106 The Process of Meiosis

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to do the following:

- Describe the behavior of chromosomes during meiosis, and the differences between the first and second meiotic divisions

- Describe the cellular events that take place during meiosis

- Explain the differences between meiosis and mitosis

- Explain the mechanisms within the meiotic process that produce genetic variation among the haploid gametes

Sexual reproduction requires the union of two specialized cells, called gametes, each of which contains one set of chromosomes. When gametes unite, they form a zygote, or a fertilized egg that contains two sets of chromosomes. (Note: Cells that contain one set of chromosomes are called haploid; cells containing two sets of chromosomes are called diploid). If the reproductive cycle is to continue for any sexually reproducing species, then the diploid cell must somehow maintain their two sets of chromosomes and do so by reducing its number of chromosome sets to produce haploid gametes (reduction division); otherwise, the number of chromosome sets will double with every future round of fertilization.

Therefore, sexual reproduction requires a nuclear division that reduces the number of chromosome sets by half.

Link to Learning

Watch this video on Meiosis: The Reduction Division

In humans, 46 chromosomes can be found in each somatic cell (n= 23, haploid and 2n= 46, diploid). These chromosomes condense sufficiently to be seen under a compound light microscope. This makes them distinguishable from each other by size, the centromere position and the pattern of chromatin-binding stained colored bands is demonstrated as the karyotype; mitosis reveals there are two chromosomes each of 23 types, each of these pairs have the same length, centromere position and chromatin-staining pattern and are called homologous chromosomes (or homologs). These chromosome pairs carry information controlling the same or similar hereditary characters giving rise to traits. Generally, in gender determination, in human somatic cells, the two chromosomes referred to as X and Y do not follow this homologous rule; human females are chromosomally homologous (XX), while males have two sex chromosomes, the X and Y, which are non-homologous.

In summary, animals and plants and many unicellular organisms are diploid and therefore have two sets of chromosomes. In each somatic cell of the organism (all cells of a multicellular organism except the gametes or reproductive cells), the nucleus contains two copies of each chromosome, called homologous chromosomes. Homologous chromosomes are matched pairs containing the same genetic information in identical locations along their lengths. Diploid organisms inherit one copy of each homologous chromosome from each parent.

