55 ATP: Adenosine Triphosphate

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to do the following:

- Explain ATP’s role as the cellular energy currency

- Describe how energy releases through ATP hydrolysis

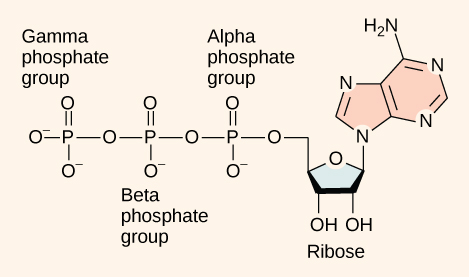

Even exergonic, energy-releasing reactions require a small amount of activation energy in order to proceed. However, consider endergonic reactions, which require much more energy input, because their products have more free energy than their reactants. Within the cell, from where does energy to power such reactions come? The answer lies with an energy-supplying molecule scientists call adenosine triphosphate, or ATP. This is a small, relatively simple molecule (Figure 6.13), but within some of its bonds, it contains the potential for a quick burst of energy that can be harnessed to perform cellular work. Think of this molecule as the cells’ primary energy currency in much the same way that money is the currency that people exchange for things they need. ATP powers the majority of energy-requiring cellular reactions.

As its name suggests, adenosine triphosphate is comprised of adenosine bound to three phosphate groups (Figure 6.13). Adenosine is a nucleoside consisting of the nitrogenous base adenine and a five-carbon sugar, ribose. The three phosphate groups, in order of closest to furthest from the ribose sugar, are alpha, beta, and gamma. Together, these chemical groups constitute an energy powerhouse. However, not all bonds within this molecule exist in a particularly high-energy state. Both bonds that link the phosphates are equally high-energy bonds (phosphoanhydride bonds) that, when broken, release sufficient energy to power a variety of cellular reactions and processes. These high-energy bonds are the bonds between the second and third (or beta and gamma) phosphate groups and between the first and second phosphate groups. These bonds are “high-energy” because the products of such bond breaking—adenosine diphosphate (ADP) and one inorganic phosphate group (Pi)—have considerably lower free energy than the reactants: ATP and a water molecule. Because this reaction takes place using a water molecule, it is a hydrolysis reaction. In other words, ATP hydrolyzes into ADP in the following reaction:

ATP+H2O→ADP+Pi+free energy

Like most chemical reactions, ATP to ADP hydrolysis is reversible. The reverse reaction regenerates ATP from ADP + Pi. Cells rely on ATP regeneration just as people rely on regenerating spent money through some sort of income. Since ATP hydrolysis releases energy, ATP regeneration must require an input of free energy. This equation expresses ATP formation:

ADP+Pi+free energy→ATP+H2O

Two prominent questions remain with regard to using ATP as an energy source. Exactly how much free energy releases with ATP hydrolysis, and how does that free energy do cellular work? The calculated ∆G for the hydrolysis of one ATP mole into ADP and Pi is −7.3 kcal/mole (−30.5 kJ/mol). Since this calculation is true under standard conditions, one would expect a different value exists under cellular conditions. In fact, the ∆G for one ATP mole’s hydrolysis in a living cell is almost double the value at standard conditions: −14 kcal/mol (−57 kJ/mol).

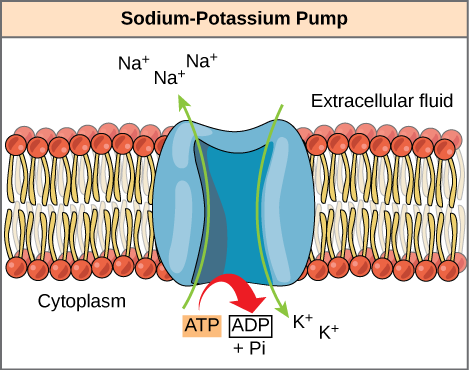

ATP is a highly unstable molecule. Unless quickly used to perform work, ATP spontaneously dissociates into ADP + Pi, and the free energy released during this process is lost as heat. The second question we posed above discusses how ATP hydrolysis energy release performs work inside the cell. This depends on a strategy scientists call energy coupling. Cells couple the ATP hydrolysis’ exergonic reaction allowing them to proceed. One example of energy coupling using ATP involves a transmembrane ion pump that is extremely important for cellular function. This sodium-potassium pump (Na+/K+ pump) drives sodium out of the cell and potassium into the cell (Figure 6.14). A large percentage of a cell’s ATP powers this pump, because cellular processes bring considerable sodium into the cell and potassium out of it. The pump works constantly to stabilize cellular concentrations of sodium and potassium. In order for the pump to turn one cycle (exporting three Na+ ions and importing two K+ ions), one ATP molecule must hydrolyze. When ATP hydrolyzes, its gamma phosphate does not simply float away, but it actually transfers onto the pump protein. Scientists call this process of a phosphate group binding to a molecule phosphorylation. As with most ATP hydrolysis cases, a phosphate from ATP transfers onto another molecule. In a phosphorylated state, the Na+/K+ pump has more free energy and is triggered to undergo a conformational change. This change allows it to release Na+ to the cell’s outside. It then binds extracellular K+, which, through another conformational change, causes the phosphate to detach from the pump. This phosphate release triggers the K+ to release to the cell’s inside. Essentially, the energy released from the ATP hydrolysis couples with the energy required to power the pump and transport Na+ and K+ ions. ATP performs cellular work using this basic form of energy coupling through phosphorylation.

Visual Connection

Often during cellular metabolic reactions, such as nutrient synthesis and breakdown, certain molecules must alter slightly in their conformation to become substrates for the next step in the reaction series. One example is during the very first steps of cellular respiration, when a sugar glucose molecule breaks down in the process of glycolysis. In the first step, ATP is required to phosphorylate glucose, creating a high-energy but unstable intermediate. This phosphorylation reaction powers a conformational change that allows the phosphorylated glucose molecule to convert to the phosphorylated sugar fructose. Fructose is a necessary intermediate for glycolysis to move forward. Here, ATP hydrolysis’s exergonic reaction couples with the endergonic reaction of converting glucose into a phosphorylated intermediate in the pathway. Once again, the energy released by breaking a phosphate bond within ATP was used for phosphorylyzing another molecule, creating an unstable intermediate and powering an important conformational change.

Link to Learning

See an animation of the ATP-producing glycolysis process at this site.

Glycolysis: An overview at this site.

Steps of glycolysis reactions at this site.

Glycolysis explained (aerobic vs. anaerobic, pyruvate, gluconeogenesis) at this site.

Krebs Cycle at this site.

Cellular respiration: Glycolysis, Krebs Cycle, Electron Transport Chain at this site.