Federal-style governments leave the central government to focus on things like national defense, managing interstate transportation, regulating a common currency, and promoting the common economy. The US began as a federalist system but is no longer.

Occasionally, a troublesome provincial region or ethnicity will demand special treatment, even in a unitary system. This need arises if the ethnicity is feeling marginalized by the government. For example, in Canada, the French in Quebec province felt that the Canadian government was trying to eliminate their French heritage. The government in Quebec threatened to withdraw from Canada to retain their French culture without interference from the rest of the English culture of Canada. In another example, China has a unitary system, but Hong Kong, a province, operates under a different set of rules than the other provinces. In the United States, Puerto Rico has such a status and therefore is said to have semi-autonomy. There are many dozens of other similarly self-governing regions and territories around the globe. Generally, they are found in the margins of a country’s border.

The United States has had an exceptionally difficult time resolving whether it wants to pursue a unitary or federal-style government. This question has been one of the central political issues in the US since even before the War for Independence. Originally, the United States was organized as a confederation—a loosely allied group of independent states united in a common goal to defeat the British. Operating under the Articles of Confederation from roughly 1776 to 1789, the new and decentralized country found itself challenged to do simple things like raise taxes, sign treaties with foreign countries, or print a common currency because the central government (Congress) was so very weak. The Constitution that the US Government operates under today was adopted to help create a balance of powers between the central government headquartered in Washington, DC, and the multiple state governments. Initially, states continued to operate essentially as separate countries. This is why, in the United States, the word state is used to designate major subnational government units, rather than the word province as is common in much of the world. In our early history, Americans thought, essentially, they were living in “The United Countries of America.” (Source: 137-138 Graves 2017.)

The solidarity and unity of a state are influenced by both centripetal and centrifugal forces. Centripetal forces tend to bind a state together, and centrifugal forces act to break up a state. Examples of centripetal forces include nationalism, economic prosperity, and strong security forces. Centrifugal forces include wars, ineffective or corrupt governments, market failure, and political party discord. Other factors that can influence the solidarity of a state include types of boundaries, ethnic differences (which may result in unity or discord), and the compactness of a state. Local examples include LSU and Saint football, festivals, and crawfish boils.

8.5 The Shape of States

While not the only factor in determining the political landscape, the shape of a state is important because it helps determine potential communication internally, military protection, access to resources, and more. Shape impacts are scalable as demonstrated in these descriptions.