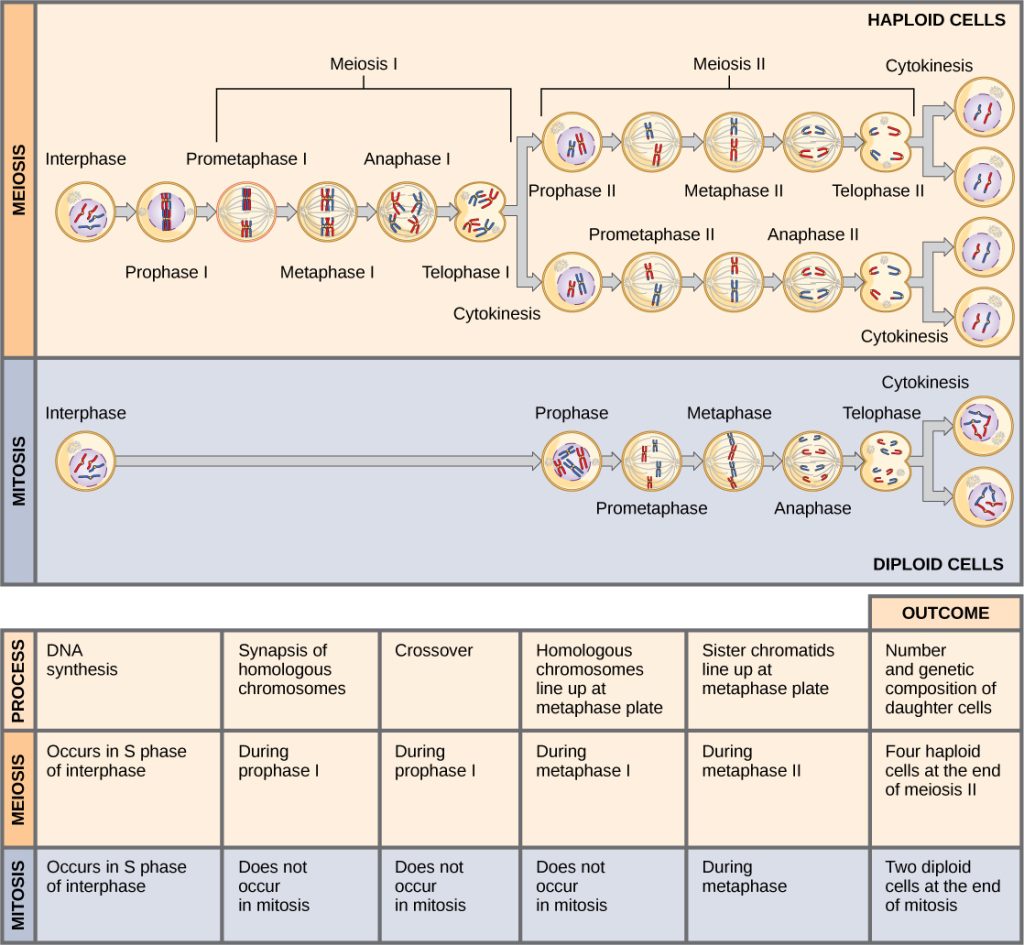

Mitosis vs. Meiosis

Meiosis is the nuclear division that forms haploid cells from diploid cells, and it employs many of the same cellular mechanisms as mitosis. However, as you have learned, mitosis produces daughter cells whose nuclei are genetically identical to the original parent nucleus. In mitosis, both the parent and the daughter nuclei are at the same “ploidy level”—diploid in the case of most multicellular animals. Plants use mitosis to grow as sporophytes and to grow and produce eggs and sperm as gametophytes, so they use mitosis for both haploid and diploid cells (as well as for all other ploidies). In meiosis, the starting nucleus is always diploid and the daughter nuclei that result are haploid. To achieve this reduction in chromosome number, meiosis consists of one round of chromosome replication followed by two rounds of nuclear division.

Genes are the units of inheritance passed on from parents to offspring. Genetic information endows offspring with their traits through its transmission, which has its molecular basis in the replication of DNA. The units of inheritance are a genetic program written in the language of specific sequences of DNA. In plants and animals, reproductive cells or gametes (male-sperms and female-eggs) are the carriers of this information and, through fusion or fertilization, pass on these units of inheritance from both parents to the offspring. Small amounts of DNA are carried in the mitochondria and chloroplasts, which are independent of the DNA of a eukaryotic cell that is contained or packaged into chromosomes within the nucleus. A gene’s location along the length of a chromosome is specified as the locus (plural loci; Latin meaning “place”). A single chromosome comprises of a single long DNA molecule, closely coiled in association with various proteins, and includes hundreds to a few thousand genes, each made up of a precise sequence of nucleotides along the DNA molecule.

