124 Chromosomal Basis of Inherited Disorders

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to do the following:

- Describe how a karyogram is created

- Explain how nondisjunction leads to disorders in chromosome number

- Compare disorders that aneuploidy causes

- Describe how errors in chromosome structure occur through inversions and translocations

Inherited disorders can arise when chromosomes behave abnormally during meiosis. We can divide chromosome disorders into two categories: abnormalities in chromosome number and chromosomal structural rearrangements. Because even small chromosome segments can span many genes, chromosomal disorders are characteristically dramatic and often fatal.

Chromosome Identification

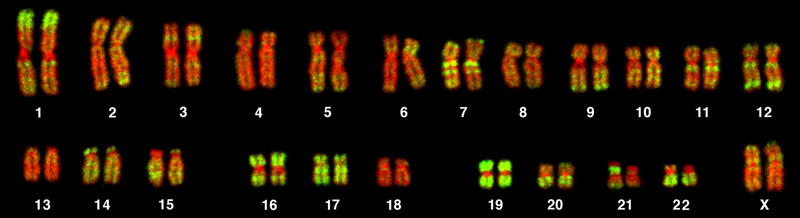

Chromosome isolation and microscopic observation form the basis of cytogenetics and are the primary methods by which clinicians detect chromosomal abnormalities in humans. A karyotype is the number and appearance of chromosomes, and includes their length, banding pattern, and centromere position. To obtain a view of an individual’s karyotype, cytologists photograph the chromosomes and then cut and paste each chromosome into a chart, or karyogram. Another name is an ideogram (Figure 13.5).

In a given species, we can identify chromosomes by their number, size, centromere position, and banding pattern. In a human karyotype, autosomes or “body chromosomes” (all of the non–sex chromosomes) are generally organized in approximate order of size from largest (chromosome 1) to smallest (chromosome 22). The X and Y chromosomes are not autosomes. However, chromosome 21 is actually shorter than chromosome 22. Researchers discovered this after naming Down syndrome as trisomy 21, reflecting how this disorder results from possessing one extra chromosome 21 (three total). Not wanting to change the name of this important disorder, scientists retained the numbering of chromosome 21 despite describing it having the shortest set of chromosomes. We may designate the chromosome “arms” projecting from either end of the centromere as short or long, depending on their relative lengths. We abbreviate the short arm p (for “petite”), whereas we abbreviate the long arm q (because it follows “p” alphabetically). Numbers further subdivide and denote each arm. Using this naming system, we can describe chromosome locations consistently in the scientific literature.

Visual Connection

Geneticists Use Karyotypes to Identify Chromosomal Aberrations

Although we refer to Mendel as the “father of modern genetics,” he performed his experiments with none of the tools that the geneticists of today routinely employ. One such powerful cytological technique is karyotyping, a method in which geneticists can identify traits characterized by chromosomal abnormalities from a single cell. To observe an individual’s karyotype, a geneticist first collects a person’s cells (like white blood cells) from a blood sample or other tissue. In the laboratory, the geneticist stimulates the isolated cells to begin actively dividing. The geneticist then applies the chemical colchicine to cells to arrest condensed chromosomes in metaphase. The geneticist then induces swelling in the cells using a hypotonic solution so the chromosomes spread apart. Finally, the geneticist preserves the sample in a fixative and applies it to a slide.

The geneticist then stains chromosomes with one of several dyes to better visualize each chromosome pair’s distinct and reproducible banding patterns. Following staining, the geneticist views the chromosomes using bright-field microscopy. A common stain choice is the Giemsa stain. Giemsa staining results in approximately 400–800 bands (of tightly coiled DNA and condensed proteins) arranged along all 23 chromosome pairs. An experienced geneticist can identify each band. In addition to the banding patterns, geneticists further identify chromosomes on the basis of size and centromere location. To obtain the classic depiction of the karyotype in which homologous chromosome pairs align in numerical order from longest to shortest, the geneticist obtains a digital image, identifies each chromosome, and manually arranges the chromosomes into this pattern (Figure 13.5).