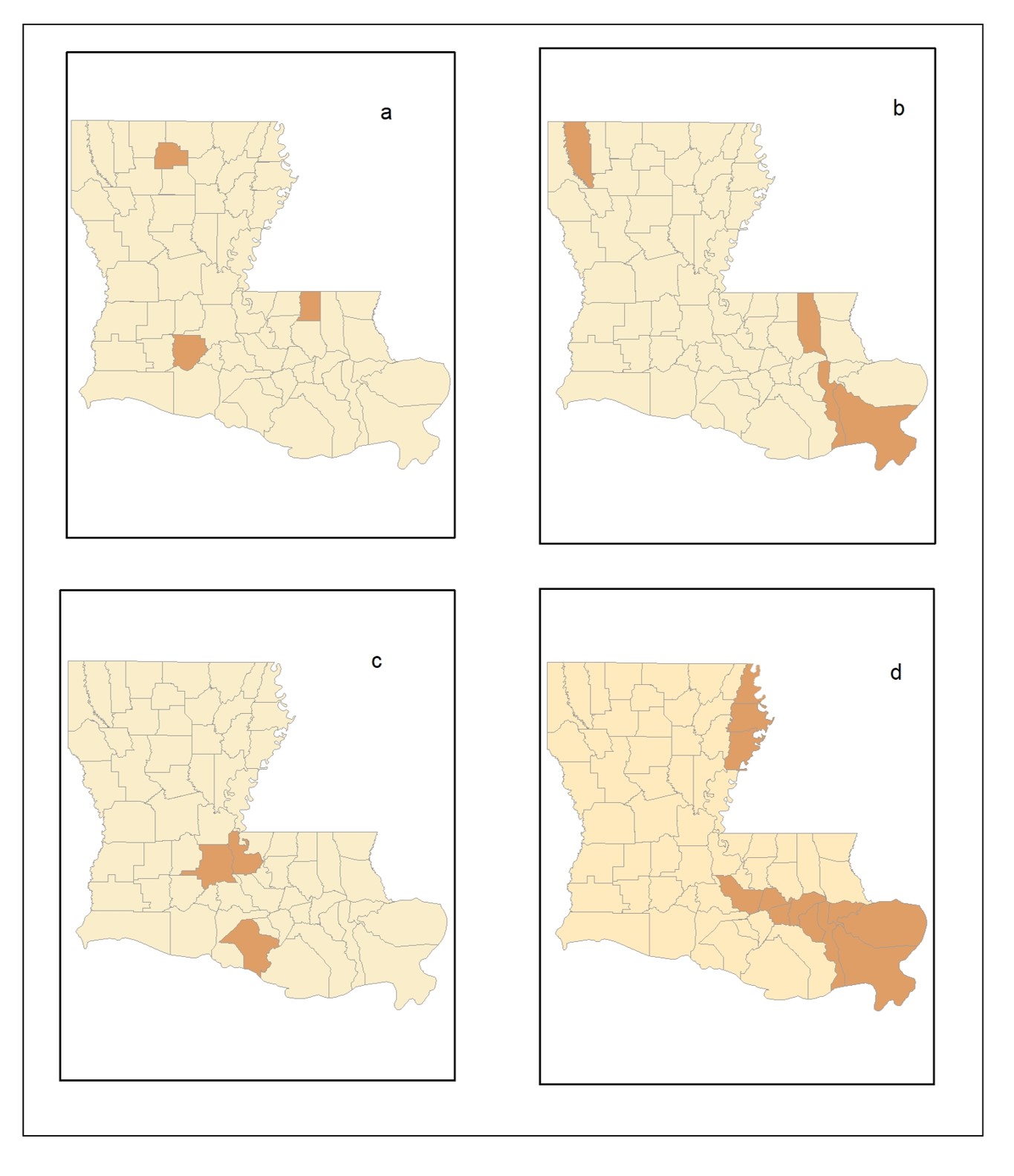

- Compact states have relatively equal distances from their center to any boundary, much like a circle. They are often regarded as efficient states. An example of a compact state would be Kenya. A compact state is ideally circular, where the distance from the center to any border is roughly equal. Ideally, the capital of the state is in the middle and everywhere can be reached in minimal time. Compact borders tend to be easier to defend, and infrastructure costs are less if everything works out of the center. The costs of running a compact state assume that the topography within the boundaries is identical. Louisiana examples of compact parishes include St. Helena, Lincoln, and Acadia parishes (Figure 8.5 a).

- Elongated states have a long and narrow shape. The major problem with these states is internal communication, which causes the isolation of towns from the capital city. Vietnam is an example of this. Louisiana has several elongated parishes; they include Plaquemines, Jefferson, Tangipahoa, and Bossier parishes (Figure 8.5 b).

- Prorupted states occur when a compact state has a portion of its boundary extending outward exceedingly more than the other portions of the boundary. Some of these types of states exist so that the citizens can have access to a specific resource, such as a large body of water. In other circumstances, the extended boundary was created to separate two other nations from having a common boundary. An example of a prorupted state would be Namibia. In Louisiana St. Landry, St. Mary, and Pointe Coupee are excellent examples of prorupted parishes (Figure 8.5 c).

- Perforated states have other state territories or states within them. A great example of this is Lesotho, which is a sovereign state within South Africa. There are no perforated parishes in Louisiana.

- Fragmented states exist when a state is separated. Sometimes large bodies of water can fragment a state. Indonesia is an example of a fragmented state. Indonesia consists of over 17,000 islands, and to increase the solidarity of the State, the government actively encouraged migration to less populated islands to assimilate indigenous populations and decrease population pressures on the most populous island. In the Philippines, another fragmented state, control of its southern islands such as Mindanao is problematic because of terrorist groups that are active in those areas. Transportation of products to and from the market in a fragmented state is much more expensive and difficult to maintain. There are many more borders to deal with, and they can be difficult to unite because of the relative isolation of each part. The Mississippi River bisects several eastern parishes. In the northeast, portions of West Carroll, Madison, and Tensas all are found on both the west and east sides of the Mississippi River. Further south, the Mississippi River flows through Iberville to Plaquemines parishes. Additionally, many of the coastal parishes are fragmented; examples include St. Martin, Iberia, and St. Bernard (Figure 8.5 d).

- Landlocked states lack a direct outlet to a major body of water, such as a sea or ocean. This becomes problematic specifically for exporting trade and can hinder a state’s economy. Landlocked states are most common in Africa, where the European powers divided up Africa into territories during the Berlin Conference of 1884. After these African territories gained their independence and broke into sovereign states, many became landlocked from the surrounding ocean. An example here would be Uganda. As can be seen in Figure 8.5, many parishes in Louisiana are landlocked.

