21 Lipids

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to do the following:

- Describe the four major types of lipids

- Explain the role of fats in storing energy

- Differentiate between saturated and unsaturated fatty acids

- Describe phospholipids and their role in cells

- Define the basic structure of a steroid and some steroid functions

Lipids include a diverse group of compounds that are largely nonpolar in nature. This is because they are hydrocarbons that include mostly nonpolar carbon–carbon or carbon–hydrogen bonds. Nonpolar molecules are hydrophobic (“water fearing”), or insoluble in water. Lipids perform many different functions in a cell. Cells store energy for long-term use in the form of fats. Lipids also provide insulation from the environment for plants and animals (Figure 3.12). For example, they help keep aquatic birds and mammals dry when forming a protective layer over fur or feathers because of their water-repellant hydrophobic nature. Lipids are also the building blocks of many hormones and are an important constituent of all cellular membranes. Lipids include fats, oils, waxes, phospholipids, and steroids.

Fats and Oils

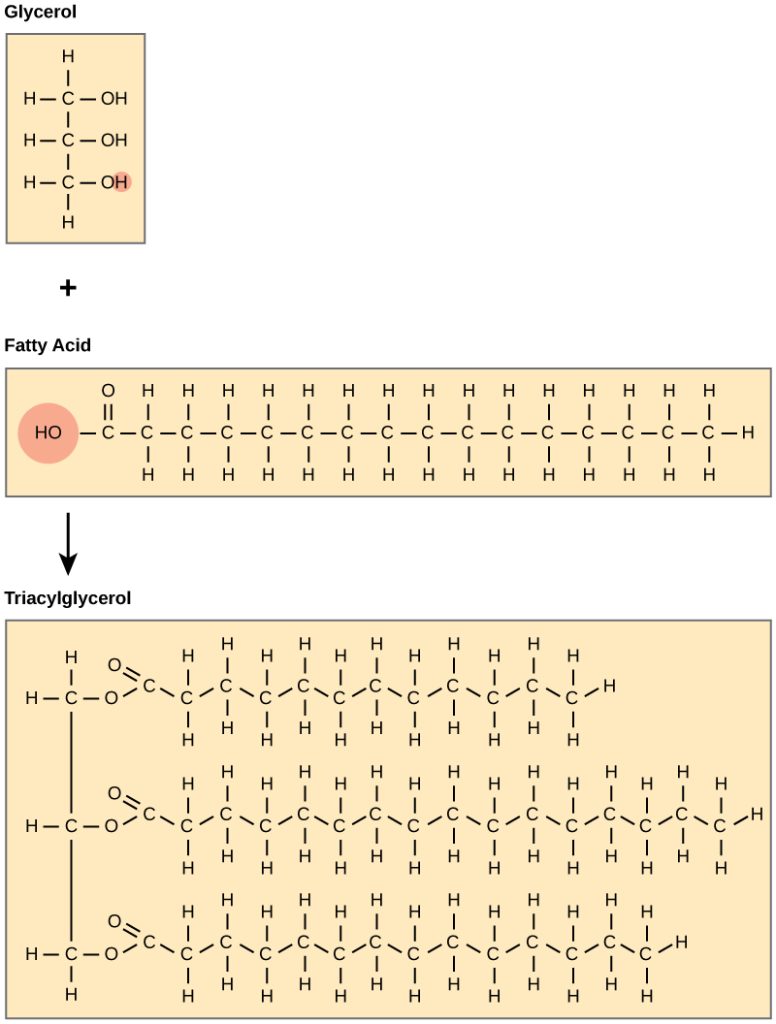

A fat molecule consists of two main components—glycerol and fatty acids. Glycerol is an organic compound (alcohol) with three carbons, five hydrogens, and three hydroxyl (OH) groups. Fatty acids have a long chain of hydrocarbons to which a carboxyl acid group (also called carboxyl group) is attached, hence the name “fatty acid.” The number of carbons in the fatty acid may range from 4 to 36. The most common are those containing 12–18 carbons. In a fat molecule, the fatty acids attach to each of the glycerol molecule’s three carbons via ester bonds (bonds of an oxygen to a carbon that is double-bonded to another oxygen) (Figure 3.13).

During this ester bond formation, three water molecules are released. The three fatty acids in the triacylglycerol may be similar or dissimilar. We also call fats triacylglycerols or triglycerides because of their chemical structure. Some fatty acids have common names that specify their origin. For example, palmitic acid, a saturated fatty acid, is derived from the palm tree. Arachidic acid is derived from Arachis hypogea, the scientific name for groundnuts or peanuts.

