134 DNA Replication in Prokaryotes

Learning Objectives

Type your learning objectives here.

- Explain the process of DNA replication in prokaryotes

- Discuss the role of different enzymes and proteins in supporting this process

DNA replication has been well studied in prokaryotes primarily because of the small size of the genome and because of the large variety of mutants that are available. E. coli has 4.6 million base pairs in a single circular chromosome and all of it gets replicated in approximately 42 minutes, starting from a single site along the chromosome and proceeding around the circle in both directions. This means that approximately 1000 nucleotides are added per second. Thus, the process is quite rapid and occurs without many mistakes.

DNA replication employs a large number of structural proteins and enzymes, each of which plays a critical role during the process. One of the key players is the enzyme DNA polymerase, also known as DNA pol, which adds nucleotides one-by-one to the growing DNA chain that is complementary to the template strand. The addition of nucleotides requires energy; this energy is obtained from the nucleoside triphosphates ATP, GTP, TTP and CTP. Like ATP, the other NTPs (nucleoside triphosphates) are high-energy molecules that can serve both as the source of DNA nucleotides and the source of energy to drive the polymerization. When the bond between the phosphates is “broken,” the energy released is used to form the phosphodiester bond between the incoming nucleotide and the growing chain. In prokaryotes, three main types of polymerases are known: DNA pol I, DNA pol II, and DNA pol III. It is now known that DNA pol III is the enzyme required for DNA synthesis; DNA pol I is an important accessory enzyme in DNA replication, and along with DNA pol II, is primarily required for repair.

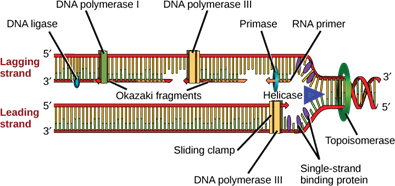

How does the replication machinery know where to begin? It turns out that there are specific nucleotide sequences called origins of replication where replication begins. In E. coli, which has a single origin of replication on its one chromosome (as do most prokaryotes), this origin of replication is approximately 245 base pairs long and is rich in AT sequences. The origin of replication is recognized by certain proteins that bind to this site. An enzyme called helicase unwinds the DNA by breaking the hydrogen bonds between the nitrogenous base pairs. ATP hydrolysis is required for this process. As the DNA opens up, Y-shaped structures called replication forks are formed. Two replication forks are formed at the origin of replication, and these get extended bi-directionally as replication proceeds. Single-strand binding proteins coat the single strands of DNA near the replication fork to prevent the single-stranded DNA from winding back into a double helix.

DNA polymerase has two important restrictions: it is able to add nucleotides only in the 5′ to 3′ direction (a new DNA strand can be only extended in this direction). It also requires a free 3′-OH group to which it can add nucleotides by forming a phosphodiester bond between the 3′-OH end and the 5′ phosphate of the next nucleotide. This essentially means that it cannot add nucleotides if a free 3′-OH group is not available. Then how does it add the first nucleotide? The problem is solved with the help of a primer that provides the free 3′-OH end. Another enzyme, RNA primase, synthesizes an RNA segment that is about five to ten nucleotides long and complementary to the template DNA. Because this sequence primes the DNA synthesis, it is appropriately called the primer. DNA polymerase can now extend this RNA primer, adding nucleotides one-by-one that are complementary to the template strand (Figure 14.14).

Link to Learning

Explore this video on DNA Polymerase in Prokaryotes and their mechanism of action (DNA Pol I, DNA Pol II and DNA Pol III).

This lecture Lac operon gene Regulation explains about the regulation of lac operon in prokaryotes including the catabolite repression of the lac operon regulated by the cyclic amp and cap protein. This lecture also explains the gene Regulation process of lac operon in the presence of glucose and lactose.

Visual Connection

Question: You isolate a cell strain in which the joining of Okazaki fragments is impaired and suspect that a mutation has occurred in an enzyme found at the replication fork. Which enzyme is most likely to be mutated?

