Chapter 2: Limits and The Derivative

Introduction to Limits

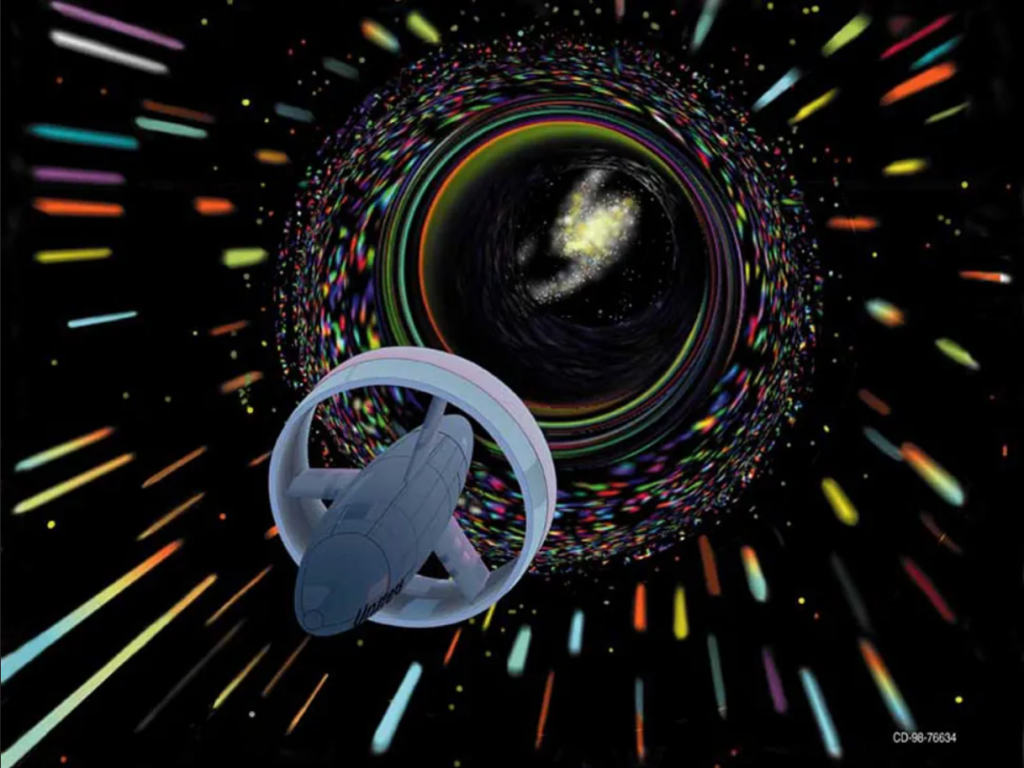

Science fiction writers often imagine spaceships that can travel to far-off planets in distant galaxies. However, in 1905, Albert Einstein showed that a limit exists on how fast any object can travel. The problem is that the faster an object moves, the more mass it attains (in the form of energy), according to the equation

where [latex]m_0[/latex] is the object’s mass at rest, [latex]v[/latex] is its speed, and [latex]c[/latex] is the speed of light. What is this speed limit? (See “Chapter Opener: Einstein’s Equation” Example in Section 2.1: Limits.)

The idea of a limit is central to all of calculus. We begin this chapter by examining why limits are so important. Then we go on to describe how to find the limit of a function at a given point. Not all functions have limits at all points, and we discuss what this means and how we can tell if a function does or does not have a limit at a particular value. This chapter has been created in an informal, intuitive fashion.

Introduction from Calculus, Volume 1, by Strang and Herman, OpenStax (Web), licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 License.

Media Attributions

- Chapter 2 Introduction Figure © OpenStax Calculus Volume 1 is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license