At its most basic, the karyogram may reveal genetic abnormalities in which an individual has too many or too few chromosomes per cell. Examples of this are Down Syndrome, which one identifies by a third copy of chromosome 21, and Turner Syndrome, which is characterized by the presence of only one X chromosome in females instead of the normal two. Geneticists can also identify large DNA deletions or insertions. For instance, geneticists can identify Jacobsen Syndrome—which involves distinctive facial features as well as heart and bleeding defects—by a deletion on chromosome 11. Finally, the karyotype can pinpoint translocations, which occur when a segment of genetic material breaks from one chromosome and reattaches to another chromosome or to a different part of the same chromosome. Translocations are implicated in certain cancers, including chronic myelogenous leukemia.

During Mendel’s lifetime, inheritance was an abstract concept that one could only infer by performing crosses and observing the traits that offspring expressed. By observing a karyotype, today’s geneticists can actually visualize an individual’s chromosomal composition to confirm or predict genetic abnormalities in offspring, even before birth.

Chromosome Number Disorders

Of all of the chromosomal disorders, chromosome number abnormalities are the most obviously identifiable from a karyotype. Chromosome number disorders include duplicating or losing entire chromosomes, as well as changes in the number of complete sets of chromosomes. They are caused by nondisjunction, which occurs when homologous chromosome pairs or sister chromatids fail to separate during meiosis. Misaligned or incomplete synapsis, or a spindle apparatus dysfunction that facilitates chromosome migration, can cause nondisjunction. The risk of nondisjunction occurring increases with the parents’ age.

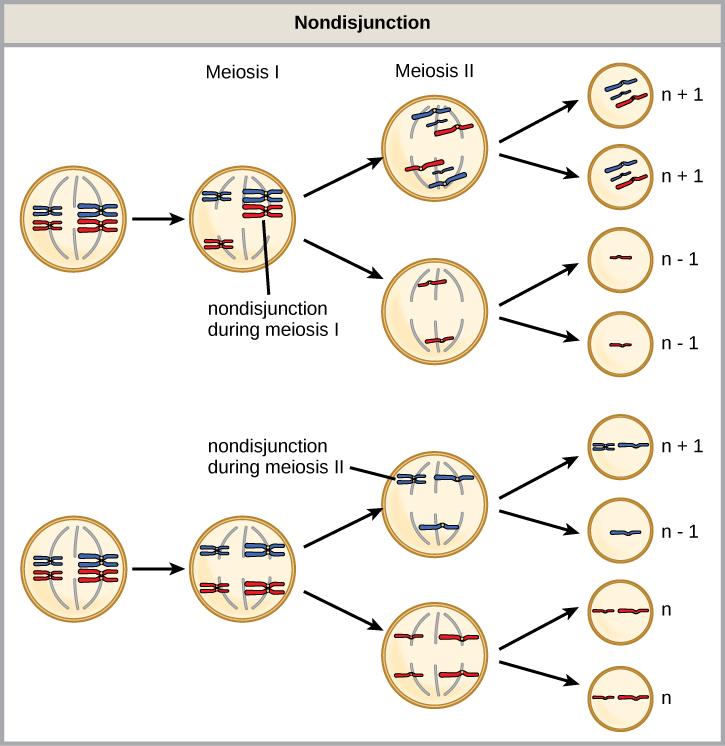

Nondisjunction can occur during either meiosis I or II, with differing results (Figure 13.6). If homologous chromosomes fail to separate during meiosis I, the result is two gametes that lack that particular chromosome and two gametes with two chromosome copies. If sister chromatids fail to separate during meiosis II, the result is one gamete that lacks that chromosome, two normal gametes with one chromosome copy, and one gamete with two chromosome copies.

Evolution Connection

- Nondisjunction only results in gametes with n+1 or n–1 chromosomes.

- Nondisjunction occurring during meiosis II results in 50 percent normal gametes.

- Nondisjunction during meiosis I results in 50 percent normal gametes.

- Nondisjunction always results in four different kinds of gametes.