8.6 Supranational Organizations—COOPERATION BETWEEN STATES

To provide shared military and economic security as a unified entity, states engage in alliances. Military alliances help protect states from common enemies, and economic alliances allow for the free exchange of goods in a larger market. These alliances are also referred to as supranational organizations, and they all involve states giving up some of their sovereign power for the common good.

The largest supranational organization in the world is the United Nations (UN). Formed originally as the League of Nations after World War II, the UN now includes 193 states. The work of the UN includes peacekeeping, humanitarian relief, and the establishment of internationally approved standards of behavior. The headquarters of the UN is in New York City, and important subsidiary organizations of the UN include the World Health Organization (WHO), UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Cultural and Cultural Organization), and the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). Other important supranational organizations that are more regional include OPEC (Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries), MERCOSUR (Southern Common Market/Mercado Común del Sur), AU (African Union), and ASEAN (Association of Southeast Asian Nations).

8.6.1 Military Alliances—NATO and Warsaw Pact

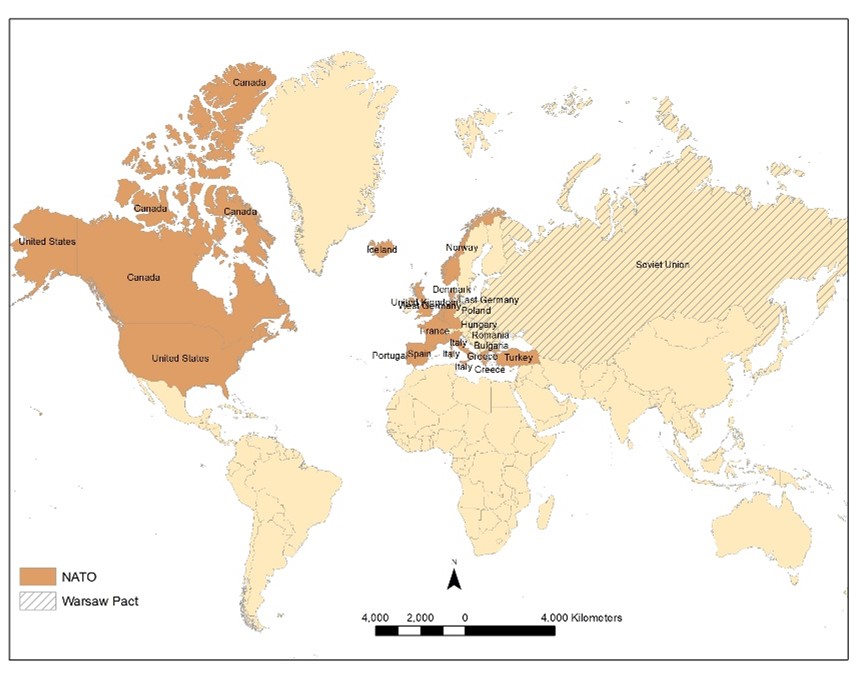

In terms of military alliances on a regional scale, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) comprises 30 states and was developed after World War II to counter the threat of the former Soviet Union. Member states include numerous Western European states as well as the United States and Canada (Figure 8.6).

When the Soviet Union existed, the Warsaw Pact was a military alliance between the Soviet Union and seven satellite states of Eastern and Central Europe (Figure 8.6). The Warsaw Pact disbanded in 1991, and several of the former Soviet states as well as satellite states have subsequently joined NATO. As a result, Russia has felt isolated and vulnerable and has been aggressively acting to seize or control territories in states close to its borders.

For example, in 2008, Russia engaged in a military conflict in Georgia, one of the former Soviet Union’s states, to support a separatist movement allied with Russia. In 2014, Russia invaded the peninsula of Crimea, within the territorial boundaries of Ukraine, one of the former states in the Soviet Union. Furthermore, Russia has intervened militarily against the rebel forces fighting in eastern Ukraine. In response to these provocations, NATO commenced Operation Atlantic Resolve, an ongoing series of training exercises between the United States and other NATO countries in former Warsaw Pact countries such as Poland, Romania, and Latvia.