The replication fork moves at the rate of 1000 nucleotides per second. Topoisomerase prevents the over-winding of the DNA double helix ahead of the replication fork as the DNA is opening up; it does so by causing temporary nicks in the DNA helix and then resealing it. Because DNA polymerase can only extend in the 5′ to 3′ direction, and because the DNA double helix is antiparallel, there is a slight problem at the replication fork. The two template DNA strands have opposing orientations: one strand is in the 5′ to 3′ direction, and the other is oriented in the 3′ to 5′ direction. Only one new DNA strand, the one that is complementary to the 3′ to 5′ parental DNA strand, can be synthesized continuously towards the replication fork. This continuously synthesized strand is known as the leading strand. The other strand, complementary to the 5′ to 3′ parental DNA, is extended away from the replication fork, in small fragments known as Okazaki fragments, each requiring a primer to start the synthesis. New primer segments are laid down in the direction of the replication fork, but each pointing away from it. (Okazaki fragments are named after the Japanese scientist who first discovered them. The strand with the Okazaki fragments is known as the lagging strand.)

Link to Learning

Watch this video on DNA Replication – Leading Strand vs Lagging Strand & Okazaki Fragments

The leading strand can be extended from a single primer, whereas the lagging strand needs a new primer for each of the short Okazaki fragments. The overall direction of the lagging strand will be 3′ to 5′, and that of the leading strand 5′ to 3′. A protein called the sliding clamp holds the DNA polymerase in place as it continues to add nucleotides. The sliding clamp is a ring-shaped protein that binds to the DNA and holds the polymerase in place. As synthesis proceeds, the RNA primers are replaced by DNA. The primers are removed by the exonuclease activity of DNA pol I, which uses DNA behind the RNA as its own primer and fills in the gaps left by removal of the RNA nucleotides by the addition of DNA nucleotides. The nicks that remain between the newly synthesized DNA (that replaced the RNA primer) and the previously synthesized DNA are sealed by the enzyme DNA ligase, which catalyzes the formation of phosphodiester linkages between the 3′-OH end of one nucleotide and the 5′ phosphate end of the other fragment.

Once the chromosome has been completely replicated, the two DNA copies move into two different cells during cell division. The process of DNA replication can be summarized as follows:

- DNA unwinds at the origin of replication.

- Helicase opens up the DNA-forming replication forks; these are extended bidirectionally.

- Single-strand binding proteins coat the DNA around the replication fork to prevent rewinding of the DNA.

- Topoisomerase binds at the region ahead of the replication fork to prevent supercoiling.

- Primase synthesizes RNA primers complementary to the DNA strand.

- DNA polymerase III starts adding nucleotides to the 3′-OH end of the primer.

- Elongation of both the lagging and the leading strand continues.

- RNA primers are removed by exonuclease activity.

- Gaps are filled by DNA pol I by adding dNTPs.

- The gap between the two DNA fragments is sealed by DNA ligase, which helps in the formation of phosphodiester bonds.

Table 14.1 summarizes the enzymes involved in prokaryotic DNA replication and the functions of each.

Prokaryotic DNA Replication: Enzymes and Their Function

| Enzyme/protein | Specific Function |

|---|---|

| DNA pol I | Removes RNA primer and replaces it with newly synthesized DNA |

| DNA pol III | Main enzyme that adds nucleotides in the 5′-3′ direction |

| Helicase | Opens the DNA helix by breaking hydrogen bonds between the nitrogenous bases |

| Ligase | Seals the gaps between the Okazaki fragments to create one continuous DNA strand |

| Primase | Synthesizes RNA primers needed to start replication |

| Sliding Clamp | Helps to hold the DNA polymerase in place when nucleotides are being added |

| Topoisomerase | Helps relieve the strain on DNA when unwinding by causing breaks, and then resealing the DNA |

| Single-strand binding proteins (SSB) | Binds to single-stranded DNA to prevent DNA from rewinding back. |