Aneuploidy

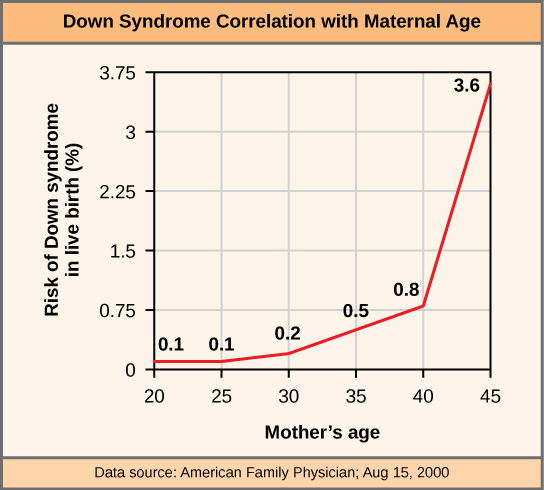

Scientists call an individual with the appropriate number of chromosomes for their species euploid. In humans, euploidy corresponds to 22 pairs of autosomes and one pair of sex chromosomes. An individual with an error in chromosome number is described as aneuploid, a term that includes monosomy (losing one chromosome) or trisomy (gaining an extraneous chromosome). Monosomic human zygotes missing any one copy of an autosome invariably fail to develop to birth because they lack essential genes. This underscores the importance of “gene dosage” in humans. Most autosomal trisomies also fail to develop to birth; however, duplications of some smaller chromosomes (13, 15, 18, 21, or 22) can result in offspring that survive for several weeks to many years. Trisomic individuals suffer from a different type of genetic imbalance: an excess in gene dose. Individuals with an extra chromosome may synthesize an abundance of the gene products, which that chromosome encodes. This extra dose (150 percent) of specific genes can lead to a number of functional challenges and often precludes development. The most common trisomy among viable births is that of chromosome 21, which corresponds to Down Syndrome. Short stature and stunted digits, facial distinctions that include a broad skull and large tongue, and significant developmental delays characterize individuals with this inherited disorder. We can correlate the incidence of Down syndrome with maternal age. Older people are more likely to become pregnant with fetuses carrying the trisomy 21 genotype (Figure 13.7).

Link to Learning

Visualize adding a chromosome that leads to Down syndrome in this video simulation (http://openstax.org/l/down_syndrome)

Polyploidy

We call an individual with more than the correct number of chromosome sets (two for diploid species) polyploid. For instance, fertilizing an abnormal diploid egg with a normal haploid sperm would yield a triploid zygote. Polyploid animals are extremely rare, with only a few examples among the flatworms, crustaceans, amphibians, fish, and lizards. Polyploid animals are sterile because meiosis cannot proceed normally and instead produces mostly aneuploid daughter cells that cannot yield viable zygotes. Rarely, polyploid animals can reproduce asexually by haplodiploidy, in which an unfertilized egg divides mitotically to produce offspring. In contrast, polyploidy is very common in the plant kingdom, and polyploid plants tend to be larger and more robust than euploids of their species (Figure 13.8).

X-Chromosome Inactivation

Humans display dramatic deleterious effects with autosomal trisomies and monosomies. Therefore, it may seem counterintuitive that human females and males can function normally, despite carrying different numbers of the X chromosome. Rather than a gain or loss of autosomes, variations in the number of sex chromosomes occur with relatively mild effects. In part, this happens because of the molecular process X inactivation. Early in development, when female mammalian embryos consist of just a few thousand cells (relative to trillions in the newborn), one X chromosome in each cell inactivates by tightly condensing into a quiescent (dormant) structure, or a Barr body. The chance that an X chromosome (maternally or paternally derived) inactivates in each cell is random, but once this occurs, all cells derived from that one will have the same inactive X chromosome or Barr body. By this process, females compensate for their double genetic dose of X chromosome. In so-called tortoiseshell cats, we observe embryonic X inactivation as color variegation (Figure 13.9). Females that are heterozygous for an X-linked coat color gene will express one of two different coat colors over different regions of their body, corresponding to whichever X chromosome inactivates in that region’s embryonic cell progenitor.

An individual carrying an abnormal number of X chromosomes will inactivate all but one X chromosome in each of her cells. However, even inactivated X chromosomes continue to express a few genes, and X chromosomes must reactivate for the proper maturation of female ovaries. As a result, X-chromosomal abnormalities typically occur with mild intellectual and physical disorders or disabilities, as well as sterility. If the X chromosome is absent altogether, the individual will not develop in utero.