Asexually reproducing organisms have genetically identical copies as offspring and are clones. Thus, amoeba or yeast cells are sole parents who transmit all their genetic information or pass copies of their entire chromosomes through mitosis cell division to their offspring without the involvement of fusion of gametes.

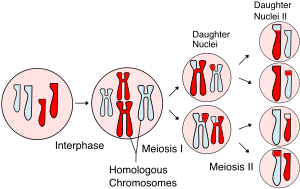

Sexually reproducing organisms are two parents who produce gametes by distinct cell division called meiosis. These gametes fuse during fertilization giving rise to offspring that have unique combinations of genes inherited from both parents. Therefore, these offspring are not clones because they genetically vary from each other and collectively present family resemblance but not exact replicas (picture below). Because the events that occur during each of the division stages are analogous to the events of mitosis, the same stage names are assigned. However, because there are two rounds of division, the major process and the stages are designated with a “I” or a “II.” Thus, meiosis I is the first round of meiotic division and consists of prophase I, prometaphase I, and so on. Likewise, Meiosis II (during which the second round of meiotic division takes place) includes prophase II, prometaphase II, and so on. The two essential parts of reproduction are fertilization and meiosis, and they alternate in sexual life cycles. In the human life cycle, for fertilization, the haploid sperm (n= 23) fuses with the haploid egg (n= 23) to form the diploid zygote (2n= 46), which divides by mitosis into the embryo, which will develop into the fetus as it attaches in the uterus and eventually be born and become sexually mature, and the meiosis process repeats again in the gonads.