8.6.2 Military Alliances—Terrorism

Although terrorists are characterized as non-military, non-state actors, they have a tremendous impact on states around the world and involve allied groups in many countries. Terrorism is the intimidation of a population by violence to further political aims. The first terrorist group with global influence is Al Qaeda, formed in 1988 by Osama bin Laden. Although its influence has waned in the past decade, Al Qaeda was responsible for the 9/11 attacks and had several affiliates including Boko Haram in Nigeria and Abu Sayyaf in the Philippines. With the rise of the Islamic State (ISIS/L) in Iraq and Syria in 2013, terrorist groups such as Boko Haram and Abu Sayyaf have consequently declared allegiance to ISIS/L. ISIS/L is an extremist Muslim group that intends to seize as much territory as possible in the Middle East and force its subjects to adhere to their strict version of Islamic fundamentalism. To facilitate their goal, ISIS/L conducts an extensive campaign on social media to recruit fighters to come to Syria and also conduct individual attacks in their home country. Their media campaign has been successful in recruiting numerous militants to come to Syria and to inspire or instigate attacks in the United States, France, Belgium, England, Sweden, Turkey, Afghanistan, Yemen, and Saudi Arabia (Figure 8.7). Furthermore, ISIS/L is conducting regular military operations in Libya and Egypt.

To combat the Islamic State and other terrorist groups, interesting military alliances have developed, and the situation is exceptionally complex. The United States cooperates with numerous NATO allies to train and equip local military forces in Iraq and Syria. Iran, in alliance with Iraq, has assisted in driving ISIS/L out of Iraq. Kurdish forces in northern Iraq and Syria, in concert with NATO forces, have conducted much of the military action, and they hope for an independent state because of these efforts. Complicating this situation is the objection of the central governments of Iraq, Syria, and Turkey to an independent Kurdish state. Further clouding the situation is the alliance between Russia and the Syrian central government. Although these two countries do fight against ISIS/L, they are also opposed to other Syrian rebel forces, which the United States supports. The problem of ISIS/L propaganda is being addressed by numerous governments and social media outlets such as Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube. More importantly, though, military success on the ground against ISIS/L forces in Iraq and Syria is decreasing the influx of foreign fighters as well as the proliferation of internet propaganda.

8.6.3 Economic Alliances—European Union and USMCA

One of the most prominent economic alliances in the world is the European Union (EU), which consists of 27 member states (Figure 8.8). What began as the European Community (EC) in 1958, the European Union has grown significantly from the original six members and now includes seven Eastern European states that were formerly in the Soviet Union. The EU has developed a common currency, the euro, for all member countries and a European Central Bank. Furthermore, at most boundaries, a passport is not required to enter another country.

One of the weaknesses of the EU is the need to subsidize poorer countries, creating financial difficulties for the more wealthy members. For example, Greece has experienced large debts that have required rescue funding from the EU. Another issue confronting the EU is whether or not to allow Turkey to join, as Greece has long-standing disputes with Turkey over territory in Cyprus, and the Turkish central government has been accused of anti-democratic practices. Perhaps most concerning for the EU is the departure of the United Kingdom (UK) from the alliance in an action termed “Brexit.” In 2016, the UK voted by referendum to leave the EU. The UK’s decision to leave the EU is not solely related to economics, as not only is the EU an economic alliance, but agreements on social and political policies are involved as well. The majority of British citizens are generally against the subsidizing of poorer states and the increasing number of immigrants who use scarce public resources, and they generally desire greater autonomy. With the exit of Britain from the EU, EU members are concerned that other states may follow suit.

An important economic alliance for the United States is the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA), formerly known as the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). Established in 1992, this alliance integrates the United States, Mexico, and Canada and facilitates the flow of goods and services across borders.

8.7 BOUNDARIES AND BOUNDARY DISPUTES

“Good fences make good neighbors.”

-Robert Frost

Boundaries can influence the solidarity of a state, as boundary disputes can result in conflict. Boundaries = territoriality section. A boundary is essentially an invisible, vertical plane that separates one state from another, so it includes both the airspace above the line on the surface and the ground below. Boundaries can be both physical and anthropogenic, and while it is difficult to categorize all boundaries, some prominent boundary types exist.