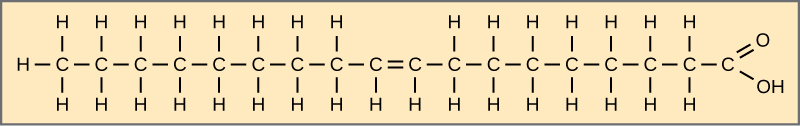

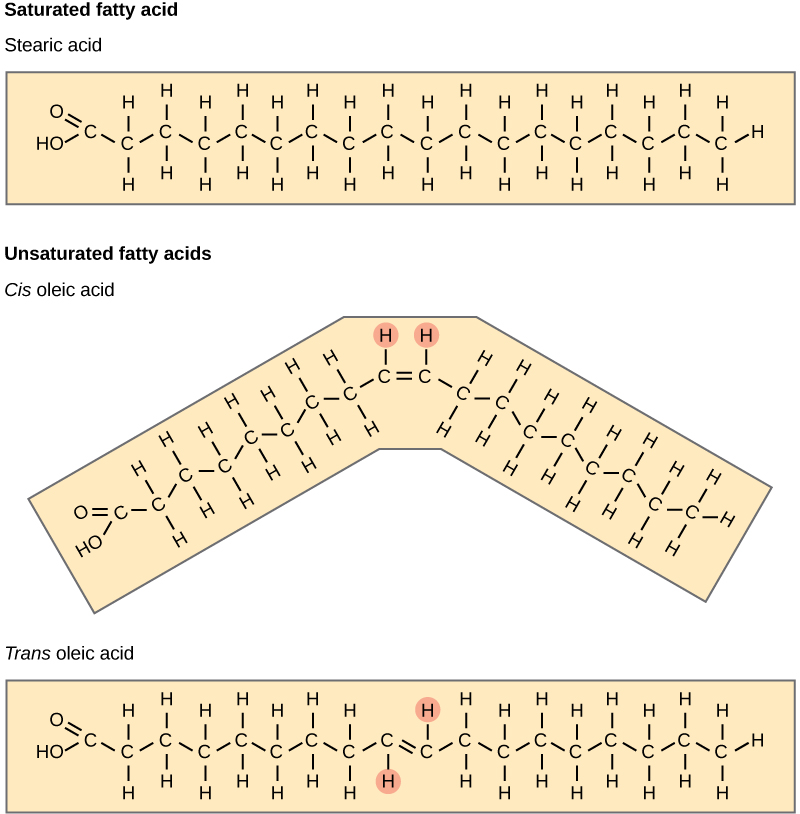

Fatty acids may be saturated or unsaturated. In a fatty acid chain, if there are only single bonds between neighboring carbons in the hydrocarbon chain, the fatty acid is saturated. Saturated fatty acids are saturated with hydrogen. In other words, the number of hydrogen atoms attached to the carbon skeleton is maximized. Stearic acid is an example of a saturated fatty acid (Figure 3.14).

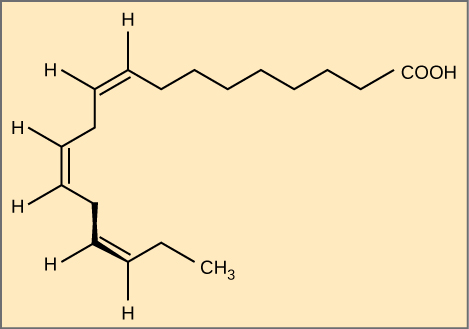

When the hydrocarbon chain contains a double bond, the fatty acid is unsaturated. Oleic acid is an example of an unsaturated fatty acid (Figure 3.15).

Most unsaturated fats are liquid at room temperature. We call these oils. If there is one double bond in the molecule, then it is a monounsaturated fat (e.g., olive oil), and if there is more than one double bond, then it is a polyunsaturated fat (e.g., canola oil).

When a fatty acid has no double bonds, it is a saturated fatty acid because it is not possible to add more hydrogen to the chain’s carbon atoms. A fat may contain similar or different fatty acids attached to glycerol. Long straight fatty acids with single bonds generally pack tightly and are solid at room temperature. Animal fats with stearic acid and palmitic acid (common in meat) and the fat with butyric acid (common in butter) are examples of saturated fats. Mammals store fats in specialized cells, or adipocytes, where fat globules occupy most of the cell’s volume. Plants store fat or oil in many seeds and use them as a source of energy during seedling development. Unsaturated fats or oils are usually of plant origin and contain cis unsaturated fatty acids. Cis and trans indicate the configuration of the molecule around the double bond. If hydrogens are present on the same side of the double bond, it is a cis fat. If the hydrogen atoms are on two different sides, it is a trans fat. The cis double bond causes a bend or a “kink” that prevents the fatty acids from packing tightly, keeping them liquid at room temperature (Figure 3.16). Olive oil, corn oil, canola oil, and cod liver oil are examples of unsaturated fats. Unsaturated fats help to lower blood cholesterol levels, whereas saturated fats contribute to plaque formation in the arteries.