Sex Chromosome Nondisjunction in Humans

Scientists have identified and characterized several errors in sex chromosome number. Individuals with three X chromosomes, triplo-X, are phenotypically female but express developmental delays and reduced fertility. The XXY genotype, corresponding to one type of Klinefelter syndrome, corresponds to phenotypically male individuals with small testes, enlarged breasts, and reduced body hair. More complex types of Klinefelter syndrome exist in which the individual has as many as five X chromosomes. In all types, every X chromosome except one undergoes inactivation to compensate for the excess genetic dosage. We see this as several Barr bodies in each cell nucleus. Turner syndrome, characterized as an X0 genotype (i.e., only a single sex chromosome), corresponds to a phenotypically female individual with short stature, webbed skin in the neck region, hearing and cardiac impairments, and sterility.

Duplications and Deletions

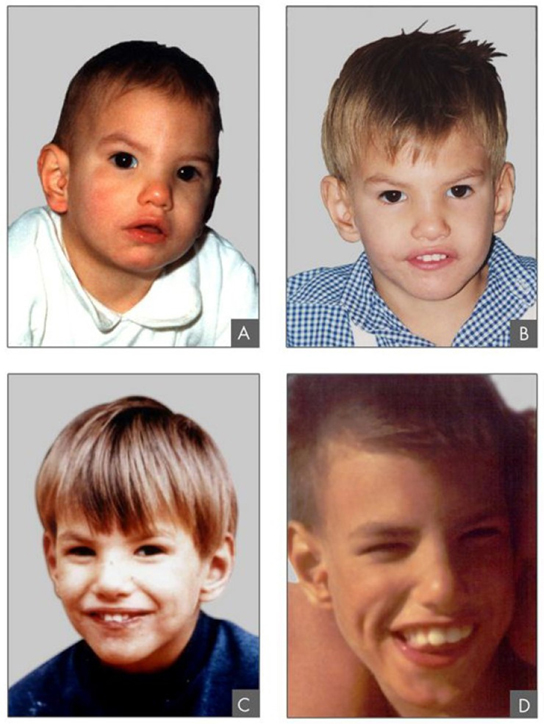

In addition to losing or gaining an entire chromosome, a chromosomal segment may duplicate or lose itself. Duplications and deletions often produce offspring that survive but exhibit abnormalities. Duplicated chromosomal segments may fuse to existing chromosomes or may be free in the nucleus. Cri-du-chat (from the French for “cry of the cat”) is a syndrome that occurs with nervous system abnormalities and identifiable physical features that result from a deletion of most 5p (the small arm of chromosome 5) (Figure 13.10). Infants with this genotype emit a characteristic high-pitched cry on which the disorder’s name is based.

Chromosomal Structural Rearrangements

Cytologists have characterized numerous structural rearrangements in chromosomes, but chromosome inversions and translocations are the most common. We can identify both during meiosis by the adaptive pairing of rearranged chromosomes with their former homologs to maintain appropriate gene alignment. If the genes on two homologs are not oriented correctly, a recombination event could result in losing genes from one chromosome and gaining genes on the other. This would produce aneuploid gametes.

Chromosome Inversions

A chromosome inversion is the detachment, 180° rotation, and reinsertion of part of a chromosome. Inversions may occur in nature as a result of mechanical shear, or from transposable elements’ action (special DNA sequences capable of facilitating rearranging chromosome segments with the help of enzymes that cut and paste DNA sequences). Unless they disrupt a gene sequence, inversions only change gene orientation and are likely to have more mild effects than aneuploid errors. However, altered gene orientation can result in functional changes because regulators of gene expression could move out of position with respect to their targets, causing aberrant levels of gene products.

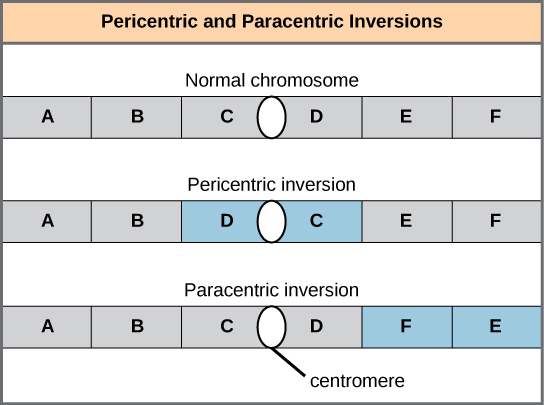

An inversion can be pericentric and include the centromere, or paracentric and occur outside the centromere (Figure 13.11). A pericentric inversion that is asymmetric about the centromere can change the chromosome arms’ relative lengths, making these inversions easily identifiable.