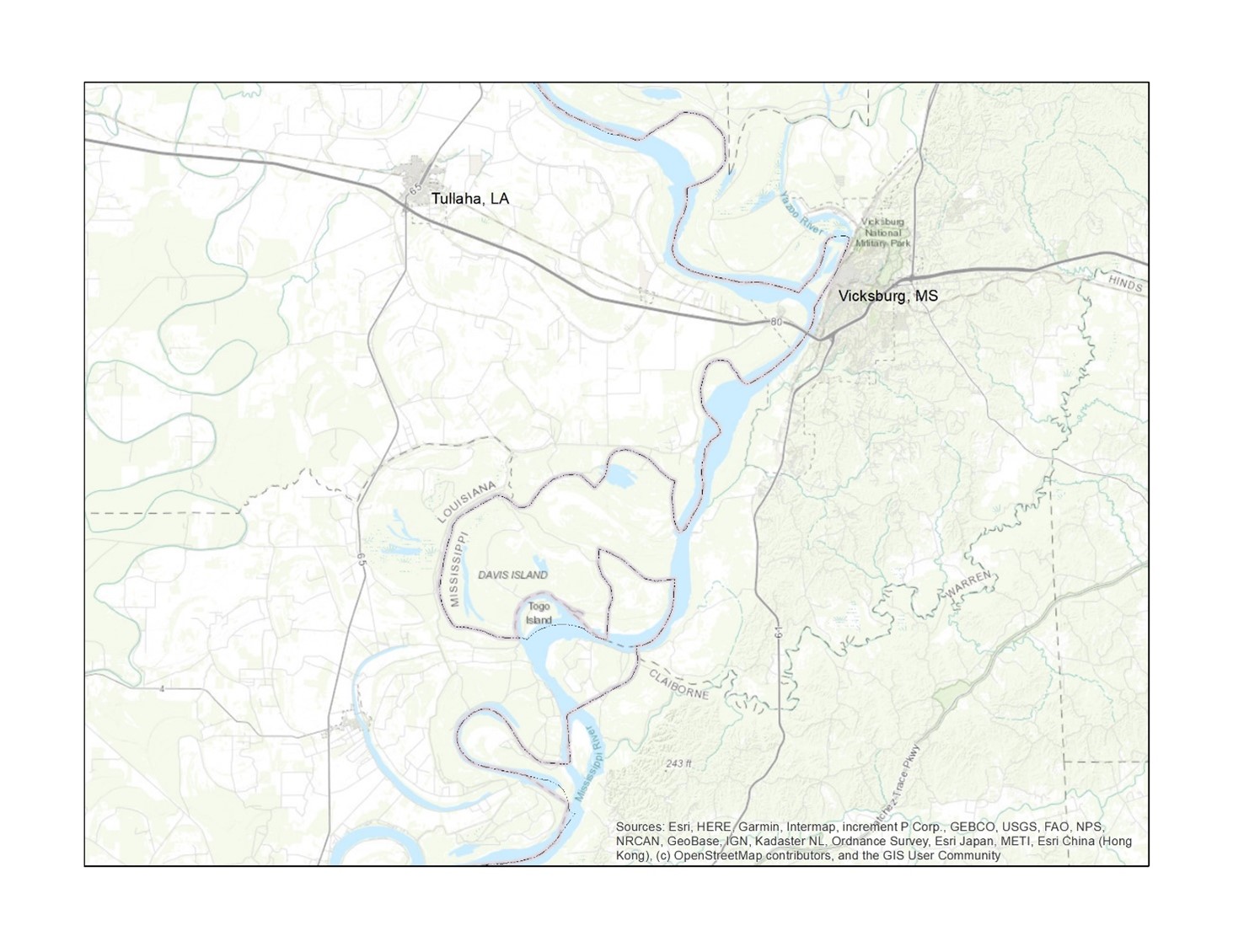

Physical boundaries are natural features on the landscape such as rivers, lakes, and mountains. The Rio Grande is an important physical boundary on the southern border of the United States. Major rivers serve as natural boundaries in Louisiana. The Mississippi and Pearl Rivers are the northeast and southeast boundary, respectively, with Mississippi, while the Sabine River is one of our western borders with Texas. Like most rivers, the Rio Grande shifts gradually (and sometimes abruptly) through time. As a result of the fact that the course of a river is not fixed, a river boundary can be problematic. The ever-shifting Mississippi River has historically posed problems with the Louisiana-Mississippi Border. Davis Island is one such example. The island is located on the west side of the Mississippi River but belongs to the State of Mississippi (Figure 8.9). Some examples of mountain ranges as boundaries include the Zagros Mountains between Iraq and Iran, the Pyrenees between Spain and France, and the Andes Mountains between Chile and Argentina.

In contrast to physical boundaries, geometric boundaries, and ethnic boundaries are not related to natural features. Instead, in the case of geometric boundaries, they are straight lines. These straight lines could coincide with latitude or longitude, as is the case with the northwestern boundary of the United States with Canada along 49 degrees north latitude. Likewise, Indonesia and Papua New Guinea are separated by another geometric boundary along the 141st meridian. Louisiana’s northern borders (33 and 31 degrees north latitude) are excellent examples of geometric boundaries.