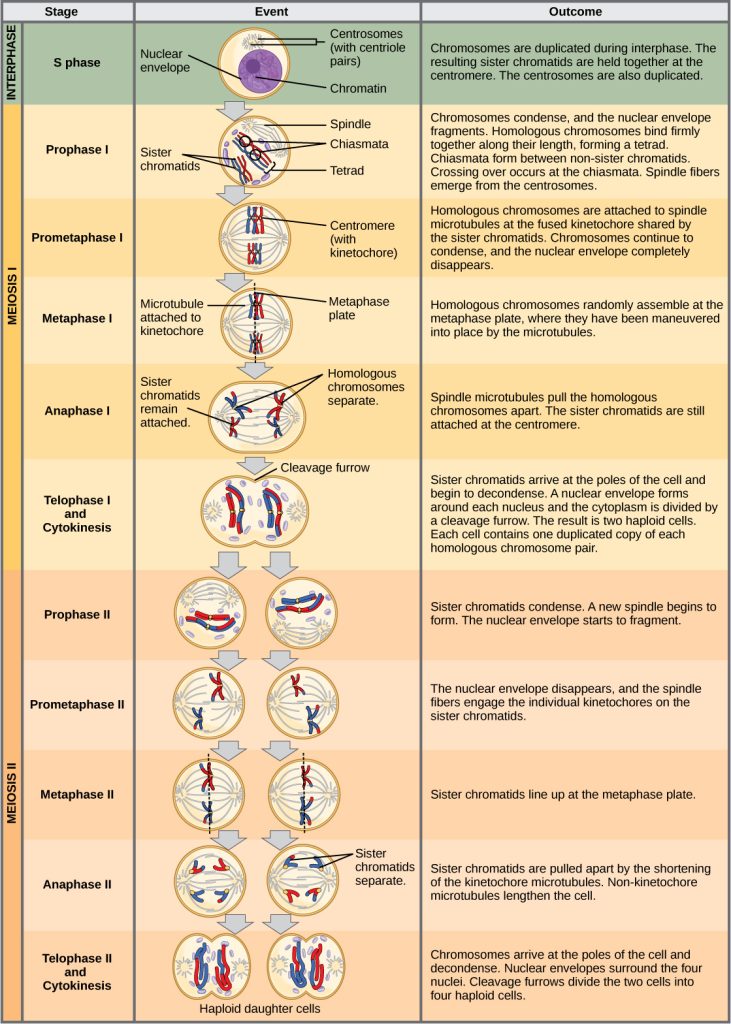

Meiosis I

Meiosis is preceded by an interphase consisting of G1, S, and G2 phases, which are nearly identical to the phases preceding mitosis. The G1 phase (the “first gap phase”) is focused on cell growth. During the S phase—the second phase of interphase—the cell copies or replicates the DNA of the chromosomes. Finally, in the G2 phase (the “second gap phase”) the cell undergoes the final preparations for meiosis.

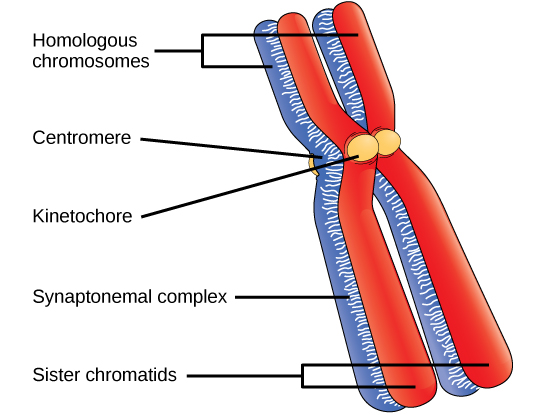

During DNA duplication in the S phase, each chromosome is replicated to produce two identical copies—sister chromatids—that are held together at the centromere by cohesin proteins, which hold the chromatids together until anaphase II.