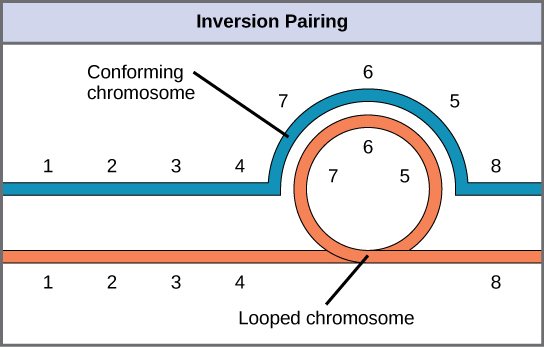

When one homologous chromosome undergoes an inversion but the other does not, the individual is an inversion heterozygote. To maintain point-for-point synapsis during meiosis, one homolog must form a loop, and the other homolog must mold around it. Although this topology can ensure that the genes correctly align, it also forces the homologs to stretch and can occur with imprecise synapsis regions (Figure 13.12).

Visual Connection

The Chromosome 18 Inversion

Not all chromosomes’ structural rearrangements produce nonviable, impaired, or infertile individuals. In rare instances, such a change can result in new species evolving. In fact, a pericentric inversion in chromosome 18 appears to have contributed to human evolution. This inversion is not present in our closest genetic relatives, the chimpanzees. Humans and chimpanzees differ cytogenetically by pericentric inversions on several chromosomes and by the fusion of two separate chromosomes in chimpanzees that correspond to chromosome two in humans.

Scientists believe the pericentric chromosome 18 inversion occurred in early humans following their divergence from a common ancestor with chimpanzees approximately five million years ago. Researchers characterizing this inversion have suggested that approximately 19,000 nucleotide bases were duplicated on 18p, and the duplicated region inverted and reinserted on chromosome 18 of an ancestral human.

A comparison of human and chimpanzee genes in the region of this inversion indicates that two genes—ROCK1 and USP14—that are adjacent on chimpanzee chromosome 17 (which corresponds to human chromosome 18) are more distantly positioned on human chromosome 18. This suggests that one of the inversion breakpoints occurred between these two genes. Interestingly, humans and chimpanzees express USP14 at distinct levels in specific cell types, including cortical cells and fibroblasts. Perhaps the chromosome 18 inversion in an ancestral human repositioned specific genes and reset their expression levels in a useful way. Because both ROCK1 and USP14 encode cellular enzymes, a change in their expression could alter cellular function. We do not know how this inversion contributed to hominid evolution, but it appears to be a significant factor in the divergence of humans from other primates.1

Translocations

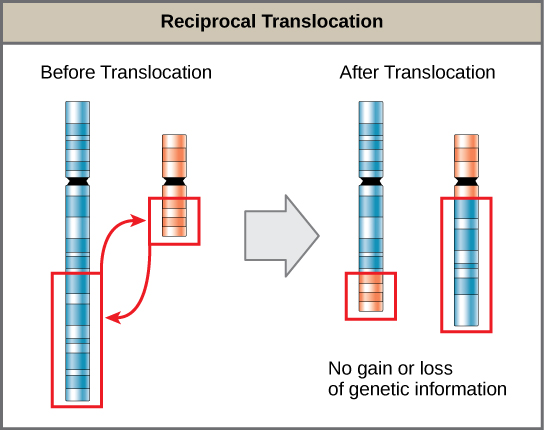

A translocation occurs when a chromosome segment dissociates and reattaches to a different, nonhomologous chromosome. Translocations can be benign or have devastating effects depending on how the positions of genes are altered with respect to regulatory sequences. Notably, specific translocations have occurred with several cancers and with schizophrenia. Reciprocal translocations result from exchanging chromosome segments between two nonhomologous chromosomes such that there is no genetic information gain or loss (Figure 13.13).

Footnotes

- 1 Violaine Goidts et al., “Segmental duplication associated with the human-specific inversion of chromosome 18: a further example of the impact of segmental duplications on karyotype and genome evolution in primates,” Human Genetics. 115 (2004):116-122