For ethnic boundaries, they are drawn based on a cultural trait, such as where people share a language or religion. The border between India, which is predominantly Hindu, and Pakistan, which is predominantly Muslim, is one example. Some borders split ethnic groups that are more closely related to the people on the other side of the border. For example, in eastern Ukraine, the majority of the population speaks Russian and is sympathetic to Russians on the other side of the border. As a result, the current conflict between Russia and Ukraine has been problematic for the Ukrainian central government because of the Russian affiliation with eastern Ukraine. Russian influence in eastern Ukraine is an example of irredentism, or an effort to expand the political influence of a state on a group of people in a neighboring state.

Another prime example of where boundaries do not coincide closely with ethnic groups is in Africa. Almost 50 percent of the boundaries in Africa are geometric, and at least 177 ethnic groups are split into two or more states. If all ethnic groups in Africa were to be enclosed in their boundaries, Africa would have over 2,000 countries (1). Because ethnic groups straddle many boundaries in Africa, this situation has led to considerable cross-border trade but also has created numerous conflicts. For instance, several wars have occurred because the Somali ethnic group is split between five different countries.

8.8 US ELECTORAL GEOGRAPHY

8.8.1 Presidential Elections

One of the more intriguing aspects of political geography in the United States is presidential elections and how the Electoral College process has a decidedly spatial component. An examination of presidential election results reveals interesting regional affiliations (Figures 8.10 & 8.11). Northeastern and Mid-Atlantic states, as well as far Western states, all tended to vote Democrat, while much of the remaining electoral map is Republican. Although it appears that the Republican victory in 2016 was decisive from a spatial and Electoral College perspective, from the standpoint of the popular vote, the Democratic candidate earned several million more votes than the Republican candidate. The electoral college system forces candidates to spend disproportionate amounts of time and resources in a handful of competitive and often smaller, less vote-rich states—often called “swing states.”

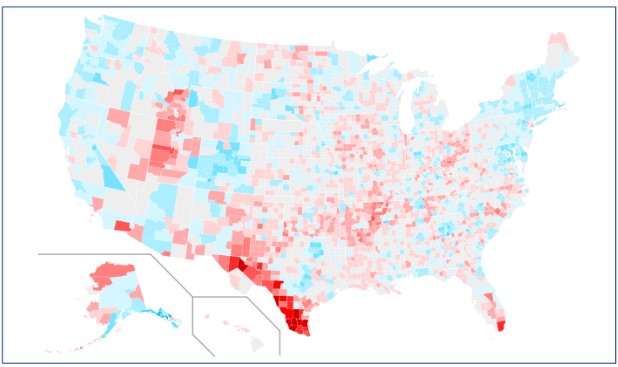

Examining presidential election results at the county scale, rather than at the statewide scale, illustrates other important patterns. While a glance at Figure 8.12 might make you think the United States is dominated by the Republican Party, evidenced by a sea of red interspersed with blue archipelagos, it is important to note that while land does not vote, people do—and people belonging to certain ethnic and educational groups tend to vote in particular voting blocs. While voters historically have often been polarized by race, over the last decade, voters in the United States have also become increasingly polarized by educational status. Those with a college degree, and the counties where they are highly concentrated, increasingly favor the Democratic Party. Those without a college degree, and the counties where they are highly concentrated, increasingly favor the Republican Party.

Under current partisan coalitions, the Democratic Party tends to dominate in voter-rich urban and suburban areas with high concentrations of minority voters and college-educated white voters. On the other hand, the Republican Party, once anchored by affluent, white, and highly educated suburban areas, has seen its coalition become much more dependent on sparsely-populated and formerly more competitive rural areas as the suburbs trend towards Democrats. These areas, especially apparent in the Great Plains, Mountain West, and Appalachian regions, tend to contain high concentrations of non-college-educated white voters and low concentrations of minority voters. Success for the Democratic Party in rural areas, like the Mississippi Delta region of Louisiana and Mississippi, and scattered counties in states like Arizona and South Dakota, is often driven by support among rural minority voters (in these cases, by African Americans and Native American voters, respectively). Other rural areas that have retained Democratic support, like those in northeastern Minnesota and New England, often feature rich traditions of labor organizing and/or higher shares of college-educated voters.