Prophase I

Early in prophase I, before the chromosomes can be seen clearly with a microscope, the homologous chromosomes are attached at their tips to the nuclear envelope by proteins. As the nuclear envelope begins to break down, the proteins associated with homologous chromosomes bring the pair closer together. Recall that in mitosis, homologous chromosomes do not pair together. The synaptonemal complex, a lattice of proteins between the homologous chromosomes, first forms at specific locations and then spreads outward to cover the entire length of the chromosomes. The tight pairing of the homologous chromosomes is called synapsis. In synapsis, the genes on the chromatids of the homologous chromosomes are aligned precisely with each other. The synaptonemal complex supports the exchange of chromosomal segments between homologous nonsister chromatids—a process called crossing over (crossover). The crossing over can be observed visually after the exchange as chiasmata (singular = chiasma) (Figure 11.2).

In humans, even though the X and Y sex chromosomes are not completely homologous (that is, most of their genes differ), there is a small region of homology that allows the X and Y chromosomes to pair up during prophase I. A partial synaptonemal complex develops only between the regions of homology.

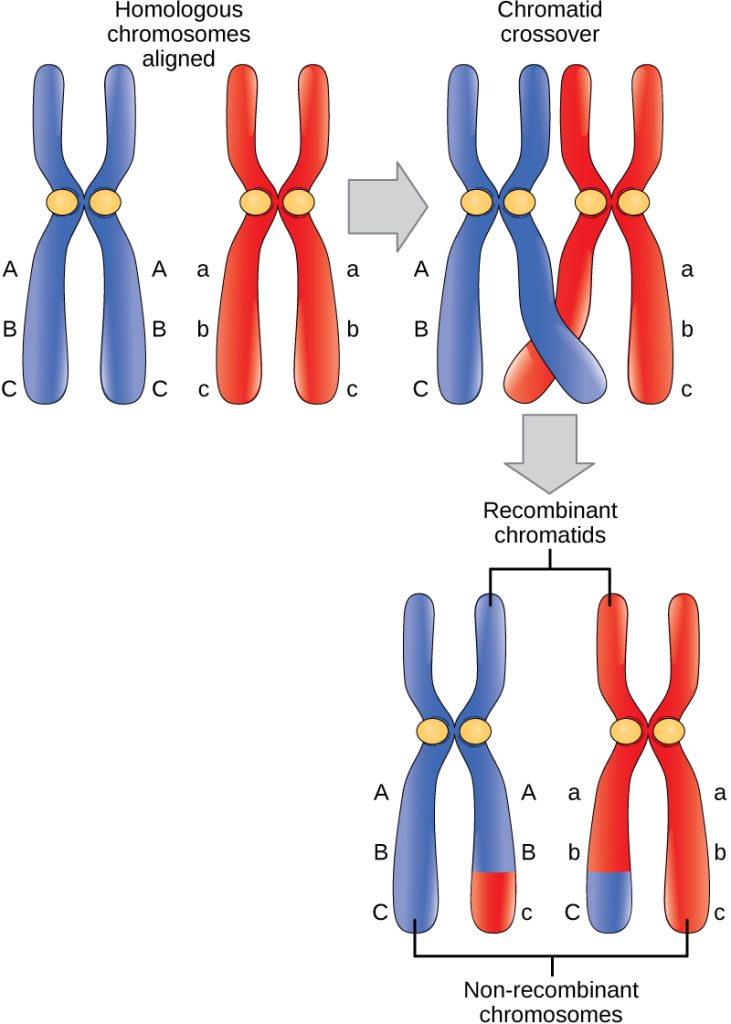

Located at intervals along the synaptonemal complex are large protein assemblies called recombination nodules. These assemblies mark the points of later chiasmata and mediate the multistep process of crossing over—or genetic recombination—between the nonsister chromatids. Near the recombination nodule, the double-stranded DNA of each chromatid is cleaved, the cut ends are modified, and a new connection is made between the nonsister chromatids. As prophase I progresses, the synaptonemal complex begins to break down and the chromosomes begin to condense. When the synaptonemal complex is gone, the homologous chromosomes remain attached to each other at the centromere and at chiasmata. The chiasmata remain until anaphase I. The number of chiasmata varies according to the species and the length of the chromosome. There must be at least one chiasma per chromosome for proper separation of homologous chromosomes during meiosis I, but there may be as many as 25. Following crossing over, the synaptonemal complex breaks down, and the cohesin connection between homologous pairs is removed. At the end of prophase I, the pairs are held together only at the chiasmata (Figure 11.3). These pairs are called tetrads because a total of four sister chromatids of each pair of homologous chromosomes are now visible.

The crossing over events are the first source of genetic variation in the nuclei produced by meiosis. A single crossing over event between homologous nonsister chromatids leads to a reciprocal exchange of equivalent DNA between an egg-derived chromosome and a sperm-derived chromosome. When a recombinant sister chromatid is moved into a gamete cell, it will carry a combination of maternal and paternal genes that did not exist before the crossing over. The crossing over events can occur almost anywhere along the length of the synapsed chromosomes. Different cells undergoing meiosis will therefore produce different recombinant chromatids, with varying combinations of maternal and parental genes. Multiple crossing overs in an arm of the chromosome have the same effect, exchanging segments of DNA to produce genetically recombined chromosomes.

Prometaphase I

The key event in prometaphase I is the attachment of the spindle fiber microtubules to the kinetochore proteins at the centromeres. Kinetochore proteins are multiprotein complexes that bind the centromeres of a chromosome to the microtubules of the mitotic spindle. Microtubules grow from microtubule-organizing centers (MTOCs). In animal cells, MTOCs are centrosomes located at opposite poles of the cell. The microtubules from each pole move toward the middle of the cell and attach to one of the kinetochores of the two fused homologous chromosomes. Each member of the homologous pair attaches to a microtubule extending from opposite poles of the cell so that in the next phase, the microtubules can pull the homologous pair apart. A spindle fiber that has attached to a kinetochore is called a kinetochore microtubule. At the end of prometaphase I, each tetrad is attached to microtubules from both poles, with one homologous chromosome facing each pole. The homologous chromosomes are still held together at the chiasmata. In addition, the nuclear membrane has broken down entirely.

