168 Introduction

Paul Flowers; Edward J. Neth; William R. Robinson; Klaus Theopold; and Richard Langley

[latexpage]

Learning Objectives

- Chemical Equilibria

- Equilibrium Constants

- Shifting Equilibria: Le Châtelier’s Principle

- Equilibrium Calculations

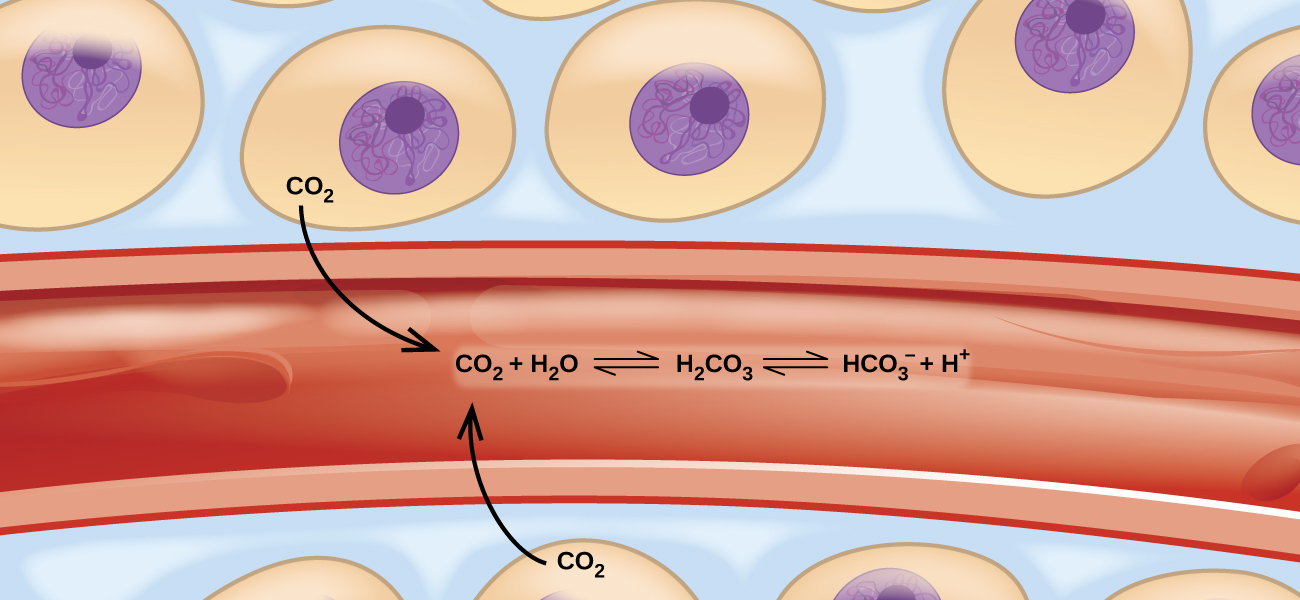

Imagine a beach populated with sunbathers and swimmers. As those basking in the sun get too hot, they enter the surf to swim and cool off. As the swimmers tire, they return to the beach to rest. If the rate at which sunbathers enter the surf were to equal the rate at which swimmers return to the sand, then the numbers (though not the identities) of sunbathers and swimmers would remain constant. This scenario illustrates a dynamic phenomenon known as equilibrium, in which opposing processes occur at equal rates. Chemical and physical processes are subject to this phenomenon; these processes are at equilibrium when the forward and reverse reaction rates are equal. Equilibrium systems are pervasive in nature; the various reactions involving carbon dioxide dissolved in blood are examples (see (Figure)). This chapter provides a thorough introduction to the essential aspects of chemical equilibria.

We now have a good understanding of chemical and physical change that allow us to determine, for any given process:

- Whether the process is endothermic or exothermic

- Whether the process is accompanied by an increase of decrease in entropy

- Whether a process will be spontaneous, non-spontaneous, or what we have called an equilibrium process

Recall that when the value ∆G for a reaction is zero, we consider there to be no free energy change—that is, no free energy available to do useful work. Does this mean a reaction where ΔG = 0 comes to a complete halt? No, it does not. Just as a liquid exists in equilibrium with its vapor in a closed container, where the rates of evaporation and condensation are equal, there is a connection to the state of equilibrium for a phase change or a chemical reaction. That is, at equilibrium, the forward and reverse rates of reaction are equal. We will develop that concept and extend it to a relationship between equilibrium and free energy later in this chapter.

In the explanation that follows, we will use the term Q to refer to any reactant or product concentration or pressure. When the concentrations or pressure of reactants and products are at equilibrium, the term K will be used. This will be more clearly explained as we go along in this chapter.

Now we will consider the connection between the free energy change and the equilibrium constant. The fundamental relationship is:

\(∆G°=\mathrm{-R}T\text{ln}K\)—this can be for \({K}_{c}\) or \({K}_{p}\) (and we will see later, any equilibrium constant we encounter).

We also know that the form of K can be used in non-equilibrium conditions as the reaction quotient, Q. The defining relationship here is

Without the superscript, the value of ∆G can be calculated for any set of concentrations.

Note that since Q is a mass-action reaction of productions/reactants, as a reaction proceeds from left to right, product concentrations increase as reactant concentrations decrease, until Q = K, and at which time ∆G becomes zero:

\(0=∆G°+RT\text{ln}K\), a relationship that reduces to our defining connection between Q and K.

Thus, we can see clearly that as a reaction moves toward equilibrium, the value of ∆G goes to zero.

Now, think back to the connection between the signs of ∆G° and ∆H°

| ∆H° | ∆S° | Result |

| Negative | Positive | Always spontaneous |

| Positive | Negative | Never spontaneous |

| Positive | Positive | Spontaneous at high temperatures |

| Negative | Negative | Spontaneous at low temperatures |

Only in the last two cases is there a point at which the process swings from spontaneous to non-spontaneous (or the reverse); in these cases, the process must pass through equilibrium when the change occurs. The concept of the connection between the free energy change and the equilibrium constant is an important one that we will expand upon in future sections. The fact that the change in free energy for an equilibrium process is zero, and that displacement of a process from that zero point results in a drive to re-establish equilibrium is fundamental to understanding the behavior of chemical reactions and phase changes.