Though Americans have become more polarized by educational status at the polls, polarization by race eased between the 2016 and 2020 presidential elections. Figure 8.13 shows county-level swings between 2016 and 2020—in which counties with an increasing share of votes for Democrats are shaded in blue and counties with an increasing share of voters for Republicans are shaded in red. While white voters tend to support Republican candidates and minority voters tend to support Democratic candidates (with Black voters often supporting Democratic candidates with over 90% of their votes), the Democratic Party improved upon its share of white voters. Two notable exceptions are seen in Arkansas and areas of the Mountain West with high shares of Mormon voters. The Democratic nominee in 2016 was formerly the First Lady of Arkansas and performed better than her 2020 successor. In Utah and Idaho, many typically Republican Mormon voters uncomfortable with their nominee turned to an independent candidate from their faith in 2016—but ultimately fell in line behind their party’s nominee in 2020. At the same time, the Republican Party improved upon its share of minority voters—especially apparent in Black, Hispanic, and Asian communities of major metropolitan areas like New York City, Los Angeles, and Miami and Texas’ more rural and heavily Hispanic Rio Grande Valley region.

8.8.2 Gerrymandering

At the 2019 annual meeting of the American Association of Geographers, former United States Attorney General Eric Holder used his keynote address to call for geographers to engage with electoral politics more comprehensively—especially in the areas of redistricting and gerrymandering. In the United States, boundaries play an important role in the electoral process, but in this case, district and precinct boundaries are significant in contrast to the country boundaries that have been previously discussed. After each decennial census, state and local governments redraw their district lines to adjust to updated population figures. In most states, including Louisiana, redistricting is conducted by politically partisan elected officials, like governors and state legislators. Political parties in power during redistricting processes often rearrange the boundaries of voting districts to benefit themselves electorally. This practice is called gerrymandering.

The term gerrymandering originates in Massachusetts’ 1812 state legislative redistricting process. The state’s governor, Elbridge Gerry, supported a plan to draw State Senate districts in meandering shapes that advantaged his political party—the Democratic-Republicans (McGann, 2016). In response, the Salem Gazette published a political cartoon, seen in Figure 8.14, that depicted one particularly outlandish district north of Boston as a winged and taloned salamander-like creature. The word “gerrymander,” originally appearing as “Gerry-mander,” is simply a portmanteau of the governor’s last name and “salamander.” Like in early 1800s Massachusetts, bizarrely shaped gerrymandered districts continue to receive media and public scorn.

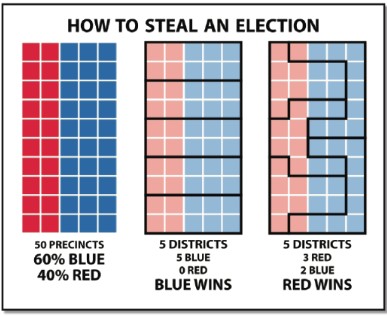

The two most common gerrymandering strategies are called “packing” and “cracking.” A “packed” district is drawn to contain a very high concentration of voters from an opposing party or group. As US elections are generally “first-past-the-post,” this means that voters above the winning simple majority threshold effectively waste their votes—winning a district with 51% of the vote yields the same victory as a win with 70% of the vote and dilutes that party’s or group’s overall voting power. A “cracked” district is drawn to split voters from an opposing party or group between multiple districts, also diluting their voting power and effectively preventing them from building a winning majority in any. Like in early 1800s Massachusetts, bizarrely shaped gerrymandered districts continue to receive media and public scorn. The basic anatomy of gerrymandering is illustrated below in Figure 8.15.

While gerrymandering for partisan reasons is not generally illegal in the United States, gerrymandering can be challenged in court when it appears to discriminate against minority populations. Complicating matters is the fact that race and partisanship are deeply intertwined in the United States. This is especially true in southern states like Louisiana. In Louisiana, Republican candidates frequently earn the support of over 80% of white voters, while Democratic candidates frequently earn the support of over 90% of Black voters. It can be very difficult to determine if the districts in question were drawn to advantage a political group at the expense of another (legal) or to advantage a racial/ethnic group at the expense of another (illegal). Louisiana, like other southern states, has a long history of racial discrimination in voting. Until the Supreme Court’s decision in Shelby County v. Holder (2013), changes to voting and election procedures in Louisiana and other states with similar histories were subject to a federal approval process under the Voting Rights Act of 1965 to ensure they did not have discriminatory intent or effect.

Currently, though Black residents make up roughly one-third of Louisiana’s population, they only constitute a majority in one of the state’s six congressional districts. This has often been cited by residents and civil rights groups as discriminatory because, in the state’s other five congressional districts, Black voters do not have an opportunity to elect candidates of their choice. They argue that their one-third share of the population should be reflected in the one-third share of the state’s congressional seats. In partisan terms, though Democratic presidential candidates often earn around two-fifths of the vote statewide, the party only sees success in one-sixth of the state’s congressional districts. In effect, many Black voters, who typically support Democratic candidates, are packed into a single district (LA-2), while the remaining Black voters are split amongst the state’s other five districts. This same disparity is also seen in the state’s other kinds of electoral districts—including those for the state legislature and the Board of Elementary and Secondary Education (BESE). A map of Louisiana’s congressional districts, instituted in 2022, is seen below in Figure 8.16.