Metaphase I

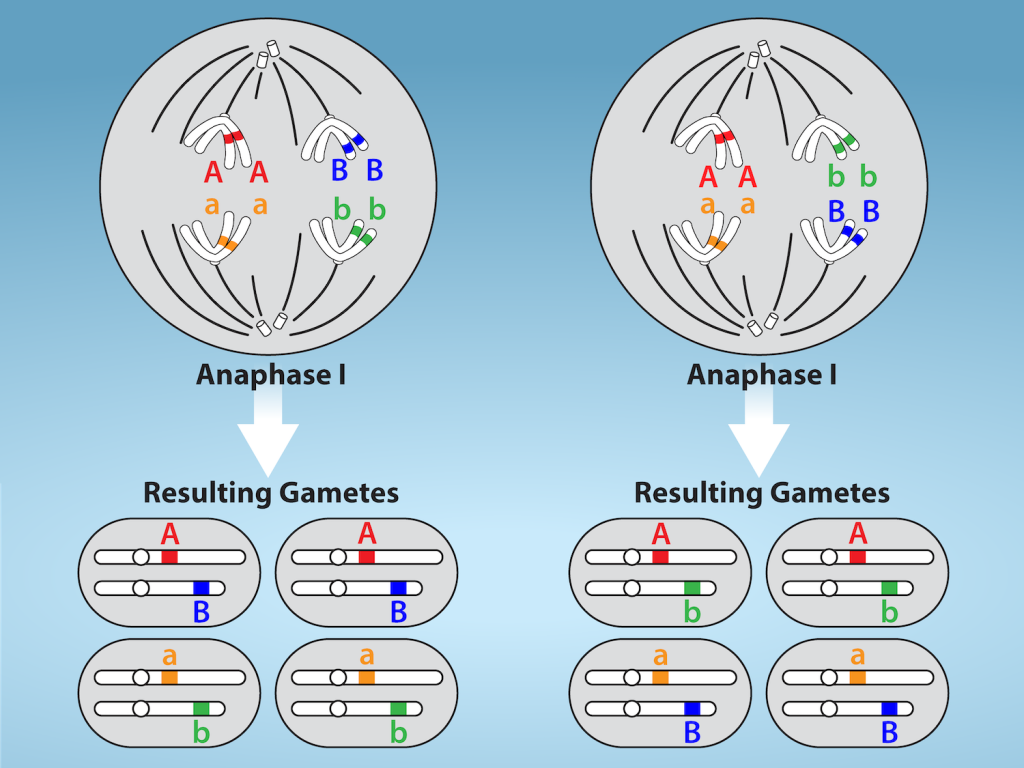

During metaphase I, the homologous chromosomes are arranged at the metaphase plate—roughly in the midline of the cell, with the kinetochores facing opposite poles. Each homologous pair is oriented randomly at the equator. For example, if the two homologous members of chromosome 1 are labeled a and b, then the chromosomes could line up a-b or b-a. This is important in determining the genes carried by a gamete, as each will only receive one of the two homologous chromosomes. (Recall that homologous chromosomes are not identical. They contain different versions of the same genes, and after recombination during crossing over, each gamete will have a unique genetic makeup that has never existed before).

The randomness in the alignment of recombined chromosomes at the metaphase plate, coupled with the crossing over events between nonsister chromatids, is responsible for much of the genetic variation in the offspring. To clarify this further, remember that the homologous chromosomes of a sexually reproducing organism are originally inherited as two separate sets, one from each parent. Using humans as an example, one set of 23 chromosomes is present in the egg cell, often called maternal chromosomes because the genetic contributor is often the mother. The other set of 23 chromosomes is contained in the sperm, and the genetic contributor is called a father, providing the paternal chromosomes. Every cell of the multicellular offspring has copies of the original two sets of homologous chromosomes. When the offspring human creates their own gametes through meiosis, the two sets of chromosomes will be rearranged. In prophase I of meiosis, the homologous chromosomes form the tetrads. In metaphase I, these pairs line up at the midway point between the two poles of the cell to form the metaphase plate. Because there is an equal chance that a microtubule fiber will encounter a maternally or paternally inherited chromosome, the arrangement of the tetrads at the metaphase plate is random. Thus, any maternally inherited chromosome may face either pole. Likewise, any paternally inherited chromosome may also face either pole. The orientation of each tetrad is independent of the orientation of the other 22 tetrads.

This event—the random (or independent) assortment of homologous chromosomes at the metaphase plate—is the second mechanism that introduces variation into the gametes or spores. In each cell that undergoes meiosis, the arrangement of the tetrads is different. The number of variations is dependent on the number of chromosomes making up a set. There are two possibilities for orientation at the metaphase plate; the possible number of alignments therefore equals 2n in a diploid cell, where n is the number of chromosomes per haploid set. Humans have 23 chromosome pairs, which results in over eight million (223) possible genetically distinct gametes just from the random alignment of chromosomes at the metaphase plate. This number does not include the variability that was previously produced by crossing over between the nonsister chromatids. Given these two mechanisms, it is highly unlikely that any two haploid cells resulting from meiosis will have the same genetic composition (Figure 11.4).

To summarize, meiosis I creates genetically diverse gametes in two ways. First, during prophase I, crossing over events between the nonsister chromatids of each homologous pair of chromosomes generate recombinant chromatids with new combinations of maternal and paternal genes. Second, the random assortment of tetrads on the metaphase plate produces unique combinations of maternal and paternal chromosomes that will make their way into the gametes.