Trans Fats

The food industry artificially hydrogenates oils to make them semi-solid and of a consistency desirable for many processed food products. Simply speaking, hydrogen gas is bubbled through oils to solidify them. During this hydrogenation process, double bonds of the cis– conformation in the hydrocarbon chain may convert to double bonds in the trans– conformation.

Margarine, some types of peanut butter, and shortening are examples of artificially hydrogenated trans fats. Recent studies have shown that an increase in trans fats in the human diet may lead to higher levels of low-density lipoproteins (LDL), or “bad” cholesterol, which in turn may lead to plaque deposition in the arteries, resulting in heart disease. Many fast food restaurants have recently banned using trans fats, and food labels are required to display the trans fat content.

Omega Fatty Acids

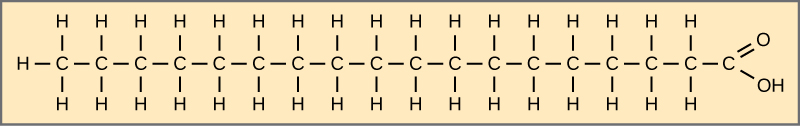

Essential fatty acids are those that the human body requires but does not synthesize. Consequently, they have to be supplemented through ingestion via the diet. Omega-3 fatty acids (like those in Figure 3.17) fall into this category and are one of only two known for humans (the other is omega-6 fatty acid). These are polyunsaturated fatty acids and are omega-3 because a double bond connects the third carbon from the hydrocarbon chain’s end to its neighboring carbon.

The farthest carbon away from the carboxyl group is numbered as the omega (ω) carbon, and if the double bond is between the third and fourth carbon from that end, it is an omega-3 fatty acid. Nutritionally important because the body does not make them, omega-3 fatty acids include alpha-linoleic acid (ALA), eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), all of which are polyunsaturated. Salmon, trout, and tuna are good sources of omega-3 fatty acids. Research indicates that omega-3 fatty acids reduce the risk of sudden death from heart attacks, lower triglycerides in the blood, decrease blood pressure, and prevent thrombosis by inhibiting blood clotting. They also reduce inflammation, and may help lower the risk of some cancers in animals.

Like carbohydrates, fats have received considerable bad publicity. It is true that eating an excess of fried foods and other “fatty” foods leads to weight gain. However, fats do have important functions. Many vitamins are fat soluble, and fats serve as a long-term storage form of fatty acids: a source of energy. They also provide insulation for the body. Therefore, we should consume “healthy” fats in moderate amounts on a regular basis.

Waxes

Wax covers some aquatic birds’ feathers and some plants’ leaf surfaces. Because of waxes’ hydrophobic nature, they prevent water from sticking on the surface (Figure 3.18). Long fatty acid chains linked to long-chain alcohols via ester bonds comprise waxes.