8.9 KEY TERMS DEFINED

Balkanization: refers to any country that breaks apart to form several states, usually as a consequence of civil war or ethnic cleansing.

Boundary: an invisible, vertical plane that separates one state from another, which includes both the airspace above the line on the surface and the ground below.

Centripetal force: a force that tends to bind a state together.

Centrifugal force: a force that tends to break a state apart.

Compact state: a state where the distance from the center to any border does not vary significantly; roughly circular.

Elongated state: a state that has a long and narrow shape.

Ethnic boundary: a boundary that encompasses a particular ethnic group.

Fragmented state: a state whose territory is not contiguous but consists of isolated parts such as islands.

Geometric boundary: a boundary that follows a straight line and may coincide with a line of latitude or longitude.

Gerrymandering: the process of redrawing legislative districts to benefit the party in power and ensure victory in elections.

Irredentism: an effort to expand the political influence of a state on a group of people in a neighboring state.

Landlocked state: a state that lacks a direct outlet to a major body of water, such as a sea or ocean.

Multinational state: the state that has more than one nation within its borders.

Nation: a group of people bonded by cultural attributes such as language, ethnicity, and religion.

Nation-state: a state in which the territorial boundaries encompass a group of people with a shared ethnicity.

Perforated state: a state that has another other state territories or states within them.

Physical boundary: a boundary that follows a natural feature on the landscape such as a river, mountain range, or lake.

Political geography: the study of how humans have divided up the surface of the Earth for purposes of management and control.

Prorupted state: a compact state that has a portion of its boundary extending outward exceedingly more than the other portions of the boundary.

State: a formal region in which the government has sovereignty or control of its affairs within its territorial boundaries.

Stateless nation: a nation that aspires to become a nation-state but does not yet have its territory.

Supranational organization: an alliance involving three or more states that have shared objectives that may be economic, political/military, or cultural.

Terrorism: intimidation of a population by violence to further political aims.

Territoriality: the establishment of the rules governing a space.

8.10 WORKS CONSULTED AND FURTHER READING

Acemoglu, Daron, and James A. Robinson. 2013. Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty. Reprint edition. New York: Currency.

Flint, Colin, and Peter Taylor. 2011. Political Geography: World-Economy, Nation-State, and Locality. 6th edition. London; New York: Routledge.

Frost, Robert. “Mending Wall by Robert Frost.” Poetry Foundation. Accessed April 30, 2018. https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/44266/mending-wall.

Gallaher, Carolyn, Carl T. Dahlman, Mary Gilmartin, Alison Mountz, and Peter Shirlow. 2009. Key Concepts in Political Geography. 1st edition. London; Los Angeles: SAGE Publications Ltd.

Glassner, Martin Ira, and Chuck Fahrer. 2003. Political Geography. 3rd edition. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons.

Graves, Steven. 2017. Introduction to Human Geography: A Disciplinary Approach. https://sites.google.com/site/gravesgeography/introduction-to-human-geography

Jones, Martin, Rhys Jones, Michael Woods, Mark Whitehead, Deborah Dixon, and Matthew Hannah. 2015. An Introduction to Political Geography: Space, Place and Politics. 2nd edition. London; New York: Routledge.

Mann, Michael. 2012. The Sources of Social Power: Volume 1; A History of Power from the Beginning to AD 1760. 2nd edition. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Marshall, Tim. 2015. Prisoners of Geography: Ten Maps That Explain Everything about the World. 1st edition. New York: Scribner.

Mungai, Christine. “Africa’s Borders Split over 177 Ethnic Groups, and Their ‘Real’ Lines Aren’t Where You Think.” MG Africa. January 13, 2015. Accessed April 30, 2018. http://mgafrica.com/article/2015-01-09-africas-real-borders-are-not-whereyou-think.

Painter, Joe, and Alex Jeffrey. 2009. Political Geography. 2nd edition. Los Angeles: SAGE Publications Ltd.

Rosenfeld, Christine, and Nathan Burtch. (No Date). Human Geography. https://pressbooks.pub/humangeog/

8.11 ENDNOTES

- Adapted from https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2015/06/17/world/middleeast/ map-isis-attacks-around-the-world.html