Anaphase I

In anaphase I, the microtubules pull the linked chromosomes apart. The sister chromatids remain tightly bound together at the centromere. The chiasmata are broken in anaphase I as the microtubules attached to the fused kinetochores pull the homologous chromosomes apart (Figure 11.4)

Telophase I and Cytokinesis

In telophase, the separated chromosomes arrive at opposite poles. The remainder of the typical telophase events may or may not occur, depending on the species. In some organisms, the chromosomes “decondense” and nuclear envelopes form around the separated sets of chromatids produced during telophase I. In other organisms, cytokinesis—the physical separation of the cytoplasmic components into two daughter cells—occurs without reformation of the nuclei. In nearly all species of animals and some fungi, cytokinesis separates the cell contents via a cleavage furrow (constriction of the actin ring that leads to cytoplasmic division). In plants, a cell plate is formed during cell cytokinesis by Golgi vesicles fusing at the metaphase plate. This cell plate will ultimately lead to the formation of cell walls that separate the two daughter cells.

Two haploid cells are the result of the first meiotic division of a diploid cell. The cells are haploid because at each pole, there is just one of each pair of the homologous chromosomes. Therefore, only one full set of the chromosomes is present. This is why the cells are considered haploid—there is only one chromosome set, even though each chromosome still consists of two sister chromatids. Recall that sister chromatids are merely duplicates of one of the two homologous chromosomes (except for changes that occurred during crossing over). In meiosis II, these two sister chromatids will separate, creating four haploid daughter cells.

Link to Learning

Review the process of meiosis, observing how chromosomes align and migrate, at Meiosis: An Interactive Animation.

Meiosis II

In some species, cells enter a brief interphase, or interkinesis, before entering meiosis II. Interkinesis lacks an S phase, so chromosomes are not duplicated. The two cells produced in meiosis I go through the events of meiosis II in synchrony. During meiosis II, the sister chromatids within the two daughter cells separate, forming four new haploid gametes. The mechanics of meiosis II are similar to mitosis, except that each dividing cell has only one set of homologous chromosomes, each with two chromatids. Therefore, each cell has half the number of sister chromatids to separate out as a diploid cell undergoing mitosis. In terms of chromosomal content, cells at the start of meiosis II are similar to haploid cells in G2, preparing to undergo mitosis.

Prophase II

If the chromosomes decondensed in telophase I, they condense again. If nuclear envelopes were formed, they fragment into vesicles. The MTOCs that were duplicated during interkinesis move away from each other toward opposite poles, and new spindles are formed.

Prometaphase II

The nuclear envelopes are completely broken down, and the spindle is fully formed. Each sister chromatid forms an individual kinetochore that attaches to microtubules from opposite poles.

Metaphase II

The sister chromatids are maximally condensed and aligned at the equator of the cell.

Anaphase II

The sister chromatids are pulled apart by the kinetochore microtubules and move toward opposite poles. Nonkinetochore microtubules elongate the cell.

The chromosomes arrive at opposite poles and begin to decondense. Nuclear envelopes form around the chromosomes. If the parent cell was diploid, as is most commonly the case, then cytokinesis now separates the two cells into four unique haploid cells. The cells produced are genetically unique because of the random assortment of paternal and maternal homologs and because of the recombination of maternal and paternal segments of chromosomes (with their sets of genes) that occurs during crossover. Thus, the four daughter cells after meiosis I and II are genetically distinct from one another and the parent cell, which means they are not clones. The entire process of meiosis is outlined in Figure 11.6.

Comparing Meiosis and Mitosis

Mitosis and meiosis are both forms of division of the nucleus in eukaryotic cells. They share some similarities, but also exhibit a number of distinct processes that lead to very different outcomes (Figure 11.7). Mitosis is a single nuclear division that results in two nuclei that are usually partitioned into two new cells. The nuclei resulting from a mitotic division are genetically identical to the original nucleus. They have the same number of sets of chromosomes: one set in the case of haploid cells and two sets in the case of diploid cells. In contrast, meiosis consists of two nuclear divisions resulting in four nuclei that are usually partitioned into four new, genetically distinct cells. The four nuclei produced during meiosis are not genetically identical, and they contain one chromosome set only. This is half the number of chromosome sets of the original cell, which is diploid.