Phospholipids

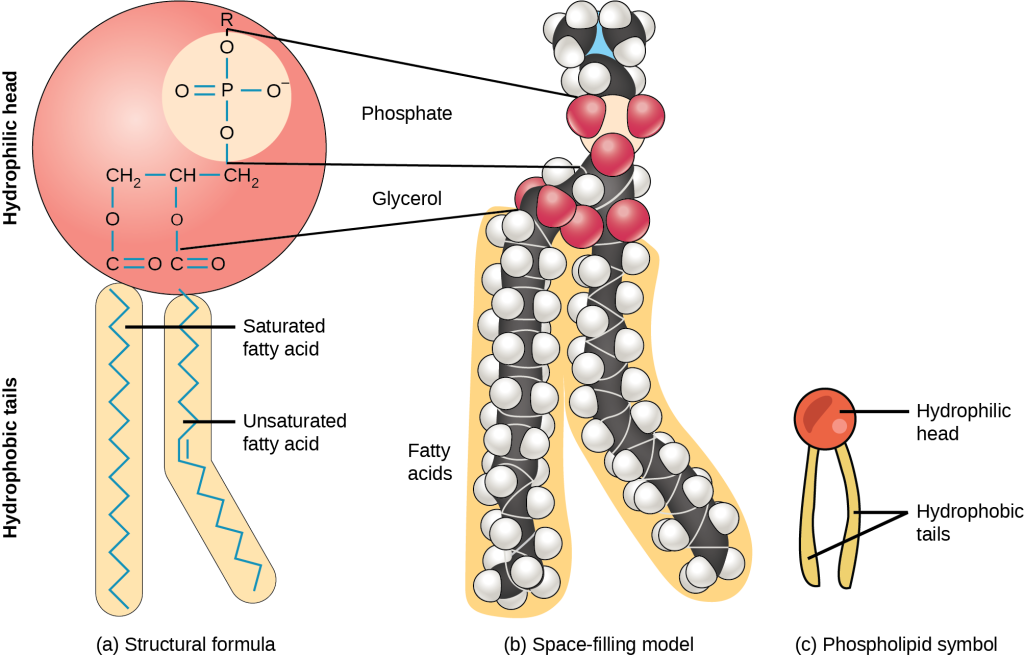

Phospholipids are major plasma membrane constituents that comprise cells’ outermost layer. Like fats, they are comprised of fatty acid chains attached to a glycerol backbone (or in some cases to another molecule called sphingosine).

However, instead of three fatty acids attached as in triglycerides, there are two fatty acids forming diacylglycerol, and a modified phosphate group occupies the glycerol backbone’s third carbon (Figure 3.19). A phosphate group alone attached to a diacylglycerol does not qualify as a phospholipid. It is phosphatidate (diacylglycerol 3-phosphate), the precursor of phospholipids. An alcohol modifies the phosphate group. Phosphatidylcholine and phosphatidylserine are two important phospholipids that are in plasma membranes.

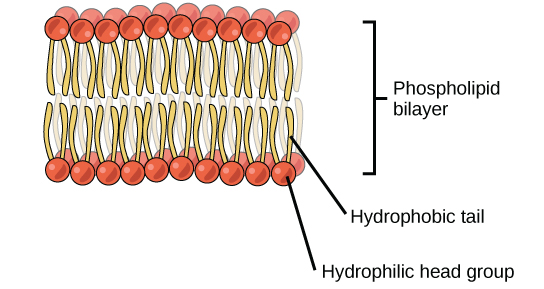

A phospholipid is an amphipathic molecule, meaning it has a hydrophobic and a hydrophilic part. The fatty acid chains are hydrophobic and cannot interact with water; whereas, the phosphate-containing group is hydrophilic and interacts with water (Figure 3.20).

The head is the hydrophilic part, and the tail contains the hydrophobic fatty acids. In a membrane, a bilayer of phospholipids forms the structure’s matrix, phospholipids’ fatty acid tails face inside, away from water, whereas the phosphate group faces the outer, aqueous side (Figure 3.20).

Phospholipids are responsible for the plasma membrane’s dynamic nature. If a drop of phospholipids is placed in water, it spontaneously forms a structure that scientists call a micelle, where the hydrophilic phosphate heads face the outside and the fatty acids face the structure’s interior.

Steroids

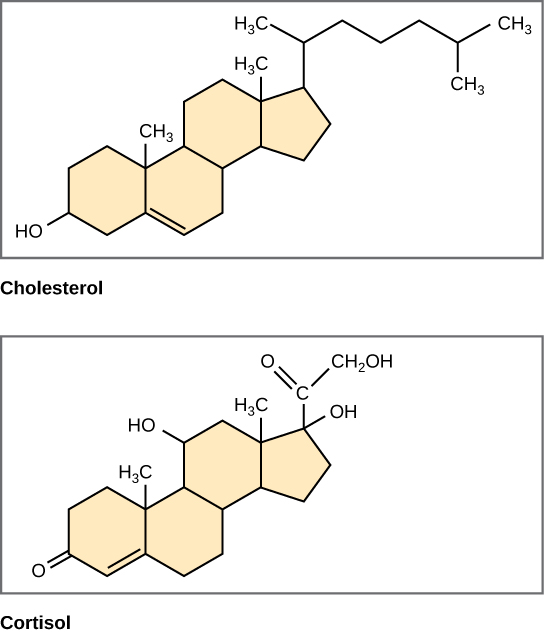

Unlike the phospholipids and fats that we discussed earlier, steroids have a fused ring structure. Although they do not resemble the other lipids, scientists group them with them because they are also hydrophobic and insoluble in water. All steroids have four linked carbon rings and several of them, like cholesterol, have a short tail (Figure 3.21). Many steroids also have the –OH functional group, which puts them in the alcohol classification (sterols).

Cholesterol is the most common steroid. The liver synthesizes cholesterol, which is the precursor to many steroid hormones such as testosterone and estradiol, which gonads and endocrine glands secrete. It is also the precursor to Vitamin D. Cholesterol is also the precursor of bile salts, which help emulsifying fats and their subsequent absorption by cells. Although lay people often speak negatively about cholesterol, it is necessary for the body’s proper functioning. Sterols (cholesterol in animal cells, phytosterol in plants) are components of the plasma membrane of cells and are found within the phospholipid bilayer.

Link to Learning

For an additional perspective on lipids, explore the interactive animation “Biomolecules: The Lipids”.