The main differences between mitosis and meiosis occur in meiosis I, which is a very different nuclear division than mitosis. In meiosis I, the homologous chromosome pairs physically meet and are bound together with the synaptonemal complex. Following this, the chromosomes develop chiasmata and undergo crossover between nonsister chromatids. In the end, the chromosomes line up along the metaphase plate as tetrads—with kinetochore fibers from opposite spindle poles attached to each kinetochore of a homolog to form a tetrad. All of these events occur only in meiosis I.

When the chiasmata resolve and the tetrad is broken up with the homologous chromosomes moving to one pole or another, the ploidy level—the number of sets of chromosomes in each future nucleus—has been reduced from two to one. For this reason, meiosis I is referred to as a reductional division. There is no such reduction in ploidy level during mitosis.

Meiosis II is analogous to a mitotic division. In this case, the duplicated chromosomes (only one set of them) line up on the metaphase plate with divided kinetochores attached to kinetochore fibers from opposite poles. During anaphase II, as in mitotic anaphase, the kinetochores divide and one sister chromatid—now referred to as a chromosome—is pulled to one pole while the other sister chromatid is pulled to the other pole. If it were not for the fact that there had been crossover, the two products of each individual meiosis II division would be identical (as in mitosis). Instead, they are different because there has always been at least one crossover per chromosome. Meiosis II is not a reduction division because although there are fewer copies of the genome in the resulting cells, there is still one set of chromosomes, as there was at the end of meiosis I.

Evolution Connection

The Mystery of the Evolution of Meiosis

Some characteristics of organisms are so widespread and fundamental that it is sometimes difficult to remember that they evolved like other simple traits. Meiosis is such an extraordinarily complex series of cellular events that biologists have had trouble testing hypotheses concerning how it may have evolved. Although meiosis is inextricably entwined with sexual reproduction and its advantages and disadvantages, it is important to separate the questions of the evolution of meiosis and the evolution of sex because early meiosis may have been advantageous for different reasons than it is now. Thinking outside the box and imagining what the early benefits of meiosis might have been is one approach to uncovering how it may have evolved.

Meiosis and mitosis share obvious cellular processes, and it makes sense that meiosis evolved from mitosis. The difficulty lies in the clear differences between meiosis I and mitosis. Adam Wilkins and Robin Holliday1 summarized the unique events that needed to occur for the evolution of meiosis from mitosis. These steps are homologous chromosome pairing and synapsis, crossover exchanges, sister chromatids remaining attached during anaphase, and suppression of DNA replication in interphase. They argue that the first step is the hardest and most important and that understanding how it evolved would make the evolutionary process clearer. They suggest genetic experiments that might shed light on the evolution of synapsis.

There are other approaches to understanding the evolution of meiosis in progress. Different forms of meiosis exist in single-celled protists. Some appear to be simpler or more “primitive” forms of meiosis. Comparing the meiotic divisions of different protists may shed light on the evolution of meiosis. Marilee Ramesh and colleagues2 compared the genes involved in meiosis in protists to understand when and where meiosis might have evolved. Although research is still ongoing, recent scholarship into meiosis in protists suggests that some aspects of meiosis may have evolved later than others. This kind of genetic comparison can tell us what aspects of meiosis are the oldest and what cellular processes they may have borrowed from in earlier cells.

Link to Learning

Click through the steps of this interactive animation to compare the meiotic process of cell division to that of mitosis: How Cells Divide.

Footnotes

- 1 Adam S. Wilkins and Robin Holliday, “The Evolution of Meiosis from Mitosis,” Genetics 181 (2009): 3–12.

- 2 Marilee A. Ramesh, Shehre-Banoo Malik and John M. Logsdon, Jr, “A Phylogenetic Inventory of Meiotic Genes: Evidence for Sex in Giardia and an Early Eukaryotic Origin of Meiosis,” Current Biology 15 (2005):185–91.